Have we gone too far myth busting criminal justice reform? Drug policy is still important

We didn't get mass incarceration from War on Drugs alone, but drugs play an important role in less discussed stages of criminal justice systems

by Bernadette Rabuy, May 23, 2016

In large part due to the wide success of Michelle Alexander’s game changing book, The New Jim Crow, the War on Drugs is often seen as the cause of mass incarceration. But as support for criminal justice reform has grown, discussions of mass incarceration have gotten more sophisticated. The sheer scale of our system of mass incarceration has caused more authors, organizations, presidential candidates, policymakers, and reporters to ask hard questions about how we got here and how we can turn the tide on mass incarceration.

The truth is our country didn’t get mass incarceration from the War on Drugs alone, but too often, when those interested in criminal justice reform are reminded of this, the argument goes to extremes and ends up understating the role of drugs in mass incarceration. Here are just some reasons that drug policy reforms matter:

-

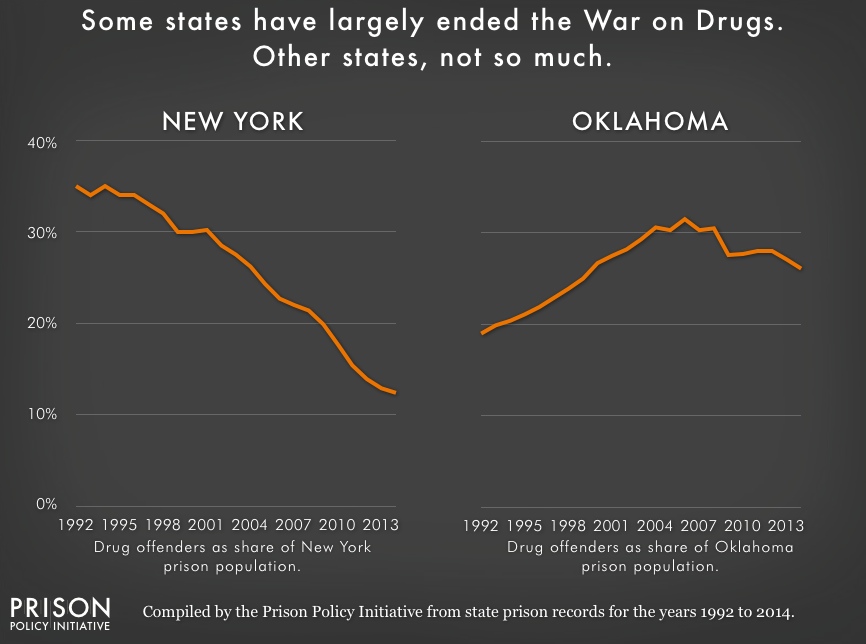

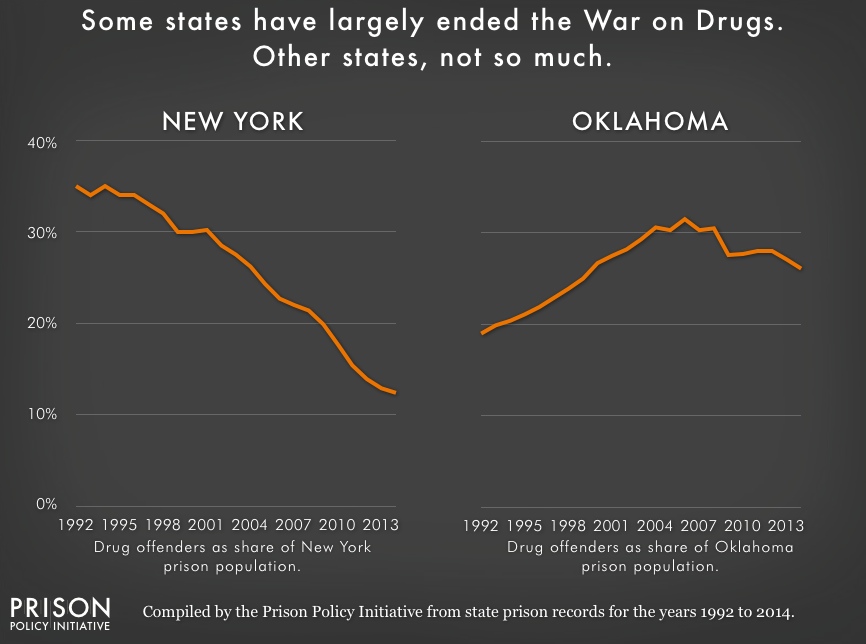

As we showed in our pie chart report, some states like New York have made huge dents in their prison population in part by focusing on drug policy reforms. New York cut its prison population by 26% from 1999-2012 in part by shifting police resources away from felony drug arrests and increasing the proportion of people with felony drug arrests who receive treatment rather than prison. So while states like New York must now look beyond drug policy reform, other states like Oklahoma or Alabama can make immediate progress by reducing admissions or length of stay for drug offenses.

For example, according to the Urban Institute, if Oklahoma halved drug admissions, it would see a 9% drop in its prison population by December 2021. The same reform would only reduce New York’s prison population by 1% in the same timeframe.

For example, according to the Urban Institute, if Oklahoma halved drug admissions, it would see a 9% drop in its prison population by December 2021. The same reform would only reduce New York’s prison population by 1% in the same timeframe.

-

While less than 16% of people in state prisons are incarcerated for a drug offense, drugs are a larger slice of the local jail and federal prison slices of the imprisonment pie and play a greater role in other less discussed stages of criminal justice systems:

Stage of criminal justice system Proportion that is drugs State Felony Prosecutions, 2009 32.6% Parole, 2014 31% State Felony Convictions, 2009 28.8% Probation, 2014 25% Local Jail Incarceration, 2002 24.7% Listed in order of highest proportion to lowest proportion. Sources: State felony prosecutions (Table 1, Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties), Parole (Table 6, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2014), State felony convictions (Table 22, Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties), Probation (Table 4, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2014), and Local jail incarceration (Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002 or see Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie for more details)

The decision to prosecute drug offenses not only means that we are sending people to relatively short stints of prison time instead of providing longer-term solutions to addiction like drug treatment, but also that we are giving people life-long criminal records that can prevent future employment, exclude them from public housing, and lead to harsher punishments for future crimes. Drug charges — and their frequent mandatory minimum sentencing — also give prosecutors leverage to compel guilty pleas on other offenses that possibly wouldn’t have resulted in a conviction otherwise.

-

A recent White House report suggests that the War on Drugs led law enforcement to focus more on drug enforcement than property and violent crimes, even when property and violent crime rates were rising from the mid 80s to the early 90s. Drug arrests peaked at 1.6 million arrests in 2006, despite the fact that drug use among Americans of all age groups had been dropping or unchanged for years.(*) Even though drug arrests are declining, our pie chart report found that there are still over 1 million drug arrests each year, most of which are for possession, not sales. Further, the greatest proportion of drug arrests nationwide is for possession of the drug the public overwhelmingly sees as the least dangerous: marijuana (39.7% of all drug arrests).

-

Drug offenses are a driver of deportation of immigrants. Between 2007 and 2012, drug convictions constituted one out of every four removals of non-citizens with a criminal conviction.

-

There are collateral consequences — specific to drug offenses — that make it extremely difficult for people convicted of drug offenses to succeed in the future. For example, some states automatically suspend a person’s driver’s license if he is convicted of a drug offense, regardless of whether a vehicle was involved. A handful of states still deny food stamps to people with drug convictions, and students can lose federal student aid if they are convicted of a drug offense.

-

Just like there are collateral consequences that are specific to drug offenses, there were overly harsh policies enacted as part of the War on Drugs that continue to do harm. One example is in California where there is a three-year sentence enhancement for prior drug convictions, a law that led at least one woman arrested for a $5 sale of cocaine to spend six years locked up. (Fortunately, there is a bill right now, SB 966, that might finally end this ineffective law.)

The six factors above concentrate on harmful effects of the War on Drugs that are easy to measure. Other effects defy easy measurement but may be as important if not more so. For example, without the War on Drugs, would police have been as likely to search people of color during traffic and street stops? And how does it change a community’s long-term relationship with the police when so much of their interaction with the police is being on the receiving end of searches? In my view, a large reason why Michelle Alexander’s drug-war-heavy explanation of the rise of mass incarceration resonated with so many readers is because it matched their personal, lived experience.

To be sure, ending mass incarceration will require rolling back the punitive laws that affect people convicted of violent offenses. But I don’t think our work is done when it comes to drug policy reform. At a time when more people such as President Obama are willing to publicly accept the view that addiction is a public health issue rather than a criminal one, there is still room for drug reforms in the movement for criminal justice reform.

Notes:

(*) For drug use from 2002 to 2014 broken down by age group (12 or older, 12 to 17, 18 to 25, and 26 or older), see Figure 2 from Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. For drug use from 1991 to 2014 for youth in grades 8, 10, and 12 see Table 2 (page 56) from 2014 Overview: Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use.