Donate

Fighting against excessive and ineffective geography-based penalties

Since 2006, we’ve been working to reform one of the worst ideas to comes out of the war on drugs: large “sentencing enhancement zones” around schools. We’ve produced three reports demonstrating that these laws do not work, will never work, and worsen racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

Read on for more about our research and victories:

The problem

In most states, certain drug offenses committed within 1,000 feet of schools are punished with a longer sentence. The original intent behind these laws was noble: to protect children by creating an incentive for bad activity to move away from schools.

The flaw is that the designated distances are almost always too large. To create a safety zone around schools, the “protected” area needs to be small enough to incentivize moving illegal activity elsewhere. Imposing a higher penalty over an entire city or state by blanketing it in overlapping enhancement zones nullifies the legislatures’ effort to give schools special protection. Simply put, when a legislature says that every place is special, no place is special.

The flaw is that the designated distances are almost always too large. To create a safety zone around schools, the “protected” area needs to be small enough to incentivize moving illegal activity elsewhere. Imposing a higher penalty over an entire city or state by blanketing it in overlapping enhancement zones nullifies the legislatures’ effort to give schools special protection. Simply put, when a legislature says that every place is special, no place is special.

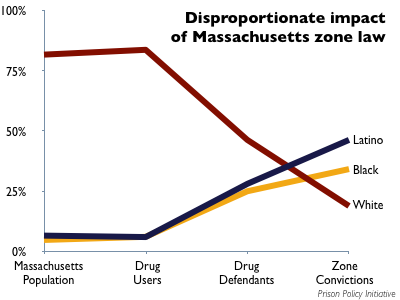

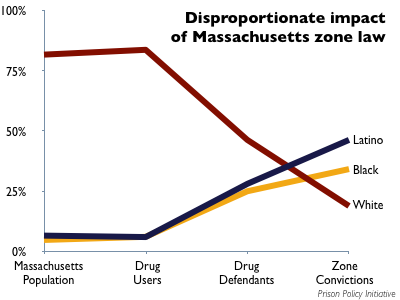

These “sentencing enhancement zone” laws, which swept the nation at the height of the War on Drugs, have never served their intended deterrent effect. But what they have done is consume resources that could otherwise go to protecting children effectively. They have also created a two-tiered system of justice: a harsher one for dense urban areas with numerous schools and overlapping zones, and a milder one for rural and suburban areas, where schools are few and far between. Moreover, in many cities, people of color are more likely than white people to live in sentencing enhancement zones, leading to stark racial disparities in sentencing.

Our work

Our first-of-its-kind research proved that sentencing enhancement zones are ineffective and unfair. Our reports and testimony spurred Massachusetts and Connecticut to reform their laws,1 and created a template for advocates in other states to follow:

-

Reaching too far: How Connecticut’s large sentencing enhancement zones miss the mark

Reaching too far: How Connecticut’s large sentencing enhancement zones miss the mark

by Aleks Kajstura, March 2014.

This report analyzes Connecticut’s 1,500-foot sentencing enhancement zones, mapping the zones in the state’s cities and towns and demonstrating both that the law is ineffective, and that it creates an “urban penalty”. -

Reaching too far, coming up short: How large sentencing enhancement zones miss the mark

Reaching too far, coming up short: How large sentencing enhancement zones miss the mark

by Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner and Leah Sakala

January, 2009.

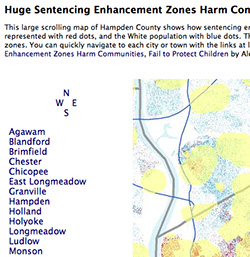

We find that in Hampden County, Massachusetts, Black residents are 26 times as likely, and Latinos 30 times as likely, as white residents to be convicted and receive a mandatory sentencing enhancement zone sentence. -

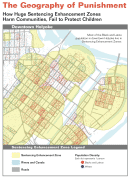

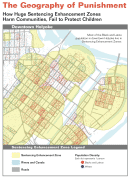

The Geography of Punishment: How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children

The Geography of Punishment: How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children

by Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner and William Goldberg, July 2008.

This first-of-a-kind report mapped every sentencing enhancement zone in urban, rural and suburban Hampden County, and quantified the race and ethnicity of the people who live inside and outside of the zones.

Related advocacy and resources

- Our friends at the Sentencing Project published a state-by-state summary of each state’s sentencing enhancement zone laws in 2015.

- Our video explaining why sentencing enhancement zones are unfair and ineffective.

- 1,000 Feet is Further Than You Think is a graphical introduction to distance. We’ve also made this resource available as a powerpoint presentation.

- A second slideshow illustrating how far 1,500 feet really is, for states with larger sentencing enhancement zones.

Coverage of our work:

- War of words between Malloy and the GOP over accusations of racism, Mike Krafcik, Doug stewart and Samantha Schoenfeld, Fox CT, May 14, 2015

- The Hidden Price Of Drug-Free Zones, Christie Thompson, ThinkProgress, April 14, 2014

- Lawmakers Debate Drug-Free School Zones, Amaris Elliott-Engel, The Connecticut Law Tribune March 28, 2014

Zones: Effective Deterrent? Are they an effective deterrent, or just a lever to force lesser pleas from drug offenders? The new DA Talks About Drug-Free School Zones, by Maureen Turner, Valley Advocate, March 18, 2011

Zones: Effective Deterrent? Are they an effective deterrent, or just a lever to force lesser pleas from drug offenders? The new DA Talks About Drug-Free School Zones, by Maureen Turner, Valley Advocate, March 18, 2011 Rethinking Drug-Free School Zones: Gov. Patrick proposes changing a policy critics say is unfair and ineffective, by Maureen Turner, Valley Advocate February 10, 2011

Rethinking Drug-Free School Zones: Gov. Patrick proposes changing a policy critics say is unfair and ineffective, by Maureen Turner, Valley Advocate February 10, 2011 The too-long arm of the law, by Boston Globe editorial board, February 1, 2011

The too-long arm of the law, by Boston Globe editorial board, February 1, 2011 “Urban Penalty: Do drug-free school zones unfairly target cities and people of color?”, by Maureen Turner, Valley Advocate (Western Massachusetts) February 26, 2009.

“Urban Penalty: Do drug-free school zones unfairly target cities and people of color?”, by Maureen Turner, Valley Advocate (Western Massachusetts) February 26, 2009. “You’re Probably in a Drug-Free School Zone Right Now: For all the good it does”, by Chris Faraone, Boston Phoenix February 11, 2009.

“You’re Probably in a Drug-Free School Zone Right Now: For all the good it does”, by Chris Faraone, Boston Phoenix February 11, 2009.-

“Drug free zones facing review”, by Jo-Ann Moriarty, The Republican (Springfield, MA) July 26, 2008.

“Drug free zones facing review”, by Jo-Ann Moriarty, The Republican (Springfield, MA) July 26, 2008.

Footnotes

-

In 2012, Massachusetts reduced the sentencing enhancement zones from 1,000 to 300 feet and reduced the hours when the enhancement is in effect. In 2015, Connecticut repealed the mandatory nature of the state’s 1,500 foot sentencing enhancement zone. We played an active role in evaluating the many compromise proposals and while we had wanted both states to go further in their final bills, both state’s reforms greatly reduced the impact of these draconian laws. ↩

Zones: Effective Deterrent?

Zones: Effective Deterrent? Rethinking Drug-Free School Zones:

Rethinking Drug-Free School Zones: The too-long arm of the law

The too-long arm of the law