In some counties - like Multnomah County, Oregon - auditors are joining the movement to hold jails accountable.

by Wanda Bertram,

October 31, 2018

Jail reform is on the ballot next week in Multnomah County, Oregon, but it isn’t part of a popular initiative or gubernatorial campaign. It’s a key issue at stake in an unlikely, historically “boring” race: the race for County Auditor.

What could a County Auditor possibly do to reform criminal justice policy? Five years ago, the same question might have been asked about district attorneys or sheriffs. But as the public comes to understand the role that prosecutors, sheriffs and other local electeds can play in reversing mass incarceration, those offices are becoming centers of reform in some areas. The Auditor’s office could be next.

If you think of auditors as glorified bookkeepers, both of the candidates in Multnomah County’s runoff election would disagree. Candidate Scott Learn’s website says the Audit Office “needs to focus far less on informational reports…and far more on helping to improve the effectiveness of crucial county services.” He’s interested in auditing probation and parole services, the local juvenile detention center, and mental health services at the county jail.

Learn’s opponent, Jennifer McGuirk, says that “one of the Auditor’s most important responsibilities is deciding which programs to audit.” McGuirk, too, plans to audit the county’s jails. She was inspired to run after reports emerged of racist abuse in the jails, reports that the previous County Auditor declined to look into.

To be sure, Learn and McGuirk are departing from how auditors have traditionally done their jobs. County Auditors are mainly tasked with rooting out local agencies’ mismanagement of funds.

But to be clear: Abusive, inhumane treatment by criminal justice agencies is a misuse of funds. Jails receive public money (and quite a lot of it) for the purpose of “providing effective detention, rehabilitation, and transition services,” as the Multnomah County Sheriff’s website puts it. Human rights violations fall somewhat outside of this mission, so it’s logical that the County Auditor’s office should investigate.

With two reform-minded candidates neck-and-neck in this race, it’s clear that Multnomah County voters agree that justice reform should be a priority. Will your city or county be next?

Our criminal justice system isn’t just sending people from school to prison – it’s locking them out of education altogether.

October 30, 2018

It’s common knowledge that the U.S. criminal justice system funnels youth from schools to prisons – but what happens after that? How many people, for instance, are able to finish high school during or after prison? A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative breaks down the most recent data, revealing that incarcerated people rarely get the chance to make up the education they’ve missed.

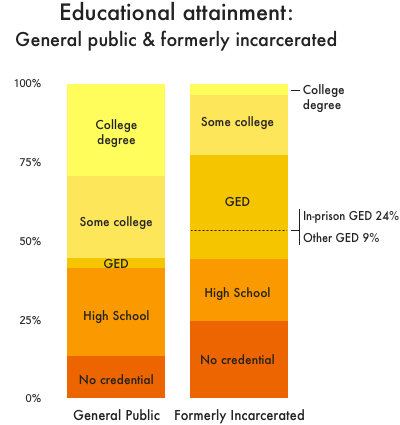

The data shows how incarceration, rather than helping people turn their lives around, cements their place at the bottom of the educational ladder:

- 25% of formerly incarcerated people have no high school credential at all – twice as many as in the general public.

- Formerly incarcerated people are most likely to finish high school by way of GED programs, missing the benefits of a traditional four-year education.

- Less than 4% of formerly incarcerated people have a college degree, compared to 29% of the general public.

The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is a staggering 27%, the Prison Policy Initiative previously found. This rate differs by education level. For those returning home from prison without educational credentials, it is “nearly impossible” to find a job:

- Formerly incarcerated people without a high school diploma or GED face unemployment rates 2 to 5 times higher than their peers in the general public. These rates differ by race and gender, ranging from 25% for white men to 60% for Black women.

- The number of “low-skill” jobs requiring only a high school credential has dropped since 1970, leaving many formerly incarcerated people with even fewer job prospects than ever before.

- Even as college degrees become critical to finding a job, most incarcerated people cannot access degree-granting programs, Pell Grants and federal student loans.

“We need a new and evidence-based policy framework that addresses K-12 schooling, prison education programs, and reentry systems,” report author Lucius Couloute concludes. He offers four far-reaching recommendations aimed at increasing access to educational opportunities, for both incarcerated people and youth at risk.

Today’s report is the third and final part of a new series from the Prison Policy Initiative, focusing on the struggles of formerly incarcerated people to access employment, housing, and education. Utilizing data from a little-known and little-used government survey, Couloute and other analysts describe these problems with unprecedented clarity. In these reports, the Prison Policy Initiative recommends reforms to ensure that formerly incarcerated people – already punished by a harsh justice system – are no longer punished for life by an unforgiving economy.

It’s become habit to consult prosecutors and victims during the release process. States should break that habit.

by Jorge Renaud,

October 25, 2018

While working on an upcoming report about how to shorten long prison sentences, I was disappointed to see that the same experts urging reform are reflexively endorsing part of the status quo. Criminal justice researchers are urging states to change how they consider release for individuals with lengthy prison sentences. However, these reformers continue to recommend that states solicit the input of prosecutors and survivors when making release decisions.

These recommendations reflect established practice rather than progressive policy. States should leave decisions about an individual’s release to professionals who understand that person’s behavior and needs.

Why should prosecutors have a role in the “mercy” process?

The deference shown to prosecutors reaches every aspect of the criminal justice system. Even the reformers who recommend consulting prosecutors on parole decisions and second-look sentencing, however, fail to explain why their involvement is needed in these post-sentencing processes. It strikes me as counterintiuitive that the official responsible for seeking someone’s lengthy sentence should be consulted about that person’s release, yet those recommendations continue.

For example, in the recently approved revision to the Model Penal Code, The American Law Institute recommends a “second-look” provision that would provide review and possible relief to incarcerated individuals who have spent at least 15 years in prison. However, it also recommends that “notice of the sentence-modification proceedings should be given to victims, if they can be located with reasonable efforts, and to the relevant prosecuting authorities.”

I found it almost impossible to find a policy that would mitigate the time a convicted individual must serve, or a parole decision to be made, where it is not recommended – and in some cases mandated – that the deciding officials give prosecutors a chance to weigh in:

- When asked what “sources of input” were considered in release decision-making, 34 of 38 respondents from state parole decision-making bodies said “district attorneys.”

- In 12 of the 24 states profiled by the Robina Institute, state parole decision-making bodies must notify the prosecuting attorney when an individual is being considered for parole; one state mandates a prosecutor’s input must be solicited when an individual with a life sentence is being considered for parole; and 11 states require that the decision-making bodies provide information to the prosecutors upon their request.

This deference toward prosecutors is uncalled for, especially when the only information prosecutors can provide relates to the crime – not to the more important question of whether the person under review has undergone a transformation while incarcerated. Prosecutors are particularly unfit to determine whether individuals they have not seen in years or decades still pose a threat to public safety. As Prof. R. Michael Cassidy at Boston College Law School puts it in a forthcoming paper, “prosecutorial input at parole hearings is likely to accomplish very little beyond either grandstanding for the media or intimidating the parole board into being risk-averse in close cases.”

Recall that between 95 and 97% of all felony convictions are the result of plea bargains between defendants and prosecutors. In offering and accepting a plea bargain, a prosecutor determines when the defendant may be eligible for release and accepts that possibility in exchange for the certainty of a conviction. Whether individuals thus convicted are actually released at that first eligibility date should not be the prosecutor’s concern, only that of the parole board, commutation official, or judge taking a second look.

Finally, there is a strong argument that prosecutorial overreach is responsible for explosive prison growth, both in the numbers of individuals in prison and the astonishingly long sentences many of them have. Although there has been movement toward a progressive prosecutorial approach, exemplified by D.A. Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, it remains to be seen if that approach extends beyond those charged with drug possession and non-violent property crimes. In any case, states should reconsider their choice to include prosecutors in the “mercy” process, given that the punitiveness of prosecutors has created a prison boom.

Should the release process include the views of survivors?

The voices of survivors have become a welcome part of criminal justice proceedings, as they should be. Survivors have an intimate stake in what happens after individuals are sent to prison. But this valuable perspective should be channeled towards advising prison programming, not release. The decision to release an individual should be informed exclusively by an understanding of that individual’s behavior and needs – information that survivors, like prosecutors, simply do not have.

Many people assume that all survivors of violence fit their image of a bereaved family member angrily demanding that a convicted individual be sentenced to life in prison. While many survivors do ask for lengthy prison terms for their attackers, a more accurate picture is presented by a 2016 national survey of survivors of violence commissioned by the Alliance on Safety and Justice. The survey revealed that:

- 60% of victims preferred shorter prison sentences and more spending on prevention and rehabilitation to longer prison sentences;

- Victims were three times more likely to prefer holding people accountable through options other than prison, such as rehabilitation, mental health and drug treatment, and community supervision;

- Victims were also three times more likely to believe that prison makes people more likely to commit crimes than to rehabilitate them;

- And perhaps most poignantly, seven out of 10 victims of violent crimes preferred that prosecutors focus on solving neighborhood problems and stopping repeat crimes through rehabilitation, even if that meant fewer convictions and prison sentences.

To that end, survivors are uniquely positioned to push state departments of corrections to implement programming that focuses on transformation – on nourishing remorse that is grounded not in shame, but in recognition of harm and responsibility. Survivors’ rights groups should be consulted when policymakers are deciding which programs to offer to incarcerated individuals to prepare them for their eventual release.

However, the decision to release an incarcerated individual, or to mitigate that person’s sentence, should be made by professionals with an understanding of that person’s behavior and needs. It should also include input from those who have been in contact with those individuals throughout their incarceration.

Rather than critique the involvement of survivors outright, reformers have proposed meaningless compromises that effectively insult survivors. Reformers suggest, paradoxically, that survivors be allowed to speak at parole hearings but not to recommend approval or denial of parole. That ignores the emotional weight any testimony of a survivor of violence will have on decision makers.

Restorative justice may find a place in our criminal justice system, allowing survivors of violence to heal in ways besides demanding long prison terms for those who have wounded them. Prosecutors may realize that a truly progressive approach means not seeking unimaginably long sentences rooted in retribution. Until then, neither prosecutors nor survivors should have a meaningful voice deciding whether or not to deny freedom to an individual who has served a lengthy sentence.

So why does Trump continue to endorse stop-and-frisk?

by Alexi Jones,

October 12, 2018

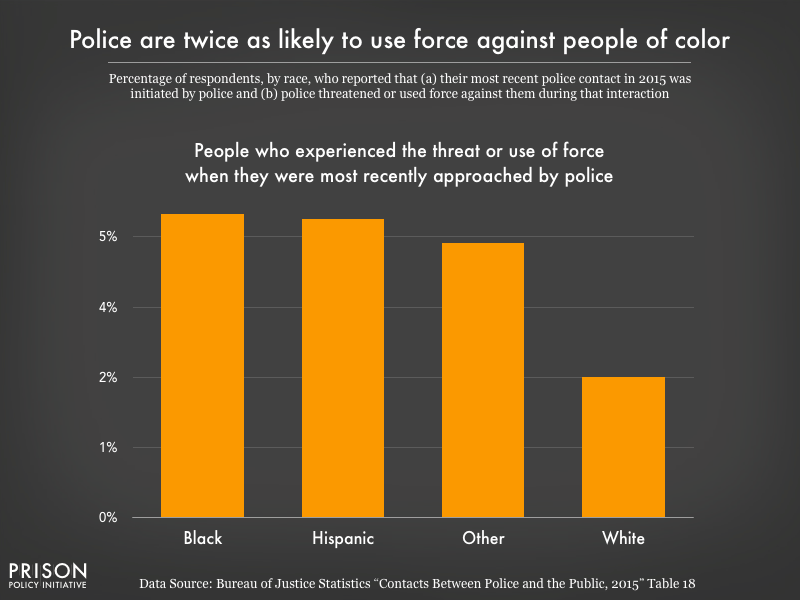

President Trump is again encouraging Chicago police to use stop-and-frisk – a policy that allows police officers to stop citizens for virtually any reason – even as new government data reminds us why such policies can be disastrous for people of color. Just days after Trump endorsed stop-and-frisk in Chicago, the Bureau of Justice Statistics released its new report on interactions between police and the public, using survey data from 2015. The report reminds us that police stops and use of force are already racially discriminatory, with predictable consequences for public trust of the police.

The report reveals:

- Black residents were more likely to be stopped by police than white or Hispanic residents, both in traffic stops and street stops.

- Black and Hispanic residents were also more likely to have multiple contacts with police than white residents, especially in the contexts of traffic and street stops. More than 1 in 6 Black residents who were pulled over in a traffic stop or stopped on the street had similar interactions with police multiple times over the course of the year.

- When police initiated an interaction, they were twice as likely to threaten or use force against Black and Hispanic residents than white residents.

These racial disparities in policing have predictable effects on public trust of the police:

- There were marked racial differences in perceptions of police behavior and legitimacy of police stops. Less than half of Black and Hispanic residents stopped on the street by police thought the stop was legitimate, while two-thirds of white residents did. And 60% of Black residents who experienced the threat or use of force perceived the force as excessive, compared to 43% of white residents who experienced force.

- White residents were more likely than Black, Hispanic, and residents of other races to initiate contact with police – for example to report a crime, a non-crime emergency, or to seek help for another reason. 46% of white residents who had contact with police initiated the contact, compared to less 37% of Black residents.

The report’s findings related to the use of force are particularly relevant to the national conversation about policing. The scale of police use of force alone is overwhelming. Nearly 1 million U.S. residents age 16 or older experienced the threat or use of force by police in 2015. And the people experiencing threats or use of force by police were disproportionately Black and Hispanic.

Previous local studies suggest that stop-and-frisk is particularly discriminatory. In 2010, near the peak of the city’s use of stop-and-frisk, Black residents in New York City were 8 times more likely to be stopped by the police than white residents and 11 times more likely to be frisked. And in 2011, New York City police reported using force in 23% of stops of Black and Latino residents, but in only 16% of stops of white residents.

Given these past and current policing disparities, it is not surprising that Black and Hispanic communities are less trusting of police. As the BJS report shows, Black and Hispanic people are less likely view the use of force as legitimate and less likely to seek help from police compared to white people. This is in line with Pew’s 2016 finding that only about a third of Black Americans believe that police treat racial and ethnic groups equally and that police in their community used the appropriate amount of force, compared to three-quarters of white Americans.

These disparities undermine the legitimacy of law enforcement and create a two-tiered policing system; moreover, they compromise public safety. If residents do not trust the police, they are less likely to report crimes and cooperate with police investigations. So despite what Trump says, stop-and-frisk remains as bad a policy as ever. Police should be looking to address these disparities, not implementing a policy that exacerbates them.