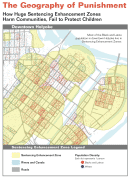

The Geography of Punishment:

How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children

by Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner, and William Goldberg

Prison Policy Initiative

July 2008

Section:

Introduction

Massachusetts currently enforces a strict mandatory minimum sentence for certain drug offenses committed near schools and parks. Originally adopted in 1989 and expanded twice,[1] the law is one of many statutes aimed at protecting children by steering drugs and related harmful behaviors away from areas where children congregate.

The sentencing enhancement zone laws have mostly escaped public scrutiny, despite a growing body of evidence that the zones fail to protect children and that defendants are often eligible for the mandatory minimums based on their places of residence, not the severity of their offenses.

Though the statute aims to protect children, its patterns of conviction indicate that it has more effectively created a two-tiered system of drug sentencing in Massachusetts. Because schools are more numerous in dense urban areas, most urban residents — including most of the state’s Black and Latino residents — face longer mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses than the state’s rural residents, who are predominantly White.

This human cost is accompanied by a staggering fiscal cost. By continuing to enforce the sentencing enhancement zone law, the Commonwealth is spending huge sums to incarcerate minor drug offenders who were not endangering children: the 727 people in prison or jail for zone violations are approximately 3.1% of the state’s incarcerated population. It costs $43,025.63 per year to incarcerate a drug addict and $4,970 per year to treat him.[2] Confining these addicts costs the state more than $31 million a year, when it would cost much less to help them more effectively.[3] This enormous cost excludes the unknowable number of people who pled guilty to zone charges to avoid the mandatory minimum. As the state’s budget deficit is predicted to surpass $3 billion,[4] it is both ethically and fiscally necessary to reform legislation that incarcerates large numbers of people for long periods for minor offenses.

This report examines the geography of the areas covered by Massachusetts’ sentencing enhancement zone law. We set out to answer two questions:

- Does the sentencing enhancement zone law punish certain populations more harshly because of where they live?

- Is 1,000 feet a logical or effective distance for a geography-based sentencing enhancement?

Our mapping work focuses on Hampden County, which is located in the western part of the state and contains the cities of Holyoke and Springfield, as well as very rural towns like Tolland and Blandford. As a percentage of its total population, the county has the second largest minority population in the state, after Suffolk County (Boston). It also has the second highest poverty rate in the state, the highest poverty rate for children under 5, and the third highest rate of adults without a high school diploma or GED.[5]

Despite these pressing needs, much of the state’s investment in Hampden County goes to criminal justice. Hampden County is twice as likely to charge its citizens with drug offenses as the state as a whole,[6] and according to the most recent data available, uses the sentencing enhancement zone law more than any other county: two and half times the state average. (See Table 1.)

| District Court Drug Charges (FY1998) | District Court Drug Charges per 1000 People | Sentencing Enhancement Zone Convictions (FY1998) | Sentencing Enhancement Convictions per 1000 Drug Charges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barnstable | 1,095 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Berkshire | 622 | 4 | 9 | 14.2 |

| Bristol | 5,204 | 10 | 14 | 2.7 |

| Dukes | 122 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Essex | 6,221 | 9 | 23 | 3.7 |

| Franklin | 330 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Hampden | 6,760 | 15 | 108 | 16.0 |

| Hampshire | 723 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Middlesex | 6,027 | 4 | 42 | 7.0 |

| Nantucket | 30 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Norfolk | 2,477 | 4 | 6 | 2.4 |

| Plymouth | 3,074 | 7 | 26 | 8.4 |

| Suffolk | 11,559 | 18 | 75 | 6.5 |

| Worcester | 6,191 | 8 | 13 | 2.1 |

| TOTAL/AVG | 50,435 | 8 | 316 | 6.3 |

While it is outside the scope of this report to explain the differences in zone enforcement between Hampden County and the state as a whole, the county’s internal diversity and frequent use of the zone law make it an ideal place to study the geography and demography of the enhancement zones.

According to the most comprehensive national report on sentencing enhancement zones, Disparity by Design, almost every state has its own version of the enhancement zone law.[7] Massachusetts’ 1,000-foot distance is the most common, but the zones’ size, the locations they surround, and other specifics vary greatly.

The Massachusetts law requires that the distance be measured in a straight line from the property line of the school or other designated area. The offender need not know he is in a zone to face an enhanced penalty, and adjoining unused school-owned land also qualifies as school property. The law operates regardless of whether school is in session or children are present. In Massachusetts and most states, the sentencing enhancement must be served separately from the sentence for the underlying offense. Massachusetts’ mandatory minimum sentence is 2 or 2 1/2 years depending on whether the defendant is charged in District or Superior Court.

Footnotes

[1] A 1993 amendment added a 100-foot zone around parks and playgrounds, and a 1998 amendment added accredited daycare and Head Start facilities to the list of schools with a 1,000-foot zone.

[2] Massachusetts Department of Health, COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS SUBSTANCE ABUSE STRATEGIC PLAN 25, May 16, 2005 available at http://www.tbf.org/uploadedFiles/CJI_11.2.05.pdf.

[3] According to the Massachusetts Sentencing Commission, in fiscal year 2004, 281 people were sentenced to two-year mandatory minimum sentences in Houses of Correction and 66 people were sentenced to two-and-a-half year prison sentences. Multiplying the number of people sentenced by the sentence lengths allows us to estimate the number of people incarcerated in any given year for zone offenses. The Massachusetts Department of Corrections estimates that it costs $43,025.63 to incarcerate one person for a year.

[4] Kristen Lombardi, Cheap Trick: Cash-strapped state legislators are finally considering relaxing mandatory drug sentences, BOSTON PHOENIX, January 26, 2007.

[5] U.S. Census 2000, Summary Files 1 and 3. See Appendix A.

[6] Massachusetts Court System, Fiscal Year 2005 Statistics, Criminal Cases - By Court, available at http://www.mass.gov/courts/courtsandjudges/courts/districtcourt/crimstats2005_page3.html and U.S. Census 2000. See Appendix B.

Events

- April 30, 2025:

On Wednesday, April 30th, at noon Eastern, Communications Strategist Wanda Bertram will take part in a panel discussion with The Center for Just Journalism on the 100th day of the second Trump administration. They’ll discuss the impacts the administration has had on criminal legal policy and issues that have flown under the radar. Register here.

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.