Video conferencing enthusiasts agree: video calls are not the same as in-person visits

by Bernadette Rabuy,

September 26, 2017

The public, the media, and policymakers agree: replacing in-person jail visits with video calls is foolish and needlessly cruel. In an article last week, VC Daily, which describes itself as a niche community of video conferencing enthusiasts, agreed: “Video conferencing technology has come a long way in the past decade, but even in its most experimental current forms it cannot replicate time spent with family and friends in the flesh…”

VC Daily was quick to acknowledge that it may seem like an unlikely supporter of in-person visits, and it explained why video calls are a poor replacement of in-person visits:

As much as we consider ourselves here at VC Daily to be cheerleaders for the technology and use of video conferencing, the bottom line is that video conferencing just isn’t the same as in-person communication. At least, not right now. It is a great substitute when distance and circumstance make sharing the same space impossible, impractical, or just plain expensive.

VC Daily understands that in-person jail visits are far from impossible, impractical, or expensive:

- In-person jail visits are not impossible. Although this is quickly changing, most jails still provide in-person visits.

- In-person jail visits are not impractical. In-person visits, not video calls, are the norm in state and federal prisons. Jails can and should provide in-person visits too, especially since families are generally able to visit incarcerated loved ones more easily when they are close by in a local jail than many miles away in a prison.

- In-person jail visits are not expensive. Traditionally, jails did not charge families to visit their incarcerated loved ones. Charging families to see their incarcerated loved ones is one of the negative consequences of the growth of the video call industry and a practice discouraged by the American Correctional Association. Jails do expend resources to provide in-person visitation, but in-person visitation can lead to a reduction in recidivism so it’s a worthy investment.

VC Daily went on to admit that, even as a community of video conferencing enthusiasts, it believes that denying incarcerated people human contact infringes on basic human needs:

However, as an L.A. Times editorial noted just a few months ago, once you start employing video conferencing to replace human physical interaction, you run the risk of dangerously undermining a person’s basic human needs… We usually end these posts dreaming of a hypothetical future in which video conferencing is the good guy, the tech that can make great things possible. But this certainly takes the fun out of our hypothetical.

VC Daily’s critique gets at the heart of what is so perverse about the way that jails use video calls: it’s a rare example of a technology being used to separate, rather than connect, people. This harmful practice is in part why VC Daily concludes, “[v]ideo conferencing is an addition to our lives, not the venue for them.”

One of the earliest and most famous investigations of conditions of confinement began 130 years ago today.

by Emily Widra,

September 26, 2017

The high walls that keep incarcerated people in prisons and jails also keep the public – and public oversight — out. One of the key drivers of criminal justice reform is investigative journalism that uncovers injustices and forces our elected officials to pay attention to otherwise hidden institutions.

One of the earliest and most famous investigations of conditions of confinement began 130 years ago today when journalist Nellie Bly was committed to New York City’s insane asylum, Blackwell’s Island. Bly’s goal was to reveal what life was like behind asylum bars in New York City. Despite the rumors of abuses at the asylum, Bly was reluctant to believe that “such an institution could be mismanaged, and that cruelties could exist ‘neath its roof” until she experienced them firsthand. She checked into a rooming house, concocted a story about having lost her luggage and money, was turned over to the police, and quickly declared insane by a judge. The whole process, from story conception to forcible commitment, took only four days.

During her ten days behind bars on Blackwell’s Island in 1887, Bly witnessed numerous instances of physical and emotional abuse, as well as the inability of staff to provide proper care for the patients. To expose these truths, Bly wrote three articles – Behind Asylum Bars, Inside the Madhouse, and Untruths in Every Line – revealing the institutional mismanagement, abuses, and harsh conditions the patients experienced at Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum.

Bly’s investigative journalism had immediate and long-term impacts on the care provided for people with mental illnesses. The asylum made rapid practice and administrative changes following the publication and a Grand Jury was convened to investigate the reported abuses, leading to real transformation in the oversight, practices, and funding of the asylum.

In our view, investigative journalism is a key part of a functioning democracy and is key to criminal justice reform. Much of our research is designed to empower journalists to tell the story of our criminal justice system in new ways, and we make it a point to highlight the most important investigative stories of the year. (See our list for 2015 and 2016.)

What’s interesting about Bly’s book is not just the subject matter, it is also the foundation for a discussion about how far we’ve come and how far we still have to go.

For more on Nellie Bly, see:

For more on mental illness in the criminal justice system, see:

HIV disproportionately impacts communities that are already marginalized by poverty, inadequate resources, discrimination — and mass incarceration.

by Emily Widra,

September 8, 2017

In a New York Times Magazine article published in June 2017, journalist Linda Villarosa highlighted the “hidden HIV epidemic” among Black gay and bisexual men in the Deep South. The overall decline of HIV rates in the US may give some people a premature sense of victory; this progress obscures the fact that HIV remains a significant problem for a disproportionate number of Black gay and bisexual men in this country, as Villarosa points out:

“Swaziland, a tiny African nation, has the world’s highest rate of H.I.V., at 28.8 percent of the population. If gay and bisexual African-American men made up a country, its rate would surpass that of this impoverished African nation — and all other nations.”

Villarosa mentions the systemic issues impacting HIV rates among southern Black communities, including the “crippled medical infrastructure,” the limited domestic funding and resources dedicated to HIV/AIDS, and the movement of the HIV epidemic from cities like New York and San Francisco to smaller cities with larger Black populations in the Deep South. Along these lines, Dr. Mark Dybul — an infectious diseases researcher and professor — describes HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis as “discriminatory” diseases because they disproportionately impact communities that are already marginalized by poverty, inadequate resources, and discrimination. Villarosa also briefly touches on the history of incarceration of a few of the men she interviewed, but the intersection of HIV, race, and incarceration deserves further investigation, especially considering the high rates of incarceration in the South.

There is little information available about LGBT people of color behind bars, and even less data on the rates of HIV and incarceration among men who have sex with men. In the public health literature that does exist on HIV, the category of men who have sex with men, or MSM, is applied broadly and inconsistently to self-identified gay and bisexual men, men with a lifetime history of male-to-male sexual contact, and/or men who self-report male-to-male sexual contact in the past 6 months, depending on the particular study. The lack of consistency and clarity when we talk about this population only makes it harder to address these issues. As Villarosa puts it, “too many black gay and bisexual men [are] falling through a series of safety nets.”

The existing studies begin to fill in the gaps in literature, but there is more work to be done to understand how the interactions of high rates of HIV and our criminal justice system disproportionately impact Black gay and bisexual men and Black MSM. Recent research suggests an overlap between HIV and incarceration:

- People at risk for incarceration are more likely than others to be at high risk for HIV infection. These risk factors include a history of drug use, low socioeconomic status, high prevalence of STIs, mental illnesses, and history of assault and/or abuse.

- An estimated 25% of Americans living with an HIV infection were incarcerated during 2008.

This is much worse for Black men, like the men that Villarosa interviewed. The compounding effects of HIV, incarceration, and discrimination intersect in the lives of Black gay and bisexual men and Black MSM.

- First, it is clear that the HIV epidemic among Black MSM that Villarosa points out is real. The CDC reported that “if current HIV diagnoses rates persist about 1 in 2 Black men who have sex with men (MSM) will be diagnosed with HIV during their lifetime.”

- And there are a lot of Black MSM in prison. Using data from the National Inmate Survey, 2011-2012, researchers found that 34.3% of Black men in prison were MSM, while only 8.9% of the total US population of MSM is Black. (The total Black MSM population is unknown, but would be useful for measuring overrepresentation.)

- These men who are at a heightened risk of HIV are especially vulnerable behind bars, where condoms are typically unavailable. (Male-to-male sexual contact contributes to over 70% of HIV diagnoses among Black men.)

- Finally, it looks like Black MSM are at high risk for both HIV diagnosis and incarceration. There is limited data on how much of the US Black MSM population has a history of incarceration, but one study found that 58.7% of a sample of 1,385 Black MSM self-reported a history of incarceration.

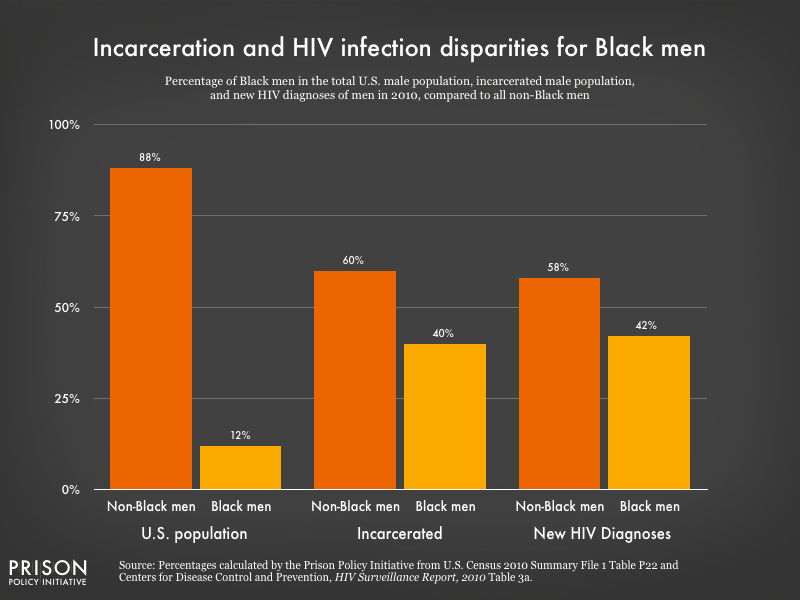

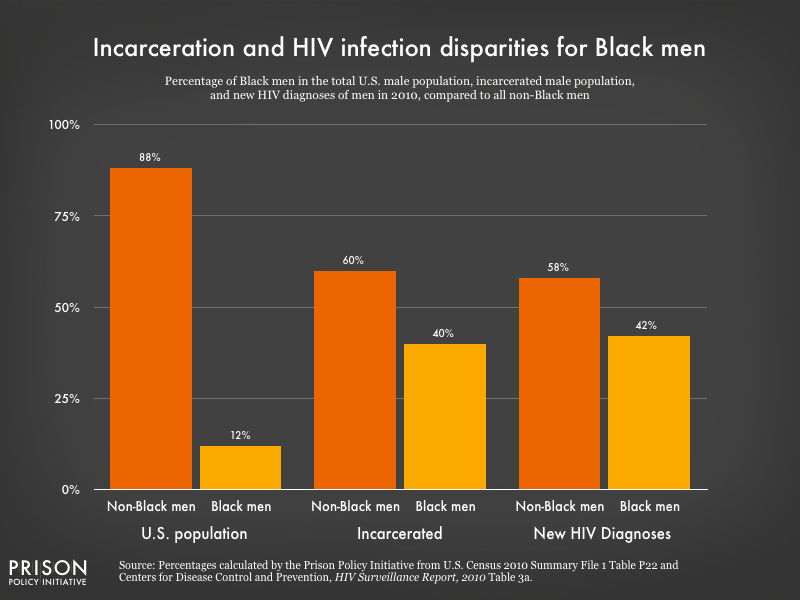

The bottom line is Black men are overrepresented in the number of people with HIV and in the number of people behind bars. Although Black men made up only 12% of the US male population at the time of the last Census, they accounted for over 40% of all incarcerated men and 42% of all newly reported HIV infections of men in the US.

The co-occurrence of high rates of HIV diagnoses and high rates of incarceration among Black men does not necessarily imply a causal relationship, but they work together to specifically burden the lives of Black gay and bisexual men — particularly in the South, where those rates are especially high. In a previous post, I wrote about the overrepresentation of Black women among new HIV infections, which some researchers have attributed to the high rates of incarceration of Black men.

The co-occurrence of high rates of HIV diagnoses and high rates of incarceration among Black men does not necessarily imply a causal relationship, but they work together to specifically burden the lives of Black gay and bisexual men — particularly in the South, where those rates are especially high. In a previous post, I wrote about the overrepresentation of Black women among new HIV infections, which some researchers have attributed to the high rates of incarceration of Black men.

These findings point to an alarming convergence of the population most burdened by HIV/AIDS and the population most disproportionately affected by mass incarceration. This intersection clearly warrants more attention, so I’m frustrated by the small number of studies dedicated to unravelling the connection between HIV, incarceration, and race.

The first analysis of incarceration history among Black MSM was conducted in 2014 and found evidence that there is a heightened lifetime risk of incarceration among Black MSM. Now, we need more nationally representative and rigorous studies to corroborate these findings. Villarosa argues that by incorporating the gay and bisexual Black men (and we would add, Black men who have experienced incarceration) into the literature and the larger understanding of HIV, we can improve outreach and preventative measures, increase the voice and standing of people of color in HIV/AIDS advocacy, and empower communities to demand change.

As Dr. Dybul states, “HIV is itself discriminatory, it preys on people who are left behind or marginalized by society.” Villarosa’s article highlights the stigma and marginalization of Black gay and bisexual men in the South, but it is important to note that this oppression is layered and systemic: Black MSM and Black men with HIV are also incarcerated at high rates, which only adds to the challenges they face when they return home to their communities.

After the Maine DOC solicited comments on the proposed changes to its visitation policies, we submitted a letter detailing why the elimination of in-person visits would hurt families.

by Lucius Couloute,

September 7, 2017

Due, in part, to our work on the video calling industry, most policymakers now recognize that in-person jail visits should not be replaced with glitchy, expensive, and impersonal video calls.

In states like Texas, California, and Illinois legislators have made it a point to ensure that incarcerated people get to see their loved ones face-to-face by prohibiting correctional facilities from eliminating in-person visits.

In Maine, however, the Department of Corrections (who holds the authority to set jail standards) is considering a move that would put them at odds with the national consensus: eliminating the requirement that Maine jails provide in-person contact visits, allowing them to instead provide video-only “visits”.

The DOC solicited comments on the proposed changes, so we submitted a letter detailing why the policy change would hurt families. You can read the full text of the letter, above. It concludes:

The DOC, on its own website, states that its mission is to “reduce the likelihood that juvenile and adult offenders will re-offend by providing practices, programs, and services which are evidence based.” Replacing in-person visits with video calling flies in the face of established evidence and punishes the families of incarcerated people who only wish to support their incarcerated loved ones. On behalf of incarcerated people looking to maintain their support systems, and their families, we urge the DOC to maintain in-person visits.

At a recent hearing, over 20 people testified against the proposed changes. We now await the final decision.

California legislators hold hearing on video calls and sharply criticize the dangers of banning in-person visits

by Bernadette Rabuy,

September 6, 2017

As we’ve explained, jails affect state prison outcomes. This might explain why California state legislators have been so concerned about the harmful trend of local jails replacing in-person visits with video calls. In the 2015-2016 legislation cycle, the California legislature approved SB 1157, which would have required jails to provide in-person visits, but Governor Brown vetoed the legislation. In his veto message, the governor asked the state regulatory body that sets jail visitation regulations, the Board of State and Community Corrections, to investigate the issue.

I didn’t realize this at the time, but SB 1157 was just the beginning of the struggle to protect in-person visits in California jails. After the veto, I learned that California legislators were planning an informational hearing at the state Capitol on video calls, and I was invited to testify on the Prison Policy Initiative’s research.

The timing worked out well. Days before the informational hearing, the Board of State and Community Corrections released proposed revisions to the jail visitation regulations. The regulations, which were later approved, prohibit jails from replacing in-person visits with video calls but exempt jails that had already eliminated in-person visits.

At the hearing, the legislators were colorful and adamant in their critiques of video calls. While the support from members of the public, legislators, and the press has been unanimous since we started our national campaign to protect in-person visits, it was still a rare and powerful sight to see legislators standing so strongly on the side of incarcerated people and their families. And the legislators pinpointed the dangers of banning in-person visits in a way that’s helpful for anyone in the country hoping to protect family visits:

- Eliminating in-person visits is contrary to reducing recidivism and supporting rehabilitation.

In 2011, California adopted Realignment in order to comply with a court order to reduce the state’s prison population. Realignment consists of shifting non-serious, non-violent, and non-sexual state prisoners from state prisons to county jails. As Senator Nancy Skinner pointed out, there was a secondary rationale for Realignment. California legislators and Governor Jerry Brown reasoned that imprisoning people in jails, which are generally closer to home, could lead to greater visitation. Because visits have been shown to reduce recidivism, in theory, imprisoning people in jails rather than prisons could reduce recidivism.

But as we’ve previously explained, there is no evidence that video calls have the same effect on recidivism as in-person visits. In fact, replacing in-person visits with video calls works against the goal of reducing recidivism because it can reduce visitation. In Travis County, Texas jails, banning in-person visits led the total number of visits to drop by 28% from September 2009 to September 2013. Thus, as state legislators aimed to increase visitation, county sheriffs were impeding visitation by leaving families with nothing more than low-quality video calls.

- As much as possible, states should not exempt counties from having to provide in-person visits.

As I previously noted, the Board of State and Community Corrections’ regulations prohibit jails from replacing in-person visits with video calls but exempt jails that had already decided to eliminate in-person visits. While Texas similarly exempted some counties from having to provide in-person visits, the key California legislators were more public about their belief that the exemption would let too many counties off the hook. In California, counties received exemptions for jails that were built without physical space for in-person visits and jails that were in the midst of construction or renovation that would culminate in only providing video calls. But some counties received exemptions when they were fully capable of providing in-person visits in a jail but had simply decided not to. In response to the exemption, Senator Skinner said,

I’ve got six that were built without visitation, so you know, maybe those are the six…that one could, perhaps, make a case for having difficulty…but, the first 10, it seems really hard to imagine why, when they already have that in-person space, the [regulations] would allow them to ban it.

Similarly, Assemblymember Shirley Weber pointed out,

I find it…difficult to digest that we would have facilities that have space, but would still refuse to have in-person visitations. What is the theory behind this?…There has to be some rationale…I assume the people who work in those facilities are… the leaders in the area [of] public safety and criminal justice…So what is the rationale for that?

Skinner and Weber were in disbelief that the exemption was crafted so broadly. The Board of State and Community Corrections defended the expansive exemption, saying that some counties built jails in recent years without physical space for in-person visits. When SB 1157 was introduced, these counties claimed that it would cost too much money to bring back in-person visits now that they had jails built without visitation rooms. But as the legislators pointed out, the Board of State and Community Corrections was exempting more than just those counties and it failed to provide any research or policy-based rationale for exempting counties that had the physical space to provide in-person visits.

Assemblymember Jones Sawyer rejected the idea that counties constructing or renovating jails in order to eliminate in-person visits should be exempted. Jones Sawyer explained that it wasn’t too late for the Board of State and Community Corrections to require these counties to change their plans,

I worked several years in the city of Los Angeles. I left as the director of real estate. I’ve actually built a jail in the city of L.A…. All of them can have [in-person] visitation in them…and you can require that…It can be done, and it can be done quickly, even on the end of construction.

The legislators agreed that the regulations were a half-hearted attempt to protect in-person visits.

- Because of the two-way relationship between state and local criminal justice systems, states should look for ways to influence harmful local criminal justice policies.

The state legislators were also upset that state money was being used in the construction and renovation of local jails that eliminated in-person visits. As Senator Skinner said, “The state is paying most of the bill for these county facilities…so in theory, the state should be able to make these decisions.” Senator Mitchell, the author of SB 1157, similarly expressed,

I’m very glad that the budget subcommittee chairs for public safety are here, and I hope that you will take [this] into account as we make future decisions about funding allocations for the constructions of jails…that we’re clear about what state policies, what state expectations they will adhere to because perhaps we should turn off the spigot.

The legislators expressed some support for local control of criminal justice policies, but they did not want to financially support a harmful trend that was working against the state’s goal of reducing recidivism. The legislators also felt that the Board of State and Community Corrections was fully aware of the legislators’ support for in-person visits since they approved SB 1157 with bipartisan, bicameral support.

The hearing was the most tense and lively visit to the California Capitol I’ve experienced. It was powerful to witness legislators so animated over an issue that primarily affects incarcerated people and their families, a population that is too often ignored. The legislators’ sharp analysis of the harm of banning in-person visits was also a reminder that this campaign should not exist on the fringes of the larger movement to end mass incarceration. Assemblymember Weber might have captured the urgent need to protect in-person jail visits best, “I feel like we’ve made some steps forward in this whole area of criminal justice, every time we seem to go forward, there seems to be some problem to drag us back. And some of these problems appear to be small, but they really have huge consequences.”

Update: In June, Governor Brown signed the 2017-2018 California budget, including AB 103, which statutorily requires jails to provide in-person visits rather than video calls. Like the approved regulations, the budget trailer bill exempts counties that had already decided to eliminate in-person visits. The bill is a step forward because it adds a statutory layer of protection for in-person visits and protects in-person visits in more California counties. The Board of State and Community Corrections has put the approved regulations on hold to ensure that the regulations conform with AB 103.

The co-occurrence of high rates of HIV diagnoses and high rates of incarceration among Black men does not necessarily imply a causal relationship, but they work together to specifically burden the lives of Black gay and bisexual men — particularly in the South, where those rates are especially high. In a

The co-occurrence of high rates of HIV diagnoses and high rates of incarceration among Black men does not necessarily imply a causal relationship, but they work together to specifically burden the lives of Black gay and bisexual men — particularly in the South, where those rates are especially high. In a