New BJS report reveals staggering number of preventable deaths in local jails

In 2016, over 1,000 people died in local jails - many the tragic result of healthcare and jail systems that fail to address serious health problems among the jail population, and of the trauma of incarceration itself.

by Alexi Jones, February 13, 2020

A newer article about jail deaths with data from 2018 is now available. We suggest using that article instead of this one.

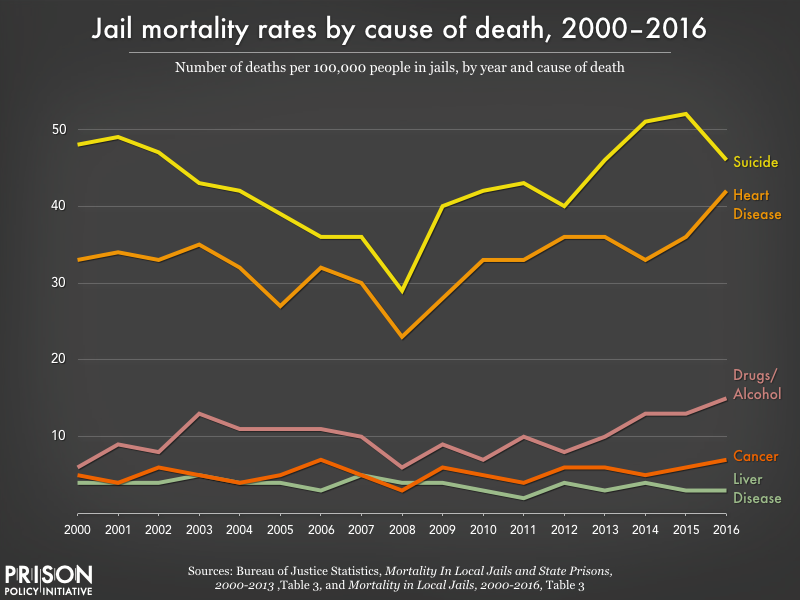

A new Bureau of Justice Statistics report reveals that over 1,000 people died in local jails in 2016, underscoring the dangers of jail incarceration. Most troublingly, the report finds at least half of these deaths are preventable, with suicide remaining the leading cause of death. These preventable deaths are the tragic result of healthcare and jail systems that fail to address serious health problems among the jail population – both inside and out of the jail setting – and of the trauma of incarceration itself.

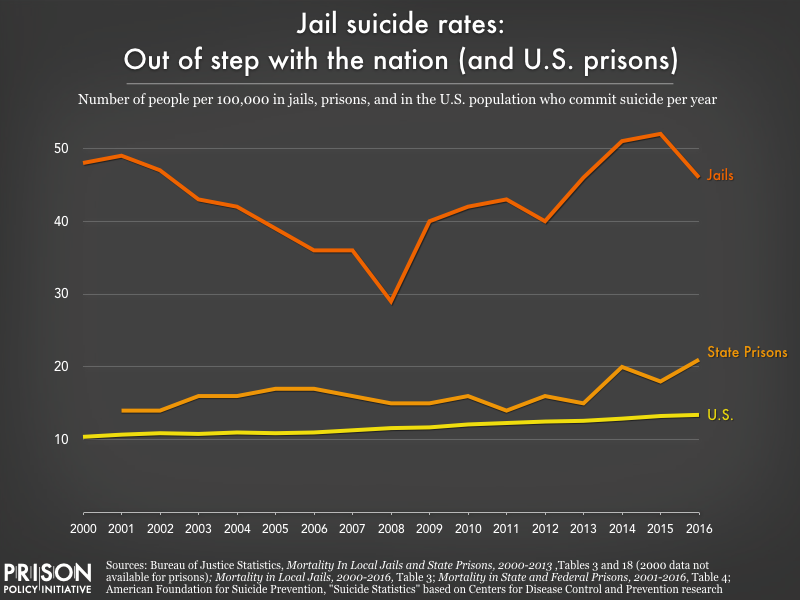

The new report reveals that half of all deaths in jails are due to suicide, accident, homicide, and drug or alcohol intoxication, all of which are largely preventable. Once again, suicide was the leading cause of death in jails. The jail suicide rate is far higher than that of state prisons or among the American population in general.

The other half of deaths in jails are due to illness, such as heart disease or liver disease, many of which likely could have be prevented if not for the abysmal healthcare in jails.

People in jail often have serious physical and mental health needs. They are five times more likely than the general population to have a serious mental illness, and two-thirds have a substance use disorder. They also are more likely to have had chronic health conditions and infectious diseases. Moreover, many people experience serious medical and mental health crises after they are booked into jail, including withdrawal, psychological distress, and the “shock of confinement.”

Yet despite their serious needs, people in jail rarely have access to adequate healthcare. History has shown that jails are unable to provide effective mental health and medical care to incarcerated people.

For example, CNN recently published a scathing investigation into WellPath (formerly Correct Care Solutions), one of the country’s largest jail healthcare providers. The investigation found that WellPath provides substandard healthcare that has led to more than 70 preventable deaths in local jails between 2014 and 2018. WellPath, like other correctional healthcare companies, has been accused of prioritizing cost-cutting over patient health, with little governmental oversight. CNN found that WellPath doctors and nurses often denied specialized testing, medication, and treatments. They have also failed to diagnose and treat psychiatric disorders, denied emergency room transfers for urgent cases, and allowed common infections and conditions to progress to the point of fatality.

Previous research also shows that the jail environment itself can lead to serious health crises. As a report from the Department of Justice explains, “certain features of the jail environment enhance suicidal behavior: fear of the unknown, distrust of an authoritarian environment, perceived lack of control over the future, isolation from family and significant others, shame of incarceration, and perceived dehumanizing aspects of incarceration.” People in jails are regularly denied contact with family and friends through the elimination of in-person visits and the high cost of phone calls, denied access to adequate medical care and nutritious food, exposed to unbearable heat and cold, and often subjected to the torturous conditions of solitary confinement.

Moreover, jails are often understaffed and/or have inadequately trained staff, and the vast majority of people working in jails are trained as correctional officers, not health providers or social workers. Despite years of evidence that suicide is the leading cause of jail deaths, many jail staff are not even trained in suicide prevention. Worse, some jail staff display indifference toward incarcerated people’s lives, often refusing to take their health concerns seriously and cutting off access to healthcare – with fatal consequences. For example, Clackamas County Jail workers were caught on camera laughing and joking about a military veteran overdosing in his cell. Even a nurse on duty reportedly spent less than five minutes with the man, who died after authorities finally took him to a hospital.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics data released yesterday emphasizes, yet again, the dangers of even short jail stays: 40% of jail deaths occur within the first week of a person’s incarceration. Given how just a few hours or days in jail can turn deadly, the report underscores the need to divert people away from jail – especially those with mental health and substance use disorders who are at increased risk – as well as the urgency of reducing the use of pretrial detention.