When the only way to get necessities in prison is to buy them from a single retailer, exploitation is the result.

by Wanda Bertram,

November 14, 2019

As John Oliver explained in a recent episode of Last Week Tonight, people in prison are consumers too: Incarcerated people must pay for basic necessities such as phone calls, soap, and medicine, to say nothing of “luxury” items such as books. But how are consumer rights and protections different for people behind bars, and what can be done to protect these consumers from exploitation?

The Hastings Race and Poverty Law Journal has just published an article by Prison Policy Initiative volunteer Stephen Raher, presenting a comprehensive survey of consumer law issues in prisons and jails. Raher will speak about his article, The Company Store and the Literally Captive Market, at this weekend’s Consumer Rights Litigation Conference, sponsored by the National Consumer Law Center. Raher’s article explains:

- How incarcerated consumers are denied basic aspects of customer care – such as refunds for shoddy products, meaningful warranties, or even the expectation that a product will be well made. (pp. 72-76)

- How prison retail companies attempt to justify the high prices they charge incarcerated customers. For instance, prison retailers often claim that high prices are necessary because of the overhead costs associated with security. But these overhead costs — to the extent that they are real–are likely canceled out by common business functions that prison retailers don’t have to spend money on, such as advertising and operating a network of brick-and-mortar stores. (p. 25)

- How prison retail companies have avoided regulation. For instance, some prison phone companies are attempting to brand themselves as “information services” companies, a class of company subject to fewer regulations and less oversight. (p. 52)

- How prisons and jails themselves exacerbate the problem. Not only have a growing number of correctional facilities shifted the costs of incarceration onto incarcerated people (for example, by making people pay for medical supplies or clothing), they also frequently garnish portions of family members’ deposits into their loved ones’ trust accounts, making it even more expensive for people on the outside to support their loved ones. (pp. 81-82)

- What sources of protection are available. Incarcerated people and their family members may have rights under existing laws like the Communications Act, the Electronic Fund Transfer Act, or state consumer-protection statutes. Some activist groups have scored major victories under these laws, but often legal action is impossible or impractical given ubiquitous arbitration clauses and class-action bans that appear in companies’ terms of service. (p. 33)

There are also detailed discussions of data breaches impacting incarcerated people (pp. 40-44), deceptive advertising practices (pp. 36-40), and the rapidly-expanding practice of utilizing computer tablets inside prisons and jails (pp. 21-23).

Historically, there was little need for consumer protection in correctional facilities because the facilities used to provide basic necessities and incarcerated people had little need to engage in commercial transactions. But as more essential goods and services — toothpaste, phone calls, socks, etc. — are accessible only via purchase, people are faced with commercial exploitation while they are incarcerated.

Unfortunately, incarcerated people are uniquely vulnerable because in many segments of American law (like telecommunications), government regulators have taken a hands-off approach under the belief that consumers will choose companies that don’t treat them unfairly, and therefore the market will self-police. This logic has no place in correctional facilities, where phone and commissary vendors enjoy monopoly powers, and consumers have one choice: submit to an unfair transaction, or go without toothpaste or a phone call with family.

The article concludes with eight concrete policy proposals that describe how state and local governments, and federal lawmakers, can take modest but meaningful steps to protect incarcerated people and their families from unfair and oppressive commercial transactions.

The article is long and detailed, so we prepared a table of contents for it with links to the individual sections:

Table of contents

- Background p. 5

- Surveying the Landscape of Prison Retailing p. 9

- End Users p. 9

- Payers p. 10

- Facilities p. 12

- Vendors p. 15

- Telecommunications p. 16

- Commissary p. 17

- Money Transmitters, Correctional Banking, and Release Cards p. 18

- Tablets: The New Frontier p. 21

- Unfair Industry Practices p. 23

- Masquerading as Cream: Inflated Prices and Inefficient Payment Systems p. 24

- What Law Applies? p. 30

- Terms of Service: Carrying a Bad Joke Too Far p. 33

- Advertising, Privacy, and Consumer Psychology p. 35

- Data Insecurity p. 40

- Potential Sources of Protection p. 46

- Telecommunications Law p. 46

- Technology Has Outpaced the Regulatory Framework p. 51

- The New Cross-Subsidies p. 54

- Advocacy and Activism p. 56

- Financial Services Law, Money Transmitters, and Prepaid Accounts p. 58

- Categorizing Prepayments p. 60

- Financial Services Law and Prison-Related Transfers p. 61

- Legal Issues Related to Release Cards p. 64

- UDAP Statutes p. 66

- Prices p. 68

- Terms and Conditions p. 70

- Sales of Goods p. 72

- Antitrust p. 75

- Policy Recommendations p. 76

- State and Local Governments p. 77

- Reimagine Procurement Practices p. 77

- Foster Competition p. 78

- Conduct Rulemaking Proceedings to Protect Consumers p. 80

- Provide Protection for Trust Account Balances p. 81

- Develop Independent ADR Systems p. 82

- Federal p. 83

- CFPB Regulation of Correctional Banking p. 83

- Congressional Action p. 84

- Wright Petition, Post-Remand p. 85

- Conclusion p. 86

The Bureau of Justice Statistics is tasked with collecting, analyzing, and publishing data about the criminal justice system. But its reports are slowing down - and its framing of criminal justice issues is becoming more punitive.

by Wendy Sawyer,

November 14, 2019

We’ve heard this question from a few advocates and journalists who, like us, depend on the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) and other government data sources for timely information about the justice system. And while monitoring changes in federal data collections isn’t a core part of our work, we have observed a troubling trend: Since 2017, data releases are slowing down.

We aren’t the only ones who have noticed. Last month, a coalition representing thousands of academic and nonprofit researchers and advocates wrote to the Office of Justice Programs with questions about missing and delayed data releases as well.

I probably don’t have to convince our regular readers that timely data is essential for identifying both social problems and effective policy solutions — and that it’s especially important in the context of criminal justice, where the human costs are so high. And admittedly, it’s not news that government justice data has long been less well-funded, less timely, and less comprehensive than, say, labor statistics.

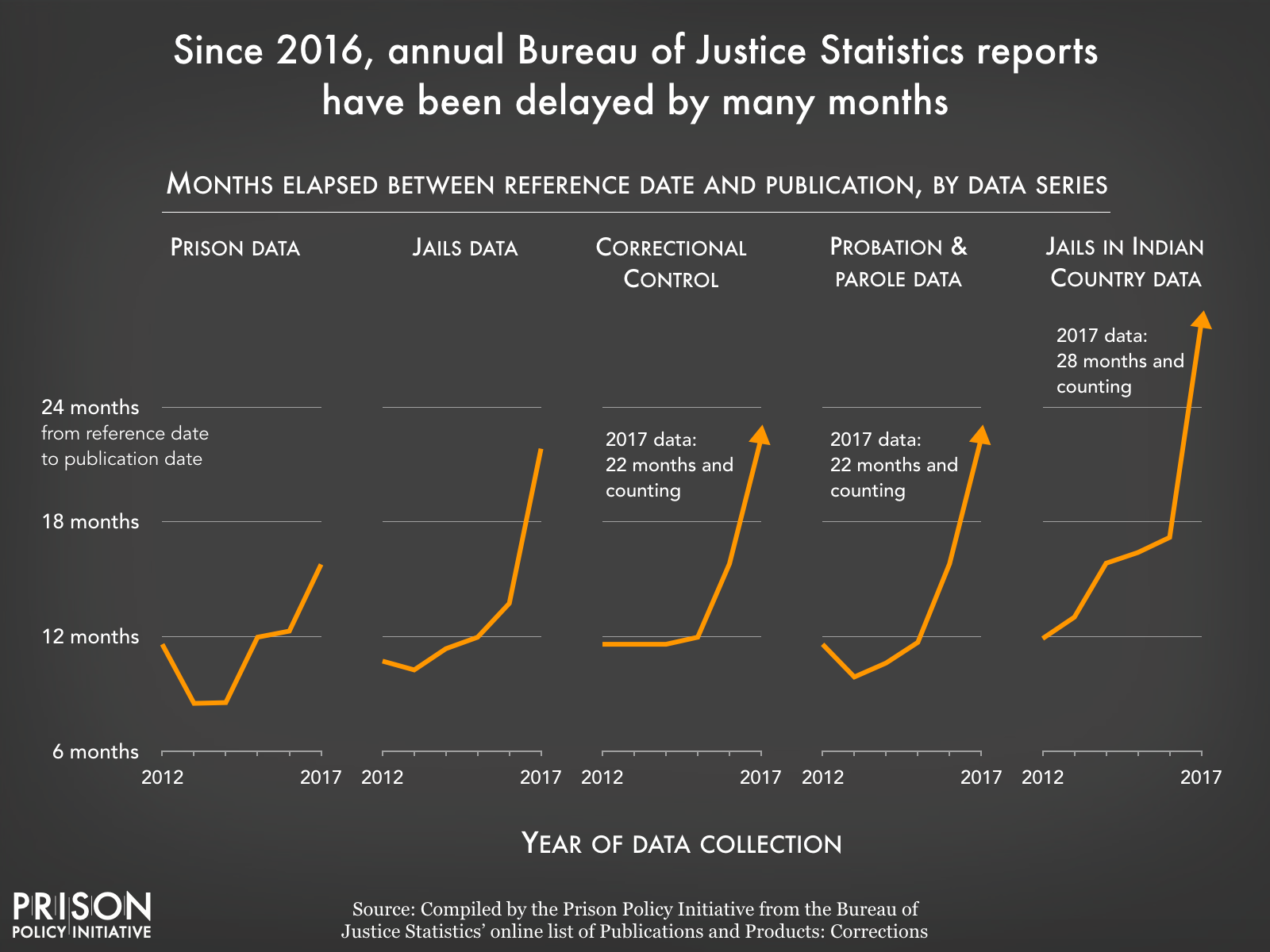

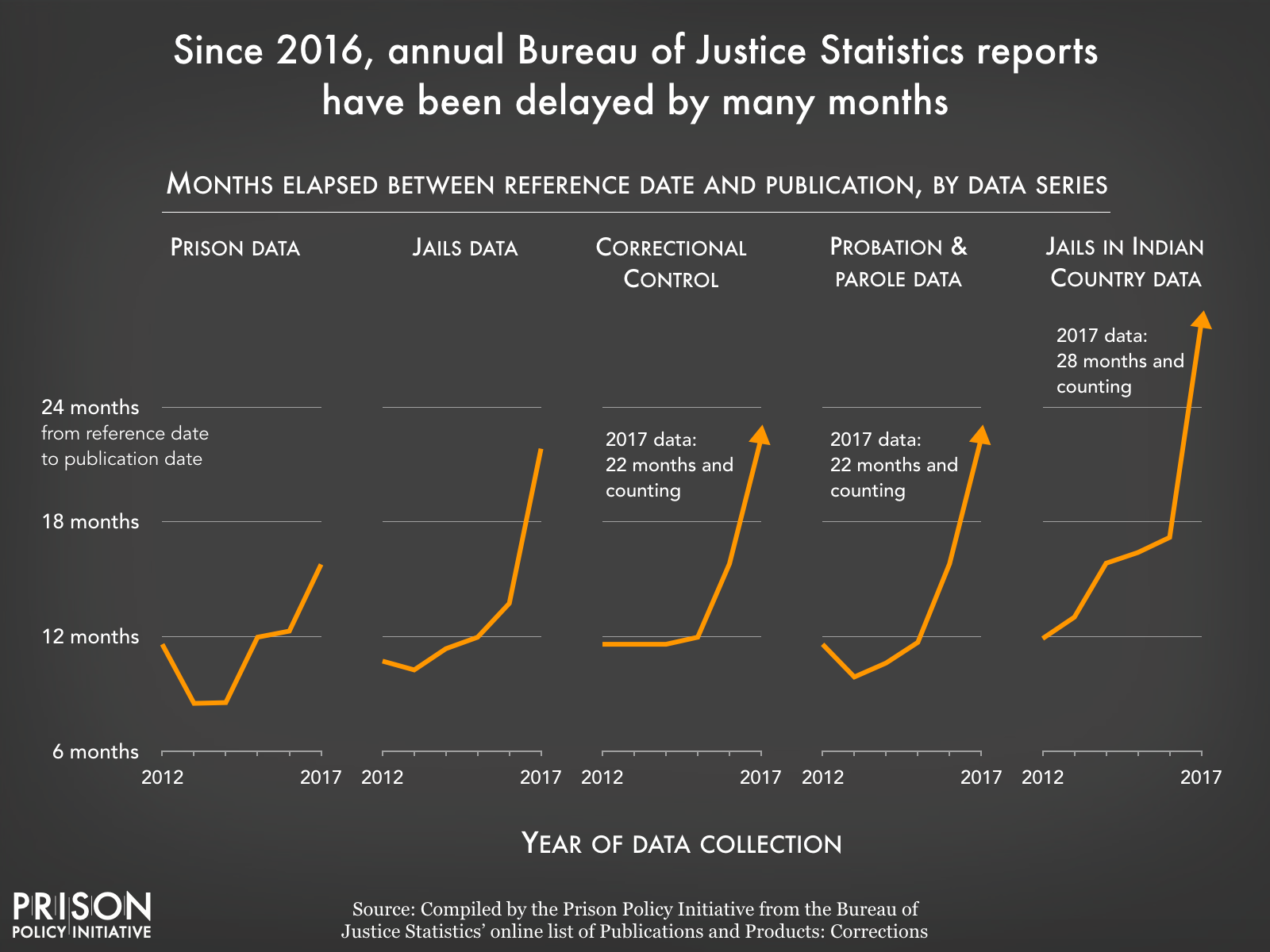

Even so, these publications have slowed even further — and even been curtailed — under the current administration. To see the extent of this trend, I went through the BJS’ list of publications since 2000 and compared the time between the data collection reference dates and the corresponding report publication dates for six annual report series. I found that there has indeed been a dramatic change in the past several years:

The time between data collection and data publication for most regular Bureau of Justice Statistics reports has increased dramatically in the last few years.

The time between data collection and data publication for most regular Bureau of Justice Statistics reports has increased dramatically in the last few years.

Publication delays in annual Bureau of Justice Statistics reports

I looked at six report series that have been on annual schedules for years: Jail Inmates, Prisoners, Probation and Parole in the United States, Correctional Populations in the United States, Jails in Indian Country, and the Mortality series (formerly Deaths in Custody). These are the reports that we rely on to produce our Whole Pie and Correctional Control reports, and provide data for many of our other briefings and publications.

I found that while data collection activities for these series have continued, BJS data releases and reports have all experienced significant delays, starting in 2017:

- The annual Prisoners report provides a “snapshot” of who’s incarcerated in state and federal prisons on a given day, allowing the public and policymakers to spot trends and respond to them as quickly as possible. These reports came out like clockwork for years, typically within 7-12 months of the year-end data collection. The 2017 prison data was 4 months later than usual, released in April 2019. We have not yet seen 2018 data from BJS, but the Vera Institute of Justice released state prison data it collected independently earlier this year, essentially “lapping” the government’s data collection and publication.

- Since 1996, the Jail Inmates report, which offers a similar “snapshot” of local jail populations across the U.S., has been published within one year of the data collection reference date (usually June 30). The 2017 report was released 22 months after the midyear reference date, and it’s already been over 16 months for the 2018 data. The delay on this report is especially concerning, given how quickly jail populations can shift with changes in policing, prosecution, or court processes.

- The Probation and Parole report serves a similar trend-monitoring purpose, but focuses on the 4.5 million people on probation and parole in the U.S. These reports were reliably released in late fall of each year after data collection, dating back to 2004. (In the 10 years before that, these reports came out even sooner, by late August.) The 2016 report, however, was released in April 2018, and we’ve now been waiting over 22 months for the 2017 data.

- The Correctional Populations reports present data on people who are incarcerated and those under community supervision, and sometimes include useful data on these populations before the more targeted prison or jail reports are published. These reports were published consistently in late fall of the year following data collection until December 2016, when 2015 data were reported. The 2016 report was late, and we have yet to see the 2017 data, which now reflect the correctional populations of over 22 months ago.

- The very narrow glimpse we have into how the justice system operates on tribal lands largely comes from the Jails in Indian Country reports. Typically released within 12-18 months of the June 30 data reference date, it’s now been almost 2 years since the last time BJS released a report in this series, although the 2017 and 2018 data have been collected.

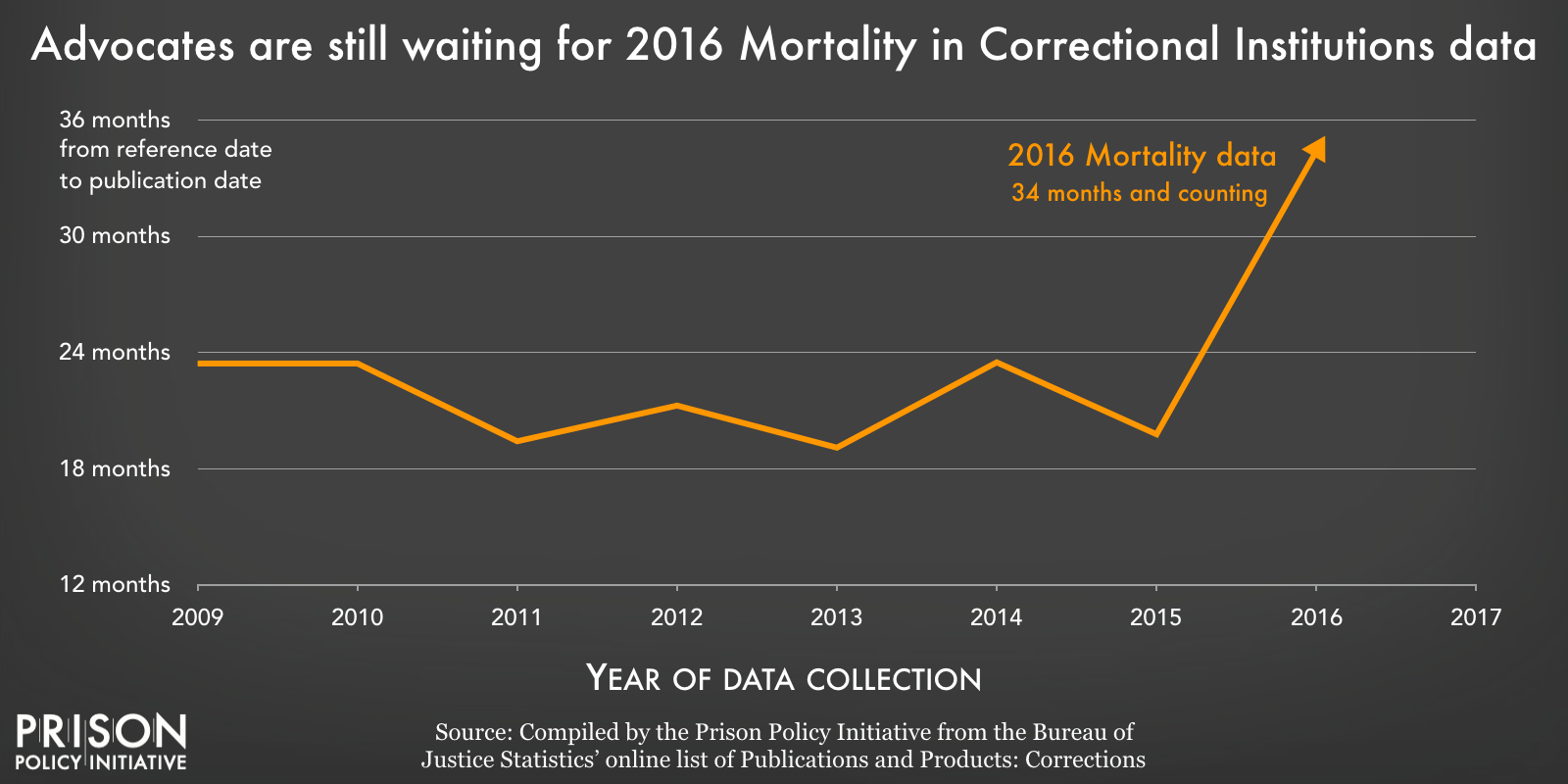

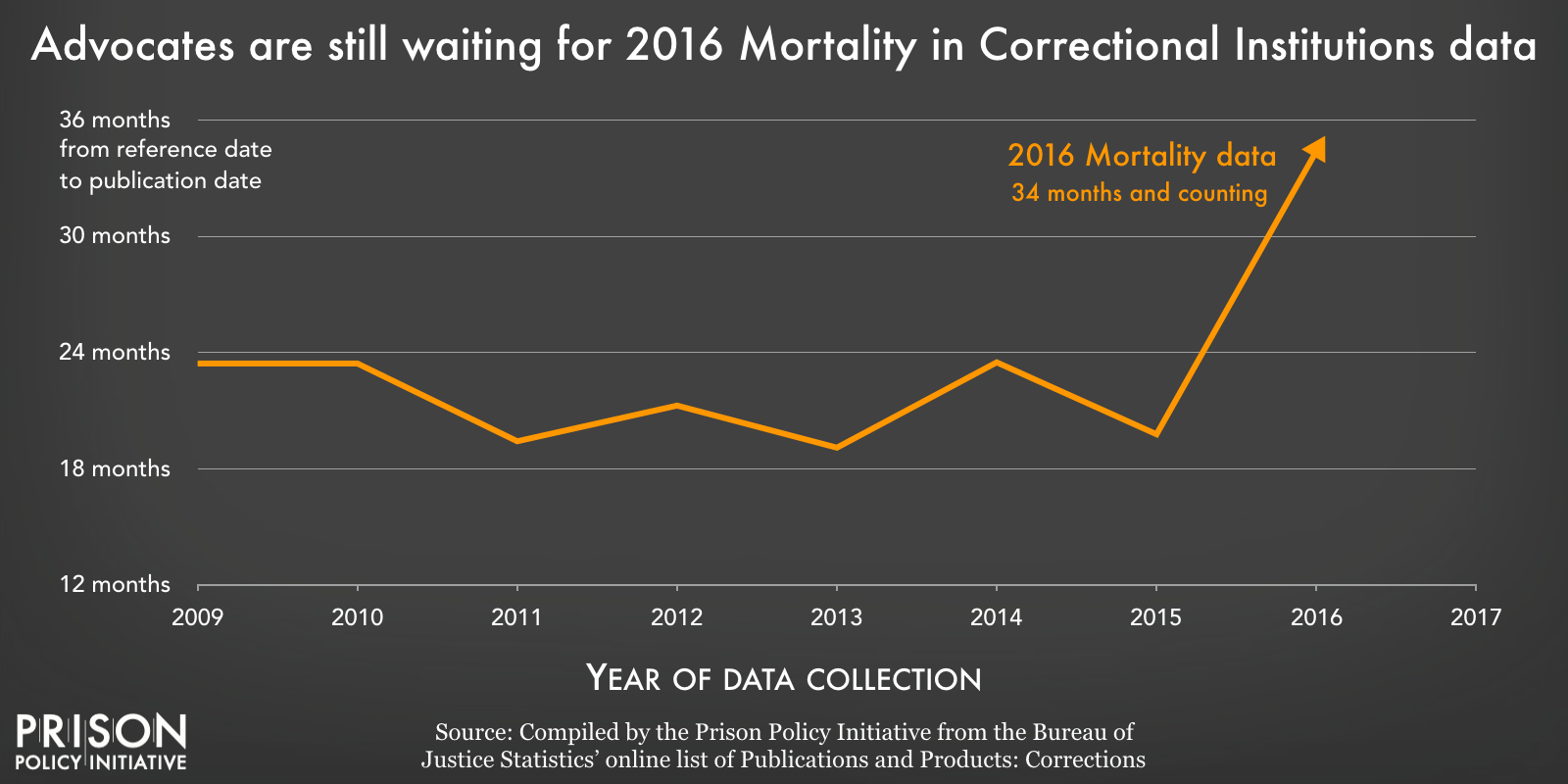

- Finally, the Mortality reports are our only “official” source of information about deaths in prison and jail custody; they are essential for holding correctional agencies accountable for preventable deaths from suicide and homicide. They also help shine a light on the life-threatening health problems among incarcerated people. Yet the last two Mortality reports only gave us part of the picture, reporting only deaths in prisons in 2014 and only HIV-related deaths in prisons in 2015. And although these reports are published on a slightly slower schedule (18-24 months from the data reference date), these, too, have been badly delayed. The most recent data on jail deaths available is from 2013 — despite increasing attention to jail suicides and a law requiring this data to be reported annually — and three years of data have been collected since we last saw any reports.

Researchers and advocates are concerned about other delays at BJS

In October, as I mentioned above, a coalition headed by the Crime and Justice Research Alliance and COSSA wrote to the Office of Justice Programs with questions about other missing and overdue BJS publications.

Of special concern is the 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates (SPI). The SPI was conducted every 5-7 years from 1974-2004, and was finally conducted again in 2016. In the intervening years, we saw the high-water mark of mass incarceration thus far, and witnessed tremendous growth and change in correctional control. Yet BJS has published none of the invaluable data contained in this survey, which includes “demographic characteristics, current offense and sentence, incident characteristics, firearm possession and sources, criminal history, socioeconomic characteristics, family background, drug and alcohol use and treatment, mental and physical health and treatment, and facility programs and rule violations, etc.” Almost none of the 2016 data has been released, three years later and counting. Only a report on the methodology and a report on a subset of the data on firearms have been released to date.

The coalition’s letter also highlights delays in the annual Background Checks for Firearms Transfers reports (the last data reported are from 2015), and asks whether a planned survey of police forensic units, commissioned by the Department of Justice in 2014, has been abandoned.

It gets worse: Important data on jails and pretrial detention won’t even be collected for years

The Bureau of Justice Statistics is also many years behind schedule for at least one crucial and long-awaited data collection, the Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (SILJ). The SILJ was collected every 5-7 years from 1972-2002, and it provides the most comprehensive, nationally representative data available on people held in local jails. It’s especially important for the information it offers about the pretrial (or unconvicted) population. Unbelievably, the 2002 SILJ is the most recent source we have to measure what portion of people held pretrial are there because they can’t afford a bail bond, what racial disparities exist among pretrial detainees, and what offenses people are locked up for before trial. After much delay, the current plan has the next survey slated for 2021; assuming it is released in 2022, it will be 15 years off-schedule.

Another data series that sheds light on pretrial decisions, State Court Processing Statistics, was “halted in 2009 due to concerns about cost and representativeness,” according to a recent BJS-funded study by the Urban Institute. According to that report, BJS “plans to implement a new data collection series to develop national statistics on the processing of pretrial defendants…This program, National Pretrial Reporting Program (NPRP), was conceptualized to supplement or replace the State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS) program.” While the feasibility study tested an experimental survey and recommended an alternative sampling method that would make the sample nationally representative, it’s been 10 years now since BJS has released any new data on pretrial processes.

Beyond delays: “Trimmed” data from the FBI, politicized language at OJJDP and BJS

Government justice agencies have not merely delayed their data releases: They’ve also made partisan decisions that undermine the transparency and impartiality we expect from them. These issues extend beyond the Bureau of Justice Statistics to other reporting agencies.

In 2017, the FBI “strategically trimmed the amount of tables” from 81 to 29 in the agency’s annual report on arrest data and trends, Crime in the United States. The missing data included information as fundamental as arrests by sex. In response to “user feedback” — and very likely, assertions that it reflected the Trump administration’s “suppression of government data and…unwillingness to share information” — 70 “supplemental” tables were later released.

Advocates have also noticed troubling changes on the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention’s website, changes “that indicate a shift toward a more punitive approach to juvenile justice under the Trump administration.” For example, a webpage with the OJJDP’s policy guidance on “Eliminating Solitary Confinement for Youth” was taken down, and the new administration also issued a “language guidance” document directing OJJDP employers and contractors to replace widely-accepted terms with decidedly less pointed terms that downplay systemic problems. The document suggested changing references to “justice-involved youth” with the more stigmatizing “offender” label, “underserved youth” with “all youth,” and avoid referring to juvenile delinquency or crime as a “public health issue” and always emphasize “public safety.”

This signaling of the new administration’s priorities wasn’t just performative; the new OJJDP administrator Caren Harp also attempted to undermine efforts to reduce racial disparities among justice-involved youth by “slashing the kinds of data that local agencies must collect.” Harp reasoned that there hadn’t been enough progress to justify the data collection — leaving advocates wondering how collecting less data would improve matters.

In a previous briefing, I’ve already highlighted some alarmist framing in a recent BJS press release; other analysts and advocates have noted these “heavily politicized” communications as well. While the BJS reports themselves remain valuable data sources and politically neutral in tone, the headlines of the accompanying press releases in the past year or so have become increasingly alarmist and reflective of the Trump administration’s rhetoric. (Of course, this is not the first administration to politicize press releases: many will remember that former BJS Director Lawrence Greenfeld was replaced in 2005 because he objected to the Bush administration’s attempts to suppress findings of racial disparities in a BJS press release.)

So what’s going on?

The reasons behind these decisions and delays are unclear — is it funding problems? Staff shortages? Changes in leadership? It could well be any, or all, of these problems.

BJS has been “flat funded” for years, despite the massive growth in the number and size of the correctional agencies they survey, and despite increasing demands for justice system data under laws mandating annual data collection, like the Prison Rape Elimination Act and the Deaths in Custody Reporting Act. A National Academies publication explains that this has been a problem under both Democratic and Republican administrations, going back decades.

The Crime and Justice Research Alliance and COSSA — the coalition that wrote the October letter to the DOJ I mentioned earlier — suggest that staffing problems may explain the delays. They write, “[M]any in the criminal justice research community have heard of an alarming decline in the number of BJS staff as a consequence of hiring freezes, staff attrition, and failure to replace departing staff and experts.” Again, this is an agency that has been chronically underfunded and understaffed relative to the herculean task of collecting and analyzing the nation’s decentralized justice system data.

And then there is the issue of leadership. With its mandate to produce reliable, large-scale studies with national, state, and local policy implications, effective leadership at BJS requires “strong scientific skills, experience with federal statistical agencies, familiarity with BJS and its products, [and] visibility in the nation’s statistical community,” among other qualities. That’s according to four former BJS Directors and the President of the American Statistical Association, who wrote to former Attorney General Sessions in 2017 to encourage the appointment of an experienced research director to head up BJS.

That didn’t happen. Instead, since late 2017, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has been under the leadership of Jeffrey Anderson, whose only prior statistical experience appears to be the co-creation of a college football computer ranking system in 1992. On criminal justice, all I could find in his history were a handful of 2015-2016 articles in which he argues against criminal justice reform. In a National Review article, he called Obama-era Washington “tone-deaf on crime,” despite the widespread bipartisan support of criminal justice reform. Sadly, the problems we’re seeing with data delays and politicized language suggest that the current leadership may not agree about the importance of the agency they lead.

Welcome Jenny Landon, our new Development & Communications Associate!

by Wendy Sawyer,

November 1, 2019

Please welcome our new Development & Communications Associate, Jenny Landon.

Please welcome our new Development & Communications Associate, Jenny Landon.

Jenny is a 2016 University of Massachusetts graduate, with a degree in Social Thought and Political Economy. She previously worked on anti-corruption campaigns as an organizer with Represent.Us. Most recently, she honed her development and communications skills at Tapestry, a local community health organization. We’re excited to grow our team’s capacity to take on more projects with Jenny’s help.

Welcome, Jenny!

The time between data collection and data publication for most regular Bureau of Justice Statistics reports has increased dramatically in the last few years.

The time between data collection and data publication for most regular Bureau of Justice Statistics reports has increased dramatically in the last few years.

Please welcome our new Development & Communications Associate, Jenny Landon.

Please welcome our new Development & Communications Associate, Jenny Landon.