Please support our work this Giving Tuesday.

by Peter Wagner,

November 29, 2016

Justice reform needs your support like never before. The good news is that after decades of prison growth, the public is starting to embrace criminal justice reform. The bad news is that we just elected a "law and order" President who says that crime is at record heights. (The truth is that crime is just off from a historic low.)

Our work just got harder, especially at the federal level. But there are many opportunities for change at the state level where most of the prisons are.

The Prison Policy Initiative excels at finding the missing data that is holding back criminal justice reform in the states. This year we:

-

Produced a report, States of Incarceration: The Global Context, that showed that every state — even the “progressive” states — use incarceration far more than the other nations of the world.

-

Broadened the movement’s scope by putting the numbers on the size of each state’s probation population. Our report, Correctional Control, showed that probation, intended as an alternative to incarceration, now reaches almost twice as many people as the prison and jail systems.

-

Unlocked rare government data to show that the ability to pay money bail is impossible for too many defendants because it represents eight months of a typical defendant’s income. Detaining the Poor also showed how much harder it is for women and people of color to afford bail.

These reports have reshaped the debate around criminal justice reform in this country. A small group of individual donors made these reports — and our legislative victories — possible. To continue this fight, we need your help. Can you make a gift to support our work today?

As a bonus, a group of donors will match the first $30,000 that we receive from this appeal. So any gift you can make will automatically go twice as far.

Thank you for taking a stand for justice, fairness, and truth at this time when all three are under attack.

Donate

A recent analysis finds that the most frequently incarcerated in New York City jails struggle with mental illness and are locked up for low-level offenses

by Bernadette Rabuy,

November 16, 2016

A recent analysis uncovers a counterintuitive finding: the people most frequently incarcerated in New York City jails are also people who would be better served with social services in the community.

A 2015 report by the city’s department of health used health data to examine the 800 people who were most frequently incarcerated in New York City jails from November 2008 through December 2014. The authors found that, in comparison to the rest of the people incarcerated in New York City jails, the frequently incarcerated were:

- Older

- More likely to be Non-Hispanic black

- More likely to be diagnosed as seriously mentally ill

- More likely to have a history of significant drug and alcohol use

- More likely to mention homelessness in their full history and physical examination

At the same time, the frequently incarcerated individuals were:

- More likely than the other people admitted to New York City jails to have low-level offenses. Two-thirds of the frequently incarcerated group was locked up for low-level theft, possession of small quantities of drugs, trespassing, or fare evasion.

During the six-year period, the group had a median of 21 incarcerations with a median length of stay of 11 days in jail. As a result, it cost the city $129 million to lock up and provide health care to just these 800 people.

The report’s findings on the needs of the most frequently incarcerated makes the growing popularity of “mental health jails” troublesome. Instead of recognizing that jail may not be the best solution to mental illness or substance abuse, municipalities are adopting reforms that call jails by other, gentler names without addressing the systemic issues that make jails a particularly tough place for those struggling with mental health and substance abuse.

In California, for example, the public has shown overwhelming support for alternatives to incarceration, yet even still, county legislators and sheriffs have been staunch supporters of new jail construction. At the same time, there is evidence that these county officials recognize the growing movement for reform that’s taking place in California and beyond and, in response, have moved away from the tough-on-crime narrative. Activist and author James Kilgore calls these attempts to repackage jails as social service providers, “carceral humanism.” It explains why Los Angeles County’s proposal for a new women’s jail has sometimes been called a “women’s village” and why San Mateo County is so proud of its “compassionate jail.”

But even brief jail stays can be incredibly disruptive. They separate families, some of whom struggle to keep in touch. And they can lead to a loss of employment for people who already struggle to find gainful employment.

This report shows that America’s use of jails to address mental health and substance abuse is not working. And there are already too many examples of jails failing to provide adequate mental health and substance abuse services. It’s time for our social policies to be more creative and look beyond institutionalized settings like jails.

Our just completed year was our most successful yet. Recap our victories and help us plan for more wins this year.

by Peter Wagner,

November 8, 2016

We just released our 2015-2016 Prison Policy Initiative Annual Report, and I’m thrilled to share some highlights of our work with you. We had another great year of leading innovative campaigns while also strengthening the movement with long-absent data and resources.

Part of what makes the Prison Policy Initiative unique is the way in which we analyze and present obscure or underutilized data to fill information gaps that are stalling the movement against mass incarceration. For example, detaining people because they are poor is an offensive idea, but it was difficult to prove that this is exactly what the American cash bail system does. This year, Bernadette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf were able to support this claim with evidence in our report Detaining the Poor: How money bail perpetuates an endless cycle of poverty and jail time by putting an obscure government dataset to good use. In addition, Aleks Kajstura and Russ Immarigeon wrote a report putting each state’s incarceration of women into global context and showing that even the most progressive U.S. states are out of step with the rest of the world.

We did all of this while continuing to achieve real change on our focused campaigns:

To assist us in our mission to continue fueling the movement against mass incarceration, we have grown and added two new full-time members to our team. As the organization grows, so do our financial needs. Generous contributions from funders and individual donors will allow us to complete exciting new reports (along with some much-needed updates to old ones) in the new year. We would love you to join these donors by making a one-time or monthly contribution to our work (link no longer available). And please know that any gifts we receive through the end of 2016 will be matched by other donors, so your generosity will be able to go twice as far.

Thank you for taking the time to celebrate this year’s success with us.

Americans’ respect for local police is apparently much higher than their confidence in the police in general.

by Wendy Sawyer,

October 26, 2016

Good news from Gallup this week that “surging” numbers of Americans respect the police needs a gentle reminder that this is only a small part of the picture.

Gallup asks Americans two similar-sounding questions about attitudes towards police every year that get very different responses. In the fall, Gallup’s poll asks about respect specifically for local police; in the summer, another question asks about confidence in the police as an institution in American society.

The positive responses reported this week were for the question “How much respect do you have for the police in your area?” Americans’ respect for local police is apparently much higher than their confidence in the police in general.

Last year, the Prison Policy Initiative’s Rachel Gandy charted confidence in the police, which showed that in 2015, just 52% of Americans had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the police as an institution in American society. This June, Gallup reported that confidence went up only 4% from last year’s 22-year low, and just “a slim majority of Americans have confidence in the police as an institution.”

Jesse Walker on Reason.com offers a quick analysis of cultural conditions in 2016 that may account for the increase in respect for police, and points out the important differences between the measures of respect and confidence.

Most obviously, when Gallup asks about respect for police, it asks about local police, who may be familiar faces to many Americans – even neighbors and relatives on the force. This question also comes at a time when the memories of the shootings of police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge are still fresh. Respect for police is a given. It dominates presidential debates and is a common refrain used to denounce critics of police brutality.

Of course Americans respect the police. But do they trust them? That is the question of confidence.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s new regulations increase protections for people released from prison and jail, who are often forced to use release cards.

by Aleks Kajstura,

October 5, 2016

Today, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued a final rule on prepaid debit cards. Last year, the Prison Policy Initiative and other groups urged the CFBP to use this rulemaking to address abusive practices related to prepaid debit cards issued to people upon their release from prison or jail. The CFPB’s decision today is a partial win, but more work remains to be done.

The good news is that release cards will be covered by the new consumer protections contained in the final rule. Specifically, correctional facilities will have to provide clear fee disclosures, card issuers will have to provide reliable access to account histories, and cardholders will have some ability to dispute inaccurate charges.

Prison Policy Initiative had argued that correctional facilities should be prohibited from requiring that people receive their money on prepaid cards. The CFBP declined to impose such a prohibition at this time. Instead, the Bureau acknowledged the concerns about release cards, but said more research would need to be done before it could consider taking action.

Finally, the CFPB ruling clarified that at least some release cards should be conforming to existing (and new) regulations:

[T]o the extent that… prison release cards are used to disburse consumers’ salaries or government benefits…, such accounts are already covered … and will continue to be so under this final rule.

As the CFPB proceeds with the “additional public participation and information gathering about the specific product types at issue”, correctional facilities are increasingly using these expensive cards to repay people they release — money in someone’s possession when initially arrested, money earned working in the facility, or money sent by friends and relatives.

Before the rise of jail release cards, people were given cash or a check. Now, they are instead given a mandatory prepaid Mastercard, which comes with high fees that eat into their balance. These cards charge for basic things like:

- Having an account (up to $3.50/week)

- Making a purchase (up to $0.95)

- Checking your balance (up to $3.95)

- Closing the account (up to $30.00)

To put this into perspective, if someone is released with $125, a $2-per-week maintenance fee is equivalent to a finance charge of 77% per year. If that same hypothetical cardholder makes ten purchases of $12 each, then a $0.50 per-transaction-fee would amount to $5, or 4% of the entire card balance (on top of maintenance fees). If the cardholder wishes to convert a prepaid card into cash, he or she must pay $10 to $30 (8% to 24% of the entire deposit amount) merely to close the account.

But while the new CFPB regulations take a more robust stance on fee disclosure, allowing many people to avoid predatory pricing, they won’t help incarcerated people, who have the cards foisted on them with no choice.

On Saturday, I was honored to accept, on behalf of the Prison Policy Initiative, the Foundation for Improvement of Justice's Paul H. Chapman Award for our report and campaign to end Massachusetts' suspension of drivers licenses for unrelated drug offenses.

by Peter Wagner,

September 30, 2016

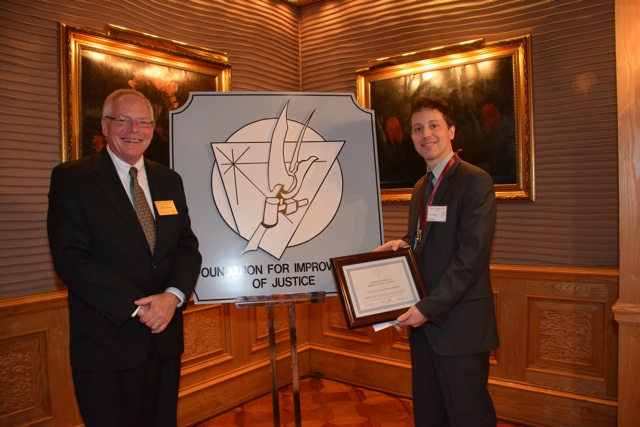

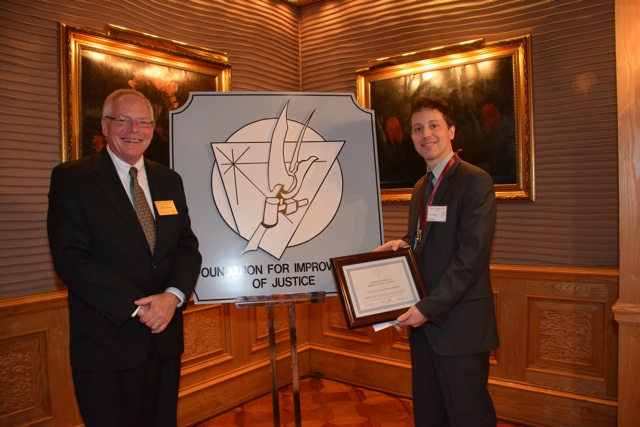

On Saturday, I was honored to accept, on behalf of the Prison Policy Initiative, the Foundation for Improvement of Justice’s Paul H. Chapman Award.

The Atlanta-based foundation recognized the Prison Policy Initiative for our report Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving. This report exposed a little-known, but extremely harmful, law that automatically suspended driver’s licenses for drug offenses, regardless of whether the offenses involved driving or road safety. The state would then charge $500 for reinstatement, further ensuring that people with drug convictions would have a hard time getting employment or fulfilling familial needs.

The Atlanta-based foundation recognized the Prison Policy Initiative for our report Suspending Common Sense in Massachusetts: Driver’s license suspensions for drug offenses unrelated to driving. This report exposed a little-known, but extremely harmful, law that automatically suspended driver’s licenses for drug offenses, regardless of whether the offenses involved driving or road safety. The state would then charge $500 for reinstatement, further ensuring that people with drug convictions would have a hard time getting employment or fulfilling familial needs.

Our report provided persuasive evidence of the law’s failure as a crime deterrent, pointed out that the law actually made the roads less safe because it increased the number of unlicensed and uninsured drivers, and included a detailed analysis of the resources wasted on enforcing unnecessary license suspensions.

Our followup advocacy helped the state understand that the law was punishing entire communities, not just a few individuals; and the law was repealed earlier this year.

Thirteen other states and the District of Columbia have similar laws, so we will be using the prize money to expand our campaign for reform of this outdated relic of the War on Drugs.

Below are some pictures of the award ceremony.

Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

by Joshua Aiken,

September 30, 2016

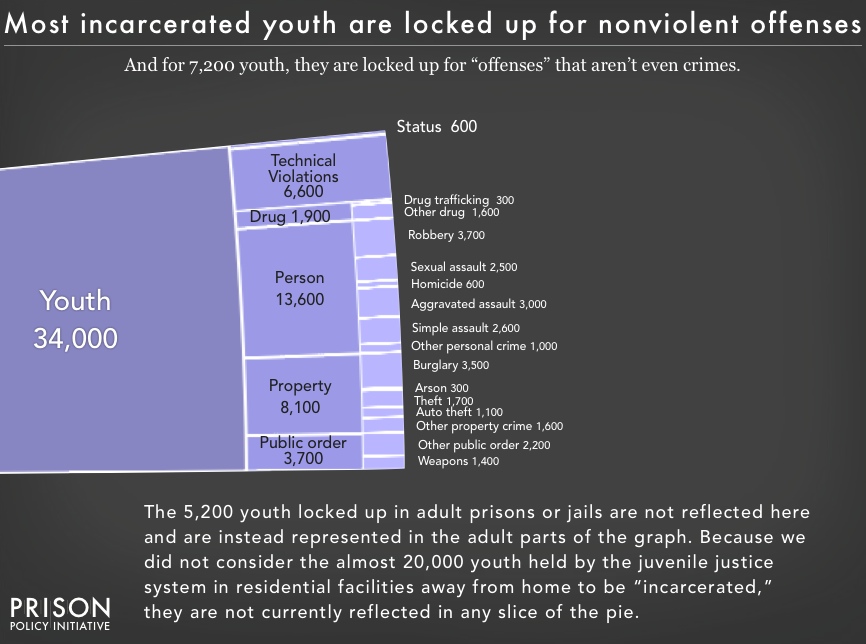

While comprehensive criminal justice reform for adults has failed to pass in Congress, a bill lingering in the Senate could still overhaul how our juvenile justice system works. The bipartisan legislation, which passed the House by an overwhelming 382-29 vote, would create several new policies that juvenile justice advocates have been requesting for years.

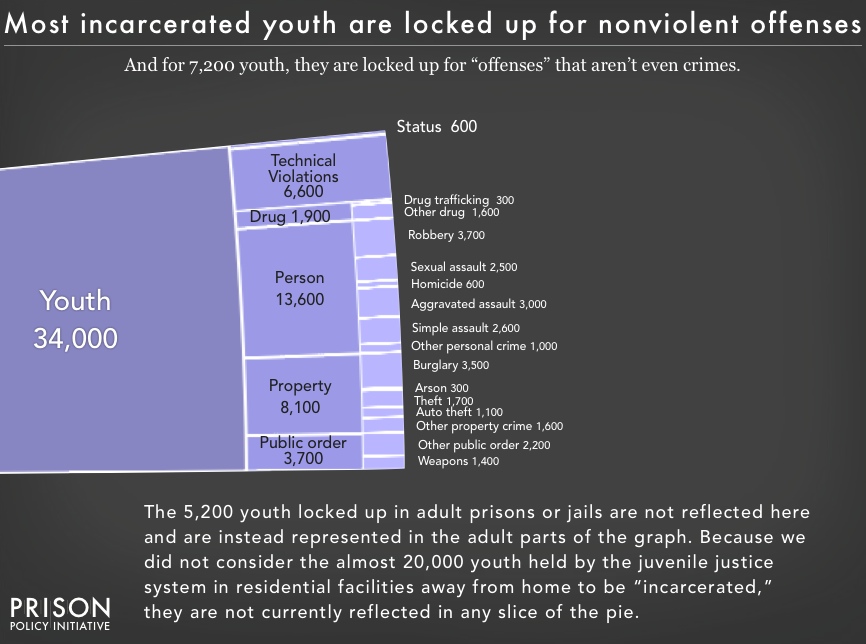

The proposed reauthorization of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act would withhold funding from states that put youth in adult prisons, require states to collect data on racial disparities in the juvenile justice system, ban the practice of shackling pregnant girls, and prohibit states from locking up youth for “status offenses.”

These reforms are desperately needed. In our 2016 report, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie we highlighted one of the most disturbing facets of our juvenile justice system: that we lock young people up for behaviors that are not law violations for adults—like running away or skipping school.

Talking about “status offenses” is important because status offenses aren’t even crimes. These offenses relate to a person’s age: skipping school, breaking curfew, or even talking back can land a young person behind bars. Increasingly, those young people are girls.

In an incredible piece for Mother Jones last week, Hannah Levintova details how bias and over-criminalization are ensnaring more and more girls into the criminal justice system. Levintova explains:

Between 1995 and 2009, cases of breaking curfew rose by 23 percent for girls—and just 1 percent for boys. In 2011, girls made up 53 percent of runaway cases brought before a judge. Between 1996 and 2005, arrests for “simple assault”—which could be as minor as a daughter throwing a toy at her mom—went up 24 percent for girls and down 4 percent for boys. By 2013, girls were almost twice as likely as boys to be in detention for simple assault and certain other nonviolent offenses.

Girls, argues Professor Andrew Spivak, are faced with types of “judicial paternalism” where “courts think that they need to protect girls and give them guidance.” Professor Stacy Mallicoat, in a 2007 study, showed that probation officers often attribute girls’ offending behaviors to their sexual behavior, drug use, and negative family relationships. Girls, and especially girls of color, get blamed. Meanwhile, when describing boys, probation officers were less likely to see their criminal behaviors as coming from these sources. As Levintova puts it, the justice system sees boy’s behaviors as “lifestyle choices” while the morals of girls are punished.

The disparate prosecution of status offenses sheds light on the deeply gendered ways our criminal justice works. And these offenses end up having a disastrous and long-lasting impact on girls:

Even a brief period in detention can lead to mental and

physical health issues, higher unemployment rates, lower lifetime

earnings, and substance abuse. The moral judgment that underlies the charges girls face can also change how they see themselves. “Once they internalize that they are ‘bad girls,'” says [Jeannette] Pai-Espinosa, “it almost creates a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The bill’s sponsors in the House are hopeful that the legislation can reach President Obama’s desk, but some legislators are strongly opposed.

The Massachusetts prisons system wants to make it harder to visit and harder to mail materials to incarcerated people. We tell them that's a bad idea.

by Joshua Aiken,

September 28, 2016

Incarcerated people and their families are more likely to succeed if they are allowed and encouraged to remain in touch.

Unfortunately, the Massachusetts Department of Corrections is proposing new regulations that will make it harder for families to stay in touch. The proposed amendments would restrict the number of people allowed on a pre-approved visitation list, subject private attorneys’ correspondence with their incarcerated clients to unconstitutional review, and limit incarcerated peoples’ ability to receive more than five pages a day of photocopied material.

Tomorrow, at a public hearing, the Department will be taking comments on these and other proposed amendments to the Code of Massachusetts Regulations. Today, I submitted two letters on behalf of the Prison Policy Initiative addressing these counterproductive proposals.

My letters make the case that:

- The Department of Corrections should encourage, not discourage, written communication from loved ones.

- Forcing incarcerated people to choose which members of their families and which of their friends can visit them isn’t just unnecessary. It’s wrong.

Bill Newman takes on injustice 90 seconds at a time. In the newest episode of his Civil Liberties Minute podcast, he takes on the practice of locking up poor people because they can't afford bail.

by Peter Wagner,

September 27, 2016

Friend of the Prison Policy Initiative Bill Newman has again featured our research in his Civil Liberties Minute podcast produced with the ACLU. This time he takes on the epidemic of jailing the innocent before trial in a powerful 90 second explainer.

You can listen or subscribe on iTunes and the transcript with some links to some of the source material is below.

Thank you, Bill!

In Jail And Innocent

Why is your mother, father, sister, brother, lover or friend, who is presumed innocent, still locked up in jail?

Know this: he or she is not alone. Of the 664,000 people locked up in local jails today, 70% of them have not been convicted or sentenced for any crime. Really – 70% are locked up only because they can’t make bail.

In the past 15 years 99% of the growth in the jail population comes from people who don’t have the 50 or 100 or 250 or 400 dollars to get bailed out. When the person held on bail finally goes to court he will be offered a deal. Plead guilty and you can get out, time served, go home today. Or you can say you’re innocent and want a trial, and stay locked up for days, weeks, months, or years. What would you do?

The Eighth Amendment to The Constitution in theory guarantees a reasonable bail and bail in theory is only supposed to be used to help insure the attendance of the defendant at trial – not as a subterfuge for pre-trial detention.

But as the numbers and the lives ruined prove, the constitutional principles of reasonable bail and innocent until proven guilty really only applies to those who are economically well off enough to make their bail.

The United States is the only country in the world that sentences people under 18 to die behind bars. Which states do it, and why?

by Joshua Aiken,

September 15, 2016

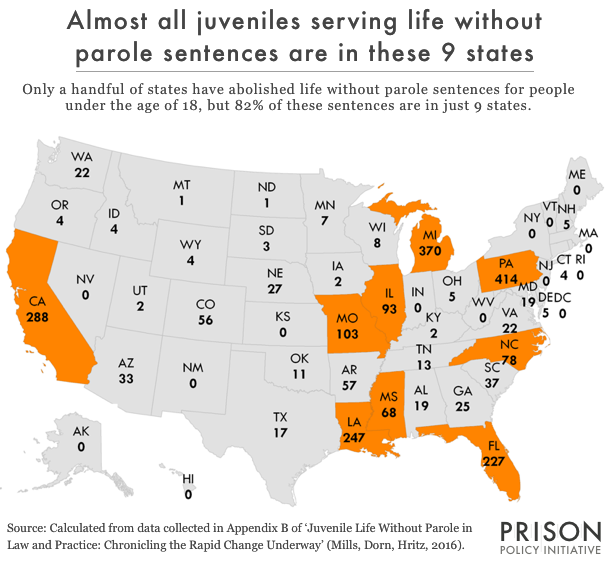

The United States is the only country in the world that sentences people under 18 to die behind bars. The Supreme Court has twice declared many of these sentences to be unconstitutional, but some states are resisting the Court’s required reforms. (In 2012, the Court struck down mandatory juvenile life without parole sentences. Earlier this year, the Court made that decision retroactive.)

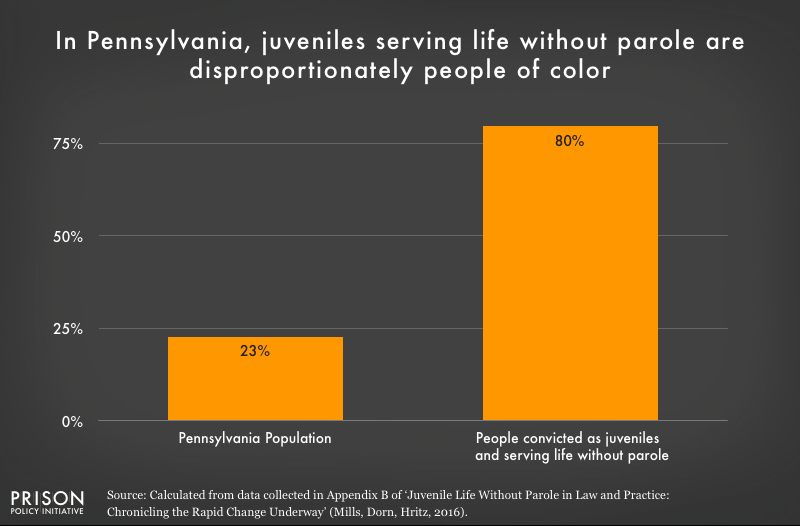

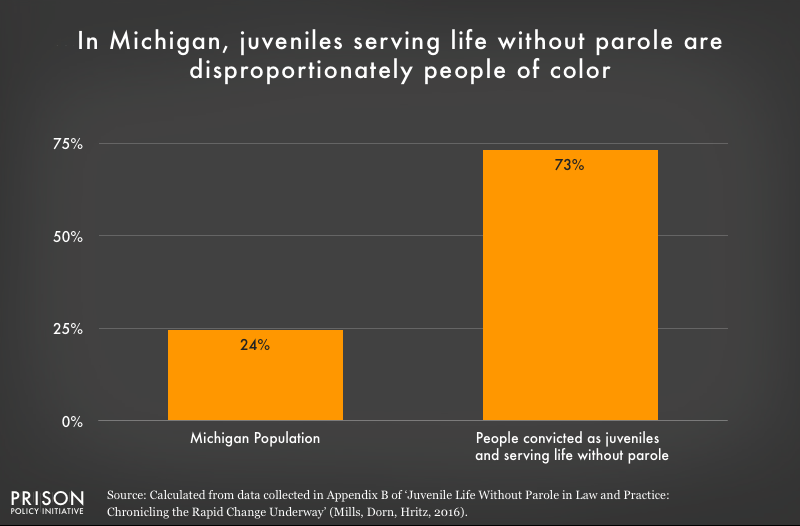

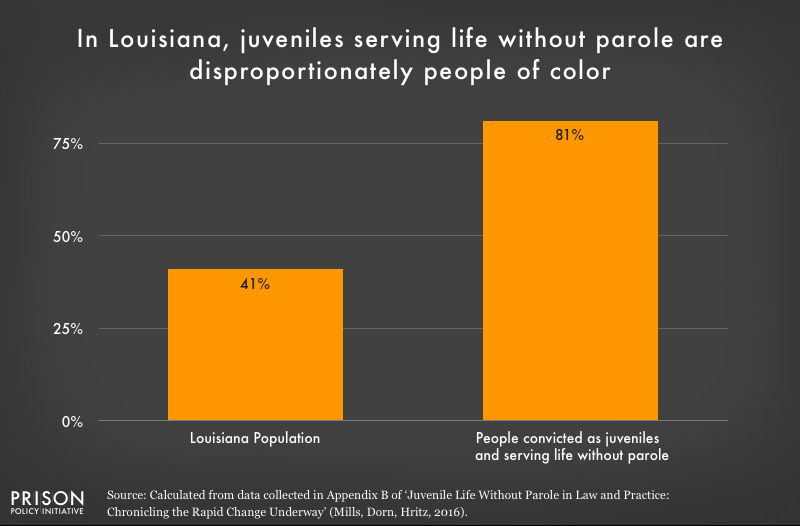

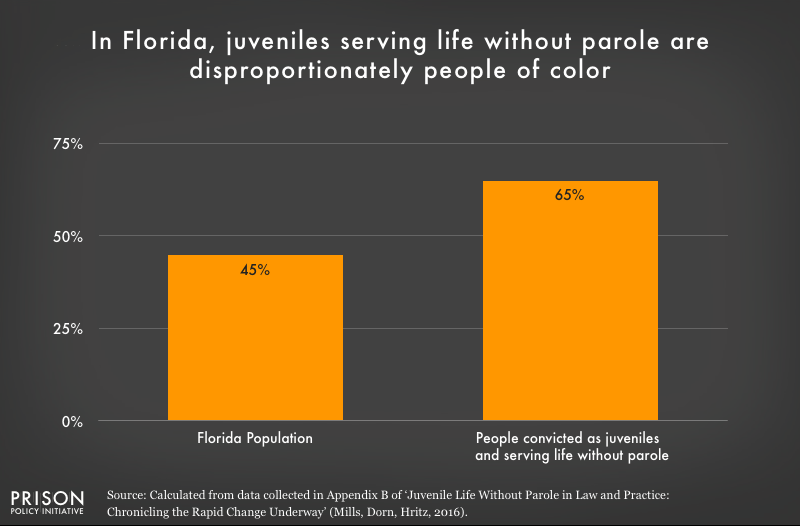

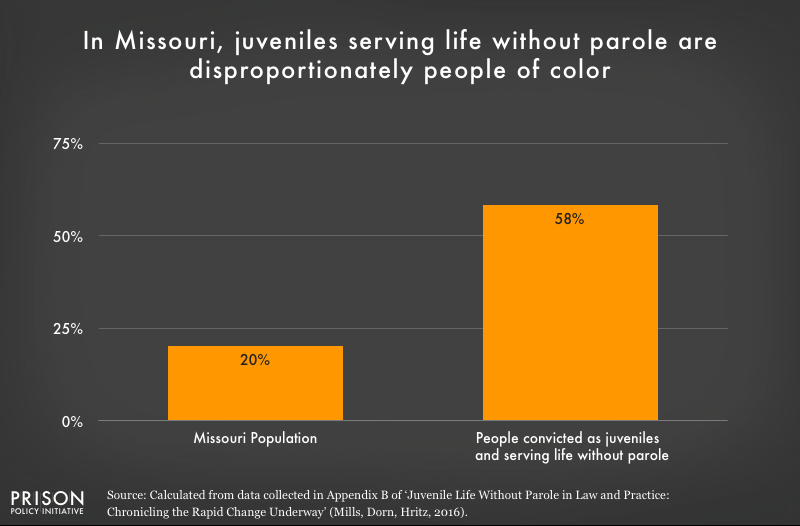

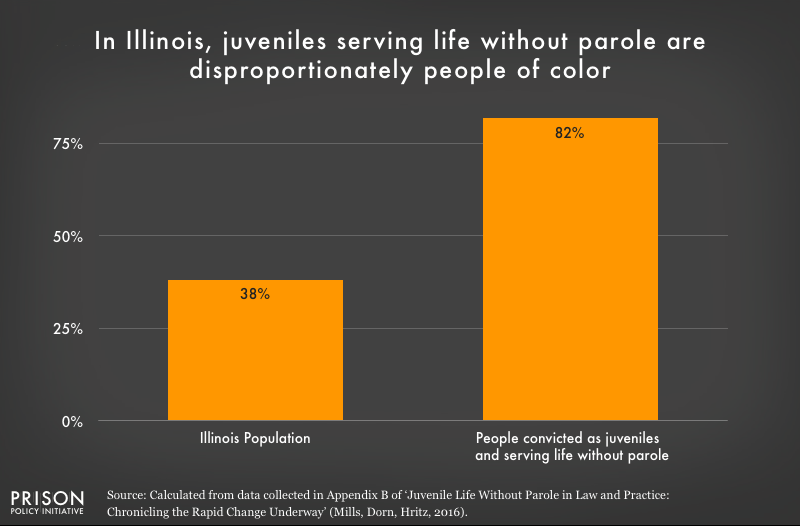

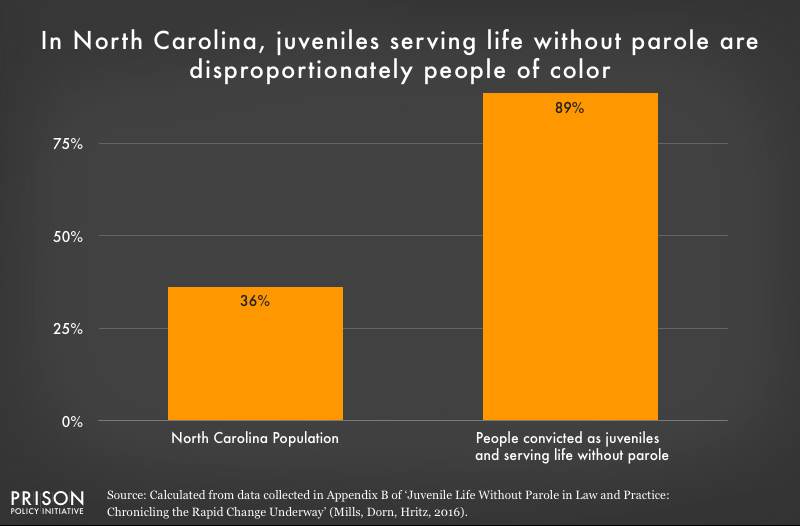

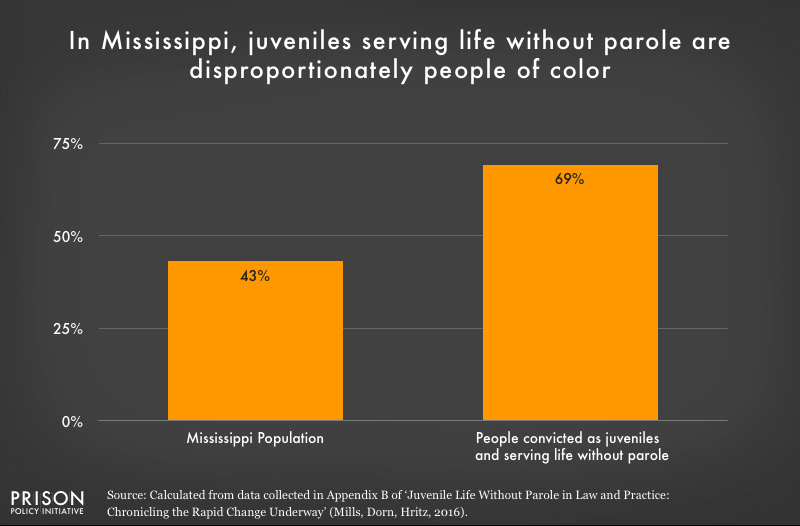

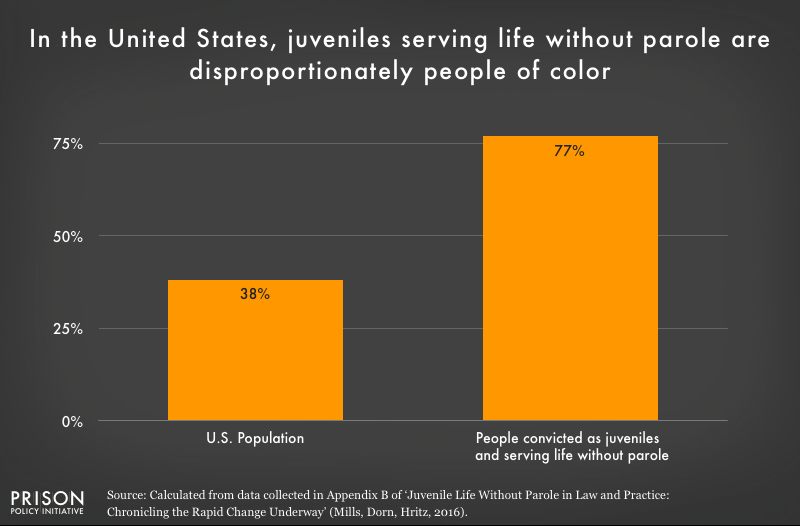

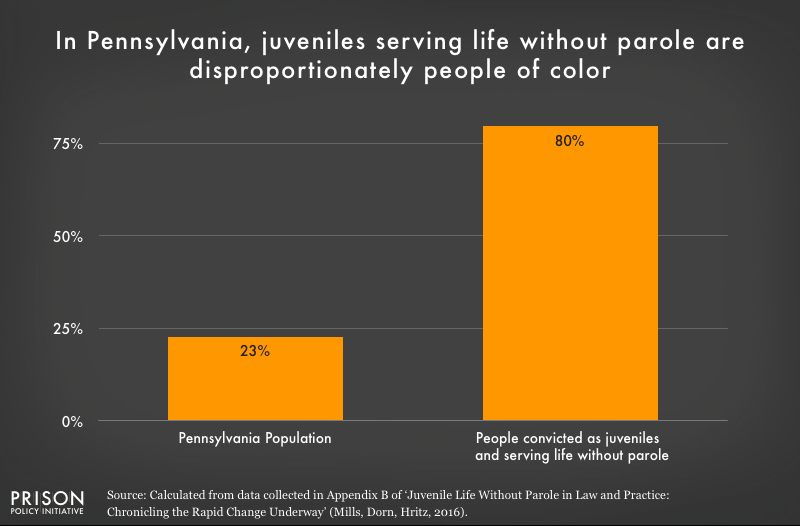

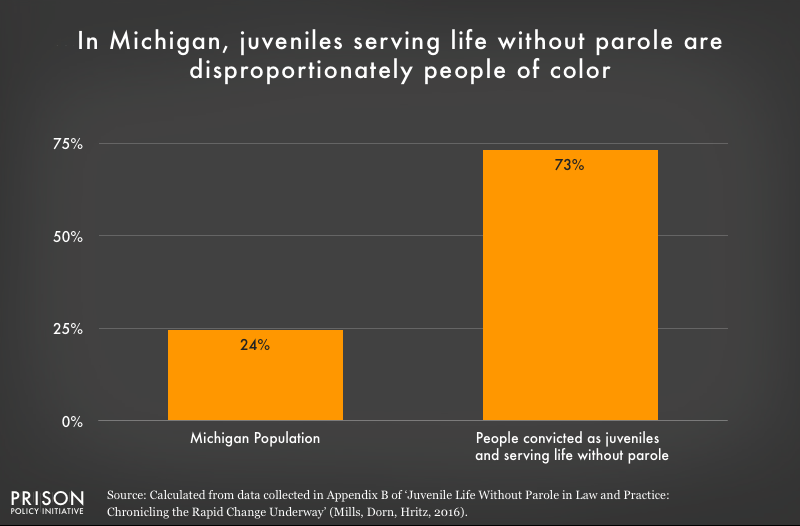

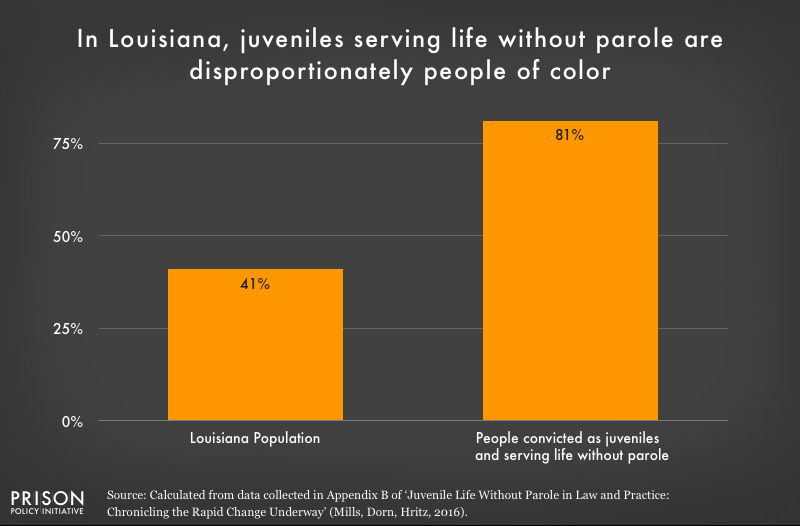

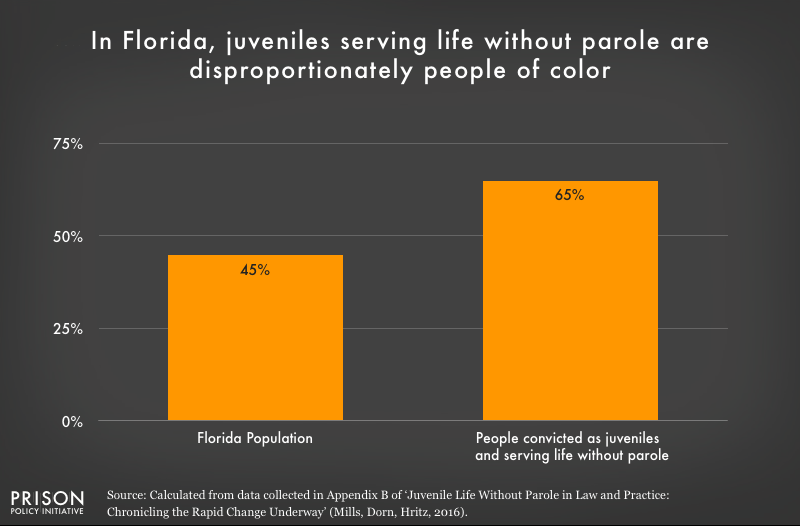

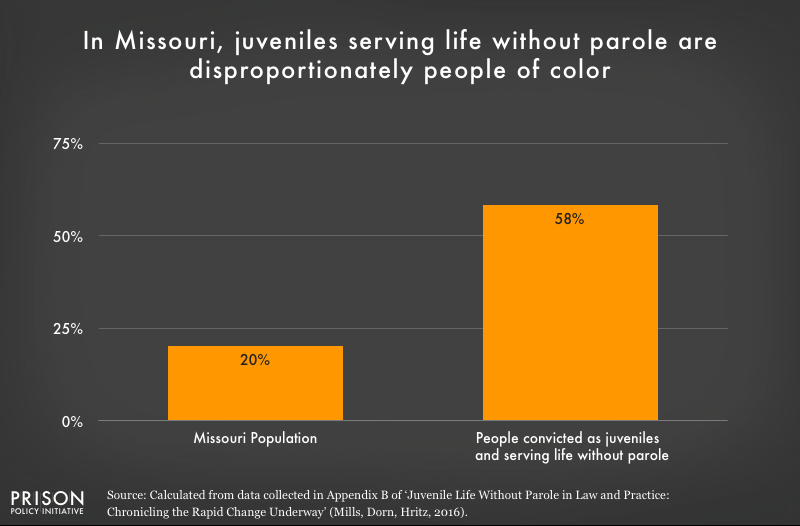

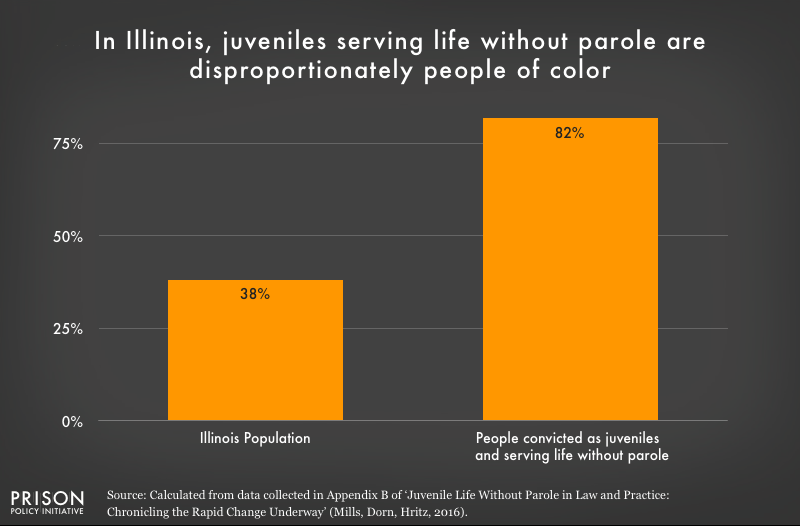

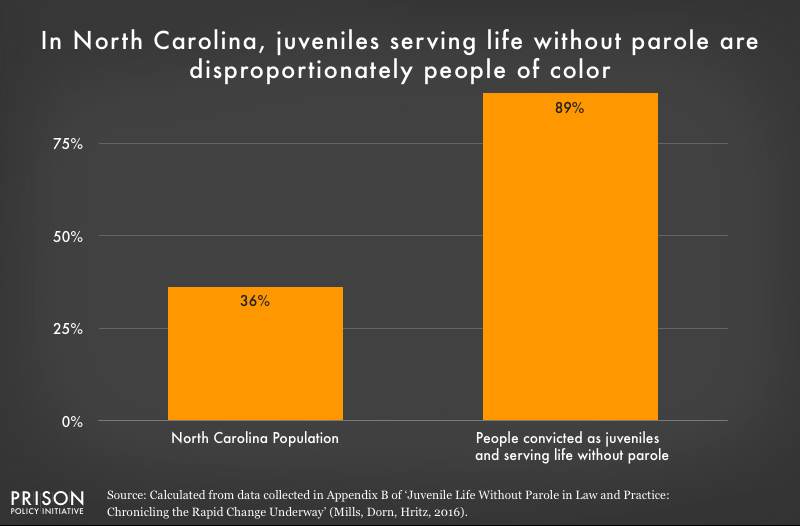

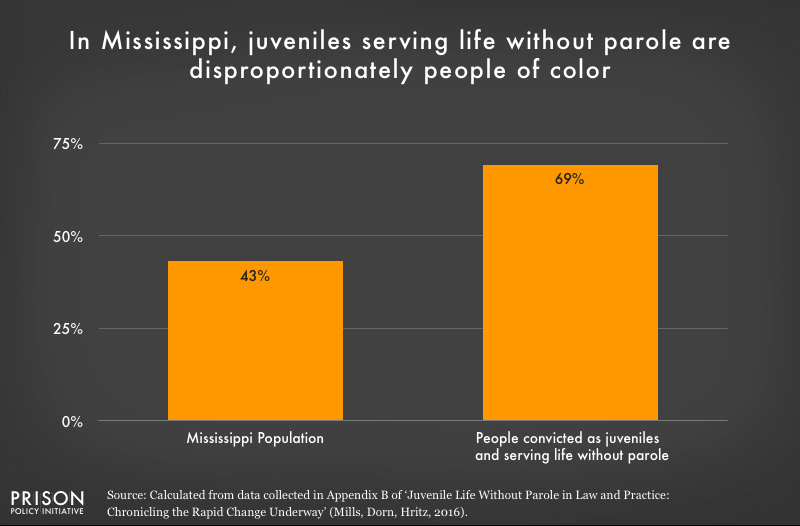

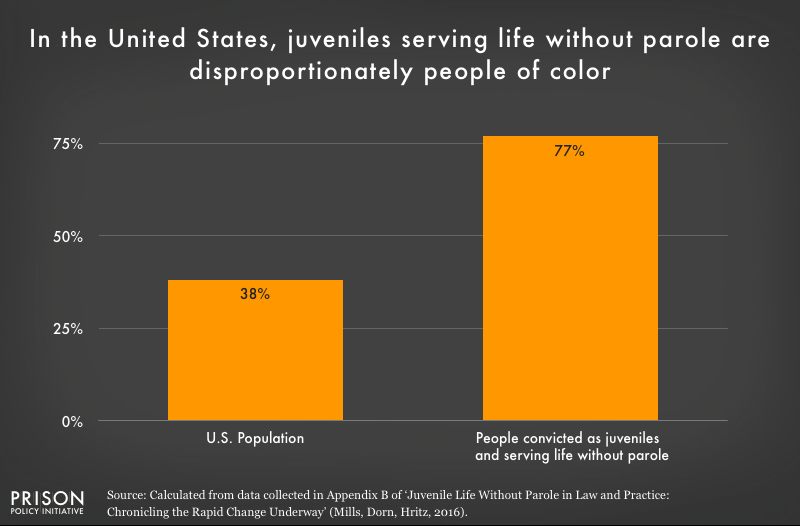

While a number of states continue to use life without parole sentences for juveniles, new research shows that those juveniles are largely and increasingly people of color. A recent study by researchers from the Phillips Black Project found that people of color are overrepresented in the juvenile life without parole population “in ways perhaps unseen in any other aspect of our criminal justice system.”

Young black people are hit hardest by prosecutors’ punitive approach. This is unsurprising. Black children are more likely to be punished by their teachers for the same behaviors, are 2.3x more likely to be referred to law enforcement by school officials, and 3x more likely to be suspended or expelled than their white peers.

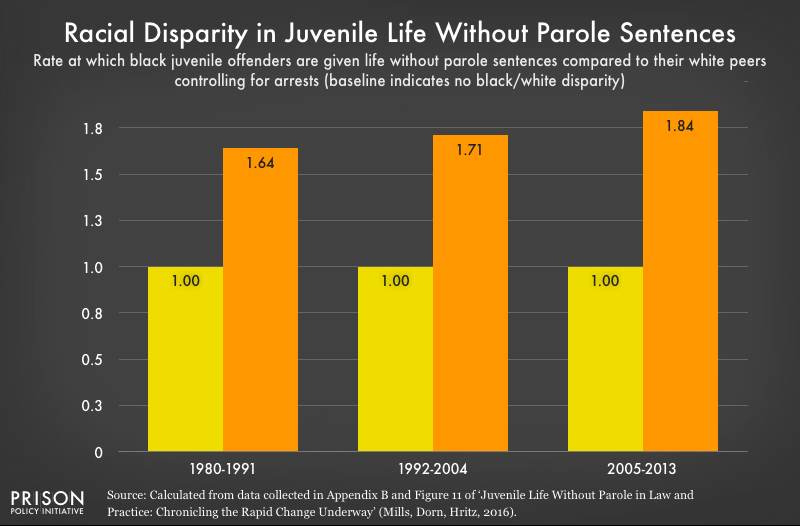

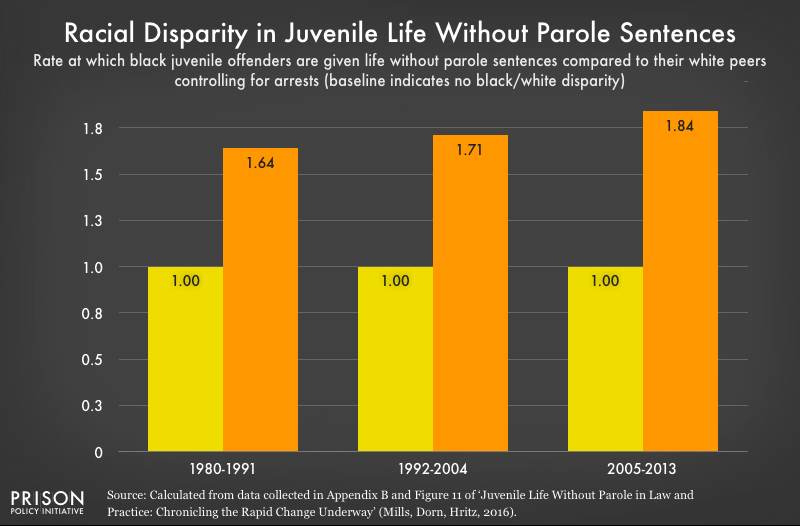

Being sentenced to die behind bars, however, is especially egregious. The Phillips Black Project found that black youth are twice as likely to receive a juvenile life without parole sentence compared to their white peers for committing the same crime.

Significantly, the researchers found that racial bias exists in the prosecutorial and judicial phases of the criminal justice system. Controlling for the fact that black youth have more encounters with the police, this study compared the number of black and white juveniles life without parole sentences against the number of relevant arrests.

By focusing only on the disparate outcomes that occur after the moment of arrest, the Philips Black Project researchers call attention to how prosecutors and courts fail to fairly determine guilt, innocence and punishment.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.

This finding gives new urgency to the 2014 findings of psychologists in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that black youth are generally less likely to be seen as innocent and more likely to be perceived as adults. This result was particularly strong when black youth were accused of a serious crime.

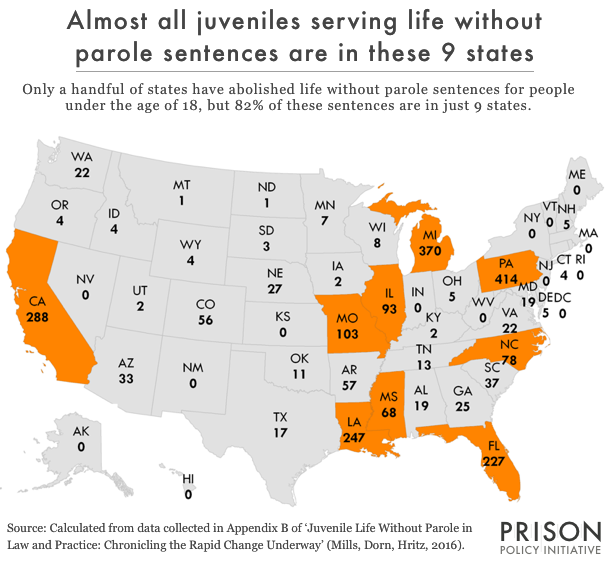

The good news is that juvenile life without parole sentences are falling out of favor; at least eighteen states have abolished the sentence altogether. Sadly, there are a handful of states that have steadfastly held onto the punishment. Just nine states account for four out of every five cases.

Legislators in these states have been remarkably resistant to reform. Take Louisiana for instance. This June, after passing the House with a resounding 83-2 vote, a Senator filibustered the bill with just ten minutes left in the legislative session. For the thousands serving these sentences, the next legislative session, and a chance at a second chance, can’t come soon enough.

Juvenile life without parole sentences are not only irredeemably harsh but are also indicative of the racial biases ingrained in our criminal justice system. Below I’ve put together graphs showing just how overrepresented people of color are in eight of the nine states responsible for the vast majority of juvenile life without parole cases. (California does not provide data on the race and gender of its juvenile life without parole population.)

Note: In order to calculate the national and state-level people of color population, I used 2015 U.S. Census data as to match the data collection period of the Mills, Dorn, Hritz study. Additionally, my use of people of color is based on analyzing Census data for all respondents who do not identify as ‘Non-Hispanic White.’

Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Paul Jones (left) board member of the Foundation for Improvement of Justice with Peter Wagner, Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative. Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

Winners of the 2016 Paul H. Chapman Award. From left to right: Carol Tracy, Brenda Lawrence, Peter Wagner, Dirk C. Moore, Arleen Joell and Julia R. Wilson.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.

The Philips Black Project data controls for differences in policing practices to identify increasingly racially disparate outcomes that originate with prosecutors and the courts.