The Prison Policy Initiative submits a comment letter calling on the USPS to stop rounding up postage costs and to remember that low-income incarcerated people are reliant on the postal service for communication.

by Peter Wagner,

October 29, 2019

Today, the Prison Policy Initiative submitted a comment letter to the regulatory agency that oversees the Postal Service’s rates. The Postal Service is proposing to round the price of a first class stamp up to the nearest 5 cents.

Our objection is not to the specific rate charged, but to the policy of rounding up to the nearest nickel. We specifically objected to the Postal Services argument that the rounding is appropriate because the annual impact on the average “household” is small. In our nine-page letter, we explain:

- Why the 2.3 million people incarcerated in the U.S. are disproportionately reliant on the Postal Service for communication.

- How much mail the typical incarcerated person sends (in perhaps the first ever national estimate of how many stamps incarcerated people purchase).

- Why the Postal Service is obligated to serve all people, not just “households.”

- Just how little income incarcerated people have, and how many hours of prison labor it would take to pay for a 3 cent rate increase caused by the Postal Service’s rounding policy.

- Why it is inappropriate to propose a rule that disproportionately impacts incarcerated people — who do not have ready access to the Internet — and only allow a narrow two week comment period.

In our letter, we explain that incarcerated people and their families represent a constituency that is uniquely dependent on letter mail sent via the U.S. Postal Service. We argue that the Postal Service’s five-cent rounding policy imposes substantial negative effects on this constituency. Unless the Postal Service is willing to create a new classification to provide reduced rates for mail sent by or to an incarcerated person, the needs of incarcerated customers should be accounted for in determining how rates are calculated.

The five-cent rounding policy has already come under fire from the federal courts. In September, a federal court rejected the Postal Service’s rationale for its January 2019 rate increase to 55 cents. (The Postal Service’s data showed that a stamp should cost 52 cents in 2019, but their new rounding rule made a stamp cost 55 cents in 2019.) Unfortunately, despite the Postal Service’s loss in court, the proposal for rates in 2020 invents a new flawed rationale to justify the discredited rounding policy. (Without the rounding policy, stamp prices would probably be 52 or 53 cents in 2020.)

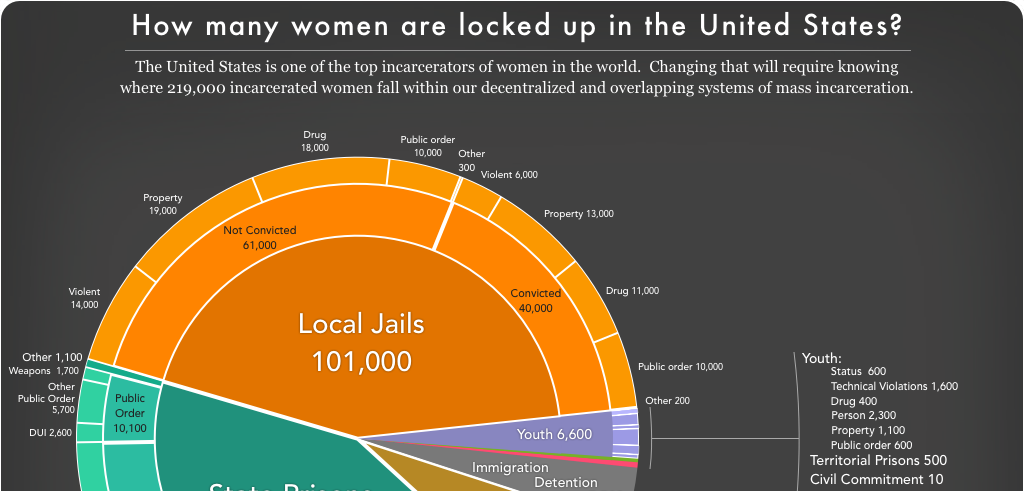

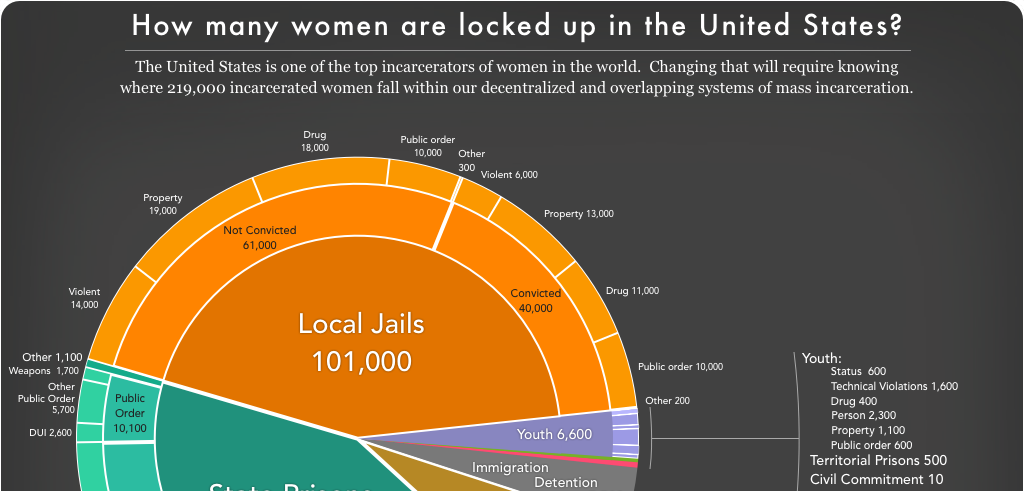

The report highlights the need for reforms to local jails, which now hold more women than state prisons do.

October 29, 2019

A report released this morning by the Prison Policy Initiative and the ACLU Campaign for Smart Justice presents the most recent and comprehensive data on how many women are locked up in the U.S., where, and why.

Women in the U.S. experience a dramatically different criminal justice system than men do, but data on their experiences is difficult to find and put into context. The new edition of Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, which the Prison Policy Initiative and ACLU have published every year since 2017, fills this gap with four richly-annotated data visualizations about women behind bars.

“Producing this big-picture view of incarcerated women helps us see why many recent criminal justice reforms are failing to reduce women’s incarceration,” said report author Aleks Kajstura. Most importantly, the new report underscores the need for reforms to local jails:

- More incarcerated women are held in local jails than in state prisons, in stark contrast to incarcerated men, meaning that reforms that only impact people in prison will not benefit them.

- The number of women in local jails grew between 2016 and 2017 — a trend that reflects counties’ growing reliance on jails to solve social problems.

- Women convicted of criminal offenses are more likely than men to be serving their sentences in local jails, where healthcare and rehabilitative programs are much harder to access than in prisons.

- On any given night, 4,500 immigrant women are held for ICE in local jails — over half of the 7,700 women held in immigration detention.

The report goes on to explain why 231,000 women are locked up in the U.S.:

- 73% of women in prisons and jails are locked up for nonviolent offenses, in contrast to only 57% of all people in prisons and jails (who are almost entirely men).

- 10% of girls in the juvenile justice system — compared to only 3% of boys — are held for status offenses like running away, truancy, or “incorrigibility,” which would not be crimes if committed by adults.

- 27% of women in prisons and jails are locked up for violent offenses, including acts of violence committed in self-defense.

Beyond presenting new data, Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019 also reviews the existing literature on women’s incarceration, including the Prison Policy Initiative’s prior research on gender disparities in police contact, women’s access to reentry services after incarceration, and the incomes of women in prisons and jails.

We've had an incredibly productive year. In our new annual report, we share the highlights.

by Peter Wagner,

October 17, 2019

We just released our 2018-2019 Annual Report, and I’m thrilled to share some highlights of our work with you. We’ve had an incredibly productive year, releasing 10 major national reports and 27 research briefings, as well as doubling down on our strategic communications work and making our website an even better tool for researchers and advocates.

There are a few successes I’m particularly proud of:

- Calculating the first national estimates of homelessness among people who have been to prison, revealing that formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public.

- Releasing a landmark report on the prison and jail phone industry, which sparked a wave of news coverage, spurred multiple counties to action, and helped push the issue of prison phone justice onto the platforms of multiple presidential candidates.

- Launching a campaign to help counties uncover the root causes of jail overcrowding rather than building new jail space, using our new report Does our county really need a bigger jail?

- Helping Washington and Nevada become the fifth and sixth states to end prison gerrymandering. (And momentum is building: nine other states considered bills to end prison gerrymandering this year.)

- Publishing a groundbreaking 50-state report comparing parole release systems — a first-of-its-kind guide to understanding parole and how it works in every state.

But these highlights barely scratch the surface of what we’ve accomplished this year. See our highly-skimmable annual report for a review our work on all of our issues over the last year. I’m honored that you were a part of these successes, and I’m looking forward to working with you in the year to come.

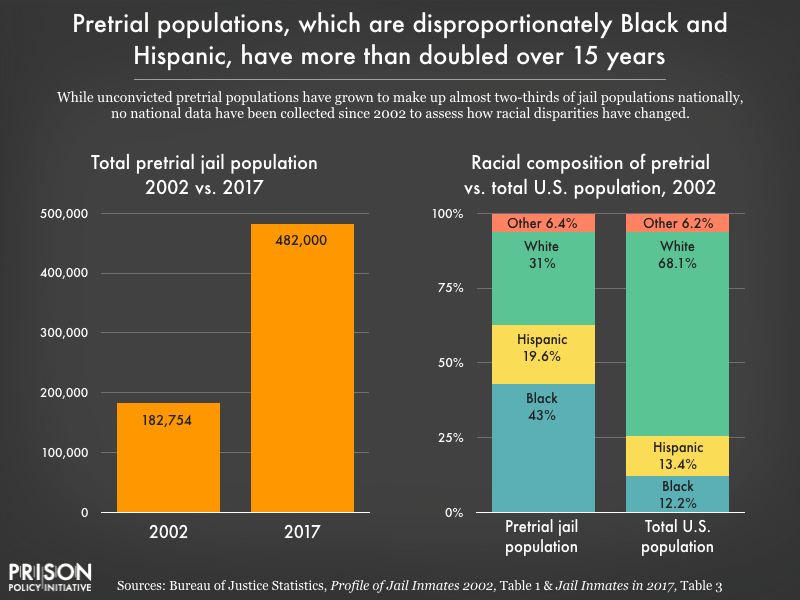

The government hasn’t collected national data on the race or ethnicity of people awaiting trial in jail since 2002. We review the academic literature published since then to offer a more current assessment of racial disparities in pretrial detention.

by Wendy Sawyer,

October 9, 2019

Being jailed before trial is no small matter: It can throw a defendant’s life into disarray and make it more likely that they will plead guilty just to get out of jail.1 As advocates bring national attention to these harms of pretrial detention, many places – most recently New Jersey, California, New York, and Colorado – have passed reforms intended to dramatically reduce pretrial populations.

But it’s not enough to simply bring pretrial populations down: Another central goal of pretrial reform must be to eliminate racial bias in decisions about who is detained pretrial and who is allowed to go free. Historically, Black and brown2 defendants have been more likely to be jailed before trial than white defendants. And recent evidence from New Jersey and Kentucky shows that while some reforms have helped reduce pretrial populations, they’ve had little or no impact on reducing racial disparities.

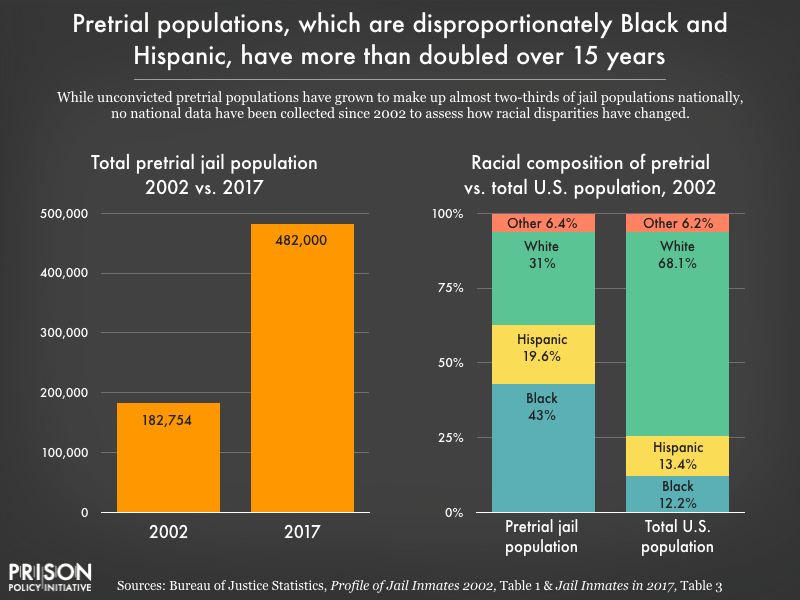

As of 2002 (the last time the government collected this data nationally), about 29% of people in local jails were unconvicted – that is, locked up while awaiting trial or another hearing. Nearly 7 in 10 (69%) of these detainees were people of color, with Black (43%) and Hispanic (19.6%) defendants especially overrepresented compared to their share of the total U.S. population. Since then, pretrial populations have more than doubled in size, and unconvicted defendants now make up about two-thirds (65%) of jail populations nationally. With far more people exposed to the harms of pretrial detention than before, the question of racial justice in the pretrial process is an urgent one – but the lack of national data has made it hard to answer.

While pretrial jail populations have grown to make up almost two-thirds of jail populations nationally, and Black and Hispanic defendants were overrepresented in the 2002 population, no national data have been collected since then to assess how racial disparities may have changed.

While pretrial jail populations have grown to make up almost two-thirds of jail populations nationally, and Black and Hispanic defendants were overrepresented in the 2002 population, no national data have been collected since then to assess how racial disparities may have changed.

So what, exactly, is the state of racial justice in pretrial detention? And how can advocates assess racial justice in their county or state? What data do they need, and where can they find it? This briefing reviews findings from recent studies of racial disparities in pretrial decisions – including both national and more geographically-limited analyses – and then suggests sources for further research to understand and address the problem.

To assess the state of racial justice in pretrial detention since the last national survey was conducted nearly 20 years ago, I reviewed more recent academic literature – studies that utilize other data sources and offer more nuanced analysis.

Overall, the available research suggests that:

- In large urban areas, Black felony defendants are over 25% more likely than white defendants to be held pretrial.

- Across the country, Black and brown defendants are at least 10-25% more likely than white defendants to be detained pretrial or to have to pay money bail.

- Young Black men are about 50% more likely to be detained pretrial than white defendants.

- Black and brown defendants receive bail amounts that are twice as high as bail set for white defendants – and they are less likely to be able to afford it.

- Even in states that have implemented pretrial reforms, racial disparities persist in pretrial detention.

National data is limited and outdated

Only one publicly-accessible study uses a nationally representative sample to measure pretrial detention status by race: the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (SILJ), which was last conducted in 2002. Considering that jails and policing practices have changed significantly since 2002, an update to this dataset – now slated for 2021 – is long overdue.

Since 2002, national studies have been limited to felony cases in large urban counties. These studies are based on the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ (BJS) State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS), data which were last collected in 2009. The data include both demographic and case characteristics for each defendant, allowing researchers to control for legally-relevant factors like offense type, number of arrest charges filed, prior criminal record, and whether the defendant had failed to appear in court before. While BJS’ own publications based on this dataset (the Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties series) do not provide a breakdown of pretrial detention by race or ethnicity, some academic researchers have used it for that purpose. (For a full list of their studies, see the appendix to this article.)

These national studies of felony cases in large counties generally conclude that the direct impact of race on pretrial decisions is weak, but that racial bias acts cumulatively to affect outcomes, and indirectly via factors like ability to pay for bond or a private attorney. McIntyre & Baradaran’s analysis of 1990-2006 SCPS data concludes that Black defendants are over 25% more likely to be held pretrial than white defendants. The most recent SCPS data, from 2009, supports that finding: Even after controlling for age, gender, and a number of conceivably legally-relevant factors (most serious charge, prior arrests, etc.), Dobbie & Yang (2019) find that over half (58%) of the 39 sampled counties had higher rates of pretrial detention for Black defendants than for white defendants. In 5 counties, the unexplained racial gap was over 20%.

More recent, but geographically-limited, studies help fill in the gaps

More recent analyses shed further light on racial justice in pretrial decision-making, even though their samples are not nationally representative. I looked at 16 of these more geographically-limited studies, with subjects ranging from federal drug cases in the Midwest to misdemeanor cases in Harris County (Houston), Texas. In all, they include samples from 11 states spread across the U.S., and major cities including New York City, San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Miami.

Of course, no single estimate of racial disparity in pretrial detention will apply to all counties nationwide. In the studies I reviewed, the racial gap in pretrial detention between Black and white defendants ranges widely, from about 10% to 80% depending on the study and jurisdiction (that is, the county or city).

However, these studies most frequently confirm that unexplained racial disparities continue to plague the pretrial process.3 Throughout the literature, researchers report that rates of pretrial detention and receiving financial conditions of release (i.e. money bail) are consistently higher for Black and Latinx defendants (and often Native American defendants, when they are included in the analysis). Bail bond amounts, too, are consistently higher for Black and brown defendants, even though they are less able to afford money bail. Rates of release on recognizance or other nonfinancial conditions of release, such as pretrial supervision, are likewise lower for Black and brown – versus white – defendants. Furthermore, the studies that included sex and age in their analysis found that young Black males face the greatest disadvantages.

Specifically, these studies report significant racial disparities, such as:

- Most of these studies find that Black and brown defendants are 10-25% more likely to be detained pretrial or to receive financial conditions of release.

- Median bond amounts, when compared, are often about $10,000 higher for Black defendants compared to white defendants. In at least one study, the median bond set for Black defendants was double the median bond set for white defendants.

- The most recent analyses of racial disparities in pretrial detention – assessing the effects of reforms in New Jersey and Kentucky – show that pretrial assessment tools have not reduced these disparities as much as advocates hoped. After New Jersey essentially ended the use of money bail for most defendants in 2017, the total pretrial population dropped significantly, but the racial composition of the pretrial jail population changed very little. And in Kentucky, the racial disparity in pretrial release rates actually worsened after the state enacted a law requiring the use of a pretrial assessment tool.

Advocates may be able to find data about their local jails

Of course, county or city jail administrators may collect and maintain data on the racial/ethnic composition of their pretrial populations. Advocates in some jurisdictions may be able to request data about their own local pretrial jail populations, which they can compare with the overall local population for a simple measure of racial disparity. Such a comparison, however, will exclude other relevant characteristics (such as seriousness of offense or past failures to appear in court) and won’t identify what stage(s) of pretrial decision-making are affected by race (such as the decision to set a money bail amount, or how high bail was set). Nevertheless, even a crude estimate of racial disparity in local pretrial detention can help advocates draw attention to the issue and raise important questions with decisionmakers.

Where to look next for more data

Jailing Black and brown pretrial defendants more often than white defendants isn’t just unfair; it also contributes to racial disparities later in the justice process. But in order to solve this problem, local advocates and policymakers need current data about who is held pretrial in their counties and states. And in order to identify broader patterns in pretrial decision-making, we need more data at the national level as well.

Until the Bureau of Justice Statistics updates its Survey of Inmates in Local Jails – which, unfortunately, is not guaranteed to happen on schedule in 2021 due to chronic underfunding – advocates and policymakers must rely on independently-produced local studies. Academic researchers (including those referenced in this briefing) have already developed models for these local studies.

In places where there appears to be little or no data published about racial disparities in the pretrial process, advocates can partner with local academic institutions or ask state Statistical Analysis Centers for assistance. Several large-scale projects led by non-governmental organizations are also actively working to assist local jurisdictions in using their data to inform policy changes that will reduce unnecessary incarceration. For example, the MacArthur Foundation’s national Safety and Justice Challenge supports initiatives in 52 jurisdictions across the U.S. to reduce the misuse and overuse of jails. And Arnold Ventures recently launched the National Partnership for Pretrial Justice, advancing a variety of pretrial justice projects across 35 states. Measures for Justice is developing a broad, publicly-accessible database of county criminal justice data; currently it offers data from 6 states, with data from 14 more states expected in 2020. And of course, community bail funds across the country have been collecting data as they bail low-income defendants out of jail – no strings attached – and reporting high success rates that underscore just how unnecessary money bail is. These kinds of resources can help local advocates and future researchers find the data they need to measure racial disparities in pretrial justice processes, and work to eliminate them.

See the Appendix for a list of all of the sources reviewed for this briefing, with links and summaries of their findings related to racial disparities in pretrial detention.

Footnotes

While pretrial jail populations have grown to make up almost two-thirds of jail populations nationally, and Black and Hispanic defendants were overrepresented in the 2002 population, no national data have been collected since then to assess how racial disparities may have changed.

While pretrial jail populations have grown to make up almost two-thirds of jail populations nationally, and Black and Hispanic defendants were overrepresented in the 2002 population, no national data have been collected since then to assess how racial disparities may have changed.