Advocacy Spotlight: The Humanization Project

Advocates in Virginia are leveraging their own lived experience and the voices of thousands of other systems-impacted people and their families to make sweeping changes to the state’s prisons. Here’s how they’re doing it.

by Emmett Sanders, December 2, 2024

People who go through the criminal legal system often feel as if their humanity is being ignored. These feelings are more than justified. Dehumanization is not simply a side effect of incarceration: it is intentional and has been a part of prisons in the United States since the first brick was laid. Prisons in early America were so focused on keeping prisoners isolated and anonymous that they “required inmates to wear hoods whenever overseers moved them around the penitentiary.” While some things have changed, stripping prisoners’ identities remains a main component of incarceration in America.

According to activists like Johnny Perez, “The thing that they take the most, also, is actually your identity.” As the authors of The Roles of Dehumanization and Moral Outrage in Retributive Justice point out, “viewing others as lacking core human capacities and likening them to animals or objects may make them seem less sensitive to pain, more dangerous and uncontrollable, and thus more needful of severe and coercive forms of punishment.” Reducing incarcerated people to numbers or to the alleged acts that brought them to prison makes it easier to deny them civil rights and allows systems to justify harsher punishment, longer sentences, as well as the inhumane, often abusive conditions that prisons impose by design. Dehumanization allows policymakers to ignore the human impact of their decisions on people in prisons and their families. It also creates the false image that people in prison are incapable of rehabilitation.

When lawmakers don’t see people in prisons as fully human, it makes it much harder to change inhumane prison conditions and policies. That’s why an organization of systems-impacted advocates in Virginia, The Humanization Project, uses a framework of “humanization” to drive policy change. Humanization works to unflatten the identities of those impacted by incarceration in public narrative and political discussions, shifting focus away from people’s worst moments and toward the many statuses and roles that make them who they are. Through humanization, people are not just numbers or statistics; they are fully formed human beings with families who love them. They are children and parents, husbands and wives, grandmothers and grandfathers. This change in perspective can have a powerful impact on lawmakers.

The Humanization Project provides a powerful framework for advocacy

The Humanization Project has been working with the impacted community to reform Virginia’s justice system since 2017. Co-founded by Executive Director Taj Mahon-Haft and his partner Gin Carter while Mahon-Haft was still incarcerated, the organization began by noting that the “human consequence” of policy decisions was often left out of reform discussions. Informed by Mahon-Haft’s experience as a trained sociologist, The Humanization Project used a humanization framework, centered in empathy and common ground, to develop several strategies to change this dynamic, including:

- Using multimedia platforms to curate narratives and impacted person-produced research that provide human faces and voices for issues, and connecting those narratives with policymakers, advocates, and the public;

- Using community engagement and direct outreach to educate and inform impacted people and their families on how the legislative process works, what a bill will do, and the processes and procedures of system change;

- Leveraging their intersectionality as impacted advocates to facilitate human-centered discussions across a diverse array of partners in order to build capacity and coalition through commonality and compassion.

Entirely dependent upon the support and engagement of the justice-impacted community, this model helped The Humanization Project shift narratives, defuse fear-mongering attacks, and expand support for one of the biggest reforms in Virginia’s history, HB5148, which established a system for Earned Sentence Credits.

Anatomy of a victory: Earned sentence credit in Virginia

According to the Virginia Department of Corrections, when COVID-19 hit, the state’s prison population had been hovering at around 30,000 people since at least 2014.1 Advocates, organizers, and policymakers used litigation and proposed legislative changes to reduce prison populations. In the context of this struggle, lawmakers proposed HB 5148 to expand the use of earned sentence credits. In Virginia, as in other states, some people in prisons earn “good time” credits: for each day they spend incarcerated without disciplinary issues, they earn a certain amount of time off their overall sentence. Earned Sentence Credits, unlike good time credits, are based on merit and require participation in rehabilitative or educational programming, work, or service. Among other benefits, expanding the use of earned sentence credits can help reduce prison populations, make prisons safer, and reduce the chance of people returning to prison. Offering and incentivizing rehabilitative programming also better aligns with what crime survivors want. In Virginia, however, offense-based carveouts meant that thousands of people couldn’t earn sentence credits for participating in programming. HB 5148, the Earned Sentence Credit bill, more than tripled the amount of time most people could earn for participating in programming and applied retroactively, meaning people were awarded credit for programming they had participated in in the past. All in all, it offered an earlier release date for thousands of people in Virginia’s prisons.

Using a humanization model, and with the priceless engagement of community members and grassroots and civil rights organizations like the ACLU of Virginia, The Humanization Project produced videos and messages from people in prison to urge policymakers to pass HB 5148. When Gov. Youngkin forced a budgetary amendment that carved out people with certain offenses and reduced the number of people eligible for the rise in earned sentence credit by around 40%, The Humanization Project again lifted the voices of those most directly affected to fight against the change. The bill passed in October 2020, and was fully realized in May 2024 when the state’s new budget was signed into effect without the governor’s exceptions, expanding eligibility to another 7,000 incarcerated people.

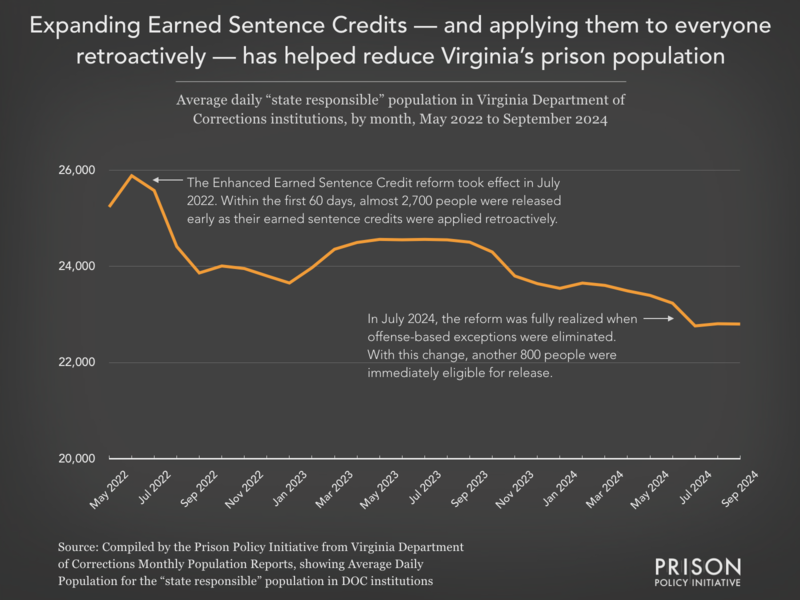

Including the 10,826 who had received immediate changes to their release dates when the bill took effect in July of 2022, nearly 18,000 people2 have had their release dates modified overall. Around 79% (or 7,329 out of 9,324) of people released from Virginia’s prisons in FY 2023 alone benefitted from earned sentence credits, with thousands more projected to be released through earned sentence credits in FY 2024. Overall, per the Virginia Department of Corrections’ monthly population reports, the state lowered its state-responsible population by around 12% between June 2022 (25,889) and September 2024 (22,802), contributing to the closure of four prisons. The implementation of earned sentence credit is also projected to save Virginia $28 million over the next two years. The Humanization Project notes this victory does not belong to them, but to the broader justice-impacted community in Virginia: as Taj Mahon-Haft points out, “We are proud to have been part of helping organize and engage people, but the progress only happened because impacted folks across the state shared their voices and humanity in ways that changed hearts and minds. Anyone who really gets to know the members of our community can’t help but want a more humane system.”

Humanizing future advocacy can strengthen reform

While many factors contributed to Virginia’s massive drop in prison population since the COVID-19 pandemic began, the passing of Earned Sentence Credit has played a huge role, as has the use of humanization as a framework for change. The Humanization Project is now applying this same advocacy model to other issues they’ve identified, such as their “Reentry Begins: Day 1 Inside” initiative, which focuses on creating earlier access to programming for people in prison. Currently, people may have to wait months or even years before accessing programming. With the passage of HB5148, earlier access to programming would mean incarcerated people could begin to accrue earned time and ultimately become eligible for release earlier as well, further amplifying the success of the changes to earned sentence credit. The campaign is also turning the lens of humanization towards protecting visitation quality and access for those in Virginia’s prisons and their loved ones, an effort that the Prison Policy Initiative’s advocacy department has supported through research.3 Focusing on humanization as a method of advocacy has proven effective in many contexts, and advocates across the country can use it in their own reform work.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the dehumanizing force of incarceration serves as a roadblock to reform by disconnecting policymakers from the human experiences of those in prison. Humanization is a framework that uses intersectionality, compassion, and common experience to implement meaningful, sweeping change by countering narratives that too often overlook the people in the policy. As the Humanization Project’s co-founder Gin Carter puts it, “This particular argument has been won with humanity conquering the day. We discuss the human impacts more while stereotypes, dog whistling and fear-mongering win out less often.”

Learn More

Learn more about good time and other ways to shorten excessive prison sentences in our report, Eight Keys to Mercy, and learn how mass decarceration does not make us less safe in Large scale releases and public safety, and learn more about combating carveouts that undermine effective justice reforms in our toolkit and webinar on charge-based exclusions.

Footnotes

-

We used data from the Virginia Department of Corrections monthly population reports here as it provides the most recent data. However, the Bureau of Justice Statistics consistently reports significantly higher populations, including in 2014 (37,544), 2022 (27,162), than the Virginia Department of Corrections. The reason for this is unclear. ↩

-

Per reports, 10,826 received earned sentence credit initially, with another 7,000 receiving retroactive eligibility with the signing of the budget in May of 2024. ↩

-

Currently in Virginia, visitation can be suspended for a host of reasons, severely limiting incarcerated peoples’ access to the positive impacts of family contact. ↩

To anyone who cares about people,

My family and I have walked with my son for 22 years of incarceration. My son made a stupid mistake and has served a life sentence when no one was killed. My son was on drugs and alcohol when he committed his crimes. We have petitioned the Governor with the appropriate documents (Conditional Pardon) which included an apology to the victim. My son was turned down for a conditional pardon, but President Joe Biden’s son was granted a full pardon. How can this be? I am a Disabled Veteran, and I have served this country as well. If the President can pardon his son, then he can pardon mine. We are living in a very corrupt time in our nation. The people are going to get tired of being restrained and lied to by our leaders. We have to stand up for the truth and against what is false. Our children are supposed to be rehabilitated, but they are not! They are housed for State funding. Our leaders do not want our children reunited to us because they receive money for their incarceration. I know our children are not being rehabilitated because I am a prison minister who has seen the lack of care and concern firsthand. Enough is enough! Send John Tyler Dobson #1022523 home immediately! John William Dobson

First I would like to applaud all the hard work and tireless efforts of these wonderful advocates. I have personally been affected by a sibling going to prison at age 14 until he was 24. This was due to an attempt to thwart juvenile crime. 10 to the door was the nickname, and despite no harm to victims and the law being repealed only three years after implementation, no cases were allowed to be retroactive. No rehabilitation, no resources, no parole officer to offer guidance. Now his skills include drug dealing and failing to pay taxes. He is 41 yet spent 24 of those years incarcerated.

Thanks to the new earned good time credits he may be released 10 years early, as he is serving 18 years in Federal prison. The cost involved to house offenders, especially as they age and poor conditions amplify health issues is exorbitant. Tax payers need real life human experiences and not blind fear to learn that the tough on crime with long sentences is a dead end.

Please continue to educate people and involve communities to humanize offenders. I love my brother and the pain and loss of 24 years of life wasted behind bars saddens me and has impacted my family deeply. I have made a financial contribution and share this project with others to help keep the momentum going.

I would encourage all citizens to do what they can, as one life saved actually saves entire family’s heartbreak.

Thank you.

Kristina Prince