Visualizing the unequal treatment of LGBTQ people in the criminal justice system

LGBTQ people are overrepresented at every stage of our criminal justice system, from juvenile justice to parole.

by Alexi Jones, March 2, 2021

The data is clear: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ 1) people are overrepresented at every stage of criminal justice system, starting with juvenile justice system involvement. They are arrested, incarcerated, and subjected to community supervision at significantly higher rates than straight and cisgender people. This is especially true for trans people and queer women. And while incarcerated, LGBTQ individuals are subject to particularly inhumane conditions and treatment.

For this briefing, we’ve compiled the existing research on LGBTQ involvement and experiences with the criminal justice system, and – where the data did not yet exist – analyzed a recent national data set to fill in the gaps. (Namely, we provide the only national estimates for lesbian, gay, or bisexual arrest rates and community supervision rates that we know of.) We present the findings for each stage of the criminal justice system with available data, and pair them with new graphics illustrating the dramatic disparities in the system related to sexuality and gender identity.

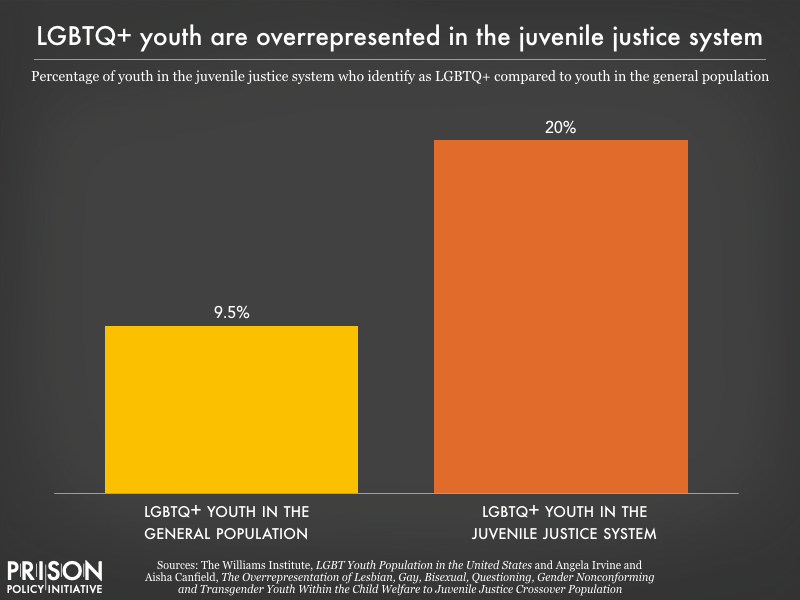

LGBTQ+ youth in the juvenile justice system

For LGBTQ people, criminal justice involvement often starts at a young age. LGBTQ youth are extremely overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. Researchers estimate that 20% of youth in the juvenile justice system are lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming, or transgender compared with 4-6% of youth in the general population. The same research shows that 40% of girls (who were assigned female at birth) in the juvenile justice system identify as LBQ and/or gender nonconforming. 2 This overrepresentation is largely due to the obstacles that LGBTQ youth face after fleeing abuse and lack of acceptance at home because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. In order to survive, LGBTQ youth are pushed towards criminalized behaviors such as drug sales, theft, or survival sex, which increase their risk of arrest and confinement.

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the criminal justice system

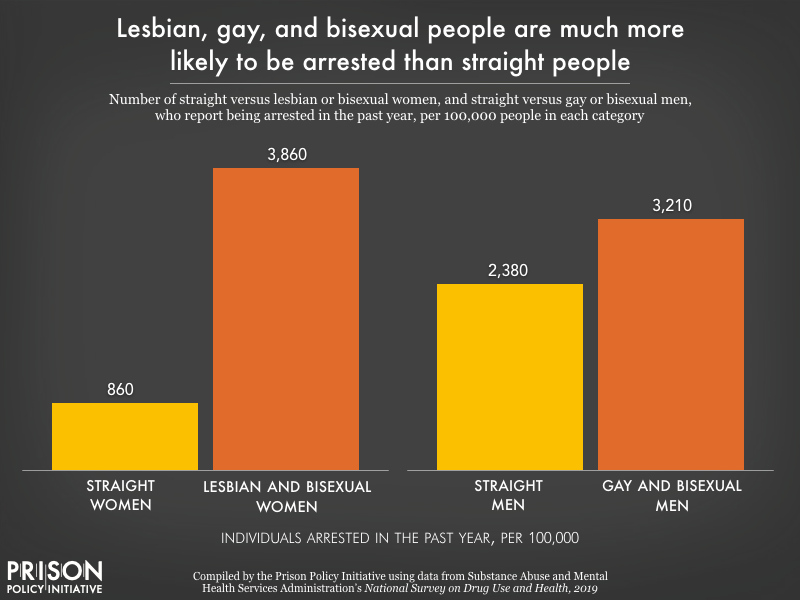

Arrest

High rates of criminal justice system contact continue into adulthood. Our analysis of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reveals that in 2019, gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals (with an arrest rate of 3,620 per 100,000) were 2.25 times as likely to be arrested in the past twelve months than straight individuals (with an arrest rate of 1,610 per 100,000). This disparity is driven by lesbian and bisexual women, who are 4 times as likely to be arrested than straight women (with an arrest rate of 3,860 per 100,000 compared to 860 per 100,000). Meanwhile, gay and bisexual men are 1.35 times as likely to be arrested than straight men (with a rate of 3,210 arrested per 100,000 compared to 2,380 per 100,000): 3

Sentencing and incarceration

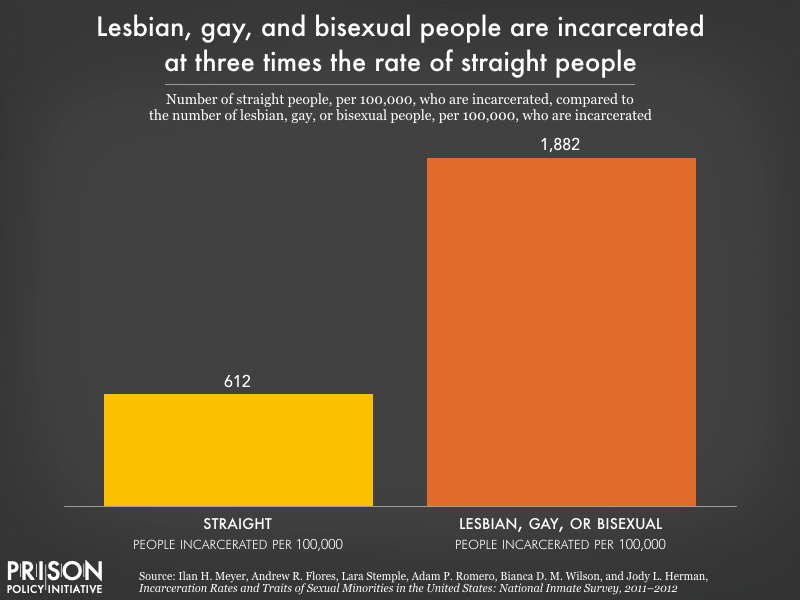

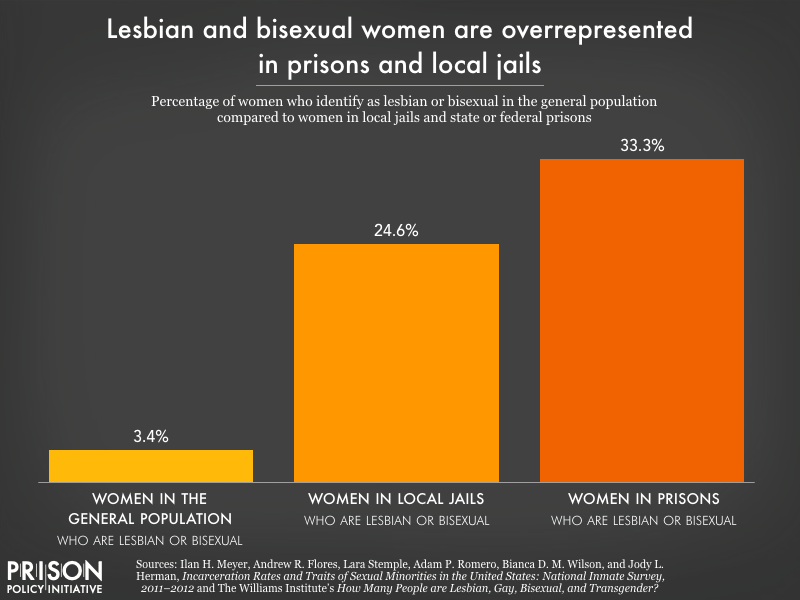

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people are also overrepresented in prisons and jails, especially lesbian and bisexual women. Researchers analyzing the most recent National Inmate Survey found that LGB people are incarcerated at a rate over three times that of the total adult population: 1,882 per 100,000 lesbian, gay, and bisexual people are incarcerated, compared with 612 per 100,000 U.S. residents aged 18 and older. This disparity, again, is largely driven by queer women, as evidenced by the researchers’ breakdown of the data by sex. Compared to the general population, in which 3.6% of men and 3.4% of women identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual:

- 1 in 20 (5.5%) men in prison identify as gay or bisexual and an additional 3.8% report having had sex with men before arrival at the facility but do not self-identify as gay or bisexual. 4

- 1 in 3 (33.3%) women in prison identify as lesbian or bisexual and another 8.8% report having sex with women, but do not identify as lesbian or bisexual.

- And almost 1 in 4 (24.6%) women in county and municipal jails identify as lesbian or bisexual, with another 9.3% who report having sex with women, but do not identify as lesbian or bisexual.

The high rates of gay, lesbian, and bisexual people behind bars can in part be attributed to the longer sentences courts impose on them. The same study of the National Inmate Survey data found that in both prisons and jails, lesbian or bisexual women were sentenced to longer periods of incarceration than straight women. And gay and bisexual men were more likely than straight men to have sentences longer than 10 years in prison.

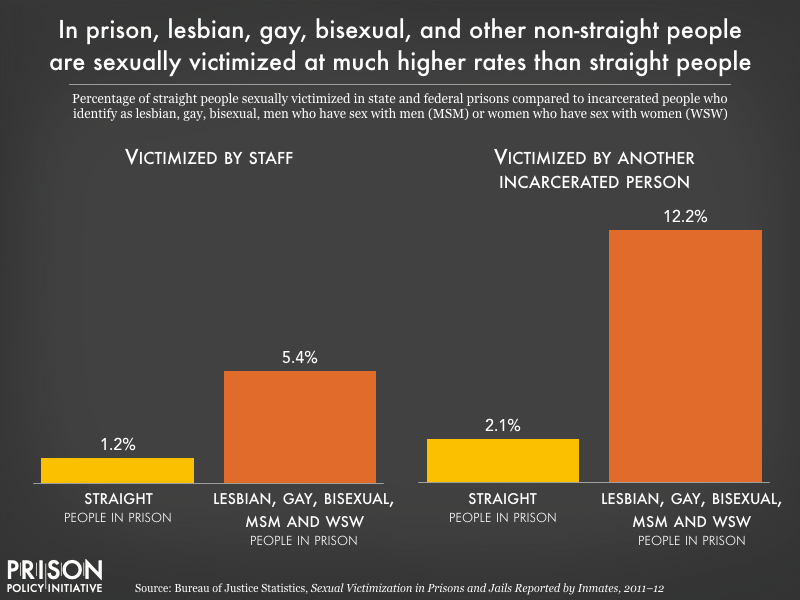

While locked up, gay, lesbian, and bisexual people are subjected to especially inhumane treatment. The National Inmate Survey study showed these “sexual minorities” were more likely to be put in solitary confinement than straight men and women in prisons and jails. In Black and Pink’s survey of 1,118 LGBTQ incarcerated people, a staggering 85% of respondents reported that they had been held in solitary confinement at some point during their sentence. And BIPOC LGBTQ incarcerated people were twice as likely to put in solitary compared to white LGBTQ incarcerated people. This is often done in the name of “protecting” queer individuals behind bars, despite the well documented, long-lasting harms of solitary confinement. And according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, LGB men and women, as well as men who have sex with men (MSM) and women who have sex with women (WSW), are also 10 times as likely to be sexually victimized by another incarcerated person and 2.6 times as likely to be victimized by staff as heterosexual incarcerated people:

Probation and parole

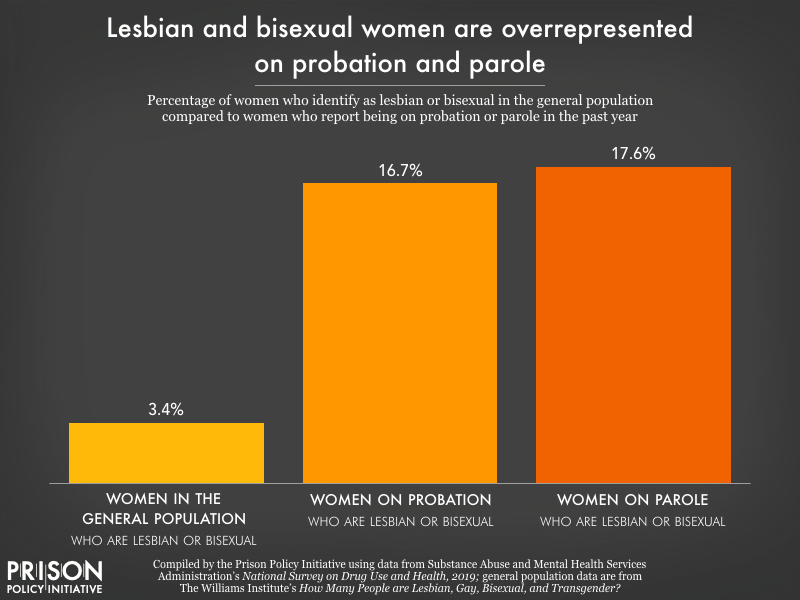

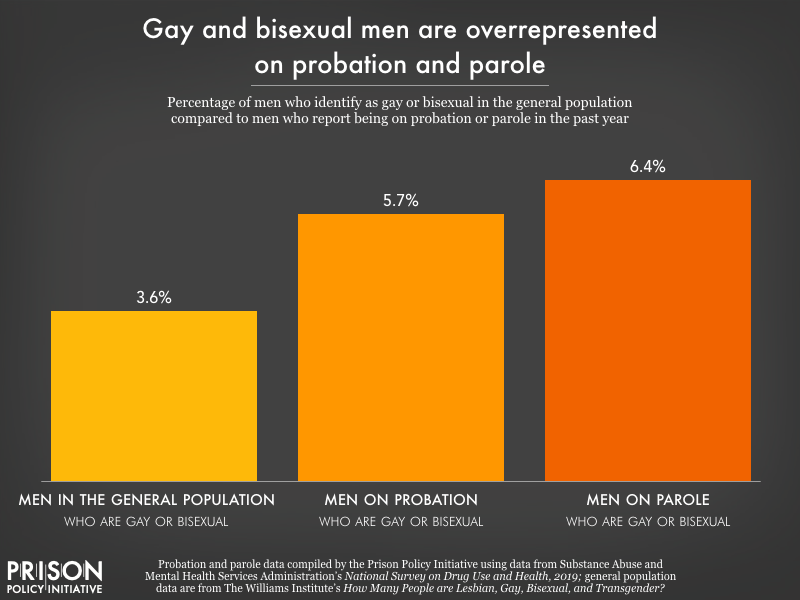

Finally, gay, lesbian, and bisexual people are overrepresented in the community supervision population. Our analysis of the NSDUH data reveals that people on probation and parole are almost twice as likely to be lesbian, gay, or bisexual than people not on probation and parole – and again, lesbian and bisexual women are especially overrepresented:

- Men on probation are somewhat more likely to be gay or bisexual (5.7%) as men not on probation (4.1%).

- Women on probation are nearly three times as likely to be lesbian or bisexual (16.7%) as women not on probation (6.3%).

- Men on parole are nearly twice as likely to be gay or bisexual (7.9%) as men not on parole (4.1%).

- And women on parole are nearly three times as likely to be lesbian or bisexual (17.6%) as women not on parole (6.4%).

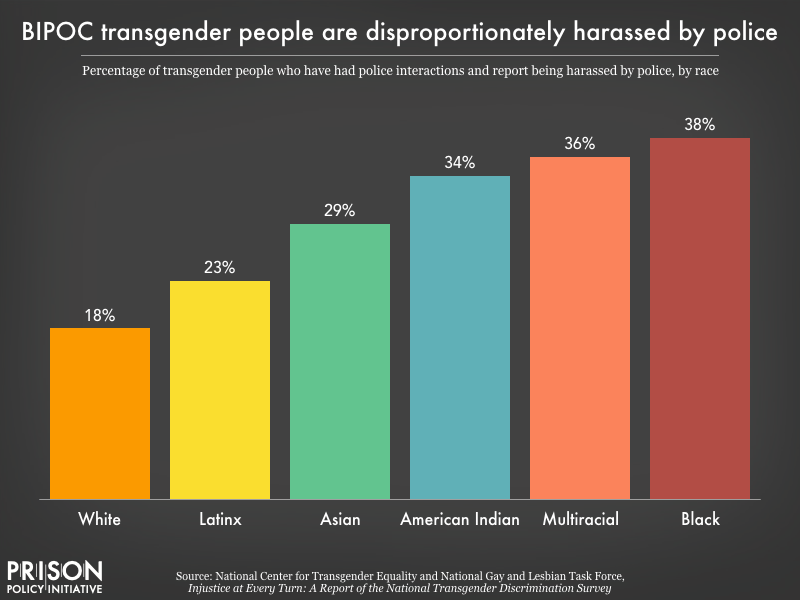

Trans people in the criminal justice system

There is significantly less data available on trans individuals in the criminal justice system. There is no data on transgender arrest rates, but other research shows police are extremely biased against trans people, especially Black trans people. According to the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force’s Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, nearly half of trans people reported that they do not feel comfortable seeking help from police. 1 in 5 trans people who have had police contact reported that they have been harassed by police, include 38% of Black trans individuals. Six percent reported that police have physically assaulted them and 2% reported that police have sexually assaulted them. Assault rates were even higher for Black trans people, with 15% reporting physical abuse and 7% of them reporting sexual assault by police.

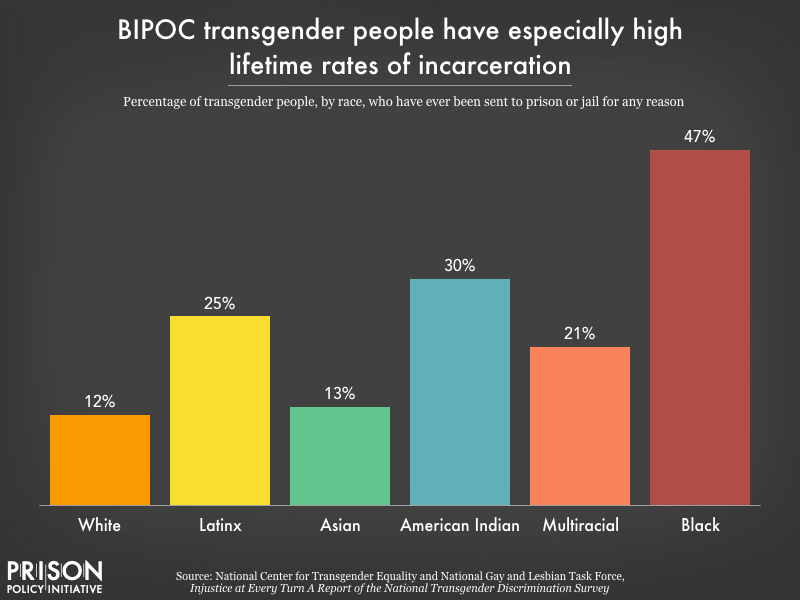

There is also limited data on trans incarceration. The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that there are over 3,200 transgender people in U.S. prisons and 1,827 in local jails nationwide. However, this might be an underestimate: In 2020, NBC News found that there were 4,890 transgender people locked up in state prisons alone. And according to data from The National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 1 in 6 trans people have been incarcerated at some point, and nearly half (47%) of Black trans people have been incarcerated:

Once behind bars, trans people face extremely high rates of harassment and physical and sexual assault, are frequently denied routine healthcare, and are at high risk of being sent to solitary confinement. Black and Pink found that 44% of transgender, nonbinary gender, and Two‐Spirit in their sample were denied access to hormones they requested. And as our previous study found, most states do not have policies ensuring basic protections for trans people behind bars. And most prisons in the U.S. currently house transgender people by their sex assigned at birth or according to genital characteristics, not their gender identity, which only increases their risk of harassment and assault.

Conclusion and recommendations

The data consistently shows that LGBTQ people are overrepresented throughout the criminal justice system and that they are subjected to especially harmful conditions behind bars. The Movement Advancement Project and Center for American Progress have explained how discrimination and stigma – like family rejection, poverty, unsafe schools, and employment discrimination – leads to criminalization. They argue that ending the criminalization of LGBTQ people will require broad social and policy changes, including (but not limited to):

- Increasing support for LGTBQ youth within families, schools, communities, and other institutions

- Eliminating discrimination against LGBTQ people in housing, employment, and other realms

- Eliminating homelessness among the LGBTQ population

- Ending the criminalization of sex work

- Enacting drug policy and sentencing reforms

While the central goal should be keeping LGBTQ people out of prison in the first place, far more needs to be done to ensure their safety behind bars, by preventing harassment and sexual assault, improving systems for addressing assault when it occurs, providing access to appropriate housing, health care, and clothing to incarcerated transgender people, and enacting and enforcing non-discrimination policies for staff.

Footnotes

- A note about language used in this briefing: We most often use the term LBGTQ to refer to gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer people in the criminal justice system, to best match the data sources we used. In a few places, we depart from the LBGTQ acronym to reflect other groups explicitly included in the data source we reference (for instance, in the section about youth in the juvenile justice system, where “questioning” youth are included), or where a group is explicitly excluded (the studies analyzing the National Inmate Survey, for example, do not address people who identify as transgender). Unfortunately, government data on gender and sexuality in the criminal justice system do not allow us to see whether intersex, asexual, gender nonconforming, two spirit people, and other groups within the queer community are also overrepresented in our criminal justice system.

- Specifically, Irvine & Canfield (2016) “found that 60.1% of girls in the juvenile justice system are heterosexual and gender conforming; 7.8% are heterosexual and gender nonconforming (more masculine presenting or behaving); 22.9% of girls are lesbian, bisexual, or questioning and gender conforming; and 9.2% of girls are lesbian, bisexual, or questioning and gender nonconforming.” (Chart 2, page 249)

- Future researchers should note that a breakdown of the offenses for which LGBTQ people are disproportionately arrested is a remaining data gap.

- Gay and bisexual men are not overrepresented in jails, where 3.3% are gay or bisexual men and 2.9% report having had sex with men before arrival at the facility but do not self-identify as gay or bisexual.