How journalists can push back on prison and jail “gag rules”

Broad policies prohibiting prison and jail staff from talking to reporters are common but likely unconstitutional. Here’s how reporters can push back against these policies.

by Mike Wessler, December 13, 2024

Journalists play an essential role in spotlighting the terrible conditions and circumstances that incarcerated people face every single day. It’s perhaps no surprise then that corrections departments routinely make it harder for reporters to get information about their facilities. Some of the most common obstacles to reporting on jails and prisons are “gag rules” that forbid anyone on staff from talking to journalists without approval from their supervisor or a public information officer (PIO).

Here’s the dirty little secret about these gag rules: despite being incredibly common, they are almost certainly unconstitutional and unenforceable. In fact, within the last year, journalists have successfully challenged gag rules to provide more transparency on what is happening within carceral facilities and make more thorough reporting possible.

In this briefing, we reviewed research from the Society of Professional Journalists and from Frank LoMonte,1 currently Co-Chair of the Free Speech and Free Press Committee of the American Bar Association’s Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice, to show how common and far-reaching these gag rules are in the criminal legal system. We also explain why courts have consistently struck down gag rules, and provide an actionable pathway for journalists to challenge them.

What are “gag rules” and how common are they?

A gag rule seeks to do exactly what it sounds like: keep people from talking. In this case, gag rules deter jail and prison employees from speaking to the media.

In corrections departments, gag rules generally take three forms:

- An explicit policy from the department’s legal team that lays out specific rules, procedures, and punishments for failing to follow the policy when communicating with journalists.

- Directives from a public information officer that tell employees how to respond if they’re contacted by a member of the media.

- An organizational culture of silence, where there isn’t a specific written policy or directive but rather a general understanding that staff should not talk to journalists.

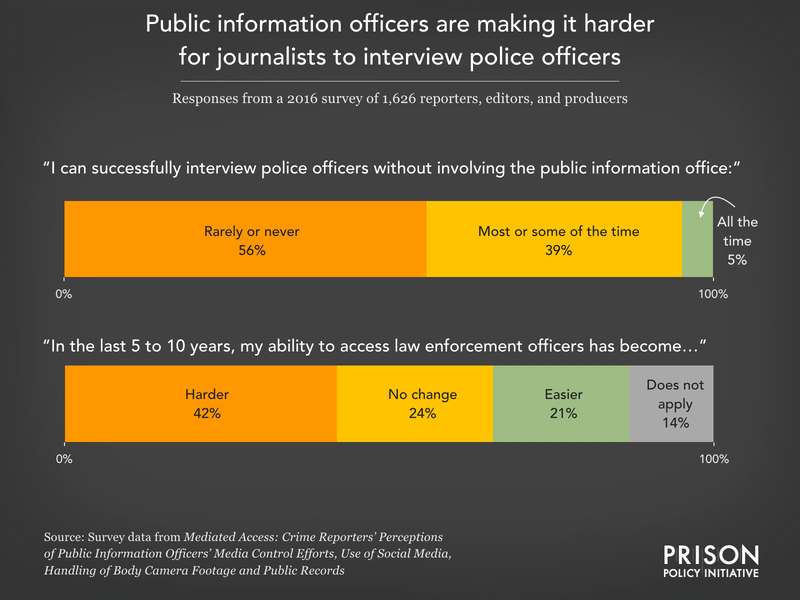

Gag rules are incredibly common.2 A 2016 survey by the Society of Professional Journalists found that more than 55% of journalists covering law enforcement agencies said they are never or rarely allowed to interview officers without a public information officer’s involvement. Additionally, 41% of surveyed journalists said that accessing police officers and law enforcement agents has gotten marginally or significantly more difficult in the last five to ten years.

Policies from correctional agencies are often quite explicit in prohibiting staff3 from speaking with the press:

- The Alabama Department of Corrections’ policy manual says: “If a reporter or news media representative contacts an employee of ADOC for an interview, that employee or their supervisor shall notify the PIM (public information manager) and gain approval before speaking with the news media.”

- In Louisiana, the Department of Corrections’ policy manual says: “Staff shall refer all media inquiries to the unit head or designee.”

- In its policy manual, Arizona’s Department of Corrections states: “Department staff shall refer all media requests to the Media Relations Director and the Deputy Media Relations Director.”

- Similarly, Idaho’s Department of Correction policy says, “Requests for interviews with staff will be referred to a PIO.”

These are just a handful of examples that can be found by reviewing departments of corrections’ policy manuals, and there is every reason to believe that local jails have similar — if not even more restrictive — rules on the books.

Courts have routinely struck down stringent “gag rules”

Even though gag rules are incredibly common, courts have consistently struck down blanket policies that restrict public employees from talking to members of the press without authorization.4 In his review of court rulings on this issue, LoMonte found nearly two dozen cases in which courts have rejected policies that require government employees to get approval before speaking to the media.

Courts — including the Supreme Court of the United States — have looked most harshly upon rules prohibiting speech before it can be heard as a form of censorship known as “prior restraint.” The Supreme Court has said government agencies must show an overwhelmingly compelling reason to prohibit employees from speaking publicly. Importantly, federal courts have clarified that avoiding accountability does not constitute an overwhelmingly compelling reason.

At least four federal circuit courts5 have struck down broad restrictions on government employees speaking publicly, and two additional ones6 have suggested they would act similarly. In fact, no federal court of appeals has upheld these broad restrictions.

It is worth noting that the courts haven’t struck down all prohibitions on public employees speaking to the press, just those determined to be overly broad. For example, agency policies that don’t outright ban unapproved communication between the press and employees, but do urge caution or encourage employees to consult with PIOs, would likely pass constitutional muster because they are not as stringent and lack a threat of punishment.

How journalists can fight gag rules

Most journalists who have covered prisons, jails, or other aspects of the criminal legal system have almost certainly encountered gag rules. Often, these rules feel like insurmountable obstacles that hinder an otherwise promising story. Fortunately, that doesn’t have to be the case. If you run into a gag rule, here’s a clear strategy to overcome it or, if necessary, challenge it in court.

First, you should aim to get prisons, jails, or other law enforcement agencies to do one of two things:

- Acknowledge in writing that its “policy” around employees talking to the press isn’t really a policy at all but more of a request or recommendation that has no consequences for violating it and is otherwise unenforceable.

- Admit that it’s a formal policy that includes the threat of punishment and, thus, is ripe for a legal challenge.

To accomplish this, you should request a written copy of the policy. In addition, you should ask who drafted the policy, how it is enforced, and what the punishment is for an employee or journalist7 who violates the rule. You may need to file a public records request to get some of this information.

Once you have that information, consider the following issues:

- Is there a written policy? If not, you should get documentation from the agency indicating this fact and use this information to assure agency employees that speaking to the press is not prohibited.

- What does the policy look like? With this question, you want to understand whether the policy was created through the facility’s formal drafting process and is enforced, or whether it was more of an informal request made to staff.

- Who drafted it? This question will allow you to assess how seriously the policy has been thought out by the agency. Policy from the legal department has likely gone through a formal implementation process, while a guideline from the PIO likely has not followed that official pathway.

- What are the consequences of violating it? This will indicate whether employees or journalists who violate the rule should be worried about punishment.

Once you have this information, you have to make a judgment call:

- If it appears the agency has no real policy, or it is a policy that there are no repercussions for violating, you can take that information to agency employees and explain the situation. There is always the possibility employees will fear speaking to reporters simply because they know their superiors will not like it or will not like what they say to the reporter. But knowing the rules may give the reporter more leverage.

- If it appears the agency has an official policy with explicit consequences, your first step should be to investigate whether similar policies have been struck down by federal courts in your area. If so, bring this to the attention of the agency’s legal department to make sure they know that they are at risk of a lawsuit. This may be enough to get them to abandon the policy. If that doesn’t work, you will likely need to challenge the policy in court.8

If you determine a lawsuit is necessary to overcome a gag rule, you should first contact your newsroom’s legal team to discuss the matter. You should also check out the Yale Law Media Information & Access Clinic’s website, which has more information and resources. This organization also provides legal assistance in some cases involving government agencies inappropriately hiding information from the public and press and wants to hear from journalists encountering these gag rules.

These gag rules, while incredibly common and frustrating, don’t have to be the end of your story. This strategy and these resources can help you get to the truth about what is happening within the walls of prisons and jails and your community, and provide much-needed public scrutiny of how incarcerated people are treated.

Footnotes

-

Journalists who want a deeper analysis of the authority (or lack thereof) to prevent government employees from speaking to the media should also check out this law review article from LoMonte. ↩

-

While this piece focuses on prisons and jails, these gag rules are common throughout other government agencies as well. ↩

-

Some prisons and jails sometimes have policies that also prohibit incarcerated people from speaking to journalists. ↩

-

For a more thorough review of case law on this issue, see Frank LoMonte’s law review article on this topic. ↩

-

The Second, Fifth, Ninth, and Tenth circuits. ↩

-

The Third and Seventh circuits. ↩

-

While it is less common than punishing employees for unauthorized communications with members of the press, some public agencies also punish journalists who don’t follow its processes. The most common punishment in these circumstances is “blacklisting” or prohibiting all future communication with that journalist. ↩

-

Journalists obviously also have the ability to treat employees of the carceral facility as whistleblowers, but should take appropriate precautions to protect their sources. ↩