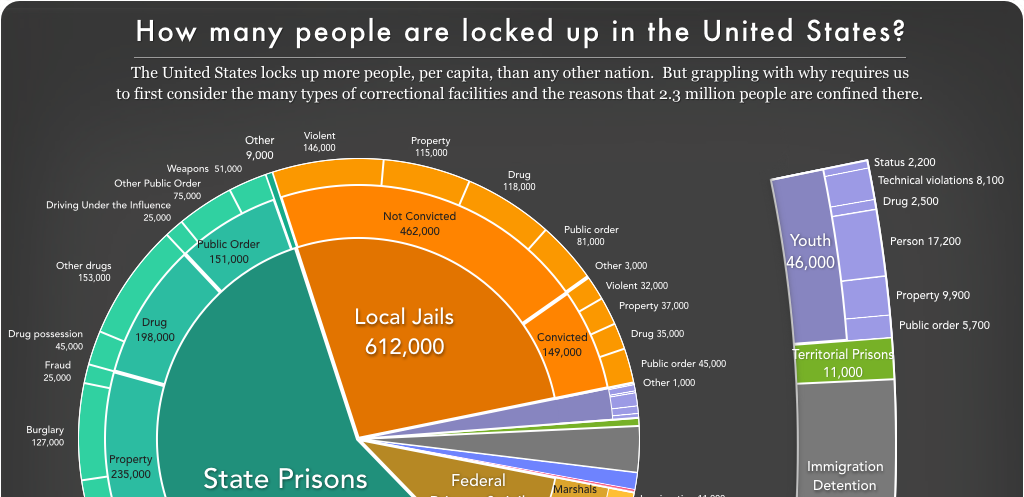

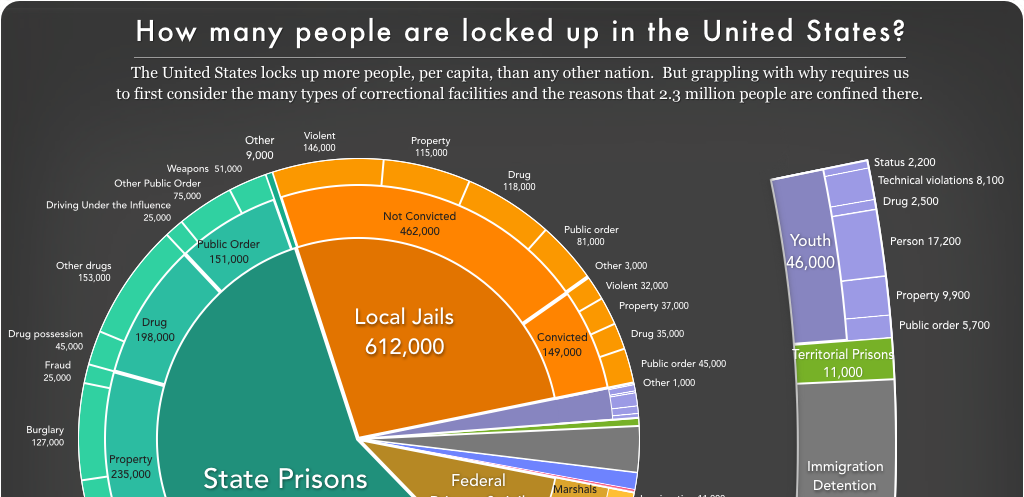

With this year's updated edition of Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, we once again answer the essential questions of how many people are locked up, where, and why.

March 19, 2019

Easthampton, Mass. – Are there 1.3 million people incarcerated in the U.S., or is it actually closer to 2.3 million? Why – and where – are these millions of Americans behind bars? The country’s fragmented systems of confinement make answering basic questions about mass incarceration unnecessarily difficult. With this year’s updated edition of Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, we answer these essential questions with the most recent data, highlighting causes of incarceration that get too little attention as well as incarceration “myths” that receive too much.

The publication of the new report caps a year-long effort to update the public on the major drivers of incarceration – state prisons and local jails – as well as confined populations too often overlooked, such as people in post-release “civil commitment centers” and undocumented immigrants in detention.

“With such high public support for criminal justice reform, it’s urgent that we have a clear picture of who is locked up and where,” said author Wendy Sawyer. “For instance, many people don’t realize how much of mass incarceration is local. But one in four incarcerated people – and one in four ICE detainees – are held in local jails controlled by county sheriffs.”

The report’s other key findings include:

- 76% of people in local jails are not convicted of a crime, and many are there simply because they can’t afford money bail.

- 49,000 people are held by ICE for immigration offenses – a 43% increase since 2016. (This does not include the 11,800 immigrant children currently detained by the Office of Refugee Resettlement.)

- In a single year, 168,000 people were incarcerated for nothing more than a “technical violation” of probation or parole, such as a failed drug test.

- Contrary to a popular myth, only 7% of incarcerated people are held in privately-run facilities – but virtually all incarcerated people generate profit for private companies by paying for phone calls, medical care or other necessities.

The United States locks up more people than any other country, at a rate more than five times higher than most other nations. One impediment to reform is the lack of available data to guide that conversation. In Whole Pie, the Prison Policy Initiative provides the comprehensive view of mass incarceration that society needs in order to plot a path forward.

Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie is one in a series of reports that provide equally comprehensive snapshots of women’s incarceration and youth confinement. Previous national reports from the Prison Policy Initiative include Following the Money of Mass Incarceration, which uses economic data to show who pays for and who benefits from mass incarceration, and Correctional Control, which breaks down the number of people in every state who are incarcerated, on probation, or on parole.

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization leads the nation’s fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (via prison gerrymandering) and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone industry and the video calling industry.

The full report and graphics are available at https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2019.html

Tablet computers are delivering a captive audience to profit-seeking companies, while enabling prisons to cut essential services like law libraries. We investigate.

by Mack Finkel and Wanda Bertram,

March 7, 2019

We released an updated briefing on prison tablets in 2024. We recommend reading that, instead.

This article was updated in May 2021 with details about California’s prison tablet contract, and in August 2023 with information about additional attempts to eliminate existing services in favor of tablets in prisons.

Twelve states have recently signed contracts with prison telecom companies to provide tablet computers to incarcerated people – a sharp increase since we began analyzing these contracts in 2017. Though many prisons already allow incarcerated people to buy tablets, these contracts provide something different: Tablets for free, ostensibly at no cost to either consumers or taxpayers. (To be clear, these aren’t like the iPads you can buy at a store; they’re cheaply made, with no internet access.)

But as with most state contracts that appear to cost nothing, there is a catch – several, in fact.

First, the “free” tablets charge users at every opportunity, including above-market prices for phone calls, video chats and media. Even sending an email requires a paid “stamp.” Furthermore, our recent analysis of these contracts suggests that they actually put the interests of incarcerated people last, prioritizing cost savings and the provider’s bottom line.

For instance, many of these contracts:

- Guarantee the Department of Corrections a portion of tablet revenue.

- Allow tablet providers to alter the prices of services – such as email, music and money transfer – without state approval.

- Allow providers to terminate tablet services if the tablets aren’t profitable enough.

- Exempt providers from replacing a broken tablet if they think it was “willfully” damaged – a loophole ripe for exploitation, as prison tablets are cheaply made and break easily.

More details below:

Table 1. Findings from our analysis of eight “no-cost” contracts between state Departments of Corrections and tablet providers. Contracts are listed from oldest to newest. For more on GTL and Securus (JPay), the predominant tablet providers, see our recent report State of Phone Justice. In this table, “Active since” denotes the date that installation of tablet equipment in the correctional facility began.

**Note: While news reports state that each person in Vermont prisons is receiving a tablet, Vermont’s contract with GTL (which originally provided for kiosks, with the option for the state to request tablets) is less clear. According to the contract, tablets will be provided to up to 90% of people in each “living unit” in Vermont prisons. (See page 36 of the contract.)

| Contract |

Active since |

Does the DOC receive a portion of tablet revenue? |

Can the provider cancel the service for reasons related to profitability? |

Are the terms of use subject to DOC approval? |

Will the provider replace broken tablets? |

Example of service charges on tablets |

| Colorado DOC and GTL |

August 2015 (suspended in 2018) |

Yes. DOC earns a flat payment of $800,000 per year. |

Yes. GTL can cancel the service if there is insufficient tablet revenue, or if more than 10 tablets in any one housing unit need to be repaired. |

No, DOC does not have to approve the Terms and Conditions. |

GTL has discretion to determine whether damage was “willful,” and does not have to replace willfully damaged tablets. GTL also does not have to replace more than 5 (or 5%, whatever is greater) tablets in a housing unit every year. |

A digital music subscription costs $19.99 per month. |

| Missouri DOC and JPay |

March 2017 |

Yes, DOC earns a 20% commission on songs, albums, movies, ebooks, and games. |

Yes. JPay can cancel the service if there is insufficient revenue. |

No. Terms of use not mentioned in contract (and therefore likely not subject to DOC oversight.) |

Unclear. |

A subscription to NewsStand, an app that allows one to read the news, costs $5.95 per month. |

| Vermont DOC and GTL** |

April 2017 |

Yes. The contract specfies that the DOC receives 32% of commissary sales, but it is unclear what percent of tablet media sales are paid to the DOC. |

Unclear. The contract does not specify revenue metrics as cause for termination. |

Tablet usage tracking/monitoring is required in the contract, and the state determines what limited number of functions are provided, but the contract does not specify terms of use. |

Unspecified. The contract indicates that GTL will provide the state with their company repair procedure policy. |

1 week of streaming music: $7.99; 30 day access to game center: $5.99 |

| New York DOCCS and JPay |

August 2017 |

No. |

No, contract does not specify circumstances in which service can be canceled. |

No. Terms of use not mentioned in contract (and therefore likely not subject to DOC oversight.) |

Unclear. |

Sending an email requires paid “stamps” starting at $0.35 (emails can require several stamps, depending on length). |

| South Dakota DOC and GTL |

March 2018 |

Yes. DOC earns a 50% commission on electronic messages and 24.2% on most types of phone calls. |

Yes. GTL can cancel the service if there is insufficient revenue or if equipment is “subjected to recurring vandalism.” |

No, DOC does not have to approve the Terms and Conditions. |

GTL has discretion to determine whether damage was “willful,” and does not have to replace willfully damaged tablets.

|

A 14-day digital music subscription costs $14.99, including a $9 “infrastructure charge.” |

| Indiana DOC and GTL |

July 2018 |

Yes, DOC earns a 10% commission on purchased content (not including phone or video calls made on tablets). |

Yes. GTL can cancel service in housing units where 10 or 10% of tablets are damaged in a year. |

Yes, DOC must approve the Terms and Conditions. |

GTL has discretion to determine whether damage was “willful,” and does not have to replace willfully damaged tablets.

GTL does not have to replace tablets more than once for any given incarcerated person, nor does it have to replace more than 5 or 5% of tablets in a housing unit every year.

|

A 30-day subscription to “unlimited podcasts” costs $9.99. |

| Delaware DOC and GTL (pilot program) |

October 2018 |

No. |

Yes. GTL can cancel the service if too many tablets are damaged. |

Yes, DOC must approve Terms and Conditions. |

Unclear.

|

Reading e-books, sending messages, or accessing music, movies, or games costs $0.05 per minute. |

| Maine DOC and Edovo |

December 2018 |

No. |

No, contract does not specify circumstances in which service can be canceled. |

Yes, DOC must approve Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy. |

The facility has discretion to determine whether they or Edovo will replace damaged tablets. Edovo does not have to replace more than 5% of tablets for free every year. |

Sending more than 10 electronic messages per month costs between $10 and $50, depending on the number of messages one wishes to send. |

| South Carolina DOC and GTL |

January 2019 |

No. |

No, contract does not specify circumstances in which service can be canceled. |

No. Terms of use not mentioned in contract (and therefore likely not subject to DOC oversight). |

GTL is required to repair or replace damaged tablets or equipment, regardless of the cause of damage or loss. |

Sending electronic messages costs $0.25 per message. |

| Connecticut DOC and JPay |

April 2019 |

Yes, commissions to the DOC include 10%-35% revenue for replacement technology, purchases of external hardware accessories, and fees for emails, songs/music, news subscriptions, etc; and 50% of printing fees. |

No, contract does not specify circumstances in which service can be canceled. |

Yes, user agreement (including privacy and ownership provisions) is specified in contract, but unclear whether terms must be approved by DOC. |

Jpay will “repair and/or replace any broken or damaged Tablets and Kiosks as directed and authorized by the Department.” Any tablet that is “intentionally damaged or destroyed” must be replaced at cost to the DOC. Unclear who decides if a tablet was intentionally damaged. |

Audiobooks are available for $0.99-19.99 each. News subscriptions are $4.99 a month. Each email is $0.30. |

| West Virginia DCR and GTL |

October 2019 |

Yes, the WVDCR receives a 5% commission on all gross revenue. |

Yes. GTL can cancel the service if there is insufficient revenue. |

No. Terms of use not mentioned in contract (and therefore likely not subject to DOC oversight). |

Unclear, but contract states that GTL “will in no way be responsible, or liable for…the safety, efficacy, or use of the tablets…Tablets are provided ‘as is’ without warranty of any kind.” |

Reading e-books, sending messages, or accessing music, movies, or games costs $0.05 per minute. |

| California DCR and GTL |

December 2020 |

Yes. DOC earns a flat payment of $200,000 per year, which it says is “to cover the State contract management responsibilities and services.” |

Unclear. |

No mention of Terms and Conditions. |

“The state shall provide reasonable measures against loss by pilferage or destruction. The vendor shall be responsible for any expenses required for the repair of the equipment.” |

A video call costs $0.20 per minute, or $6 for a 30-minute call. |

Providers and DOC officials often describe free tablets as a gift to incarcerated people, but they more closely resemble a corporate investment than a gift. For the companies, free tablets with expensive services more than pay for themselves down the line. And for prison administrators, tablets pave the way for the elimination of essential services. We’ve already seen prisons eliminate:

- Law libraries. South Dakota eliminated its paralegals and physical law library after rolling out tablets. A subsequent lawsuit alleged that the tablet software meant to replace the law library is often unusable, and deprives incarcerated people of meaningful access to the courts.

- Physical books. In 2018, Pennsylvania ended book donations to incarcerated people in favor of costly e-books, many of which were lifted directly from the free online library at Project Gutenberg (this policy was ultimately repealed and replaced with a cumbersome policy requiring book donations go through a “secure processing center” before being delivered to incarcerated people). New York and Maryland also tried to end book donations (before public pressure forced them to backtrack), and one large Florida jail even took away Bibles, replacing them with low-quality e-Bibles on tablets. In Cook County, Illinois, the sheriff’s office declared “paper products” contraband in 2023 and has limited access to books, offering tablets as an “alternative.”

- Postal mail, which prisons can eliminate in favor of digital mail scans (as Pennsylvania did) and paid electronic messaging.

- Music and Mp3 players. In 2017, the Florida Department of Corrections transitioned from MP3 players to tablets and people who had bought hundreds or thousands of dollars of music lost access to the music on the MP3 players, as they were confiscated as contraband when replaced with tablets.

- Educational programming. Tablets are increasingly being used to supplement – and supplant – in-person higher education in prisons, leading to a “subpar educational experience” and significant technical difficulties in many state prisons, including in Missouri and Florida. In Massachusetts in 2022, the Department of Corrections chose to not reapply for more than $2 million in state educational grants for prison programs, and instead encouraged using tablets (which the state has already spent $14 million on) that are “pre-loaded with educational materials that they can use to study on their own” (the DOC maintains that this is in an effort to “offer more enrichment,” rather than replace existing teachers and programs).

All this being said, there is nothing inherently wrong with tablet technology, in or out of a prison setting. It’s certainly possible to imagine using tablet technology to substantially improve prison life — if states can ever learn to distinguish truly innovative policies from high-tech ploys to cut costs.

The movement for phone justice has won huge victories in state-run prisons, but people in jail pretrial are on the front lines of exploitation.

February 11, 2019

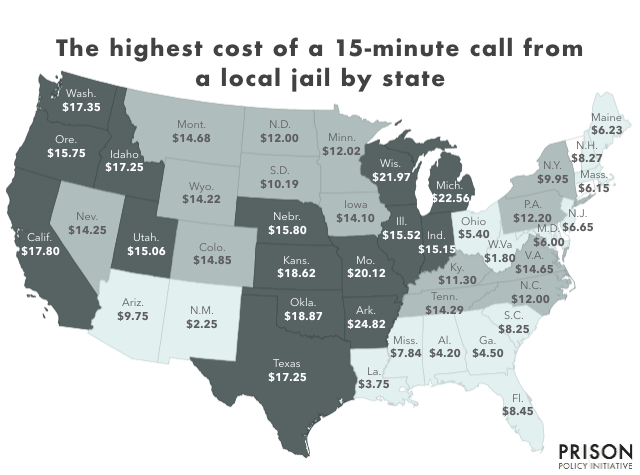

County and city jails frequently charge incarcerated people $1/minute or more for a phone call, far more than even the worst rates in state prisons, a new 50-state report finds. The Prison Policy Initiative report State of Phone Justice uncovers the cost of phone calls in over 2,000 jails nationwide, explaining why sheriffs sign lucrative phone contracts that prey on pretrial detainees.

“Jails have managed to escape the political pressure that forced many prisons to bring their rates down,” said co-author Peter Wagner. “We found that many jails are charging three, five or even 50 times as much as their state’s prisons would charge for the same phone call.” The report explains how:

- Phone providers compete for jail contracts by offering sheriffs large portions of the revenue – and then charge exorbitant phone rates.

- Providers exploit sheriffs’ lack of experience with telecommunications contracts to slip in hidden fees that fleece consumers.

- State legislators, regulators and governors pay little attention to jails, even as they continue to lower the cost of calls home from state prisons.

“High phone rates impact everyone in jail, but those worst affected are people detained pretrial because they cannot afford bail,” co-author Alexi Jones said. “When someone has to organize their defense from jail, the cost of phone calls becomes extremely limiting, and that ultimately makes our justice system less fair.”

The report also includes:

- A sortable table of the cost of phone calls in jails nationwide, as well as the provider each jail contracts with;

- A table comparing the cost of prison phone calls in each state to the cost of jail phone calls;

- Explanations of two specific profit-making tricks used by jail phone providers, which target the very poorest consumers at their moments of crisis (with explanatory comics by illustrator Kevin Pyle);

- A timeline showing how the two largest phone providers, Securus and GTL, are locking facilities into perpetual contracts by buying up their competitors.

“If we’re going to tame the correctional phone market, we need sheriffs, state legislators, public utilities commissions and federal regulators to understand the significance of jail phone calls,” Wagner said.

Phone providers are so creative in their influence-peddling that the most viable reform strategies do not focus only on "commissions."

by Peter Wagner and Alexi Jones,

February 11, 2019

The prison and jail phone industry is rife with problems – from sky-high phone rates to inexplicable consumer fees to expensive and unnecessary “premium services” – and all of these problems can be traced to a single moment in the industry’s history: When the companies decided to start offering facilities a percentage of their revenue in order to win contracts.

Before long, jails and prisons were prioritizing commissions over low rates when choosing a phone provider. This didn’t just saddle incarcerated people and their families with higher phone rates – it created two major problems for the companies, both of which have caused the market to spiral into dysfunction.

Problem 1: The arms race for higher commissions

Prison phone companies started offering commissions to jails and prisons in order to win contracts from companies that didn’t offer them. What they didn’t expect was that sheriffs would become dependent on this new income. The companies were forced into an “arms race,” competing to give away more and more of their revenue from phone calls; the proffered commissions inched ever closer to 100%.

The companies had painted themselves into a corner: How do you make a profit when you’ve given virtually all of your revenue away? Their solution: Find another source of revenue and hide it from the facility’s management.

That’s why, today, prison and jail phone companies have learned to sustain themselves with revenue entirely separate from phone rates. The first of these hidden sources of revenue is consumer fees – fees to deposit money, open accounts, or get a refund.

The second source of revenue is a suite of unrelated, profitable services that the companies bundle into phone contracts, such as money transfer, commissary sales, video calls, emails, etc. Most recently, the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision signed a contract for over 50,000 “free” tablet computers, alongside its phone contract with Securus. (The tablets are, of course, not “free” for incarcerated people and their families, who pay to use the tablets and are generating millions in profit for Securus.)

Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

Smart Communications promises the impossible. (What could go wrong?) Source: Screenshot from http://www.smartcommunications.us

The most extreme – and telling – example so far of the prison phone market’s reliance on extra services comes from a provider named Smart Communications. This year, the Florida-based company began marketing to facilities on a promise of “100% phone commissions.” The catch should be obvious: The provider makes money by bundling other profitable services into the contract, and sharing none of this additional revenue with the facilities.

Such extravagant promises reveal what providers have been doing all along: promising higher and higher commissions by relying more and more heavily on ancillary services and fees to boost profits.

Problem 2: Circumventing new regulations

Gradually, the public has come to understand that there is an inherent conflict of interest when facilities award monopoly contracts and then reap a percentage of the revenue. As a result, the commission system started to fall out of favor. Some – though far from all – state legislatures started to prohibit percentage-based commissions.

But legislatures left open a critical loophole: They didn’t prohibit companies from offering all improper perks to facilities – only commissions.

Instead of paying a fixed percentage of their revenue to the facilities, the companies now use the extra revenue to issue kickbacks in other forms. From the perspective of the poor families paying for the calls, nothing has changed – phone rates remain high – but for the companies, disguising payments in this way makes it harder for journalists and advocates to track the kickbacks. These payments include:

As such, some of the prison and jail systems that have been widely hailed for refusing phone commissions do not, in our opinion, deserve the praise:

- In 2007, the County Commissioners of Dane County, Wisconsin voted to ban the commissions that brought in nearly $1 million per year. The County Supervisor explained, “We’ve lost our moral compass and direction for a million bucks a year.” But in 2009 the county negotiated a new contract where instead of taking a commission, it would just take an “administrative fee” of $476,000 in monthly increments.

- By statute, the California prison system does not take a percentage commission, but it’s quite happy to take cash and cell phone blocking equipment, which was expected to cost GTL between $16.5 million and $33 million to install. (It should also come as no surprise that states with lower phone rates have fewer problems with contraband cell phones and therefore have no need for jamming equipment.)

- Since 2008, the Michigan Department of Corrections has refused percentage commissions. However, in 2011, they raised their rates1 and started requiring that their provider pay money into a “Special Equipment Fund.” As of 2018, this fund takes in $11 million per year, which would amount to a 57% commission. As a result — despite lowering their phone rates in 2018 — Michigan’s phone calls are more expensive calls than 23 states that take traditional commissions.2

Not all hope is lost, of course. Sheriffs and legislatures still have the power to clean up this mess and make the prison and jail phone industry fair for consumers. But to do so, they’ll have to start evaluating phone contracts differently, focusing on more than just percentage commissions. Sheriffs and legislators should also ask whether:

- Consumers are getting a good price for phone calls and ancillary fees.

- The phone contract prohibits the provider from steering calls to more expensive methods.

- The contract does not include other correctional services. (Bundling phone contracts with other things the facility needs makes it impossible for the facility and the families to determine whether the cost for each service is reasonable.)

- The contract does not include “free” products like tablets which are paid for through the sale of “premium” content.

- The contract specifically lists all rates, fees and charges. (It is unfortunately common for facilities to sign contracts without knowing what the provider is going to charge for ancillary fees, or for products that the providers label as “premium” or “convenience”.

Similarly, it can be really tempting to want to ban percentage commissions. We instead suggest two different ways to change the incentives behind these contracts:

- Require contracts to be negotiated on the basis of the lowest price to the consumer. (New York law does this for the state’s prison phone contract.)

- Cap commissions not as a percentage but as a fixed number of cents per minute, say 1 cent a minute. This approach maintains the problematic system of families subsidizing the correctional system, but is in improvement in that it gives the facilities an economic incentive to increase call volume and to monitor their provider for unnecessary fees and services that cut in to call revenue.

Suggested reading for more on the topics here:

- See Prison phone provider accuses Florida Dept. of Corrections of using inmates’ families as a slush fund by Ben Conarck of the Florida Times-Union about how Florida “explicitly prohibited” contract bids that offered a percent commission, and then during negotiations demanded (and received from the winning bidder) a “wish list of goodies” instead of lower rates.

- Our August 1, 2013 letter arguing that the Federal Communications Commission should take an expensive view of “commissions.”” This letter was written when we still thought it practical to prohibit all commissions, but the detail in our letter reviews many of the most egregious examples of commissions packaged under other names.

- Our August 12, 2015 letter to the Federal Communications Commission with our investigation of the industry’s campaign contributions. We make the case that the FCC should focus on lowering the total cost of calls instead of chasing the infinite forms that commissions are taking.

- Our article about the prison phone industry’s new business model: “fee harvesting.” In this 2015 article, we explain why the providers focus on fees and why the facilities have a a real but short-sighted incentive to look the other way.

The cost of jail phone calls punishes people in the most desperate circumstances, most of whom have not been convicted of a crime.

by Wendy Sawyer,

February 5, 2019

It’s easy to see how people in state prison, who spend years or decades behind bars, are hurt by the cost of phone calls. But less obvious is how people in jail, who are usually behind bars for much shorter periods, can be hit even harder by the same cost.

The answer has to do with why people are in local jails in the first place. In many cases, it’s solely because they are poor. On a given day, 3 out of 4 people held in jails under local authority have not even been convicted, much less sentenced. Very often, they simply cannot afford the bail amount set by the court as a condition of release. (Men in jails reported earning a median of $17,676 per year before incarceration (in 2018 dollars). For women, the median pre-incarceration income was just $11,184 per year, well below the poverty line.)

When people can’t get together the funds to get out of jail, exorbitant phone rates only make a difficult time even harder. Pretrial detention is an extremely stressful experience; detainees are often at risk of losing their jobs, housing, and even custody of their children. Being locked up, even for a short time, can interrupt medical care and can exacerbate mental health problems. It’s no coincidence that suicide risk is highest in the first week of jail incarceration. Calls with loved ones are essential for people under these conditions, who may need to coordinate childcare or elder care, make arrangements for missing work, have prescriptions brought to the facility, or simply have someone to talk to while incarcerated. Expensive phone calls further punish people in jails – most of whom, again, have not been convicted of a crime.

Even beyond the potential damage to one’s health and personal affairs, pretrial detention also negatively affects case outcomes, and it’s in this way that high phone rates from jails do the most harm to the justice process itself. People who can’t afford money bail are forced to organize their defense from jail, where it is much harder to contact people who can help – and the cost of calling them from jail is even more limiting. In a 2016 opinion in a case about the proper use of phone calls in pretrial processes, Judge Jenny Rivera acknowledged the difficulty of preparing a defense while detained:

“Pretrial detention hampers a defendant’s preparation of his defense by limiting ‘his ability to gather evidence [and] contact witnesses’ during the most critical period of the proceedings…The detained suspect…lacks a similar ability [to a defendant free on bail or their own recognizance] to contact witnesses and gather evidence.”

People detained pretrial are more likely to plead guilty just to get out of jail, more likely to be convicted, and more likely to get longer sentences. Costly phone calls play a central role in this injustice by limiting how often and how long pretrial detainees can talk to their families and friends in the service of their defense. This makes it harder for defense attorneys to coordinate with family to build mitigation cases or track down witnesses. As a result, pretrial detainees often present a weaker defense than they would have if they had been able to make calls freely (or better, had not been detained in the first place).

Furthermore, on a systemic level, high phone rates from jails hurt indigent defendants by draining already-scarce resources from public defenders’ offices. As the Missouri State Public Defenders explained in a letter to the FCC, these offices pick up the tab for phone calls from clients in jail, which can add up to tens of thousands of dollars every year. In the long term, they say the cost “reduces our ability to communicate with our clients about their cases, diminishes the quality of representation we are able to provide, and thus risks denying clients their Sixth Amendment right to effective counsel.”

So jail phone companies (and jails themselves, which get kickbacks on these calls) are essentially subsidized by public defenders – and by extension, taxpayers – while public defenders are left with even fewer resources to help indigent clients. Ultimately, this, too, makes conviction more likely.

But, wait, you might ask, if you’ve been paying attention to this issue: Didn’t the government solve this problem years ago? Didn’t the FCC limit how expensive phone calls from correctional facilities could be?

Partly, yes: In 2014, the FCC set limits on rates for out-of-state calls from prisons and jails. But here too, unfortunately, people in jails get shortchanged. People in jails almost always make in-state calls, meaning that the FCC’s rate caps don’t apply to 92% of calls from jail. Instead of paying 21 cents or less per minute, as they would for out-of-state calls, people in jail calling loved ones in-state often still pay $1 per minute or more.

The cost of these calls continues to get less attention from regulators, journalists and the public than it deserves. There’s an irony in that: When poor people in jail can’t afford to make phone calls, the fairness of the justice system is distorted – and everyone pays an outsized price.

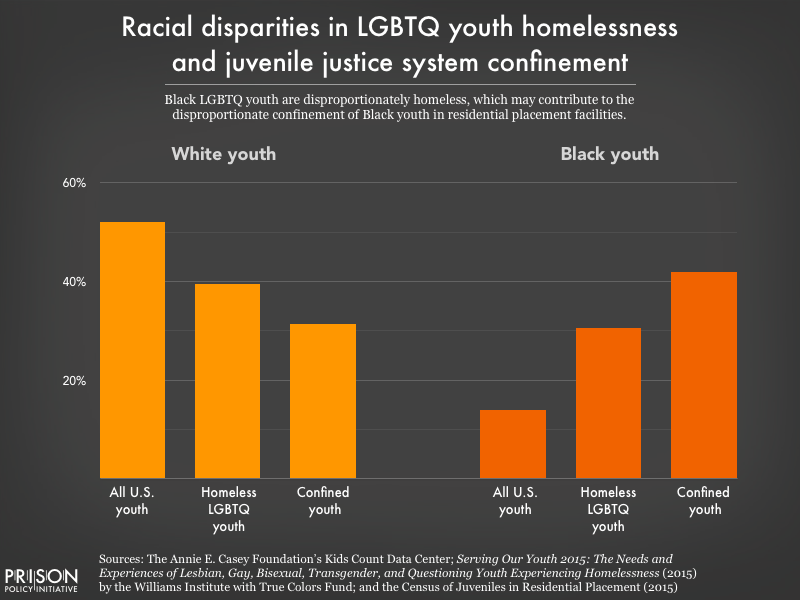

Homelessness is the greatest predictor of involvement with the juvenile justice system. And since LGBTQ youth compose 40% of the homeless youth population, they are at an increased risk of incarceration.

by Daiana Griffith,

January 22, 2019

In a recent report, we found a strong link between incarceration and homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. But while we examined racial and age disparities among that population, we weren’t able to address how homelessness affects justice-involved youth — especially LGBTQ youth who are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. In this piece, we highlight research that elucidates the relationship between homelessness and LGBTQ youth incarceration, while also emphasizing how homelessness and incarceration disproportionately affect LGBTQ youth of color.

LGBTQ youth face higher rates of detention and incarceration. A 2015 study shows that 20% of all youth in the juvenile justice system identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming, or transgender, even though they compose only 5 to 7% of the total U.S. youth population. (Troublingly, the portion that identify as LGBTQ and/or gender nonconforming is even higher for girls in the juvenile justice system, at 40%.) This high percentage of justice-involved LGBTQ youth may be driven by their even higher rates of homelessness.

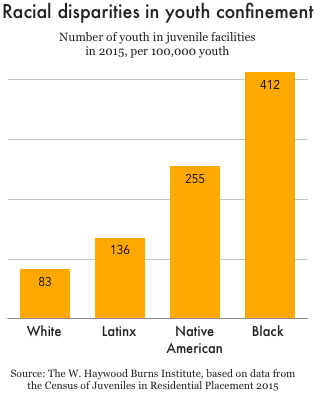

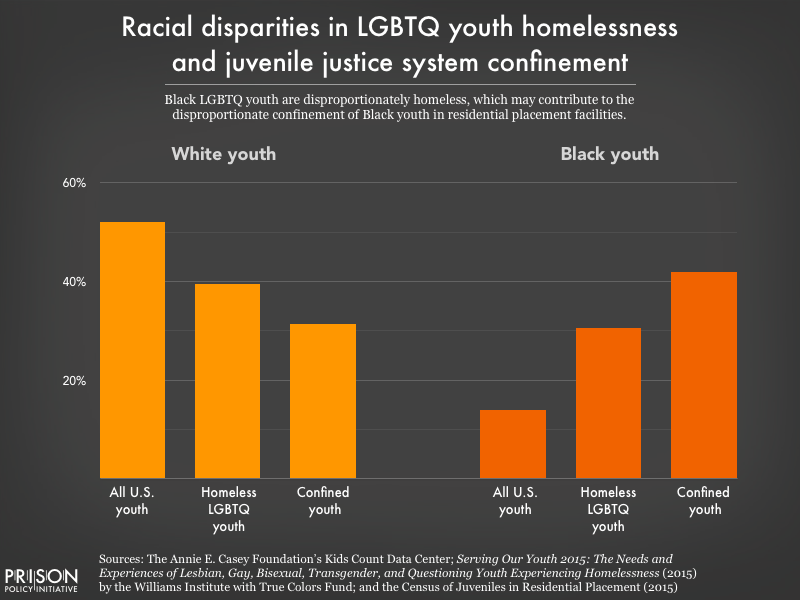

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

According to a Center for American Progress report, homelessness is the greatest predictor of involvement with the juvenile justice system, and 40% of homeless youth identify as LGBT. LGBTQ youth usually face homelessness after fleeing abuse and lack of acceptance at home because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Once homeless and with few resources at hand, LGBTQ youth are pushed towards criminalized behaviors such as drug sales, theft, or survival sex, which increase their risk of arrest and detainment.

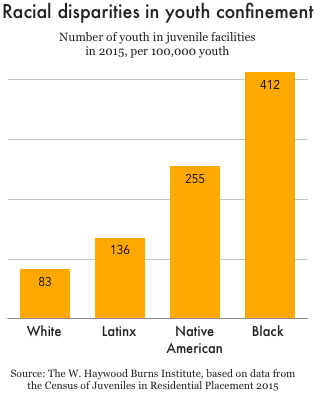

LGBTQ youth of color — particularly Black youth — are at an increased risk of criminalization. This, in part, reflects the fact that LGBTQ youth of color have disproportionately high rates of homelessness. A 2014 survey of human service providers serving homeless youth, for instance, reported that 31% of the LGBTQ youth they served identified as African-American or Black, despite Black youth making up only 14% of the general youth population in 2014. The racial disparities in youth homelessness contribute to the overrepresentation of youth of color in juvenile facilities in general; in 2015, 2 out of 3 youth in juvenile facilities were either Black, Hispanic, or American Indian.

The disparities in youth incarceration mean that LGBTQ youth, and especially youth of color, also face the harms related to incarceration at greater rates. Incarceration, for example, can be detrimental to young people’s physical and mental health, their relationships, and their social and economic prospects. Among these different consequences, access to stable housing can be especially negatively affected.

Youth in the juvenile justice system are likely to end up with juvenile delinquency records that can prevent them from accessing housing and finding employment once released. Similar to formerly incarcerated adults, justice-involved youth are subjected to discrimination by public housing authorities and private property owners, which, combined with affordable housing shortages, exposes them to housing insecurity.

In the case of justice-involved LGBTQ youth, housing discrimination based on criminal records can be compounded by housing discrimination against LGBTQ people. A 2017 study based in the D.C. metropolitan area found that housing providers were less likely to book an appointment with gay men, as well as less likely to tell homeseekers who disclosed their transgender identity about available units.

These alarming statistics remind us that LGBTQ youth are at a higher risk of both homelessness and incarceration, and the many harms accompanying these situations. This means that if we are to put less youth behind bars, we must address the specific needs of LGBTQ youth who often end up homeless because of family conflict. In addition, we have to make finding stable housing post-release and eradicating discrimination based on criminal records a priority to avoid cycles of reincarceration.

Daiana Griffith is a student at Mount Holyoke College, graduating in May 2019. She contributed this post as a student volunteer over the winter term.

While preparing a report grading every state's parole release system, Jorge Renaud takes a deep dive into what makes a parole system fair and just.

by Jorge Renaud,

January 2, 2019

When someone from the Northeast hears I’m on parole for a robbery in Texas, they invariably say something like, “Boy, I bet you’re glad you live in Massachusetts now,” assuming that the parole system in Massachusetts is as progressive as the state’s political reputation. As we prepare a report grading the parole release systems of all 50 states, the time is right to address this question — and dispel some myths.

From 30,000 feet the criminal justice landscapes of Texas and Massachusetts look very much as we expect from such typically red and blue states. Texas actively puts people to death; Massachusetts abolished the death penalty in 1982. You can’t vote in Texas if you have a felony conviction and are either incarcerated or on any type of supervision. In the Commonwealth, the only people denied the right to vote are in prison with felony convictions, but once they are out they can vote whether or not they are on parole or probation. And when it comes to sheer numbers, Massachusetts has the lowest incarceration rate in the country, with 324 individuals behind bars for every 100,000 residents, compared to the Texas rate of 891, the 7th highest among all states.

However, when it comes to parole, I’ve found that states that look progressive may in fact be oppressive, and those we dismiss as backwards might in fact face forward.

Prisons are the most visible, obvious manifestation of criminal justice. And for those incarcerated in prisons, the experience is shaped by hope: that they will someday leave prison, join civil society and never return. The likelihood that this hope will be realized in a given state — that an incarcerated person will be released and not return to prison — can largely be quantified. Measurable outcomes of state policies affect their chances: the frequency with which people are given life sentences, the average time incarcerated individuals actually serve, how often parole is granted, and how often paroled individuals are sent back to prison for minor, non-criminal violations rather than supported as they move back into society. Together, these factors make up what I’ll call a state’s “hope index” for people serving long sentences.

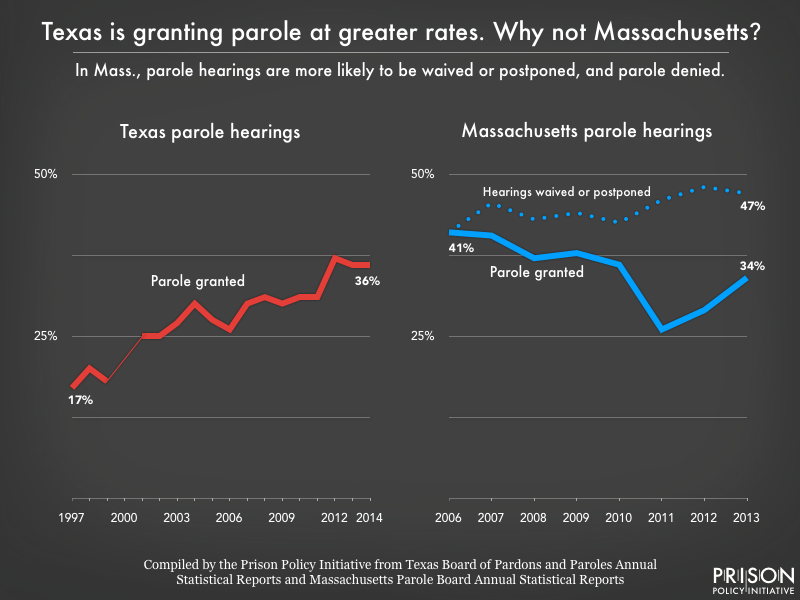

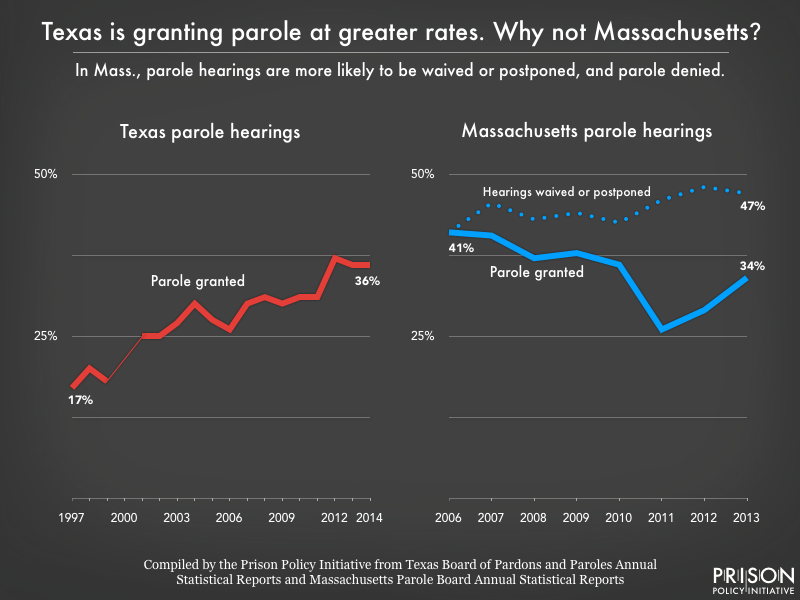

Let’s look at the factors that comprise the “hope index” of Texas and Massachusetts. Two of those measures are fairly even — how long individuals stay in prison and how readily they are released on parole. In 2015, Bureau of Justice Statistics data showed that 15 percent of individuals in Texas prisons had been there over 10 years. For Massachusetts, that number was 19 percent. The Robina Institute reported that in 2014, 36 percent of all parole hearings in Texas resulted in release being granted. Robina’s latest data for Massachusetts is for 2013, when the Commonwealth paroled 34 percent of all individuals eligible for release who actually attended hearings. (That same year, the Massachusetts Parole Board reported that the “paroling rate” was 58 percent. However, that number doesn’t take into account the 2,944 waivers by incarcerated individuals who “may not be interested in adhering to expected parole conditions….” More on that in a moment.)

Figure 1. In Texas, the parole grant rate more than doubled between 1997 and 2014 (no data were available for 2000). In Massachusetts, the grant rate fell between 2006 and 2013, while the portion of hearings that were waived or postponed increased, to make up nearly half of all scheduled release hearing outcomes in 2013. (For an explanation of this data, and why our calculated grant rates for Massachusetts are lower than those reported by the state, see the data note at the bottom of this post.)

Figure 1. In Texas, the parole grant rate more than doubled between 1997 and 2014 (no data were available for 2000). In Massachusetts, the grant rate fell between 2006 and 2013, while the portion of hearings that were waived or postponed increased, to make up nearly half of all scheduled release hearing outcomes in 2013. (For an explanation of this data, and why our calculated grant rates for Massachusetts are lower than those reported by the state, see the data note at the bottom of this post.)

The gap in the “hope index” becomes wider when we look at those who have an expectation of release. The Sentencing Project argues that sentences of over 50 years are “virtual life” sentences and adds those to the count of individuals sentenced to either life or life without parole (LWOP). By that count, one of every four people in a Massachusetts prison in 2016 was serving a life or virtual life sentence — the 6th highest rate in the country. Texas ranked 28th in that dismal category, with 12 percent of all individuals in Texas prisons serving life or virtual life sentences. (Lest the Commonwealth believe that including “virtual” life sentences is unfair, using just LWOP sentences leaves Massachusetts with the 2nd highest rate; 12 percent of everyone in Massachusetts prisons have LWOP sentences, trailing only Louisiana’s 13 percent. In Texas, that number is 0.5 percent.)

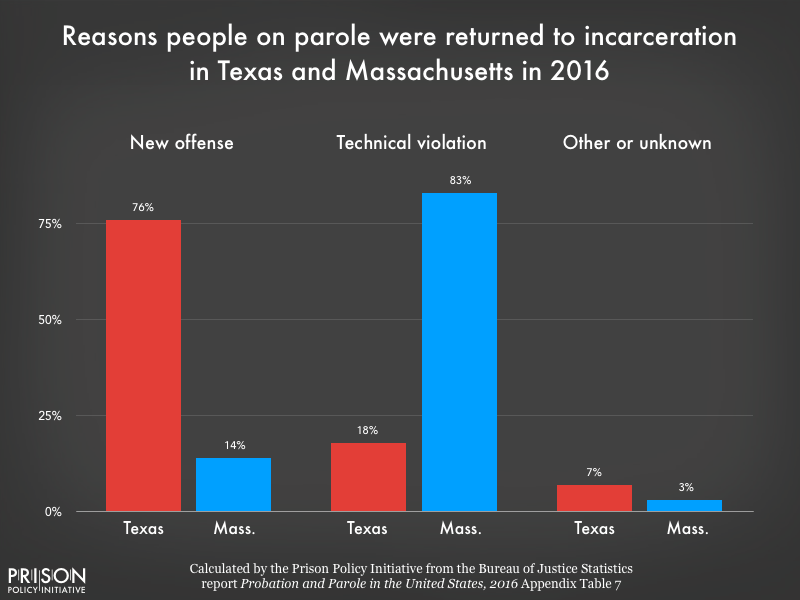

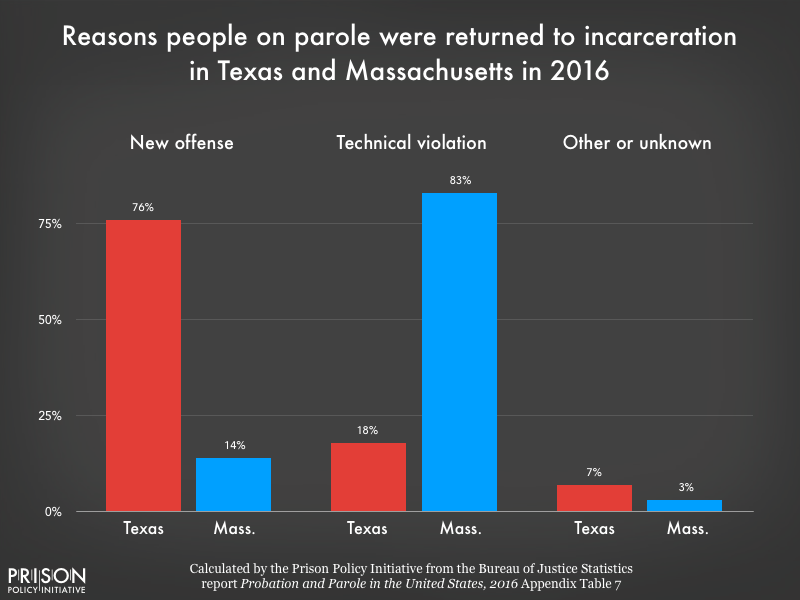

When it comes to staying out after release on parole, the two states again look very different from what we might expect. In 2016, Massachusetts returned 490 individuals on parole to prison; 83 percent of those were returned for a technical violation (that is, without committing a new offense). Texas returned 7,142 to its prisons, of which 18 percent were for technical violations without a new offense. Put a different way, in 2016 Massachusetts returned almost a quarter (22 percent) of its entire parole population to prison without any of them committing a new offense, while Texas returned just one percent for technical violations. In Texas, parole offers a real hope of success for those released. In Massachusetts; well, as state officials themselves write, “By virtue of being under supervision in the community, an inmate may have a higher likelihood of re-incarceration.”

Figure 2. While Texas has a much larger parole population overall, and therefore returned more people to incarceration in 2016, three-quarters of returns to incarceration in Texas were for new offenses. Meanwhile, technical violations accounted for more than 4 out of 5 returns to incarceration from parole in Massachusetts.

Figure 2. While Texas has a much larger parole population overall, and therefore returned more people to incarceration in 2016, three-quarters of returns to incarceration in Texas were for new offenses. Meanwhile, technical violations accounted for more than 4 out of 5 returns to incarceration from parole in Massachusetts.

Why does Massachusetts have such a low “hope index,” especially compared to Texas? Maybe the Commonwealth is diverting individuals with low-level offenses and only sending individuals to prison who commit serious and violent crimes. However, in both states, violent offenses account for approximately two-thirds of the prison population (60 percent in Texas compared to 70 percent in Massachusetts).

It may be that the Massachusetts “hope index” is skewed because over half of all scheduled parole release hearings are postponed or waived. By far the largest percentage of individuals leaving prison in the Commonwealth discharge their sentence, or “max out.” This means that a large number of individuals in Massachusetts prefer to finish their sentence rather than be on parole. (Which begs the question: Why?)

The truth, however, is simpler. First, despite the “throw away the key” rhetoric of the state’s politicians, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles has doubled its parole grant rate from 18 percent in 1999 to 36 percent in 2014, which was a big part of why the overall incarceration rate in Texas dropped from 1,050 in 2003 to 837 in 2014.

Second, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles doesn’t revoke many individuals on parole, especially not for technical violations without a new offense. The agency has not returned more than 3 percent of its parole population to prison for a technical violation since at least 2006, when the Bureau of Justice Statistics began compiling that data.

But most critically, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles only votes on releases and revocations — its staff do not supervise individuals on parole. That is done by the Parole Division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. This means parole officers in Texas are free from the political pressure that Massachusetts parole officers and supervisors surely feel, because in the Commonwealth, the officers out in the field are directly accountable to the political appointees who grant parole.

If you think that isn’t important, consider that then-Governor Deval Patrick cleaned out the entire Massachusetts Parole Board in 2011 for voting to release — and improperly supervising — Domenic Cinelli, who killed a Woburn police officer while on parole. Contrast that to the reaction of Texas parole officials when recently paroled Jose Gilberto Rodriguez killed three people and shot two others in July of 2017, sending Houston into a panic. Texas politicians didn’t hurl charges at the Board of Pardons and Paroles or its members, and an agency official told me they didn’t take those events lightly, but that those things “happen” and they did not plan any changes, in either supervision or release policies.

A final crucial difference between Texas and Massachusetts parole policies has a less quantifiable outcome, but surely affects individual success at rejoining civil society: In Texas, unlike Massachusetts, people under parole supervision are able to connect with other formerly incarcerated people, even if all are on parole, and draw on each other as a source of support. There are groups of individuals on parole and probation in Texas who are active politically, and whose voices and experiences are respected at meetings of city councils, commissioners’ courts, and at the Capitol. Massachusetts, in contrast, has a general parole condition that specifically prohibits anyone on parole from engaging “in a continuous pattern of association with persons known to have a criminal record…” and, in no uncertain terms, warns those on parole that they must, at the risk of revocation, tell their parole officer any time they are going to be in the presence of someone who has a criminal record. For those on parole, this policy not only isolates them from those who might best support and advise them as they move back into their communities — it gives any individual on parole the subtle message that they, too, are viewed with suspicion, and that others are warned against associating with them.

It’s impossible to explain the fact that Massachusetts — progressive, blue-state Massachusetts — returned to incarceration in 2016 almost a fourth of all individuals being supervised by the state parole board without those individuals being convicted of a new crime. So I won’t try.

What I can say is that “red” and “blue” don’t tell the entire story. Texas should take a hint from Massachusetts when it comes to slowing down incarceration rates, and Massachusetts could learn a thing or two from Texas about how to keep politics out of parole and give people serving long sentences a real reason to hope.

A note about the data

Those familiar with Massachusetts Parole Board statistics may wonder why the parole grant rates presented in Figure 1 are much lower than those reported by the Parole Board in their Annual Statistical Reports. This is because the Commonwealth excludes from its calculation all scheduled release hearings that are waived or postponed, and therefore do not result in a vote. In other states, this might not make much of a difference. But because so many hearings are waived or postponed in Massachusetts by those eligible for parole, ignoring those outcomes dramatically inflates the grant rate. Using reports from 2006 to 2013, we were able to recalculate the grant rates to include the waived and postponed release hearings. However, since 2014, the Parole Board annual reports no longer state how many release hearings were waived or postponed (instead, these hearings are lumped together with other kinds of hearings). It is therefore impossible to calculate a comparable grant rate for Massachusetts after 2013.

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

Figure 1. In Texas, the parole grant rate more than doubled between 1997 and 2014 (no data were available for 2000). In Massachusetts, the grant rate fell between 2006 and 2013, while the portion of hearings that were waived or postponed increased, to make up nearly half of all scheduled release hearing outcomes in 2013. (For an explanation of this data, and why our calculated grant rates for Massachusetts are lower than those reported by the state, see the data note at the bottom of this post.)

Figure 1. In Texas, the parole grant rate more than doubled between 1997 and 2014 (no data were available for 2000). In Massachusetts, the grant rate fell between 2006 and 2013, while the portion of hearings that were waived or postponed increased, to make up nearly half of all scheduled release hearing outcomes in 2013. (For an explanation of this data, and why our calculated grant rates for Massachusetts are lower than those reported by the state, see the data note at the bottom of this post.) Figure 2. While Texas has a much larger parole population overall, and therefore returned more people to incarceration in 2016, three-quarters of returns to incarceration in Texas were for new offenses. Meanwhile, technical violations accounted for more than 4 out of 5 returns to incarceration from parole in Massachusetts.

Figure 2. While Texas has a much larger parole population overall, and therefore returned more people to incarceration in 2016, three-quarters of returns to incarceration in Texas were for new offenses. Meanwhile, technical violations accounted for more than 4 out of 5 returns to incarceration from parole in Massachusetts.