We've had an incredibly productive year. In our new annual report, we share the highlights.

by Peter Wagner,

November 29, 2018

We just released our 2017-2018 Annual Report, and I’m thrilled to share some highlights of our work with you. We’ve had an incredibly productive year, releasing 11 major national reports, exposés, legislative briefings, and guides for advocates and journalists.

There are a few successes I’m particularly proud of:

But that’s not all. In our highly-skimmable annual report, we review our work on all of our issues over the last year. Thank you for being a part of our successes over the last year. We are looking forward to working with you in the year to come.

by Peter Wagner,

November 21, 2018

Mujahid Farid, the founding organizer of a campaign to reduce the number of elderly and infirm people in New York State prisons, died yesterday at 69. His Release Aging People in Prison campaign in New York State – known as the RAPP Campaign – was critical:

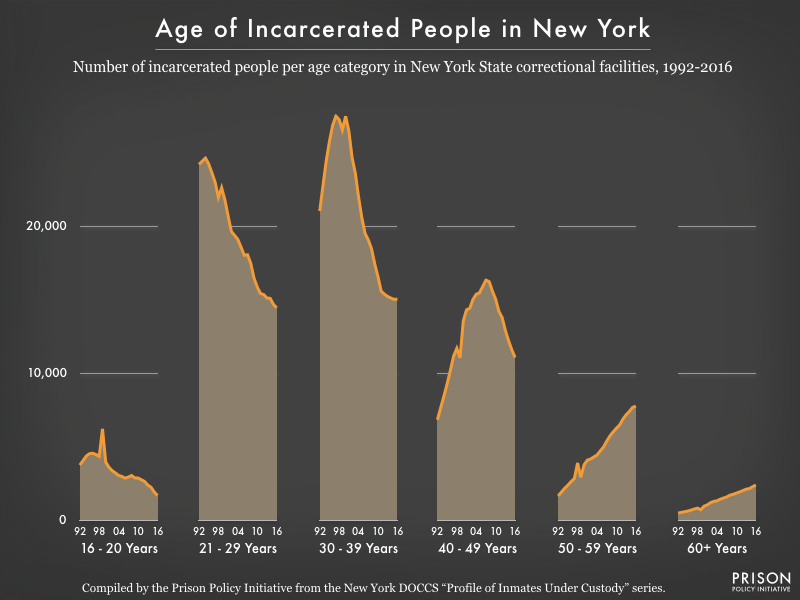

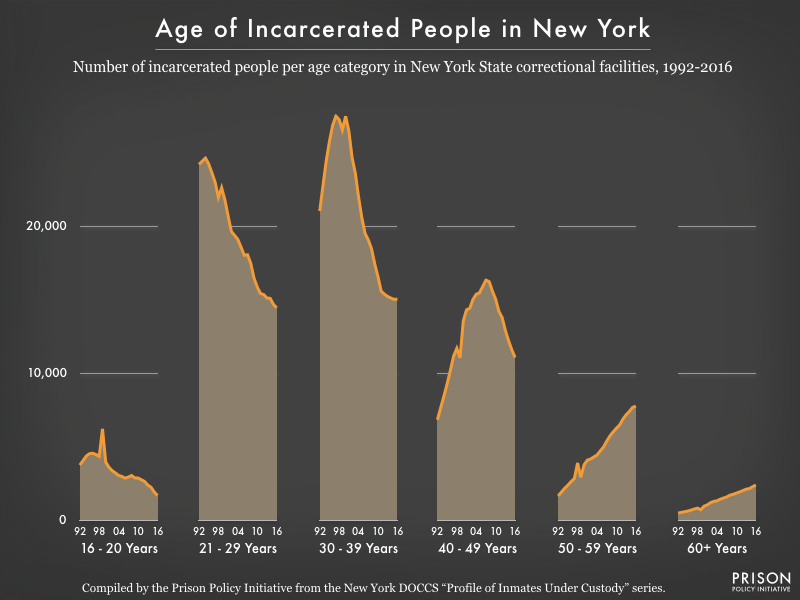

Release Aging People in Prison/RAPP works to end mass incarceration and promote racial justice by getting elderly and infirm people out of prison. The number of people aged 50 and older in New York State, where RAPP was founded, has doubled since 2000; it now exceeds 10,000—about 20% of the total incarcerated population. This reflects a national crisis in the prison system and the extension of a culture of revenge and punishment into all areas of our society.

I got to spend some time with Farid at a conference in 2014, and offered to use our knowledge of the New York State prison system’s data to help visualize what Farid already knew: that New York’s much-heralded prison population decline was confined solely to the population of people under 50 and the elderly were being left behind. We’ve updated that graph and analysis a few times, most recently just three weeks ago:

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

And at that same conference in 2014, Leah Sakala and I shot a short interview with Farid when the RAPP Campaign was just starting:

Each summer since, I’d see Farid at that same conference, and checking in with him was always a highlight. He’ll be greatly missed. Thank you for your work, Mujahid Farid.

Clemency isn't the only way for governors and legislators to show mercy. Our report provides a roadmap with several options.

November 15, 2018

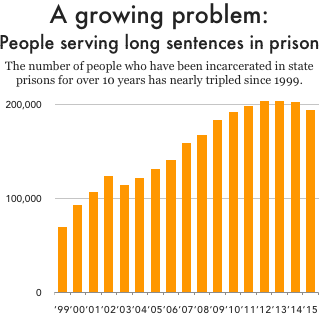

More than 200,000 people in state prisons today have been there for a decade or more. But even when governors and legislators want to give these individuals a “second chance,” they’ve had no handbook for doing so – until now.

In a new report, the Prison Policy Initiative presents eight ways for states to help people serving excessive prison sentences finally go home. “Clemency is far from the only option,” said author Jorge Renaud. “We don’t have to invent new strategies – there are many out there that are vastly underused.”

His report Eight Keys to Mercy gathers examples of innovations from around the country, and presents these strategies as a slate of options, including:

- Ways to fix broken state parole systems, such as presumptive parole;

- Solutions for states where few people are eligible for parole, such as second-look sentencing;

- Common-sense reforms, such as expanding good time, to support people already working hard to get out (and stay out) of prison.

The report’s eight recommendations also include:

- Visual aids and explainers, including a detailed guide to present-day parole systems;

- Instructions for implementing reforms while avoiding common pitfalls;

- Fact sheets for all 50 states, meant to help policymakers and journalists quickly assess the problem where they live.

Mercy doesn’t begin and end with the governor. But in most states, the systems designed to help people leave prison – such as parole, good time and compassionate release – are skewed towards keeping them inside. “This can’t continue to be the norm,” said Renaud. “People should not spend decades in prison without meaningful opportunities for their release.”

Read the full report and recommendations here: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/longsentences.html

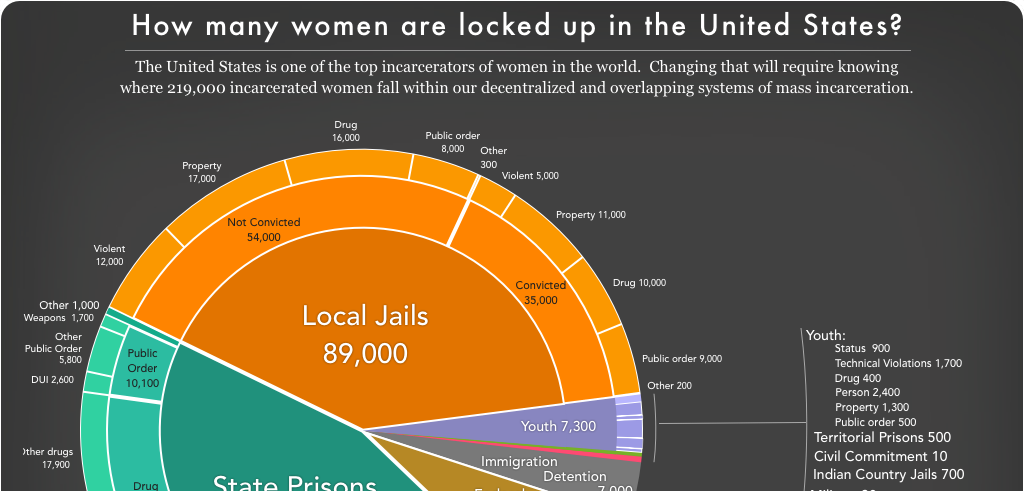

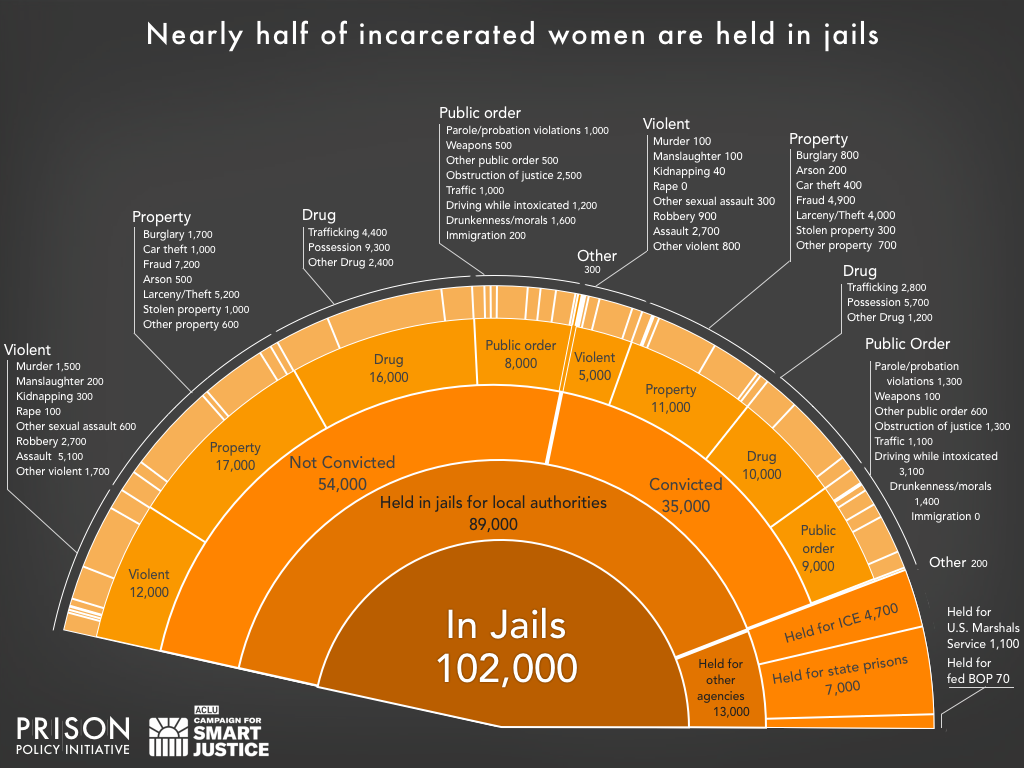

The report includes a new, data-rich visualization of women in jails, highlighting a critical area for criminal justice reform.

November 13, 2018

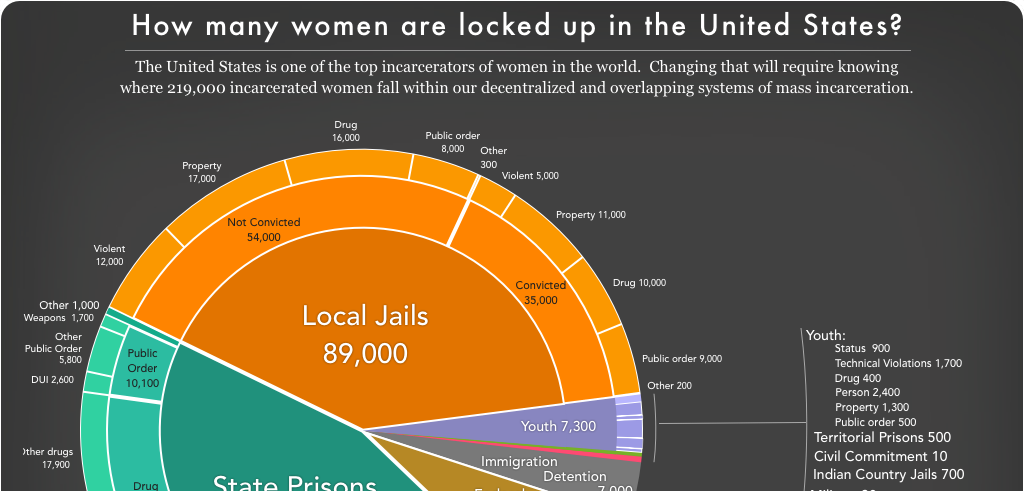

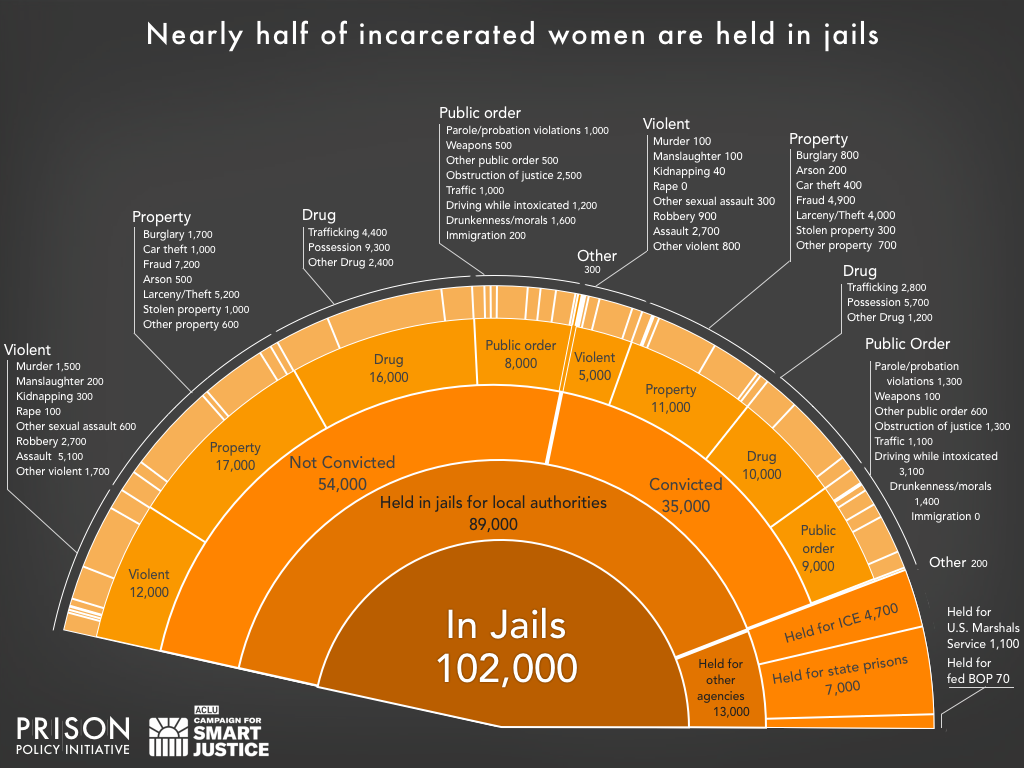

Women in the U.S. experience a starkly different criminal justice system than men do, but data on their experiences is difficult to find and put into context. In a new report produced in collaboration with the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice, the Prison Policy Initiative fills this gap in the data with a rich visual snapshot of how many women are locked up in the U.S., where, and why.

In Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2018 (a detailed update to the inaugural 2017 version), Legal Director Aleks Kajstura pieces together data from the country’s fragmented systems of confinement, producing a detailed “big picture” visualization as well as a separate close-up view of women in local jails.

Kajstura’s analysis reveals that:

- 56% of women in prisons or jails are there for drug or property offenses, compared with approximately 40% of the general incarcerated population (which is almost entirely male).

- 7,000 immigrant women are in confinement every day awaiting deportation or an immigration hearing.

- 54,000 women are behind bars every day without a conviction, typically because they cannot afford money bail.

- While 219,000 women are behind bars every day, over 1 million are on probation, suggesting that probation reform is also a women’s issue.

“With this big-picture view, it’s easier to see why many state-level reforms unintentionally leave women behind,” Kajstura said. Her analysis particularly underscores the need for local reforms to county jails:

- Incarcerated women are far more likely than men to be held in local jails, both before trial and while serving their sentences.

- Of all immigrant women held for ICE, 4,700 are not in detention centers, but “rented” beds in local jails.

- 80% of women in jail are mothers, and most are the primary caretakers of their children.

- Mental health care is notoriously bad in jails, where suicide rates are literally off the charts.

While states vary widely in how many women they put behind bars, every single U.S. state outranks most independent countries on women’s incarceration, as we found in June 2018 – making reform a moral necessity in every state. Kajstura calls her analysis “the foundation for reforming the policies that lead to incarcerating women in the first place.”

See the full data visualization and report: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2018women.html

Despite recent positive reforms, New York's elderly prison population continues to grow.

by Maddy Troilo,

November 1, 2018

Several years ago, we reported on the elderly prison boom in New York; I thought it was time to update our analysis to examine the impact of recent reforms to the state’s Parole Board.

First, for context, a brief summary of New York’s parole reforms: After sustained effort by advocacy groups, the New York State Board of Parole revised the guidelines that shape their practices–long documented to be harmful to incarcerated people and their families–in September 2016. In June of that year, a campaign to change the composition of the Parole Board was successful, and Governor Cuomo appointed new Parole Commissioners with more diverse backgrounds and no history of abusing the position.

Advocates hoped these changes would increase the rate at which aging and elderly people in New York prisons are granted parole, and alleviate some of the “graying” of the state’s prisons. That happened, to a degree: this year, Release Aging People in Prison (RAPP) found that the Parole Board’s release rates have increased for people 50 or older from 24% to 40%. That change marks meaningful progress, but was it enough to reverse the growth in New York’s aging and elderly prison population?

Unfortunately, no. I found that even as the incarceration rate for all other age groups declines, the number of people age 50 and over incarcerated in New York continues to rise rapidly:

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

As we showed in 2015, this rapid increase must be the result of decisions about release, because the number of aging and elderly people admitted to New York prisons only increased slightly. That’s certainly still the case, but I can’t update our graph of the commitment data because the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision hasn’t published any new data on people’s age at admission since 2014.

New York needs to do better; aging and elderly people shouldn’t be left behind as younger people continue to benefit from the state’s overall decline in incarceration. The state can begin by making these further changes:

- Seat more people on the board to combat understaffing and dismissing those who abuse and misuse their positions

- End the use of the “nature of the crime” as a factor in parole decisions

- Give more weight to people’s accomplishments while incarcerated

- Institute a meaningful presumption of release at first eligibility

- Acknowledge the fact that elderly people pose no substantial risk to public safety.

The new reforms are important progress, but much more needs to be done. For more information on the campaign to improve the New York Parole Board, see RAPP’s report New York State Parole Board: Failures in Staffing and Performance.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.

Since 1992, the number of people age 50 and older incarcerated in New York state prisons has steadily increased, while the populations of every other age group have declined dramatically.