Warning: A painful road ahead for postal customers

Thanks to new regulations, the imminent spike in postage prices will fall heavily, and unfairly, on people in prison and jail.

by Stephen Raher, February 20, 2021

The dramatic tale of mail ballots during the November 2020 election had many people thinking about the mail for the first time in years. Now, though, as the election fades into the past, the post office isn’t on most people’s minds as much. But there is a huge group of people who can’t simply substitute the latest online communication or financial service for paper mail: incarcerated people and those who communicate with them.

In a time when consumer advocates warn to avoid filing your taxes on paper, people in prison and jail have no alternative. Want to monitor your credit history to guard against identity theft? It takes a few minutes online; unless you’re in prison, in which case you’ll have to mail a paper form to the credit bureaus and hope that the response makes it through the prison mailroom. Need to apply for a state-issued ID, student financial aid, public assistance, or just about anything else? Most often you’ll be directed to a website, but if you’re incarcerated you’ll need to keep turning over proverbial rocks, searching for a paper-based option.

With this general background in mind, let’s turn to a largely-overlooked change that could spell big trouble for users of the mail, particularly for those with low incomes. Under federal law, postal rates are set under a variety of complicated rules, overseen by the Postal Regulatory Commission (PRC). For years, the cost of a first-class stamp has been governed by an inflation-linked price cap: the USPS could seek permission to raise rates each year, but not beyond the rate of consumer inflation. After years of deliberation, the PRC issued a massive ruling in late November, establishing a new system that most experts warn will result in faster-growing postage rates.

Adding insult to injury: Obviously, any price increase is unwelcome news to people who use the mail. But the rationale underpinning the new price structure is a particularly bitter pill for incarcerated consumers. Setting aside some of the more esoteric parts of the PRC’s ruling, the leading justification for new price hikes is the issue of “mail density.”

Mail density works like this: the USPS is required to deliver to more addresses (or “delivery points,” in postal regulatory lingo) each year. As the overall volume of mail declines and the number of delivery points increases, the USPS’s cost to deliver each piece of mail goes up. Given this well-documented dynamic, the PRC decided that stamp prices should be allowed to increase to compensate for this “decline in mail density.”

So, we’re all going to pay more for stamps because of decreasing density–but what delivery point is more dense than a typical prison, where hundreds or thousands of people receive their mail at one address? From a strictly economic view, the new pricing system is logical: the American postal system is based on a theory of uniform rates, where anyone sending a letter pays the same amount, regardless of the path that the letter travels. Under this thinking, declines in density caused by sprawling new suburban developments are appropriately shared by all mailers, even those in densely populated cities or correctional facilities. But as a matter of basic fairness, something is awry. Incarcerated people are not contributing to the USPS’s declining density problem and they have no ability to mitigate increased postage rates by seeking electronic alternatives. But they stand to be the demographic most disadvantaged by the sharp price hikes likely to come later this year.

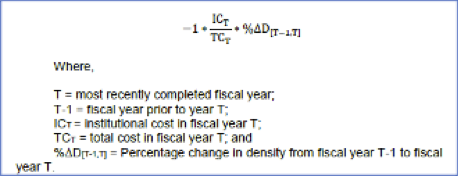

What does this mean for prices? The mechanics of the new rate procedure are so complicated as to be laughable. For example, the actual amount that stamp prices will increase due to the new density rate authority is determined by the following formula:

Not being gifted in math, I can’t give you a good explanation of this formula, but experts who study postal economics predict rapid and steep price increases. And the pandemic is making things worse. As explained in the previous section, the basic point of the complicated formula is to allow for greater price increases the more that mail density declines. What happened during the pandemic? Less mail was sent, and thus density took a nosedive.

As explained by the Save the Post Office blog, when the PRC issued its ruling, tentative calculations suggested that the density formula would probably yield a rate hike of 1.3% in 2021. But when the pandemic-depressed mail volume is plugged into the formula, it results in a potential price hike over three times as large (4.5%).

When other potential rate-drivers are taken into account, USPS could seek a mid-year price hike of around 5.5%. Based on the current first-class rate of 55c for a one-ounce letter, a 5.5% increase would be around 3c, but under the USPS’s ill-advised rounding policy (which we strongly opposed), the increase would be rounded up to the nearest five cents, potentially resulting in a new price of 60c to mail a letter. That’s about equal to the average hourly wage earned by incarcerated people in non-prison-industry certified jobs.

Prices go up as quality goes down. To make matters even worse, prices are going up at the same time that mail quality (i.e., speed of delivery) is getting really bad. For this, we can thank Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, a crony of the former president whose legendary conflicts of interest remain a stain on his tenure to this very day.

Unsurprisingly, Postmaster General DeJoy is on a seeming mission to destroy the USPS, recently announcing even greater service cutbacks that threaten to make mail even slower and less reliable than it is today.

What can you do about it? Unlike the criminal justice system, where power and decision-making is spread over hundreds of jurisdictions, postal policy is ultimately controlled by one body: Congress. There are currently moves in Congress to address mismanagement of the USPS, but when debating postal reform measures, lawmakers need to hear the unique burdens faced by incarcerated people.

Currently, there are two ways you can tell Congress to act. You can support efforts to remove Postmaster DeJoy, and you can tell your members of Congress to act immediately to improve the USPS finances without extracting more money from incarcerated people and their families. A general hearing on postal reform measures will take place in the House Oversight and Reform Committee on February 24. Committee members should keep the needs of incarcerated mailers in mind while crafting legislative proposals. For starters, this should include broad measures to stabilize the cost of sending first-class letters. More targeted reforms could include exempting incarcerated people from the new density-based rate increases, or (ideally) subsidizing postage for people in prison and jail.

I wonder if mail to and from correctional facilities can be subsidized by the government somehow? If the state deems individuals in need of sanction and rehabilitation, shouldn’t providing postage be part of that process? An inmate needs to communicate with the outside world, if anything even just to make arrangements for housing, a job, etc., upon release. To prevent abuse, only a certain amount of postage would be provided to offset the costs of routine required business inmates and others helping them run into.

This hits me right in the heart as Peter knows from past emails. It’s not just USPS, state prisons take a huge cut from what they call bake sales, ie. next month they get to order from Albertsons and Costco and are charging inmates 70% more than anyone not incarcerated. I understand they need to charge a little more due to delivery costs but this is ridiculous. Commissary has gone up with less things to buy, Chow serves enough to feed an 8 year old at each meal, quarterly packages are slow getting them to the prisons. Some inmates have been waiting since December to receive their order from Union Supply, not to mention you can wait on hold 2-3 hours. Not every immate has family or others to put money on their accounts, they barter cheap soap etc. just to get some rice or something to keep them from not starving. If you are not an active advocate or you don’t have someone you love in prison, you have no idea what really goes on!