On Saturday, I was honored to accept, on behalf of the Prison Policy Initiative, the Foundation for Improvement of Justice's Paul H. Chapman Award for our report and campaign to end Massachusetts' suspension of drivers licenses for unrelated drug offenses.

by Peter Wagner,

September 30, 2016

On Saturday, I was honored to accept, on behalf of the Prison Policy Initiative, the Foundation for Improvement of Justice’s Paul H. Chapman Award.

The Atlanta-based foundation recognized the Prison Policy Initiative for our report Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving. This report exposed a little-known, but extremely harmful, law that automatically suspended driver’s licenses for drug offenses, regardless of whether the offenses involved driving or road safety. The state would then charge $500 for reinstatement, further ensuring that people with drug convictions would have a hard time getting employment or fulfilling familial needs.

The Atlanta-based foundation recognized the Prison Policy Initiative for our report Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving. This report exposed a little-known, but extremely harmful, law that automatically suspended driver’s licenses for drug offenses, regardless of whether the offenses involved driving or road safety. The state would then charge $500 for reinstatement, further ensuring that people with drug convictions would have a hard time getting employment or fulfilling familial needs.

Our report provided persuasive evidence of the law’s failure as a crime deterrent, pointed out that the law actually made the roads less safe because it increased the number of unlicensed and uninsured drivers, and included a detailed analysis of the resources wasted on enforcing unnecessary license suspensions.

Our followup advocacy helped the state understand that the law was punishing entire communities, not just a few individuals; and the law was repealed earlier this year.

Thirteen other states and the District of Columbia have similar laws, so we will be using the prize money to expand our campaign for reform of this outdated relic of the War on Drugs.

Below are some pictures of the award ceremony.

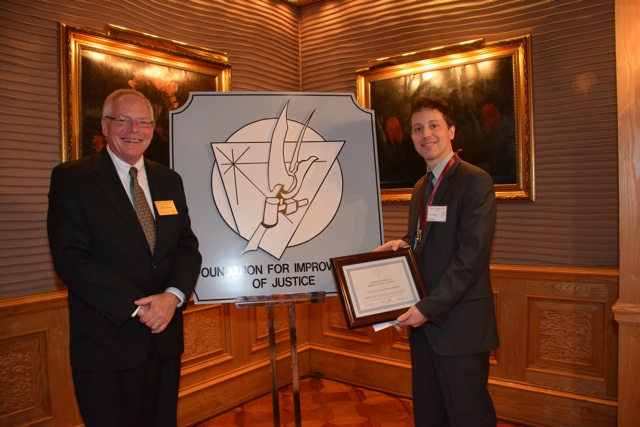

Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

by Joshua Aiken,

September 30, 2016

While comprehensive criminal justice reform for adults has failed to pass in Congress, a bill lingering in the Senate could still overhaul how our juvenile justice system works. The bipartisan legislation, which passed the House by an overwhelming 382-29 vote, would create several new policies that juvenile justice advocates have been requesting for years.

The proposed reauthorization of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act would withhold funding from states that put youth in adult prisons, require states to collect data on racial disparities in the juvenile justice system, ban the practice of shackling pregnant girls, and prohibit states from locking up youth for “status offenses.”

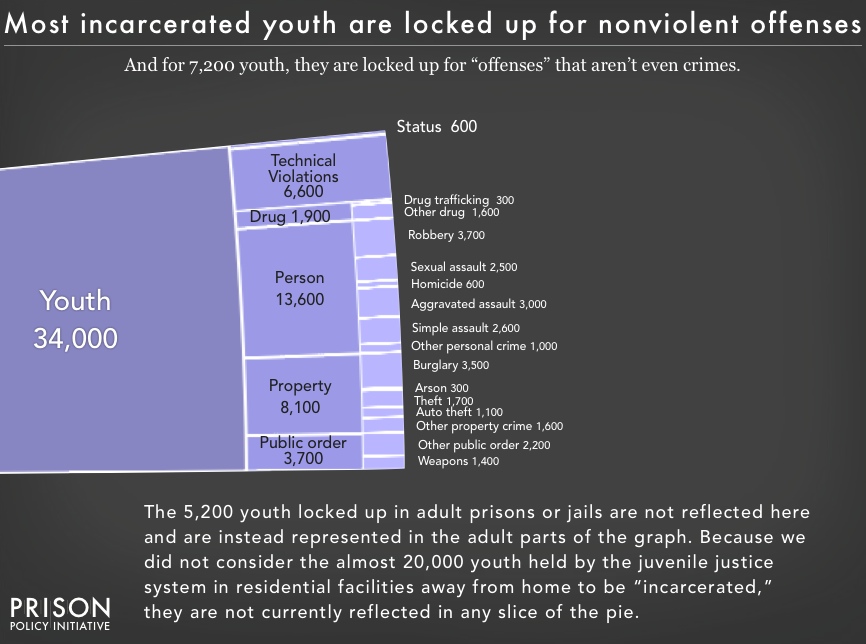

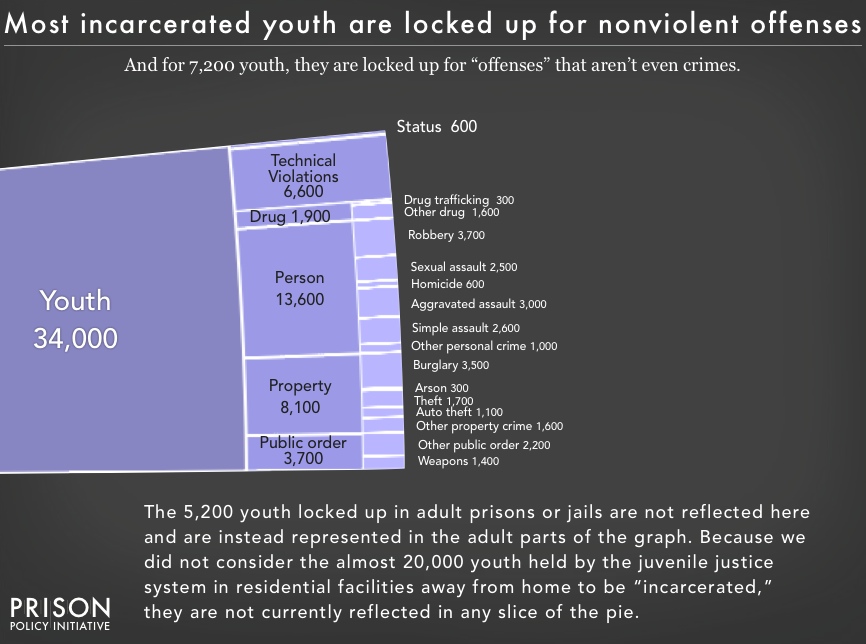

These reforms are desperately needed. In our 2016 report, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie we highlighted one of the most disturbing facets of our juvenile justice system: that we lock young people up for behaviors that are not law violations for adults—like running away or skipping school.

Talking about “status offenses” is important because status offenses aren’t even crimes. These offenses relate to a person’s age: skipping school, breaking curfew, or even talking back can land a young person behind bars. Increasingly, those young people are girls.

In an incredible piece for Mother Jones last week, Hannah Levintova details how bias and over-criminalization are ensnaring more and more girls into the criminal justice system. Levintova explains:

Between 1995 and 2009, cases of breaking curfew rose by 23 percent for girls—and just 1 percent for boys. In 2011, girls made up 53 percent of runaway cases brought before a judge. Between 1996 and 2005, arrests for “simple assault”—which could be as minor as a daughter throwing a toy at her mom—went up 24 percent for girls and down 4 percent for boys. By 2013, girls were almost twice as likely as boys to be in detention for simple assault and certain other nonviolent offenses.

Girls, argues Professor Andrew Spivak, are faced with types of “judicial paternalism” where “courts think that they need to protect girls and give them guidance.” Professor Stacy Mallicoat, in a 2007 study, showed that probation officers often attribute girls’ offending behaviors to their sexual behavior, drug use, and negative family relationships. Girls, and especially girls of color, get blamed. Meanwhile, when describing boys, probation officers were less likely to see their criminal behaviors as coming from these sources. As Levintova puts it, the justice system sees boy’s behaviors as “lifestyle choices” while the morals of girls are punished.

The disparate prosecution of status offenses sheds light on the deeply gendered ways our criminal justice works. And these offenses end up having a disastrous and long-lasting impact on girls:

Even a brief period in detention can lead to mental and

physical health issues, higher unemployment rates, lower lifetime

earnings, and substance abuse. The moral judgment that underlies the charges girls face can also change how they see themselves. “Once they internalize that they are ‘bad girls,'” says [Jeannette] Pai-Espinosa, “it almost creates a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The bill’s sponsors in the House are hopeful that the legislation can reach President Obama’s desk, but some legislators are strongly opposed.

The Massachusetts prisons system wants to make it harder to visit and harder to mail materials to incarcerated people. We tell them that's a bad idea.

by Joshua Aiken,

September 28, 2016

Incarcerated people and their families are more likely to succeed if they are allowed and encouraged to remain in touch.

Unfortunately, the Massachusetts Department of Corrections is proposing new regulations that will make it harder for families to stay in touch. The proposed amendments would restrict the number of people allowed on a pre-approved visitation list, subject private attorneys’ correspondence with their incarcerated clients to unconstitutional review, and limit incarcerated peoples’ ability to receive more than five pages a day of photocopied material.

Tomorrow, at a public hearing, the Department will be taking comments on these and other proposed amendments to the Code of Massachusetts Regulations. Today, I submitted two letters on behalf of the Prison Policy Initiative addressing these counterproductive proposals.

My letters make the case that:

- The Department of Corrections should encourage, not discourage, written communication from loved ones.

- Forcing incarcerated people to choose which members of their families and which of their friends can visit them isn’t just unnecessary. It’s wrong.

Bill Newman takes on injustice 90 seconds at a time. In the newest episode of his Civil Liberties Minute podcast, he takes on the practice of locking up poor people because they can't afford bail.

by Peter Wagner,

September 27, 2016

Friend of the Prison Policy Initiative Bill Newman has again featured our research in his Civil Liberties Minute podcast produced with the ACLU. This time he takes on the epidemic of jailing the innocent before trial in a powerful 90 second explainer.

You can listen or subscribe on iTunes and the transcript with some links to some of the source material is below.

Thank you, Bill!

In Jail And Innocent

Why is your mother, father, sister, brother, lover or friend, who is presumed innocent, still locked up in jail?

Know this: he or she is not alone. Of the 664,000 people locked up in local jails today, 70% of them have not been convicted or sentenced for any crime. Really – 70% are locked up only because they can’t make bail.

In the past 15 years 99% of the growth in the jail population comes from people who don’t have the 50 or 100 or 250 or 400 dollars to get bailed out. When the person held on bail finally goes to court he will be offered a deal. Plead guilty and you can get out, time served, go home today. Or you can say you’re innocent and want a trial, and stay locked up for days, weeks, months, or years. What would you do?

The Eighth Amendment to The Constitution in theory guarantees a reasonable bail and bail in theory is only supposed to be used to help insure the attendance of the defendant at trial – not as a subterfuge for pre-trial detention.

But as the numbers and the lives ruined prove, the constitutional principles of reasonable bail and innocent until proven guilty really only applies to those who are economically well off enough to make their bail.

The United States is the only country in the world that sentences people under 18 to die behind bars. Which states do it, and why?

by Joshua Aiken,

September 15, 2016

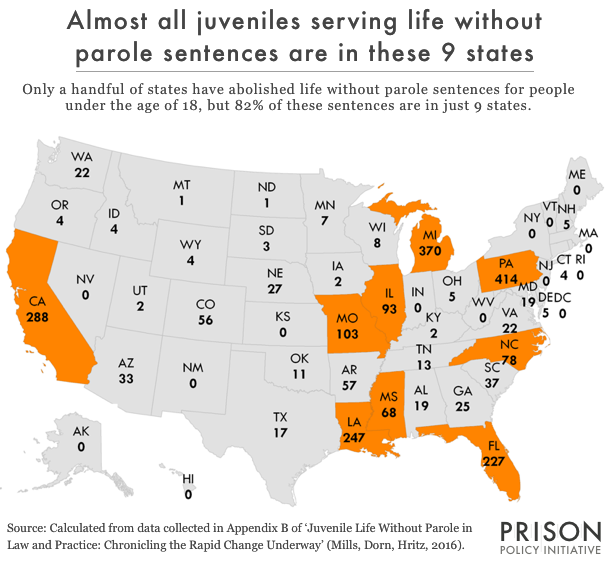

The United States is the only country in the world that sentences people under 18 to die behind bars. The Supreme Court has twice declared many of these sentences to be unconstitutional, but some states are resisting the Court’s required reforms. (In 2012, the Court struck down mandatory juvenile life without parole sentences. Earlier this year, the Court made that decision retroactive.)

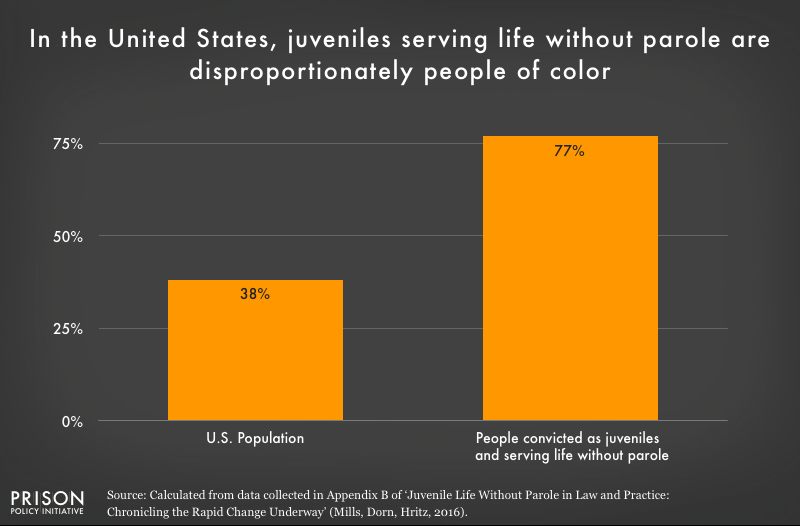

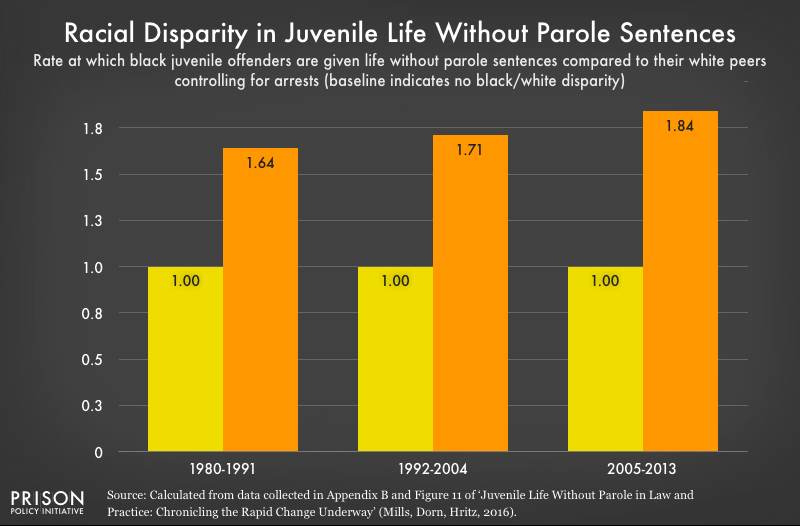

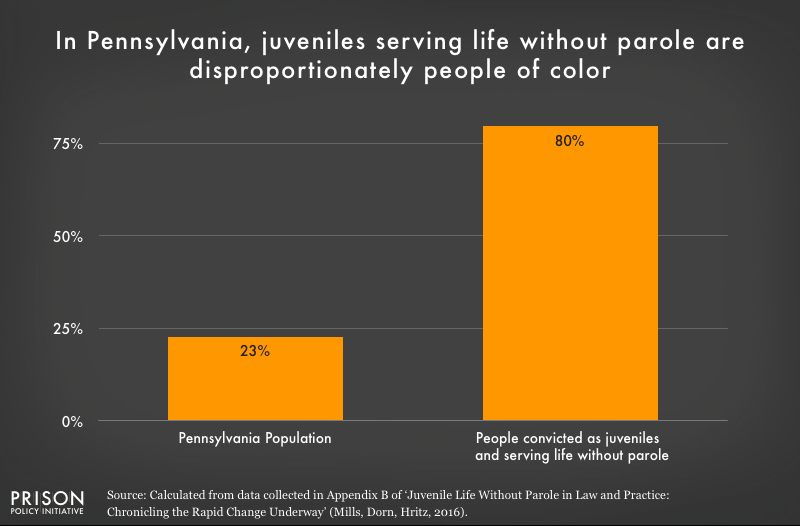

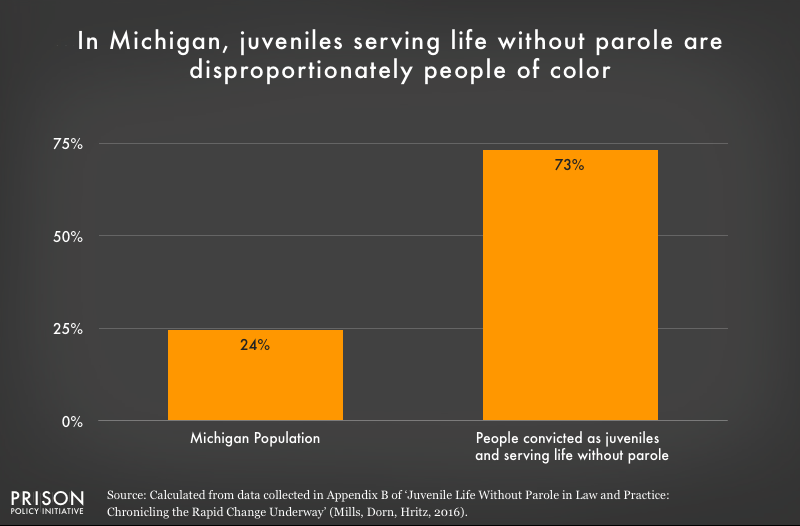

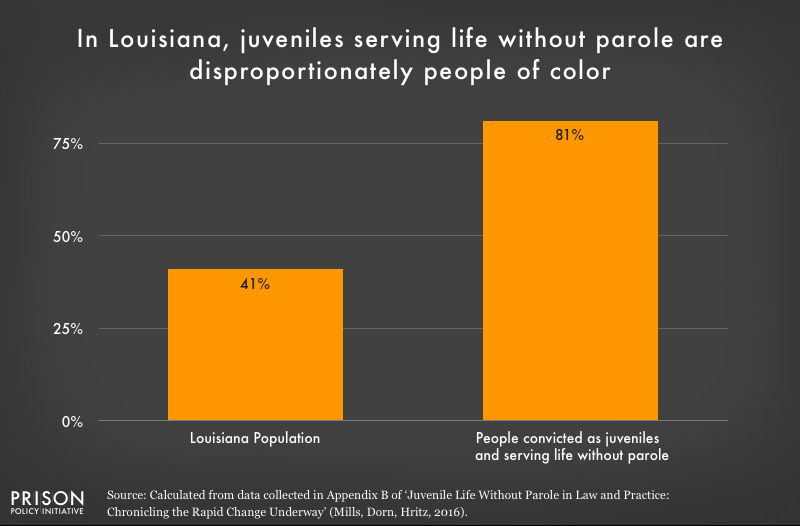

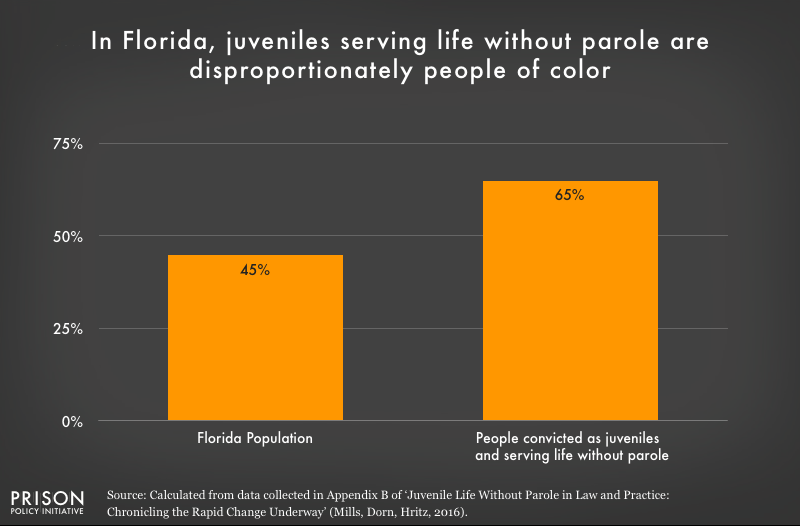

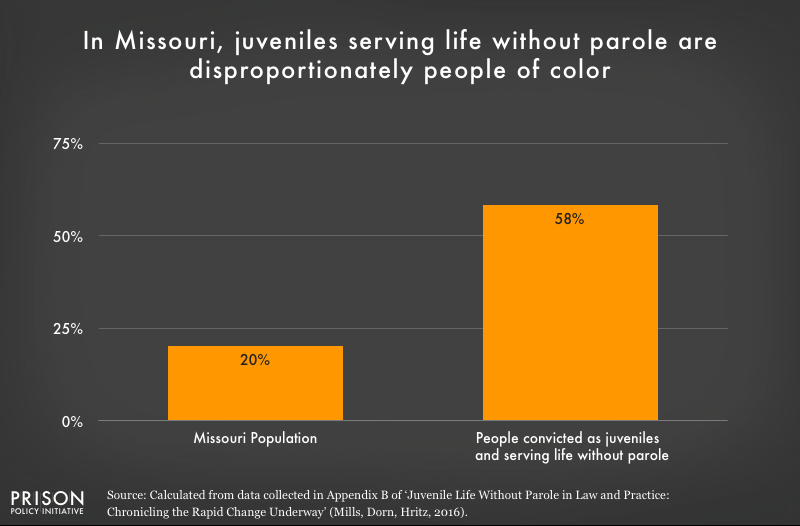

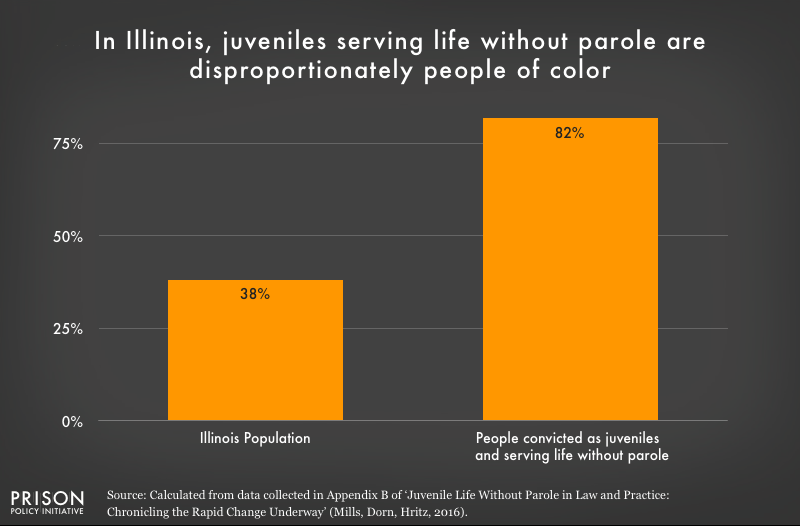

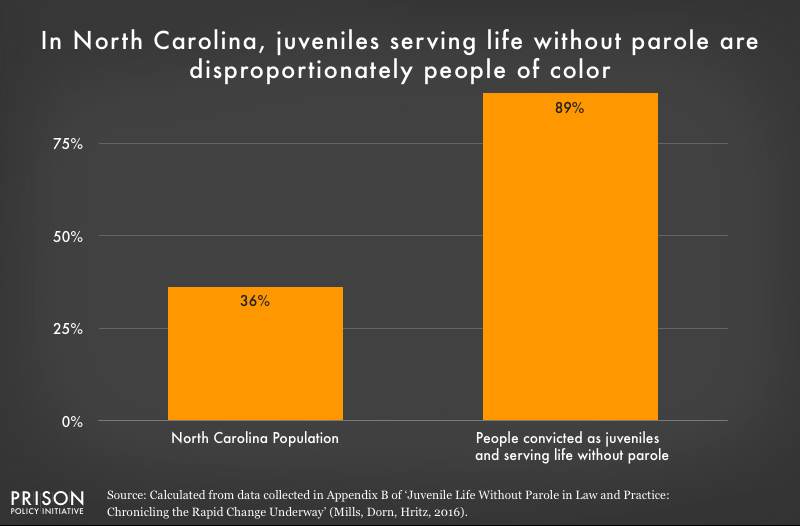

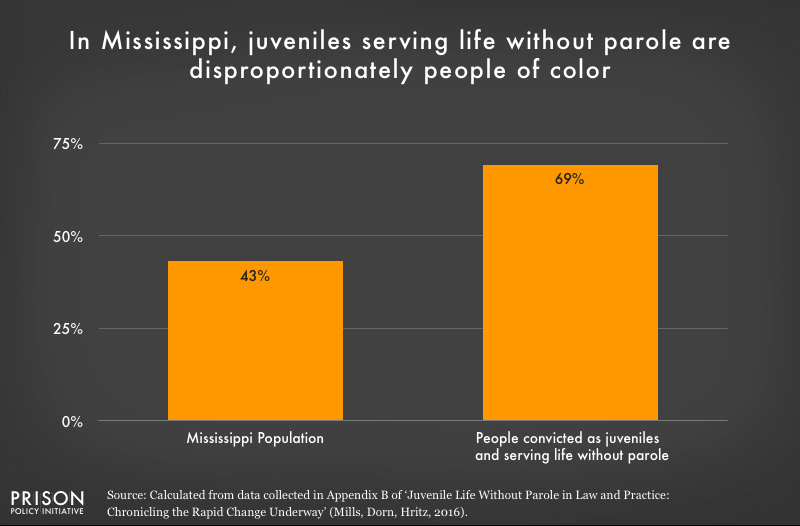

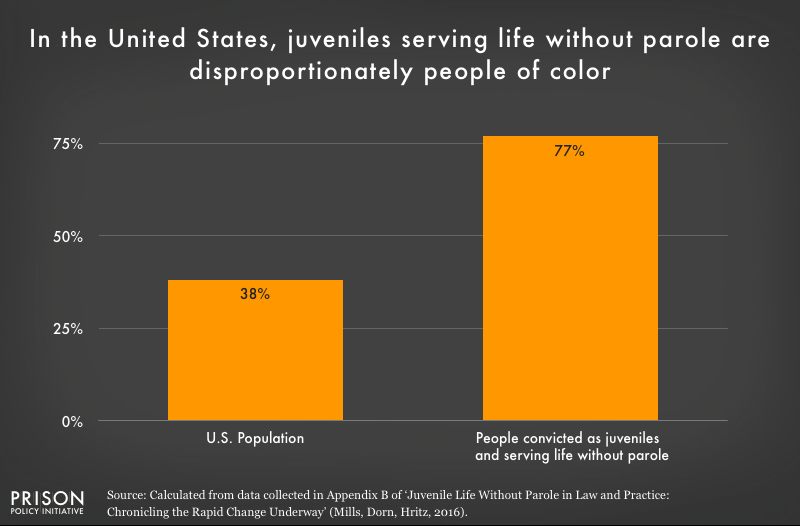

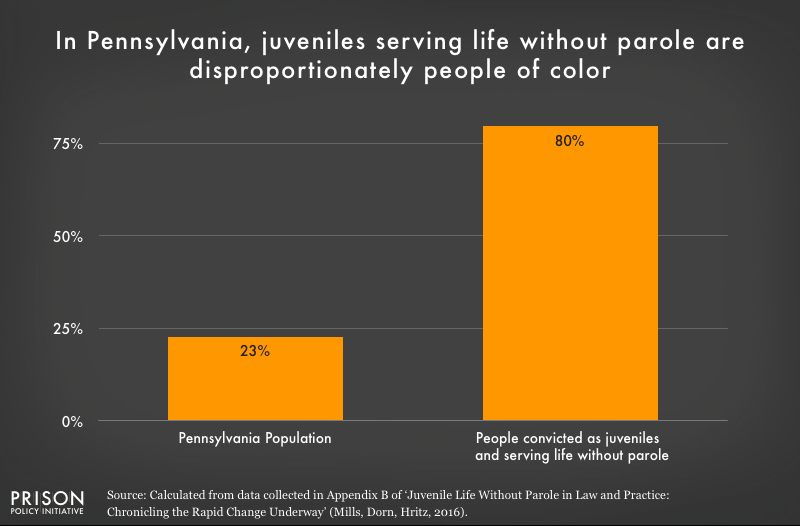

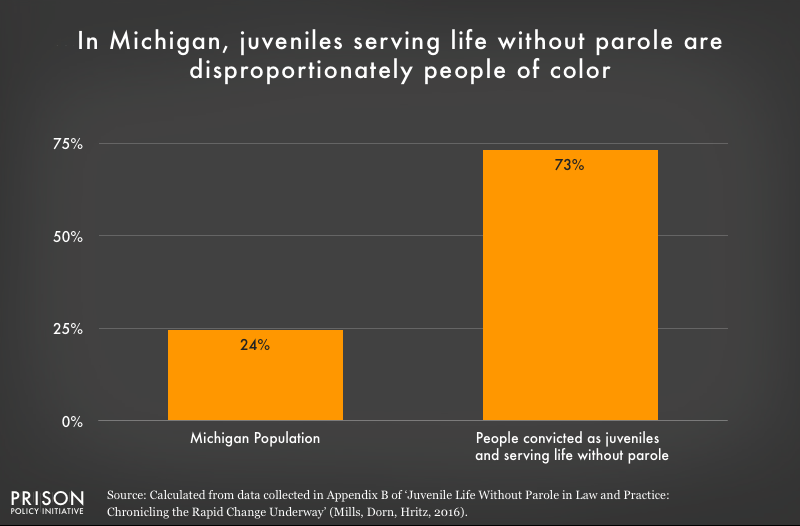

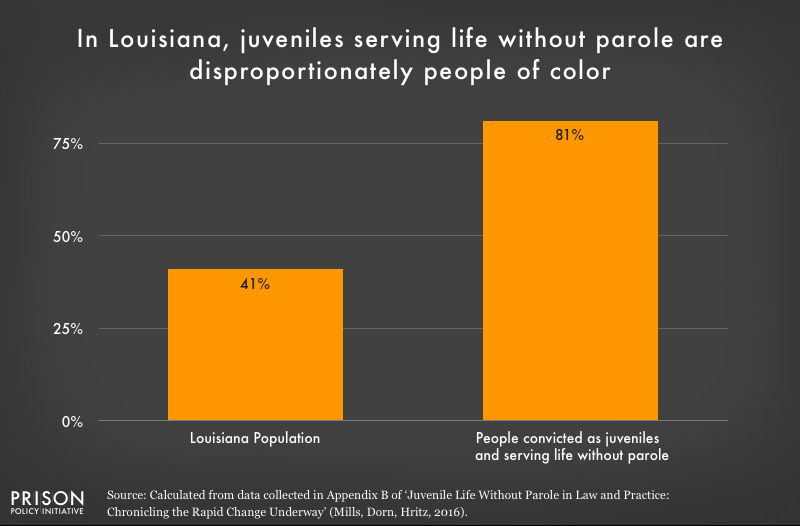

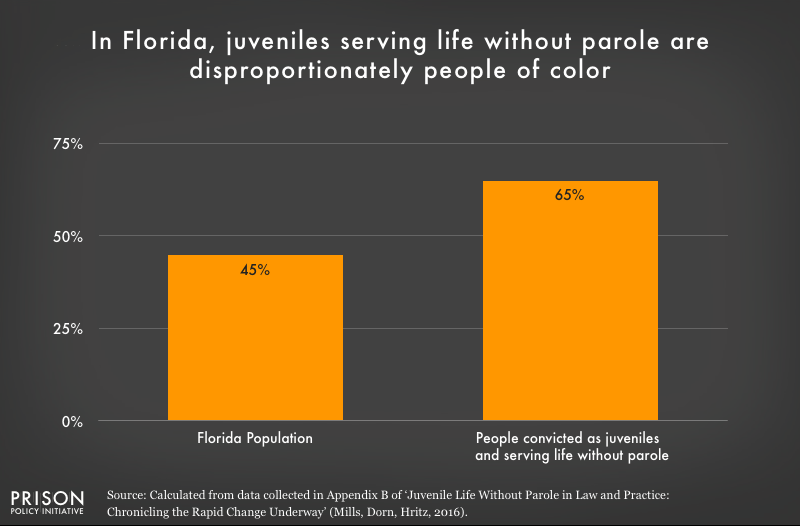

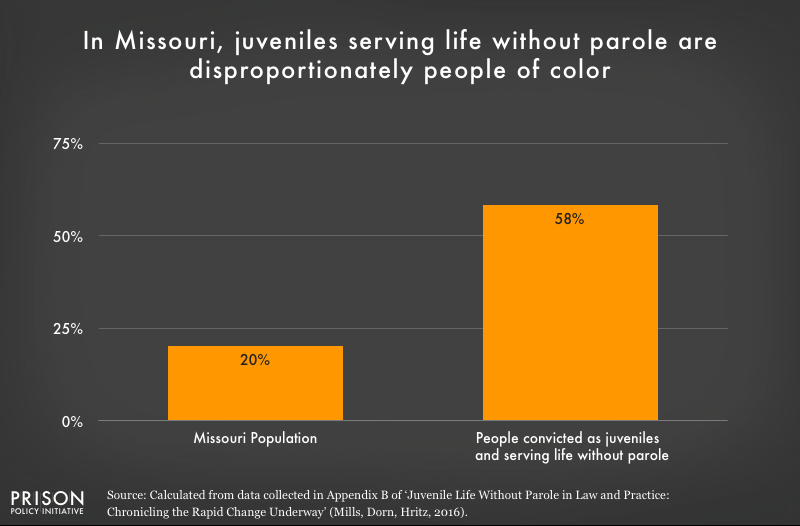

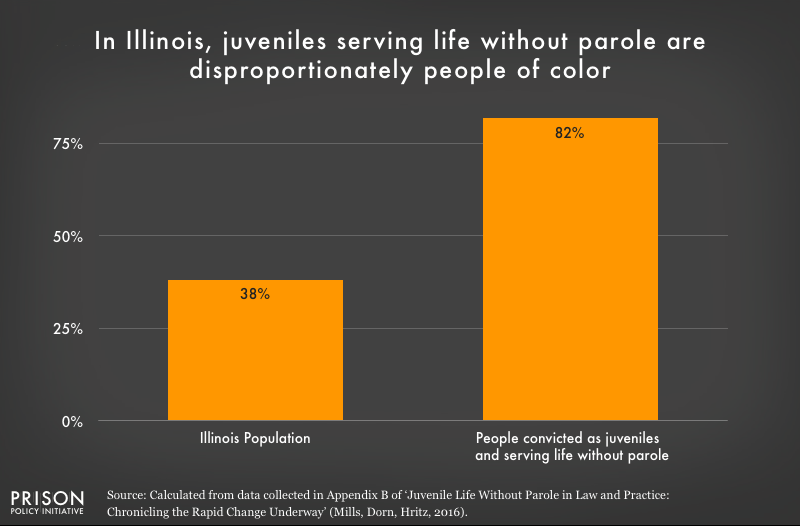

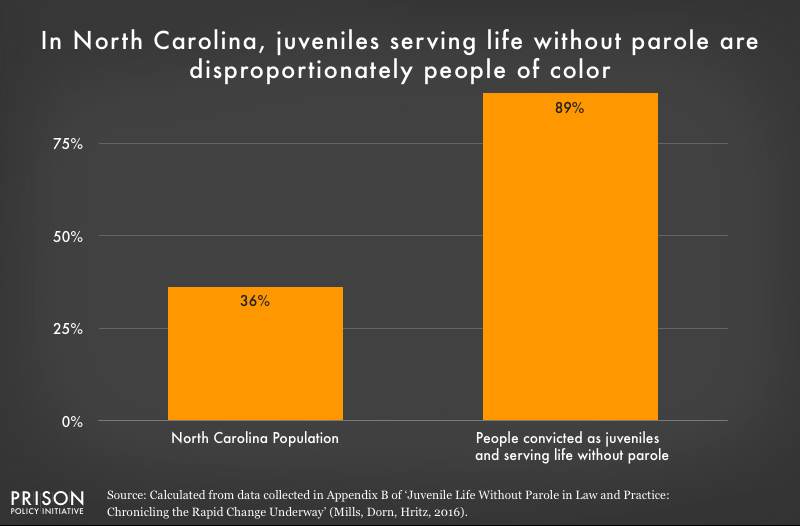

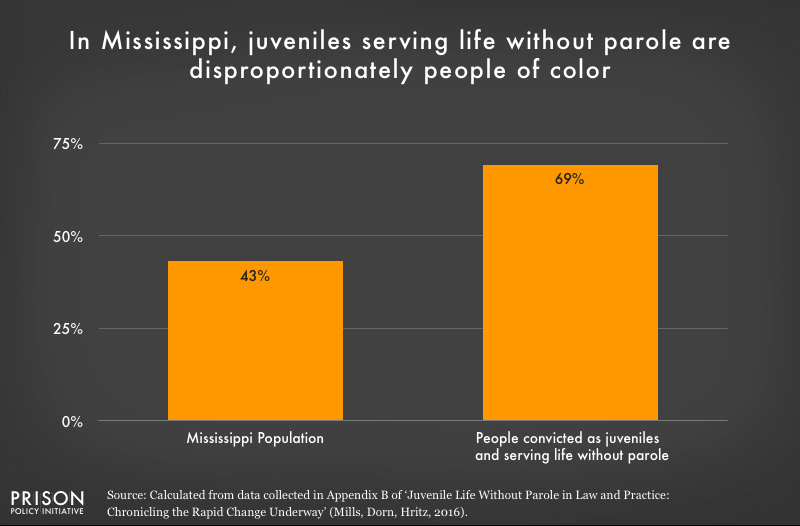

While a number of states continue to use life without parole sentences for juveniles, new research shows that those juveniles are largely and increasingly people of color. A recent study by researchers from the Phillips Black Project found that people of color are overrepresented in the juvenile life without parole population “in ways perhaps unseen in any other aspect of our criminal justice system.”

Young black people are hit hardest by prosecutors’ punitive approach. This is unsurprising. Black children are more likely to be punished by their teachers for the same behaviors, are 2.3x more likely to be referred to law enforcement by school officials, and 3x more likely to be suspended or expelled than their white peers.

Being sentenced to die behind bars, however, is especially egregious. The Phillips Black Project found that black youth are twice as likely to receive a juvenile life without parole sentence compared to their white peers for committing the same crime.

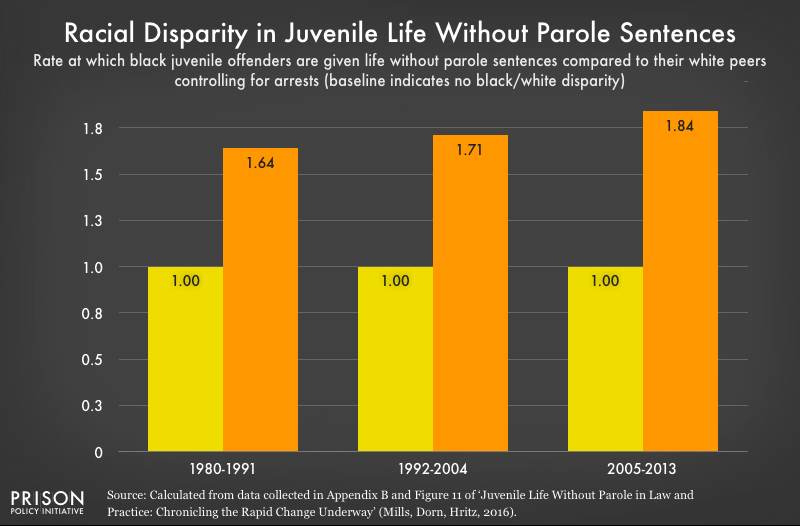

Significantly, the researchers found that racial bias exists in the prosecutorial and judicial phases of the criminal justice system. Controlling for the fact that black youth have more encounters with the police, this study compared the number of black and white juveniles life without parole sentences against the number of relevant arrests.

By focusing only on the disparate outcomes that occur after the moment of arrest, the Philips Black Project researchers call attention to how prosecutors and courts fail to fairly determine guilt, innocence and punishment.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.

This finding gives new urgency to the 2014 findings of psychologists in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that black youth are generally less likely to be seen as innocent and more likely to be perceived as adults. This result was particularly strong when black youth were accused of a serious crime.

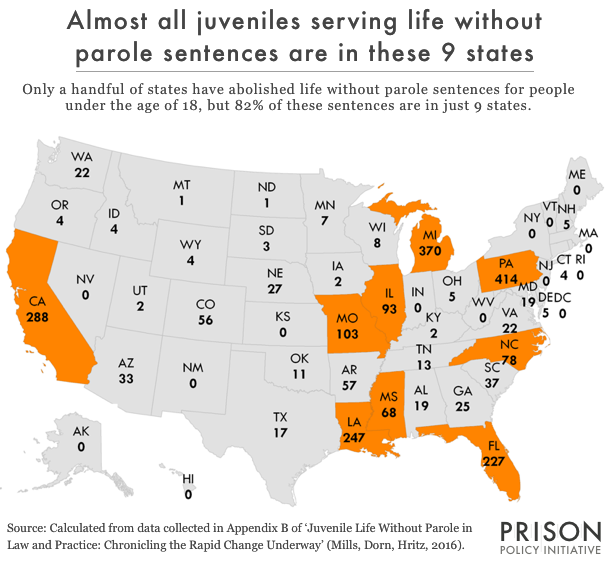

The good news is that juvenile life without parole sentences are falling out of favor; at least eighteen states have abolished the sentence altogether. Sadly, there are a handful of states that have steadfastly held onto the punishment. Just nine states account for four out of every five cases.

Legislators in these states have been remarkably resistant to reform. Take Louisiana for instance. This June, after passing the House with a resounding 83-2 vote, a Senator filibustered the bill with just ten minutes left in the legislative session. For the thousands serving these sentences, the next legislative session, and a chance at a second chance, can’t come soon enough.

Juvenile life without parole sentences are not only irredeemably harsh but are also indicative of the racial biases ingrained in our criminal justice system. Below I’ve put together graphs showing just how overrepresented people of color are in eight of the nine states responsible for the vast majority of juvenile life without parole cases. (California does not provide data on the race and gender of its juvenile life without parole population.)

Note: In order to calculate the national and state-level people of color population, I used 2015 U.S. Census data as to match the data collection period of the Mills, Dorn, Hritz study. Additionally, my use of people of color is based on analyzing Census data for all respondents who do not identify as ‘Non-Hispanic White.’

Prison Policy Initiative is looking for a new Policy & Communications Associate!

by Alison Walsh,

September 9, 2016

Are you interested in joining our dedicated team to produce cutting edge research to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization? Do you want to shape innovative advocacy campaigns and spark critical discourse to create a more just society?

If so, consider our Policy & Communications Associate (link no longer available) position.

Please spread the word!

More and more people are talking about an uptick in murder and crime. Is there cause for alarm? No.

by Wendy Sawyer,

September 8, 2016

More and more people are talking about an uptick in murder and crime. Is there cause for alarm?

No.

While murder is up in some cities, and in cities like Chicago significantly, there isn’t a crime wave and it’s certainly not being caused by the proliferation of citizens recording the police.

Looked at historically, murder is much less common than it used to be; and the small increase from 2014 to 2015 resembles the usual annual fluctuations. This minor change does not justify FBI Director James Comey’s declaration, “Holy cow do we have a problem” or Donald Trump’s tweet that “inner city crime is reaching record levels.”

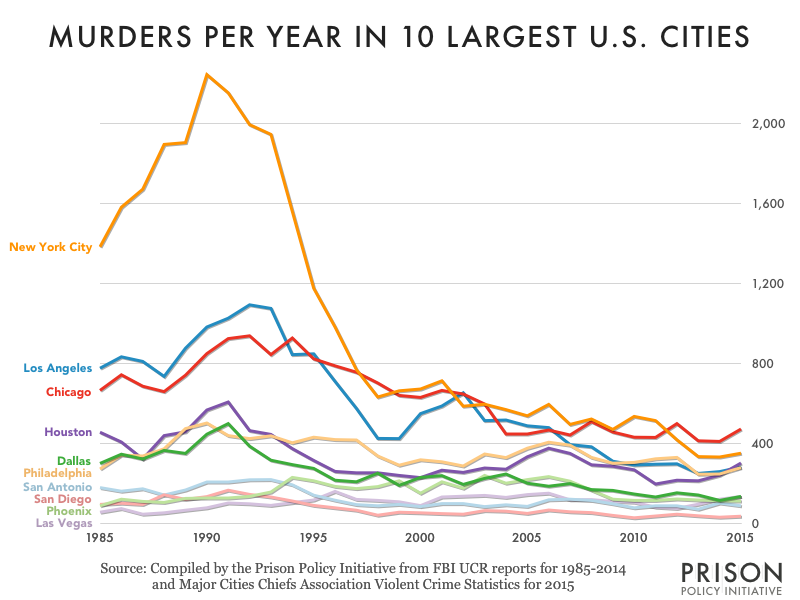

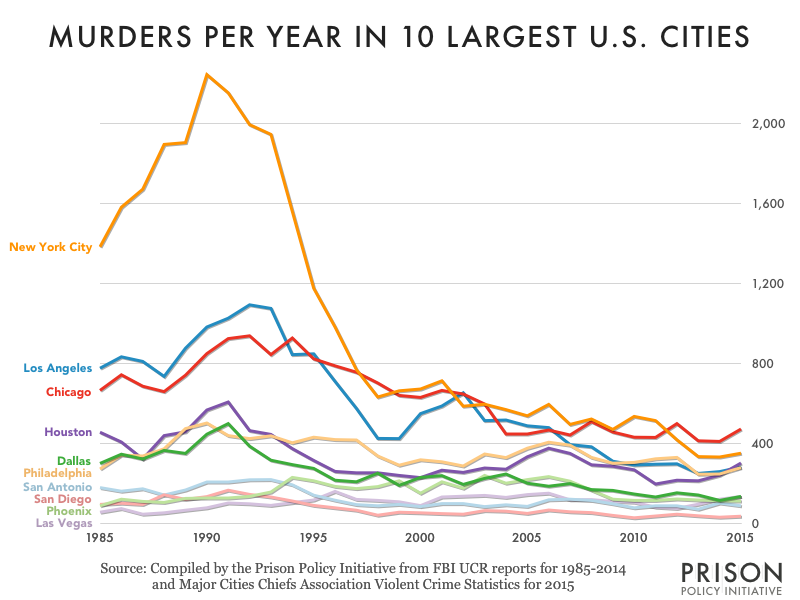

The following chart shows that after a rapid drop in the 1990s, the number of murders in the U.S.’s ten largest cities have remained at or near record lows:

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so I relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities.

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so I relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities.

While there is a notable rise in murder in Chicago (15% higher in 2015, and on track to exceed that in 2016), any discussion of the number of murders in Chicago needs to start with the fact that there have been half as many murders each year in the last decade than during the early 1990s.

It’s certainly true that a lot of major cities had increases in murder in 2015; but these were mostly small increases. In the historical view, murder remains at a record low.

Data sources: I compiled the totals for murder and non-negligent manslaughter from all agencies serving populations over 1,000,000 for 1985-2014 from the FBI UCR data. Data for 1985-2012 were available using the Data Tool, and totals for the same agencies for 2013 and 2014 were compiled from Crime in the United States 2013 and Crime in the United States 2014. Because the UCR full year report for 2015 has not yet been released, I used the totals published by the Major Cities Chiefs Association for 2015.

Prison Policy Initiative is excited to welcome two new staff members!

by Alison Walsh,

September 2, 2016

Please welcome our new Policy Fellow, Joshua Aiken, and our new Policy Analyst, Wendy Sawyer!

Joshua recently graduated with a Master’s in Refugee and Forced Migration Studies and a Master’s in U.S. History from the University of Oxford, and he holds a Bachelor’s in American Culture Studies and Political Science from Washington University in St. Louis. Joshua also studied solitary confinement and mandatory minimum policies as an advocacy intern for Human Rights Watch, and he worked as an oral history intern for the Missouri History Museum.

Wendy earned a Master’s in Criminal Justice from Northeastern University and a Bachelor’s in Afro-American Studies from the University of Massachusetts. She has worked as an investigator for the Civilian Complaint Review Board in New York and as a research associate for the Institute on Race and Justice in Massachusetts.

Joshua and Wendy will be taking the lead on exciting new reports and explainers for our National Incarceration Briefing Series, so stay tuned for updates!

Welcome, Joshua and Wendy!

The Atlanta-based foundation recognized the Prison Policy Initiative for our report Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving. This report exposed a little-known, but extremely harmful, law that automatically suspended driver’s licenses for drug offenses, regardless of whether the offenses involved driving or road safety. The state would then charge $500 for reinstatement, further ensuring that people with drug convictions would have a hard time getting employment or fulfilling familial needs.

The Atlanta-based foundation recognized the Prison Policy Initiative for our report Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving. This report exposed a little-known, but extremely harmful, law that automatically suspended driver’s licenses for drug offenses, regardless of whether the offenses involved driving or road safety. The state would then charge $500 for reinstatement, further ensuring that people with drug convictions would have a hard time getting employment or fulfilling familial needs.  Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so I relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities.

For most cities, murder is much lower now than during the 1980s or 1990s. The data for 1985-2014 comes from the FBI. The FBI has not published the 2015 full year data yet, so I relied on data from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which historically is very similar if slightly higher than the FBI’s figures. For that reason, this graph may overstate the increase in murder in 2015 in these cities.