Peter Wagner's commentary on and suggestions for changes to the proposed Ohio Inmate Rules of Conduct

by Peter Wagner,

November 24, 2003

To:

James Guy

DRC Central Office, Legal Services Section

Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction

1050 Freeway Drive North

Columbus, Ohio 43229

Re: Comments on Proposed Administrative Rules 5120-9-06, Inmate rules of conduct

Dear Mr. Guy:

I am Assistant Director of the Prison Policy Initiative, a Cincinnati based research and policy organization with an interest in the proposed 5120-9-06 inmate rules of conduct. My experience on this issue comes from my law school internships, where I worked on prison disciplinary hearing issues at Massachusetts Correctional Legal Services and at the Lewisburg Prison Project where I edited a national guide on the issue.

As the existing rules state more eloquently than I, the overarching purpose of a prison disciplinary procedure is to guide and correct prisoner behavior for future reintegration into free society and to ensure the orderly running of the institution. I am concerned that, by structure and omission, the proposed rules undermine the orderly running of your institutions.

Simple, clear rules and procedures are respected by both prisoners and staff and provide stability to a very tense environment. Rules that are confusing, duplicative, impossible to enforce, or violate obvious public policies undermine the value of a disciplinary system.

I have a number of suggestions for rules that can be combined, and I discuss several rules that are unnecessary or counterproductive, and then I have a very serious concern about the deletion of the policy statement for the disciplinary process.

Duplicative rules

The goal of this regulation is to give prisoners notice of the rules and guidance to staff in guiding prisoner behavior. Duplicative charges make the policy difficult for prisoners to digest and difficult for staff to implement. Because the policy does not explicitly prohibit multiple charges or multiple guilty findings arising from the same act, there is also the possibility of giving a prisoner a higher punishment than the actual act warranted.

For example, the proposed regulations make separate rule violations to “cause physical harm”, to “cause serious physical harm”, and to “cause physical harm with a weapon”. I assume the Department does not mean to suggest that another combination, causing serious physical harm with a weapon, would be acceptable behavior. This omission illustrates that proliferating rules for every imagined situation runs counter to the Department’s and Legislature’s intent to provide an orderly institution.

The most efficient procedure would be to combine duplicative rules and to create a specific regulatory instruction to hearing officers that wherever more than one rule covers the same act, the charges should be consolidated into the most serious charge. The hearing officer should determine the severity of the punishment in accordance with the severity of the act(s) and not with the technical number of rules violated.

Based upon a quick review, I found the following rules that could be easily combined, sometimes with edits as small as two words:

- Rules 3, 4 & 5. Causing or attempting to cause physical harm.

- Rules 6 & 7. Throwing material and bodily fluids

- Rules 8 & 9. Threats.

- Rules 11, 12, 14 & 24e Non-consensual sexual contact and conduct

- Rules 20, 21, 22 & 23. Refusal to follow orders

- Rules 28 & 34. Forged documents for escape or other purposes

- Rules 29, 30, 31, 32 & 33. Escape. (This is a very broad category ranging from the possession of contraband to leaving the facility without permission and many things in between. Arguably it would be useful, if only for the purposes of a prisoner’s institutional record to have different types of “escape” charges, however as currently constructed all of these are so vague that without the full facts behind the charge a parole or classification officer would be hard pressed to compare the relative severity of these 5 rules.)

- Rules 36, 37 & 38. Weapons

- Rules 39 & 40. Drugs

Unnecessary or counter-productive rules:

A number of other rules are unnecessary and counterproductive to the corrective intent of the policy. The inclusion of such rules dilutes the value of the legitimate rules and creates opportunities for arbitrary enforcement or the perception that the rules are being enforced arbitrarily.

Rule 13. Prohibiting consensual sex.

Consensual sex is a frequent occurrence in prison and does not amount to an “immediate and direct threat to the security or orderly operation of the institution.”[1] The policy provides no reason why consensual sex should be prohibited and I am not aware of any legitimate correctional need to do so that can not be separately addressed by other existing rules.

Such a rule is unenforceable, as Director Wilkinson admits.[2]

Enforcement of this rule also sets back efforts to reduce the spread of sexually-transmitted diseases including HIV. Currently, 6 to 20% of Ohio’s prisoners have Hepatitis C. Nine out of every 1,000 male prisoners in Ohio are known to have HIV, a rate 4.5 times higher than the male public at large.[3] This situation is already a public health catastrophe. Creating a rule that assumes that consensual sex does not or should not happen prevents the Department from fulfilling its obligation to reduce the transmission of disease. When the Akron Beacon Journal asked Director Wilkinson about distributing condoms to prisoners to stop the spread of HIV as is done in Vermont, he replied: “Absolutely not…. And it will never happen. To me, it would condone the possibility of inmates having sex.”[3] Changing this rule would free the Department to pursue alternative means of combating the spread of HIV and Hepatitis C in prison populations.

The final conceivable justification for such a rule could be to punish prisoner rape where evidence of non-consent is lacking for a finding of guilt under Rule 12 (non-consensual sex). But such an interpretation is both unrealistic and self-defeating. Given the very low “some evidence” standard of proof used by the Ohio Department, it is hard to imagine a situation where “some evidence” did not exist and yet a guilty finding would be warranted. If viewed as a “backup” rule to penalize prisoner rape, the rule is self-defeating because the prohibition would subject both rapist and victim to equal punishment. Punishing rape victims will reduce reporting and slow the state’s progress towards eliminating prisoner rape. With no legitimate justification for this rule, it should be removed.

Rule 14. Prohibiting masturbation and other acts.

Everybody masturbates. Perhaps, deprived of their usual partners, prisoners may masturbate more than the average person. Some commentators would argue that masturbation is healthy, but no credible argument can be made that masturbation in itself causes harm to anyone. Likewise, it is impossible to consider a ban on masturbation that would be consistently enforced. The presence of the rule against masturbation and any enforcement of it would undermine the legitimacy of the disciplinary system.

Of course, masturbation at inappropriate times or places, or other inappropriate sexual acts in front of others can be considered “conduct” and included in with Rule 11.

Rule 24e. Prohibiting engaging in or soliciting sexual acts with employees.

This rule should be removed as being duplicative in part, and contrary to public policy in the remaining part. Unwanted sexual advances from prisoners towards employees should be considered a part of Rule 11, non-consensual sexual conduct. The remaining portion of Rule 24e would cover consensual sexual conduct between prisoners and staff but its enforcement would undermine the legislature’s efforts to eliminate such activity.

There is currently an evolving national consensus to bar sexual contact between prisoners and staff. Recognizing the manipulative power of staff to demand sex from prisoners, the majority of state legislatures now treat these offenses as statutory rape. Ohio is a part of this national consensus, considering sexual penetration, regardless of consent, of a prisoner by staff to be sexual battery, a felony of the third degree.[4]

This rule penalizes prisoners with disciplinary sanctions for being statutorily raped and then reporting such a crime, and would give staff perpetrators additional leverage to ensure their prisoner-victim’s silence. This rule should be removed because it will have a contrary effect on the legislature’s attempts to prohibit this behavior by prison staff.

Rule 57 and the last clause in Rule 59: Prohibiting various forms of self-harm.

Rule 57 prohibits “self-mutilation, including tattooing” and Rule 59 includes a prohibition on acts that are a threat to “the acting inmate”. The Department is charged with protecting the health and safety of the prisoners in its care, but treating these dangerous practices as disciplinary problems is ill-advised and runs contrary to the Department’s mission.

The prohibition on tattooing devices and material (Rule 58) is an appropriate disciplinary strategy and should be retained in so far as these materials can be distinguished from their legitimate uses (ie. ball point pens still in their original form).

But the Department’s proposed Rule 57 would discourage recently tattooed prisoners from delaying medical treatment if an infection arises. The staph epidemic this summer should be illustrative of the problems caused by delayed treatment of infections. By analogy, the administrators at Pickaway and Belmont Correctional Institutions suspended medical co-payments during the staph infection outbreak this summer in order to remove any impediments on prisoners seeking medical care. Ideally, prisoners would not attempt to give themselves tattoos in un-sterile situations. In the mean time, the best solution is to ban tattooing tools, educate against tattooing and to be on the alert for the medical problems caused by it. Prohibiting tattooing runs contrary to this public policy.

Likewise, self-mutilation and self-harm (Rules 57 and 59) are acts that are medical emergencies rather than disciplinary problems. Even under the most cynical view, a prisoner that harms himself “for attention” is in fact in serious need for medical attention. Self-mutilation is often a warning sign of deeper mental problems. Furthermore, punishing mentally ill prisoners with reduced privileges or worse, segregation, increases the risk of self-harm or suicide.

According to Raymond Bonner, suicide prevention expert and chief psychologist at the Federal Correctional Institution at Allenwood, Pennsylvania, “Social and environmental isolation is never an appropriate consequence [of acts of self-harm or attempted suicide] as it undoubtedly worsens emotional state, hinders problem-solving and can increase the risk for life-threatening behavior.”[5]

Dr. Bonner’s quotation is in a chapter entitled Suicide and Self-Mutilation in a new report from the internationally well-respected organization Human Rights Watch. I have attached this chapter to my testimony to provide further evidence that these rules threatening punishment for self-mutilation and self-harm are contrary to any legislative mandate to protect prisoner health and safety.

Deletion of statement of guilding principles undermines policy

Perhaps most troubling is the change in the guiding principles for the disciplinary policy. The previous protective and helpful statement of principles has been gutted. These principles are necessary staff guidance in interpreting and implementing the rules and are necessary for prisoners to be able to understand and respect the rules. In my experience, I have found that arbitrariness is a direct threat to the orderly operation of a prison.

The current policy reads:

(H) Institutional rules: Rules governing the conduct of offenders and the consequences which may follow from a violation shall be printed and furnished to the inmates together with any explanations that may be necessary for their guidance. Rules shall be corrective, not abusive or punitive, in purpose. They shall be no more numerous or restrictive than is necessary to produce responsible and orderly conduct, and be related to valid institutional concerns.

(I) Discipline: Enforcement of institutional rules shall be for the purpose of developing patterns of behavior which will be of help to the inmate in his future adjustment in the free community, and the maintenance of order in the institution. Enforcement of institutional rules shall be rehabilitation oriented, and for the purpose of developing self-control and self-discipline. No action shall be taken against an inmate for the violation of a rule except in accordance with established disciplinary procedures. Use of correctional cells with deprivation of cell privileges as punishment is authorized but should be used only when clearly necessary.

(J) Restrictions on personal privileges: Disciplinary restrictions on clothing, bedding, mail, visitations, or the use of toilets, washbowls, and showers may be imposed only following an inmate’s abuse of such privileges or facilities or when such action is deemed necessary by the managing officer for the safety or security of the institution, or the well being of the inmate, and shall continue only as long as is absolutely necessary.

The equivalent text in the proposed regulation reads in its entirety:

(E) Institutional rules: rules governing the conduct of offenders and the consequences which may follow from a violation shall be published and made readily available to inmates. Rules shall be corrective, not abusive or punitive, in purpose.

Ohio is one of only two states to retain “Rehabilitation” in the name of its Department. Going beyond the name, Ohio is in many respects, a national leader on effective rehabilitation. But the wholesale deletion of these detailed requirements that punishment be proportional to the offense, with prior notice of the rules and for the rationale to be explained to the prisoner suggests that, at a policy level, the Department wishes to repeal, as it applies to prisoners, the entire principle of due process.

Given what I know about the leadership role that Ohio plays in corrections, I do not believe this regression was intentional and I strongly urge you to retain the original paragraphs in their entirety.

Thank you for the opportunity to present my views on this important matter of prison disciplinary procedures. If I can provide any additional information, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Sincerely,

Peter Wagner

Assistant Director

cc:

Mr. Bill Hills

Joint Committee on Agency Rule Review

77 S. High St., 8th Floor

Columbus, OH 43215

Enclosures:

Human Rights Watch, Ill-Equipped: U.S. Prisons and Offenders with Mental Illness, Chapter XIII, Suicide and Self-Mutilation

Prison’s hidden cost, Inmates can take home AIDS risk, Beacon Journal, March 17, 2002

Footnotes:

Ohio Department of Corrections' health care budget cuts and poor oversight is compromising the quality of care.

by Peter Wagner,

November 24, 2003

Ohio’s prisoners are dying from inadequate medical care

In August, the Columbus Dispatch and WBNS-TV published a multi-part exposé of the inadequate medical care in Ohio’s prisons. The series exposed wrongful deaths, inadequate care and questionable doctors. Almost 2,600 Ohio prisoners are known to be infected with Hepatitis C and health officials estimate the true figure to be closer to 9,000. As of July, the number of prisoners receiving treatment for Hepatitis C was 16. In September, the Prison Reform Advocacy Center in Cincinnati filed a class action lawsuit challenging these conditions.

The attention from the series brought shock from the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitations, but the problems appear to be the result of neglect engineered at the budgetary level.

This year Ohio will spend $122.6 million on prison health care. That’s not counting the $1.15 million in judgments and settlements over the last 3 years. This year, 25 of the prisons had their health care budgets cut an average of 11%. While medical care costs have risen 19% nationally since 2000, Ohio’s spending on prison health care has risen just 9%.

In 2002, the DRC’s health care director Kay Northrup asked medical providers to change their message to prisoners when denying care. Instead of explaining that a treatment refusal was based on budgetary reasons, doctors were to give out only clinical explanations. A year earlier, she ordered prison podiatrists to stop ordering special footwear for prisoners with unable to walk in the stiff-prison issued “shoes”. Admitting that the cheap shoes caused many foot problems, she restricted the doctors to ordering replacements only for diabetics who developed foot ulcers. The remainder of the injured were left, in the words of the Columbus Dispatch “hobbled”.

Restricting care, $3 at a time.

Ohio charges a $3 co-payment on medical visits to discourage them. The DRC director implies the fee cuts down on frivolous visits without impacting good health care, but administrators at Pickaway and Belmont Correctional Institutions disagreed when they suspended the fees after an outbreak of staph infections.

The co-payment has raised $1.7million since 1998 intended to fund expensive equipment purchases, but $1million of the money remains unspent.

Three dollars for a medical visit may not seem like a lot of money to people on the outside, but Ohio prisoners make only $18-24 a month. The Columbus Dispatch estimated that the $3 copayment would be the “equivalent of $594 to the average Ohio household earning $47,521 a year.”

Low-quality doctors

One of the doctors highlighted in the Columbus Dispatch was Dr. Adil Yamour, whom the London Correctional Institution’s health care administrator requested be replaced because he “orders ibuprofen for everything, regardless of the diagnosis.” The situation gets more frightening when you factor in his defense: he was asked to see 70 to 93 prisoners in an eight hour shift. Yamour was also criticized for telling prisoners he could not order certain procedures or medications because of lack of funding, which he claims was true. In any event, this doctor who the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation thought should be replaced was let go, and then started treating patients at Pickaway Correctional Institution via contractor Clinicare.

This may not be an extreme case. Dr. Shura Hedge was fired in 2001 after he was caught spending only 10 minutes to give full mental health evaluations, and he was giving the same assessment scores to 30 of 31 prisoners, “some of whom where psychotic.” He was hired by the privately-operated state prison across the street. The Columbus Dispatch identified two other medical workers who were fired or non-renewed and then resurfaced at other prisons. Although the state has veto rights over the personnel decisions of its private prison operators, Hedge is still working at his new prison.

Bad apples in rotten prison barrel

These bad apples are a structural product of Ohio’s policy of relying on outside contractors on lump-sum contracts. While the contractors do comply with requests to remove problematic doctors, no company has ever lost a contract for poor performance. The results are as unfortunate as they are unsurprising because the prisoner-patients are powerless and the DRC fails to require quality.

Likewise, the state has failed to do background checks in a timely way for its doctors. Dr. Ayman Kader worked in two Ohio prisons for more than a year while under a 35-count felony indictment for drug trafficking and writing bogus prescriptions for amphetamines.

Complicity for the poor care runs to the top. “We do have to tolerate a different standard sometimes because it’s hard to get people to come and work in the prisons to provide medical care,” says the DRC’s spokeswoman Andrea Dean. (See sidebar, International law and prisoner health for more on this claim.)

The contractor who hired Kader and called him “one of our most valued, cooperative physicians” echoed a similar sentiment to Dean: “People do not go to medical school dreaming of some day working in a maximum security prison.” The medical providers can be glib that “you get what you pay for” because they make a profit by providing doctors — inferior or otherwise — to the prison. The Department’s tolerance of the problems is harder to understand, unless adequate care is of no concern.

Working in a prison is not a prestigious job, but the pay scale reinforces rather than addresses the problem. While the comparative pay received by Ohio’s contractors was not available, other data collected by Human Rights Watch suggests that poor performance of prison doctors is by design, not accident. In Maine, a psychiatrist would make $20,000 less working in a prison than in the community. Virginia pays its prison psychiatrists $3,251 less per year than it pays school psychiatrists.

Ohio reduced prison medical costs by first replacing its own doctors with contractors paid on a per-hour basis and then with a series of fixed-rate contracts. Each year’s winning bid becomes the maximum amount the Department will pay in the next year. Under the hourly contractor system, Ohio paid $312,000 in wages at the typical prison in 2001. The current figure is $175,000, or 56% less.

Locked in to medical neglect

Unlike other victims of poor medical care, prisoners don’t have the ability to get a second opinion. Instead, prisoners are required to file administrative grievances. Attorney Alphonse Gerhardstein summarized the procedure: “The medical grievance goes to a bureaucrat, the bureaucrat then sends it to the medical staff, who then say, ‘We’re giving fine care. What’s the inmate griping about?’ Then they send the grievance back and deny it.”

The state’s own consultant recognizes the medical grievance system is broken, suggesting in 2001 that the grievances get independent medical review. No action was taken. And perhaps the State likes the lack of oversight. The legislature’s Correctional Institution Inspection Committee, which is supposed to oversee the prison systems, has gone without funding for staff for two years and this year is getting funding at only half of its previous amount.

Following up

What needs to be done is obvious. As Dr. Ronald Shansky, the former medical director of Illinois prisons told the Columbus Dispatch, that Ohio “‘needs an independent, outside team of correctional medical experts’ to review prison medicine…. ‘If the concerns are serious, the state should want to know. Is it getting a bang for its buck or is it creating liability?'”

The Department has created a commission to study the issue and recommend changes. The report, due at the end of the year should provide a clue as to whether Ohio policymakers want to provide adequate health care for its incarcerated citizens or adequate salaries for Department lawyers to defend lawsuits.

The Commission has hired the former head of the New Mexico DOC to assist, but the commission is all Department employees including Kay Northrup, the Deputy Director of the Office of Correctional Health Care and author of the memo instructing doctors to not tell prisoners the truth: that financial restrictions are determining their treatment.

Worse, perhaps, is the message sent to the Commission by the Department’s Director, Reginald Wilkinson. He acknowledges that reforms may cost money, but he’s “not throwing in the towel on money at this point” in the hopes that the Commission finds new ways to further cut the medical budget.

Sources: Columbus Dispatch, Human Rights Watch, Ill Equipped: U.S. Prisons and Mental Illness. The Andrea Dean quote can be seen online in the August 25, 2003 Cincinnati Enquirer Report: Waits lengthy to see prison doc.

Letter accompanying a submission of 'The Prison Index: Taking the Pulse of the Crime Control Industry' to the American Bar Association to inform its review of criminal justice policy.

by Peter Wagner and Brigette Sarabi,

November 3, 2003

The Western Prison Project and the Prison Policy Initiative sent this letter to members of the ABA Justice Kennedy Commission:

November 3, 2003

Dear Member of the ABA Justice Kennedy Commission,

The Western Prison Project and the Prison Policy Initiative were excited to learn that the ABA has answered the challenge issued by Justice Kennedy to examine U.S. incarceration policy. As you know, our nation’s recent reliance on incarceration as a one-size-fits-all solution to social problems has put the world’s foremost democracy into the unenviable position as the world’s leading denier of liberty.

In lieu of submitting formal testimony, we are sending to each member of your commission a copy of our newest report The Prison Index: Taking the Pulse of the Crime Control Industry. The report summarizes state of crime control in the United States, finding that a combination of sentencing policies and economic factors have created a criminal justice system that fails by all possible metrics but one: the creation of more prisoners.

We are heartened by your response to Justice Kennedy’s call to break this morally and economically bankrupt cycle of building more and more prisons to house ever greater numbers of our citizens in ever more deplorable conditions. We hope your forthcoming report will have great influence.

There is precedent for a nation taking the advice of its professional class and transforming its criminal justice policies. Finland used to have a high incarceration rate without a European peer — except for that of the Soviet Union. Coming out of World War II and into the Cold War, that was the last society Finland wanted to resemble. Like the United States, Finnish leaders had become accustomed to high levels of incarceration. Academic exchanges with foreign criminologists put the exceptionalism of the Finnish situation on the policy agenda. Once the highest incarcerator in Western Europe, Finland today incarcerates only 50 of its citizens per 100,000 people, second lowest after Iceland.

We hope that the reexamination of our criminal system you are seeking will lead to a similar transformation. There may not be a simple answer to the question “How low should the prison population be?” But we can clearly say that Finland does quite well with one tenth the incarceration rate of our country.

Sincerely,

Brigette Sarabi

Executive Director

Western Prison Project

Peter Wagner

Assistant Director

Prison Policy Initiative

Article by Peter Wagner explaining that up to three quarters of the crew members fighting California fires are prisoners who are paid up to one dollar per hour.

by Peter Wagner,

October 30, 2003

In California, up to three quarters of the crew members fighting California fires are prisoners. In exchange for a reduction in sentence length, 4,100 minimum security prisoners work fighting fires and on public works projects for a $1 or less an hour.

Prisoners contributed 3.1 million hours fighting fires in California last year, earning only $1 an hour. By contrast, the average forest fire fighter in the U.S. earns $17.19 an hour, or $35,760 a year. Prisoners working on public works projects earn even less, $40 a month.

Using prisoner labor saves the state of California $200 million a year, $80 million in salary and $120 million in employee benefits and security costs. With almost one-third of minimum security prisoners moved from behind razor wire and onto the fire-lines, corrections costs are therefore lower.

The program is not limited just to adult prisoners. Last year the California Youth Authority contributed 684,000 slave-hours to firefighting, saving the state $3.9 million. Of course, it does not appear any of the savings were redirected into college scholarships for previously incarcerated youths.

Prisoners take the jobs because it reduces their sentence, gets them outside, and pays better than the typical prison job. But there are risks. Four years ago a prisoner was killed when he fell 150 feet down a slope fighting a Ventura County fire. The prisoner profiled in the San Diego Union Tribune, Peter Quintana, explained how prisoners are so desperate to earn money or shorten their sentences that they jeopardize their own health working in unsafe conditions for low wages:

“He believes he broke a toe in March while clearing a fire line to slow a blaze near Lakeside. ‘It happens’ he said. ‘It was about 2 or 3 am and we didn’t have much light. I swung my Pulaski (a tool to clear vegetation) and it bounced off a branch and hit my toes.’ Rather than report the injury and risk being dropped from the program, Quintana said he ignored the pain and kept on working.”

Sources:

San Diego Union-Tribune August 12, 2003 and U.S. Department Bureau of Labor Statistics

Article discusses how rural prison expansion contributes to long-standing racial disparities between correctional officers and incarcerated people.

by Peter Wagner and Rose Heyer,

September 25, 2003

Originally published on September 25, 2003 on Alternet

By Peter Wagner and Rose Heyer

In September 1971, thousands of prisoners at Attica prison in rural New York State rebelled, taking control of D-yard. Sixty-three percent of the prisoners were black or Latino, but at that time there were no blacks and only one Latino serving as guards. Seventy percent of the prisoners were urban, mostly from New York City, but 80 percent of the guards were from rural New York.

The disparity between the keepers and the kept increased tensions at the prison by inserting a cultural gulf between guards and prisoners, and by giving black and Latino prisoners painful evidence that their fate was, in part, determined by race.

After four days of negotiations, Governor Rockefeller ordered an assault on the prison, turning what was then the largest prison rebellion into the bloodiest. Thirty-two prisoners and 11 guard hostages died, almost all in the retaking of the prison.

Attica and the investigation into its causes caused a fundamental reexamination of correctional policy throughout America. While food, mail policies and rehabilitative programs were improved, the demand for more black and Latino staff proved to be among the easiest to support and the most difficult to implement. Writing in 1973 about “modern” correctional facilities, leading scholar William Nagel well summarized the response and the dilemma: “To avoid a federal Attica, the Federal Bureau of Prisons is now feverishly attempting to recruit black staff, but its task is complicated by the remoteness of its facilities.”

By 1995, the latest year with complete data, the prisoner population at Attica had increased to 80 percent black and Latino. But out of a total staff of 854, the number of blacks had only risen to 21 and the Latino staff to 7. Attica’s staff remains 96.7 percent white because Attica itself has not moved. It remains in a rural, overwhelmingly white region in New York State.

While prisons themselves are impossible to move, this lesson of Attica about the dangers of prisoner-staff disparities has been lost in the rush of the late 1980s and 1990s to build more prisons. Speculative ideas about rural economic development have trumped safe and rehabilitative correctional policy. Two-thirds of new prisons have been built in rural areas despite the experience at Attica and despite the research showing that incarcerating a prisoner close to home aids family visits and helps reduce the odds a prisoner will re-offend and be returned to prison.

Prior to 1980, 36 percent of prisons were in rural areas, although only 20% of the country is rural. But by the early 1990s the trend was going the wrong way, with 60 percent of new prisons being built in rural areas.

Senior federal officials explained the results to Nagel in 1973: “In the rural areas you get the very best type of white, mid-American line staff; but it is admittedly more difficult to recruit blacks and professional staff which are available in the cities.”

Has the federal Bureau of Prisons or state departments of correction succeeded in overcoming the difficulties in attracting black staff to rural prisons? According to our analysis of prison staffing at each prison operating in 1995, the answer is no.

In 1995, there were 889 federal and state prisons with at least 100 black prisoners. After excluding a handful that did not provide the race of prisoners or staff, we were able to identify only 64 prisons where the percentage of staff that were black was at least as high as the percentage of the prisoners that were black. Of those prisons, not one was outside of the south or the urban cities of the north.

Half of the prison cells in this country are filled with black citizens, but only 20 percent of the prison jobs are held by black employees. In the eyes of the American justice system, it appears every race still has its separate place.

Peter Wagner is a Soros Justice Fellow at the Prison Reform Advocacy Center in Cincinnati, Ohio. Rose Heyer is an independent researcher in Massachusetts.

Johnny Cash consistently identified with the downtrodden and recorded a number of songs about the hopeless misery of imprisonment.

by Peter Wagner,

September 12, 2003

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall and may I live to tell.

May all the world forget you ever stood.

And the whole world will regret you did no good.

–Johnny Cash, “San Quentin” 1969

In Memory of Johnny Cash

February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003

September 12, 2003 — The Man in Black, country music star Johnny Cash, died today at age 71. Although Johnny only spent one day in jail himself, he consistently identified with the downtrodden, eagerly performing a number of free concerts for prisoners. Two of these concerts became popular albums Live at San Quentin and Live at Folsom Prison. He was best known for Folsom Prison Blues, about the endless loneliness faced by a reformed man in prison:

I hear the train a-comin’

It’s rollin’ round the bend.

And I ain’t seen the sunshine

Since I don’t know when.

I’m stuck in Folsom Prison

And time keeps draggin’ on.

Johnny wrote or recorded a number of songs about the hopeless misery of imprisonment including Send a picture of Mother, The Wall, The walls of a prison, There ain’t no good chain gang, I got stripes, (I heard that) lonesome whistle, Green, Green Grass of Home, Give my love to Rose, Jacob Green, Austin Prison, Orleans Parish Prison, and a number of songs authored by prisoners present at his performances, including I don’t know where I’m bound.

In memory of the Man in Black, his work, and his music, it seemed appropriate to highlight two of his lesser known songs: “Man in Black” and “San Quentin”.

We’ll miss you Johnny. May all the world never forget you sang. All the world will rejoice you did so much good.

Man In Black

Well, you wonder why I always dress in black,

Why you never see bright colors on my back,

And why does my appearance seem to have a somber tone.

Well, there’s a reason for the things that I have on.

I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down,

Livin’ in the hopeless, hungry side of town,

I wear it for the prisoner who has long paid for his crime,

But is there because he’s a victim of the times.

I wear the black for those who never read,

Or listened to the words that Jesus said,

About the road to happiness through love and charity,

Why, you’d think He’s talking straight to you and me.

Well, we’re doin’ mighty fine, I do suppose,

In our streak of lightnin’ cars and fancy clothes,

But just so we’re reminded of the ones who are held back,

Up front there ought ‘a be a Man In Black.

I wear it for the sick and lonely old,

For the reckless ones whose bad trip left them cold,

I wear the black in mournin’ for the lives that could have been,

Each week we lose a hundred fine young men.

And, I wear it for the thousands who have died,

Believen’ that the Lord was on their side,

I wear it for another hundred thousand who have died,

Believen’ that we all were on their side.

Well, there’s things that never will be right I know,

And things need changin’ everywhere you go,

But ’til we start to make a move to make a few things right,

You’ll never see me wear a suit of white.

Ah, I’d love to wear a rainbow every day,

And tell the world that everything’s OK,

But I’ll try to carry off a little darkness on my back,

‘Till things are brighter, I’m the Man In Black

San Quentin

An’ I was thinkin’ about you guys yesterday. Now, I been here three times before, an’ I think I understand a little bit about how you think about some things, it’s none of my business how you feel about some other things and I don’t give a damn how you feel about some other things! But anyway, I tried to put myself in your place, and I believe this is the way that I would feel about San Quentin.

San Quentin, you’ve been livin’ hell to me.

You’ve galled at me since nineteen sixty three.

I’ve seen ’em come and go and I’ve seen them die,

And long ago I stopped askin’ why.

San Quentin, I hate ev’ry inch of you.

You’ve cut me and you’ve scarred me through an’ through.

And I’ll walk out a wiser, weaker man;

Mr Congressman, why can’t you understand?

San Quentin, what good do you think you do?

Do you think that I’ll be different when you’re through?

You bend my heart and mind and you warp my soul,

Your stone walls turn my blood a little cold.

San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell.

May your walls fall and may I live to tell.

May all the world forget you ever stood.

And the whole world will regret you did no good.

San Quentin, you’ve been livin’ hell to me.

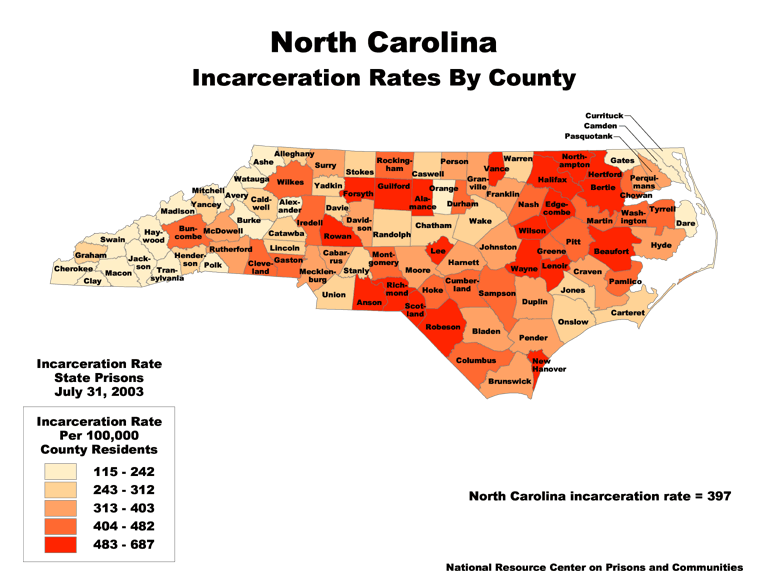

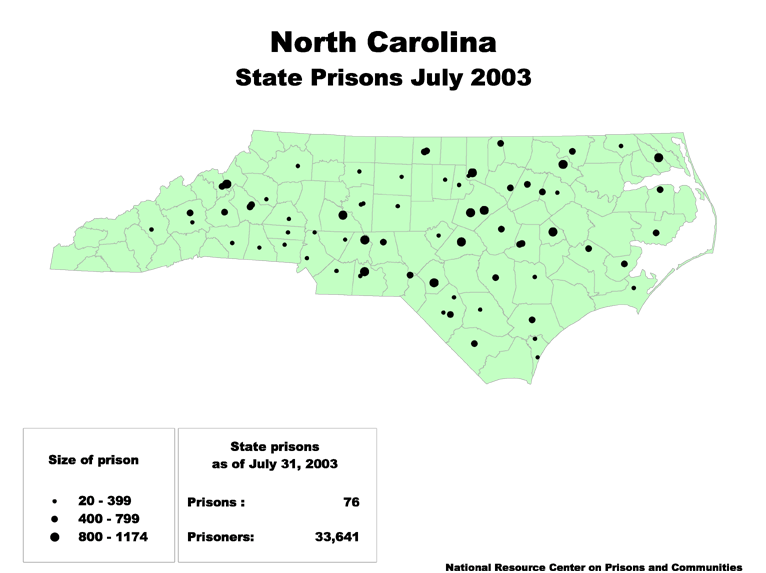

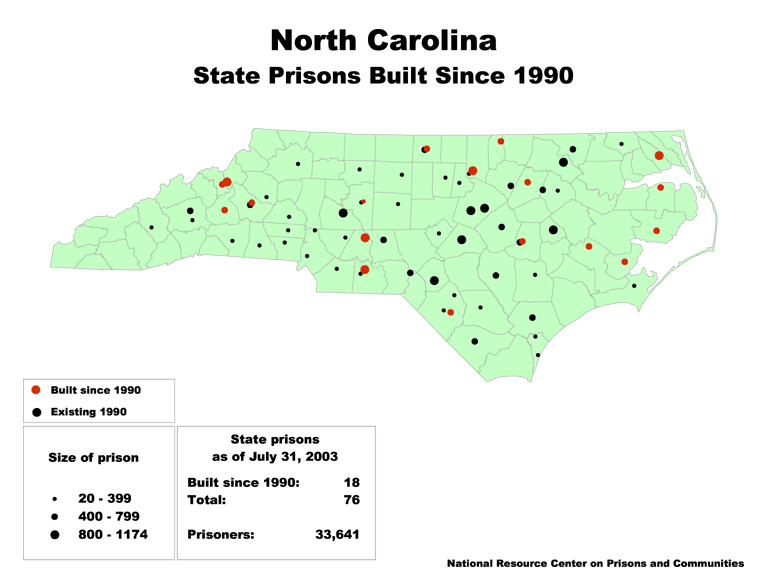

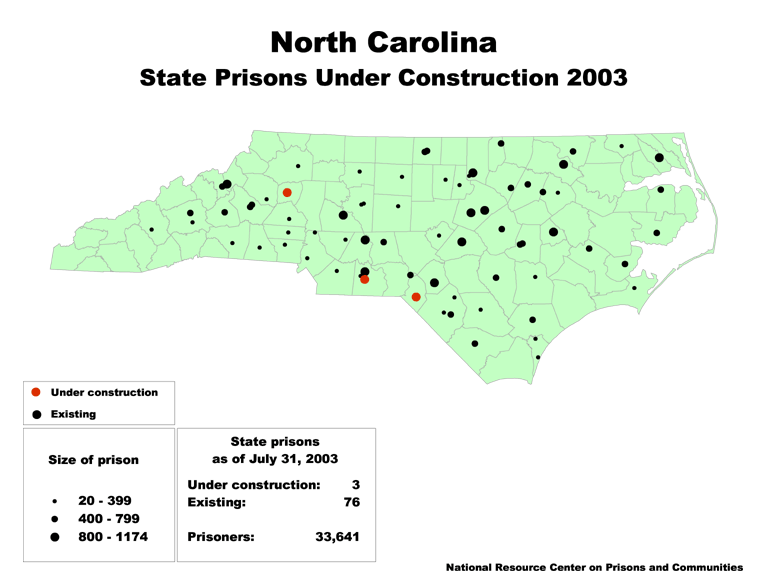

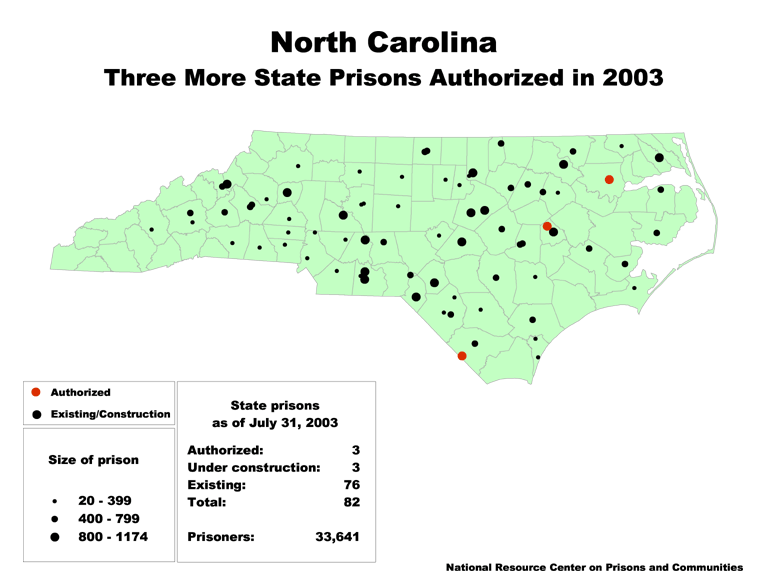

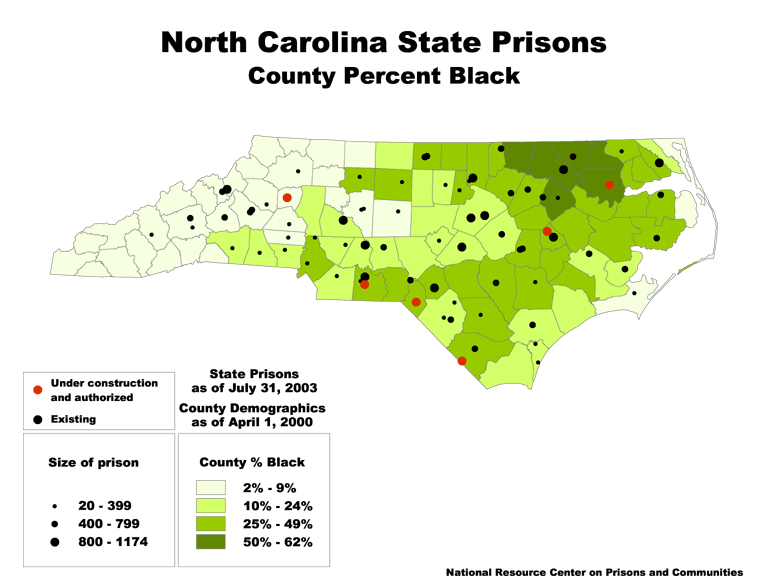

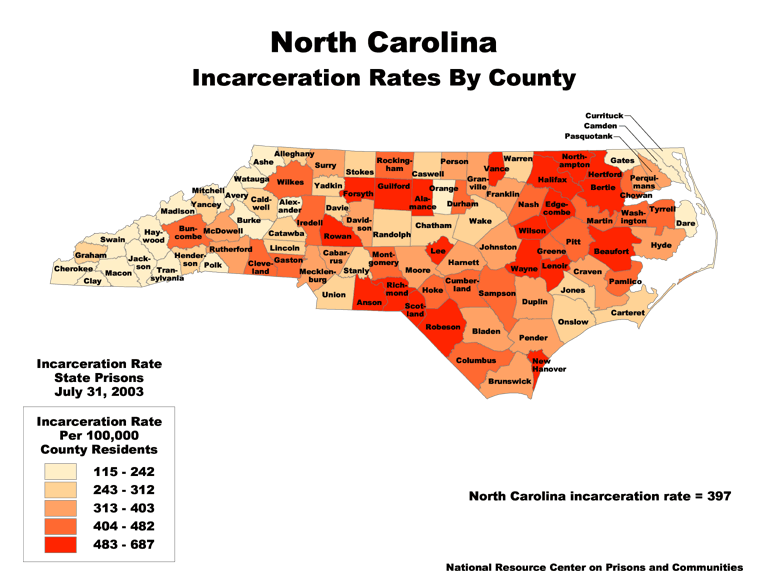

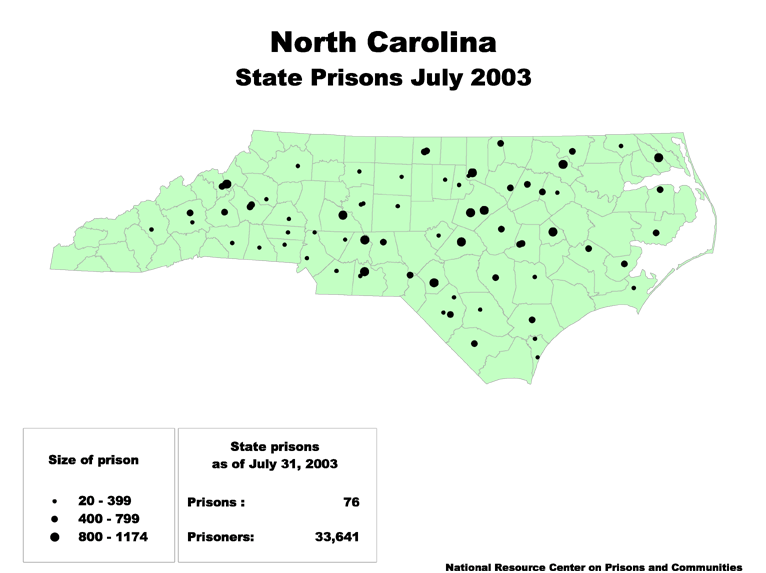

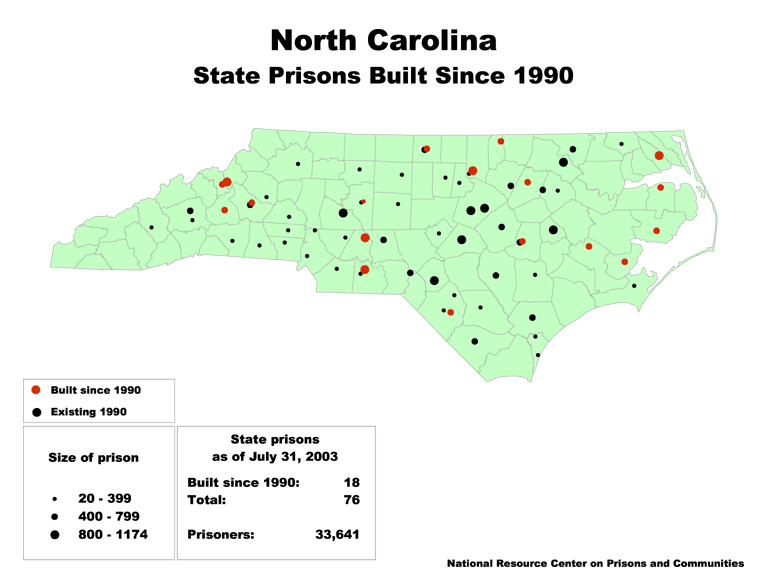

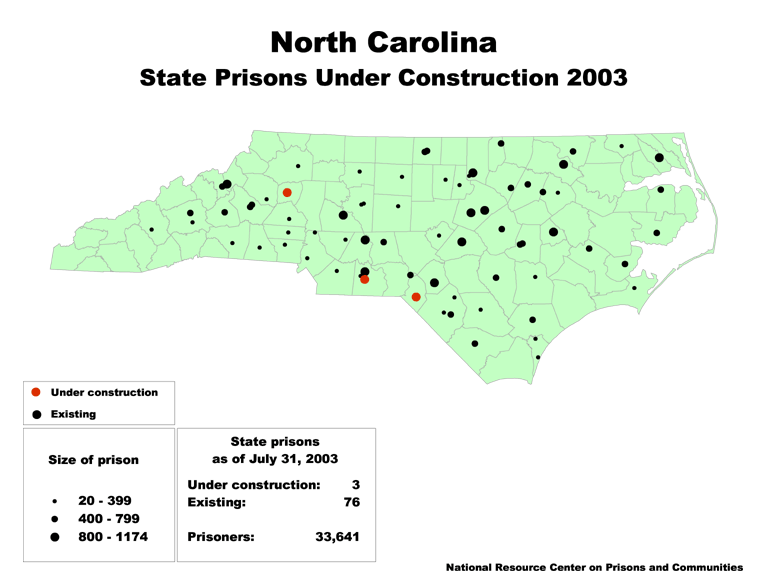

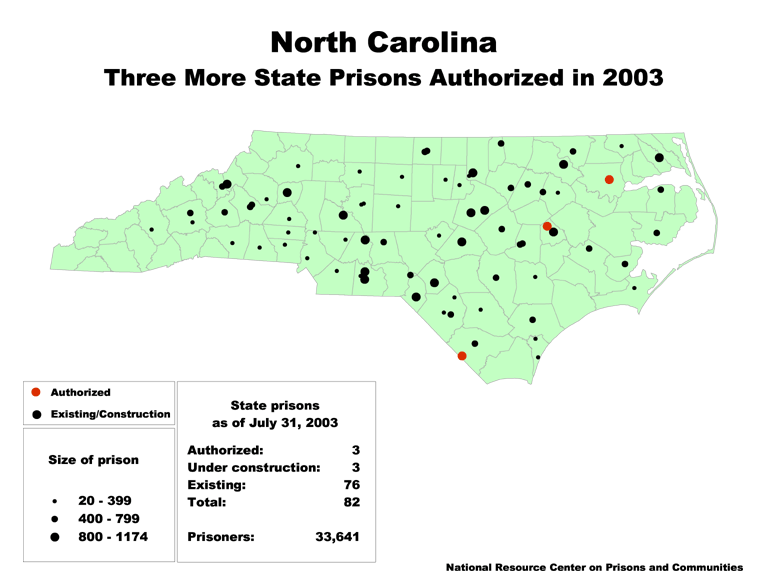

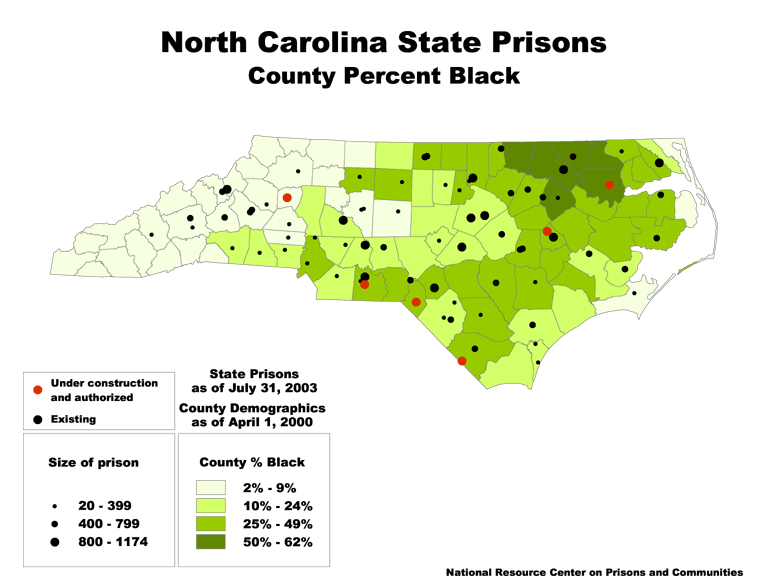

A series of maps of North Carolina showing incarceration rates and prison expansion over time by county.

by Rose Heyer,

September 1, 2003

These maps were prepared for the National Resource Center on Prisons and Communities, September 2003.

New documentary explores the historically taboo subject of homosexual relations and rape in prison.

by Peter Wagner,

July 3, 2003

New documentary: Turned Out: Sexual Assault Behind Bars

Of the over two million Americans in jail today, one out of five inmates will be sexually assaulted during their incarceration. Most of those who will be “turned out,” or sodomized, and turned into sexual slaves, will be nonviolent drug offenders who have doubled the prison population over the last decade. This video is a shocking but insightful expose of the taboo subject of homosexual rape and homosexual relations in prison. It features frank and often graphic interviews with inmates at correctional facilities throughout the U.S., in which they explain the sexual hierarchy of “iboys” or “sissies,” who play the female role to more powerful inmates known as “men,” with the latter often developing relationships with several “boys” and thus developing “families,” which provide sex, companionship and protection for more vulnerable inmates. Prisoners also discuss the underground economy, the sociology of power and lust, and the sexual exploitation of inmates by prison guards, while interviews with a prison warden and family members of inmates reveal the general awareness of sexual assault within our prison system and the culture of silence which enables its perpetuation.

It’s expensive ($295 to buy, $95 to rent), but we don’t know of anything that comes even close to this on this topic.

[Editor’s note, July 10, 2014: full film is now available here.]

The 1976 handbook to prison abolition has been digitized.

by Peter Wagner,

May 22, 2003

Instead of Prisons: A Handbook for Prison Abolitionists is now available on this website. This book summarizes the research on prisons as of the 1976 writing and discusses the strategy of abolition. For example, how do we pick reforms to fight for now that make our long term goal of abolition easier to obtain?

Thanks to everyone who helped with the digitization process!

Nil's Christie's book on the criminal justice "pain delivery system" has been digitized.

by Peter Wagner,

February 12, 2003

We can’t speak highly enough of Nils Christie’s Crime Control as Industry (review, buy from Amazon.com). Christie’s first book, Limits to Pain (1981), which argues that the criminal justice system is in fact a pain delivery system, with the size of the system controlled not by the number of committed acts labeled as crimes but by the amount of pain that a society is willing to impose on its citizens, is now available on the internet. Limits to Pain is powerful in its own right, and very helpful in studying the most recent book. We suggest you read the on-line version of Limits to Pain today.