Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie

A Prison Policy Initiative briefing

By Peter Wagner and Leah Sakala March 12, 2014

This report is old. See our new version.

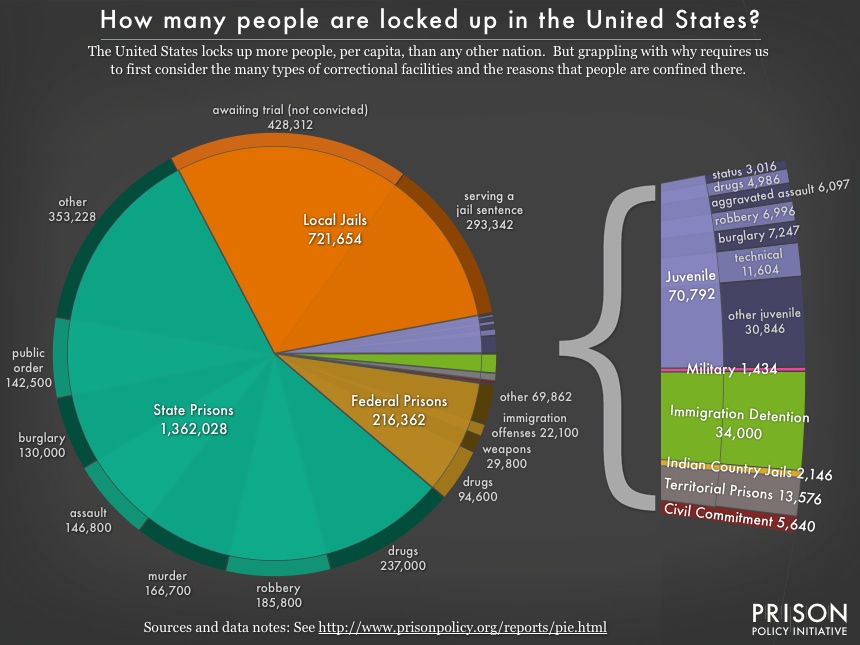

Wait, does the United States have 1.4 million or more than 2 million people in prison? And do the 688,000 people released every year include those getting out of local jails? Frustrating questions like these abound because our systems of federal, state, local, and other types of confinement — and the data collectors that keep track of them — are so fragmented. There is a lot of interesting and valuable research out there, but definitional issues and incompatibilities make it hard to get the big picture for both people new to criminal justice and for experienced policy wonks.

On the other hand, piecing together the available information offers some clarity. This briefing presents the first graphic we’re aware of that aggregates the disparate systems of confinement in this country, which hold more than 2.4 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 2,259 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,283 local jails, and 79 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, and prisons in the U.S. territories.1

While the numbers in each slice of this pie chart represent a snapshot cross section of our correctional system, the enormous churn in and out of our confinement facilities underscores how naive it is to conceive of prisons as separate from the rest of our society. In addition to the 688,000 people released from prisons each year2, almost 12 million people cycle through local jails each year.3 Jail churn is particularly high because at any given moment most of the 722,000 people in local jails have not been convicted and are in jail because they are either too poor to make bail and are being held before trial, or because they’ve just been arrested and will make bail in the next few hours or days. The remainder of the people in jail — almost 300,000 — are serving time for minor offenses, generally misdemeanors with sentences under a year.

So now that we have a sense of the bigger picture, a natural follow-up question might be something like: how many people are locked up in any kind of facility for a drug offense? While the data don’t give us a complete answer, we do know that it’s 237,000 people in state prison, 95,000 in federal prison, and 5,000 in juvenile facilities, plus some unknowable portion of the population confined in military prisons, territorial prisons and local jails.

Offense figures for categories such as “drugs” carry an important caveat here, however: all cases are reported only under the most serious offense. For example, a person who is serving prison time for both murder and a drug offense would be reported only in the murder portion of the chart. This methodology exposes some disturbing facts, particularly about our juvenile justice system. For example, there are almost 15,000 children behind bars whose “most serious offense” wasn’t anything that most people would consider a crime: almost 12,000 children are behind bars for “technical violations” of the requirements of their probation or parole, rather than for a new specific offense. More than 3,000 children are behind bars for “status” offenses, which are, as the U.S. Department of Justice explains: “behaviors that are not law violations for adults, such as running away, truancy, and incorrigibility.”4

Turning finally to the people who are locked up because of immigration-related issues, more than 22,000 are in federal prison for criminal convictions of violating federal immigration laws. A separate 34,000 are technically not in the criminal justice system but rather are detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), undergoing the process of deportation, and are physically confined in special immigration detention facilities or in one of hundreds of individual jails that contract with ICE.5 (Notably, those two categories do not include the people represented in other pie slices who are in some early stage of the deportation process because of their non-immigration-related criminal convictions.)

Now that we can, for the first time, see the big picture of how many people are locked up in the United States in the various types of facilities, we can see that something needs to change. Looking at the big picture requires us to ask if it really makes sense to lock up 2.4 million people on any given day, giving us the dubious distinction of having the highest incarceration rate in the world. Both policy makers and the public have the responsibility to carefully consider each individual slice in turn to ask whether legitimate social goals are served by putting each category behind bars, and whether any benefit really outweighs the social and fiscal costs. We’re optimistic that this whole-pie approach6 can give Americans, who seem increasingly ready for a fresh look at the criminal justice system, some of the tools they need to demand meaningful changes to how we do justice.

Notes on the data

This briefing draws the most recent data available as of March 13, 2014 from:

- Jails: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates at Midyear 2012 - Statistical Tables page 1 and table 3, reporting data for June 30, 2012.

- Immigration detention: Congress Mandates Jail Beds for 34,000 Immigrants as Private Prisons Profit, Bloomberg News, Sept 24, 2013.

- Federal: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2011, page 1 and table 11 from data as of December 31, 2011.

- State Prisons: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2011, Table 9, reporting data for December 31, 2010.

- Military: Correctional Populations in the United States, 2012 Appendix Table 2, reporting data for 2012.

- Territorial Prisons, Prisons in U.S. Territories (American Samoa, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) and U.S. Commonwealths (Northern Mariana Islands and Puerto Rico): Correctional Populations in the United States, 2012 Appendix Table 2, reporting data for 2012 includes both prisons and jails.

- Juveniles: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement, 2010, reporting data for February 24, 2010.

- Civil Commitment: Deidre D'Orazio, Ph.D., Sex Offender Civil Commitment Programs Network Annual Survey of Sex Offender Civil Commitment Programs, 2013.

- Indian Country (correctional facilities operated by tribal authorities or the Bureau of Indian Affairs): Bureau of Justice Statistics Correctional Populations in the United States, 2012 Appendix Table 2, reporting data for June 29, 2012.

Several data definitions and clarifications may be helpful to researchers reusing this data in new ways:

- The state prison offense category of “public order” includes weapons, drunk driving, court offenses, commercialized vice, morals and decency offenses, liquor law violations, and other public-order offenses.

- The state prison “other” category includes offenses labeled “other/unspecified” (7,900), manslaughter (21,500), rape (70,200), “other sexual assault” (90,600), “other violent” (43,400), larceny (45,900), motor vehicle theft (15,000), fraud (30,800) and “other property” (27,700).

- The federal prison “other” category includes people who have not been convicted or are serving sentence of under 1 year (19,312), homicide (2,800), robbery (8,100), “other violent” (4,000), burglary (400), fraud (7,700), “other property” (2,500), “other public order offenses” (17,100) and a remaining 7,850 records that could not be put into specific offense types because the “2011 data included individuals commiting drug and public-order crimes that could not be separated from valid unspecified records.”

- The juvenile prison “other” category includes criminal homicide (924), sexual assault (4,638), simple assault (5,445), “other person” (1,910), theft (3,759), auto theft (2,469), arson (533) “other property” (3,029), weapons (3,013) and “other public order” (5,126).

- To minimize the risk of anyone in immigration detention being counted twice, we removed the 22,870 people — cited in Table 8 of Jail Inmates at Midyear 2012 — confined in local jails under contract with ICE from the total jail population and from the numbers we calculated for those in local jails that have not been convicted. (Table 3 reports the percentage of the jail population that is convicted (39.4%) and unconvicted (60.6%), with the latter category also including the immigration detainees held in local jails.)

- At least 17 states and the federal government operate facilities for the purposes of detaining people convicted of sexual crimes after their sentences are complete. These facilities and the confinement there are technically civil, but in reality are quite like prisons. They are often run by state prison systems, are often located on prison grounds, and most importantly, the people confined there are not allowed to leave.

Acknowledgements

Thanks especially to Drew Kukorowski for collecting the original data for this project and to Alex Friedmann for both identifying ways to update the data, and for locating the civil commitment data. We thank Tracy Velázquez and Josh Begley for their insights on how to use color to tell this story. Thanks to Holly Cooper, Cody Mason, and Judy Greene for helping to untangle the immigration-related statistics. Thanks also to Arielle Sharma and Sarah Hertel-Fernandez for their copy editing assistance.

Footnotes

The number of state and federal facilities is from Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2005, the number of juvenile facilities from Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement, 2010, the number of jails from Census of Jail Facilities, 2006 and the number of Indian Country jails from Jails in Indian Country, 2012. We aren’t currently aware of a good source of data on the number of the facilities of the other types. ↩

U.S. Department of Justice, Prisoners in 2011, page 1, reporting that 688,384 people were released from state and federal prisons in 2011. ↩

See page 3 of Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates at Midyear 2012 - Statistical Tables for this shocking figure of 11.6 million. ↩

See Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement, 2010 page 3. ↩

Of all of the confinement systems discussed in this report, the immigration system is the most fragmented and the hardest to get comprehensive data on. We used Congress Mandates Jail Beds for 34,000 Immigrants as Private Prisons Profit, Bloomberg News, Sept 24, 2013. Other helpful resources include Privately Operated Federal Prisons for Immigrants: Expensive. Unsafe. Unnecessary, Dollars and Detainees The Growth of For-Profit Detention and The Math of Immigration Detention. ↩

It is important to remember that the correctional system pie is far larger than just prisons and includes another 3,981,090 adults on probation, and 851,662 adults on parole. See Appendix tables 2 and 4 in Bureau of Justice Statistics, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2012. ↩

Events

- April 30, 2025:

On Wednesday, April 30th, at noon Eastern, Communications Strategist Wanda Bertram will take part in a panel discussion with The Center for Just Journalism on the 100th day of the second Trump administration. They’ll discuss the impacts the administration has had on criminal legal policy and issues that have flown under the radar. Register here.

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.