20 years is enough: Time to repeal the Prison Litigation Reform Act

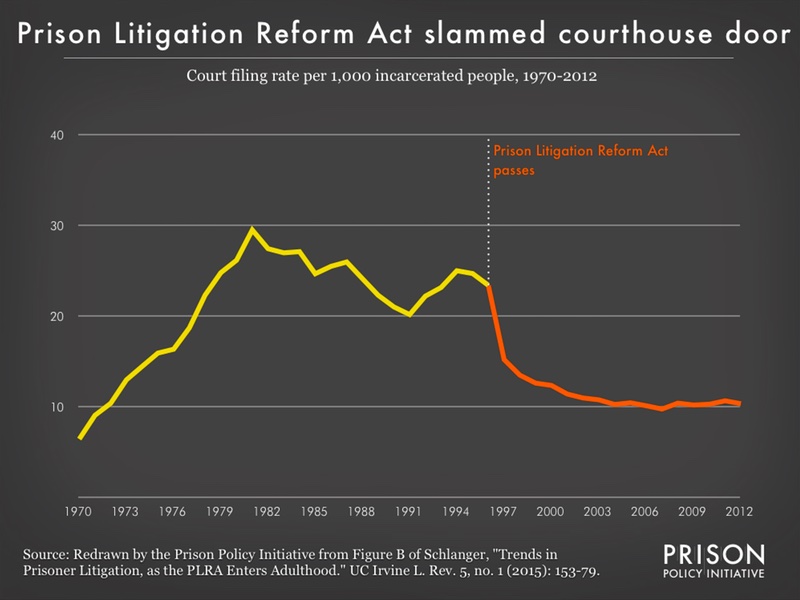

Professor Margo Schlanger's data shows how the Prison Litigation Reform Act closed the courthouse door on incarcerated people seeking protection of their civil rights.

by Meredith Booker, May 5, 2016

This article was updated in 2021 in a major report with more recent data about the impact of the Prison Litigation Reform Act. That version should be used instead of this one.

The Prison Litigation Reform Act, which made it much harder for incarcerated people to file and win civil rights lawsuits in federal court, was a key part of the Clinton-era prison boom. It turned 20 years old last week.

Law Professor Margo Schlanger has an important article using 40 years of court and imprisonment data to explore the impact of the Prison Litigation Reform Act on incarcerated people’s access to the courts:

The filing rate by incarcerated people dropped significantly after the passage of the Prison Litigation Reform Act. And ironically, despite Congress’ fears of a prison lawsuits flooding the courts, this data that controls for the size of the prison population shows that in 1996, when the Prison Litigation Reform Act was passed, fewer lawsuits per 1,000 incarcerated people were being filed than during the ten year period of 1979-1988.

After the passage of the law, court filings by incarcerated people plummeted. This drop is largely attributed to several key provisions in the Prison Litigation Reform Act:

- Incarcerated people must exhaust all internal administrative grievance processes available to them within the correctional facility before taking their case to court. Working through these administrative processes can be complicated, have difficult deadlines, and often be fruitless.

- Suits alleging only mental or emotional harm are restricted. (Suits about physical injury are still allowed.)

- Courts are no longer allowed to waive court fees for incarcerated people, instead requiring installment payments. Additionally, an incarcerated plaintiff who has had three previous lawsuits dismissed can be required to pay in advance.

- When a lawsuit succeeds, the statute sharply limits the amount of litigation costs that the court can order the facility to pay the incarcerated person’s attorney. This reduces the number of lawyers willing to take good winnable cases on behalf of incarcerated people. In 2012, just over 5% of incarcerated people’s civil rights cases were represented by attorneys. (By contrast, 65% of non-incarcerated civil rights plaintiffs and 97% of labor and employment cases plaintiffs were represented by attorneys.)

- Places limits on the ability of the courts to change prison or jail policy.

These provisions shut incarcerated people out of the courts, to lasting effect. As Schlanger explains:

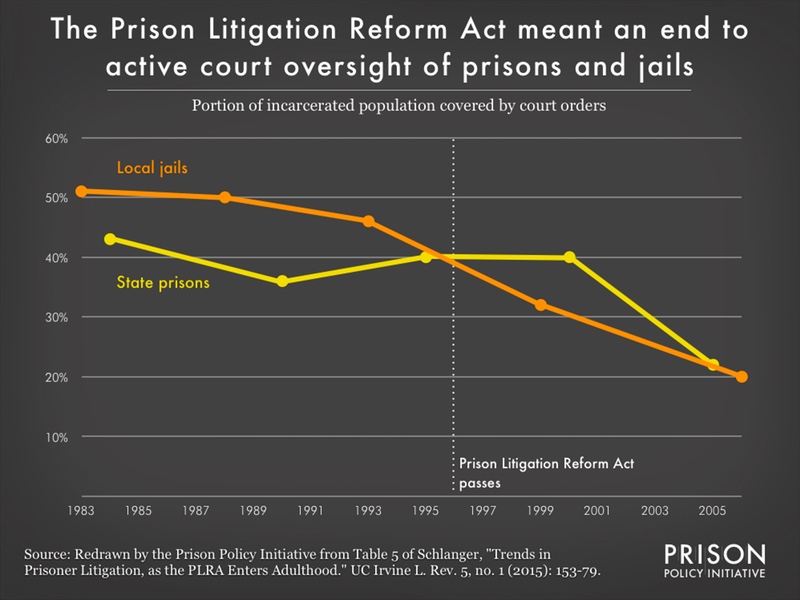

Since the 1970s, court orders have been a major source of regulation and oversight for American jails and prisons–whether those orders entailed active judicial supervision, intense involvement of plaintiffs’ counsel or other monitors, or simply a court-enforceable set of constraints on corrections officials’ discretion.

And her data illustrates that effect:

As existing orders expired, the portion of the incarcerated population that was covered by court ordered protection dropped sharply a few years after the Prison Litigation Reform Act. By the end of 2006, only 7 states had system-wide court order coverage in their jails or prisons.

The drafters of the Prison Litigation Reform Act argued that the goal was to limit frivolous lawsuits, which they claimed where rapidly increasing. While the number of prison lawsuits was rising in the 1990s, so too was the prison population. In fact, as Schlanger’s data in the first graph above reveals, court filings were – controlled for the size of the prison and jail population – actually lower than in the previous decade.

Now, at a time when the public and many elected officials are questioning the wisdom of mass incarceration, it’s time to reconsider the Prison Litigation Reform Act and the very idea of closing the courthouse doors to cries for justice.

Additional work about the Prison Litigation Reform Act by Margo Schlanger includes Civil Rights Injunctions Over Time: A Case Study of Jail and Prison Court Orders and Inmate Litigation.

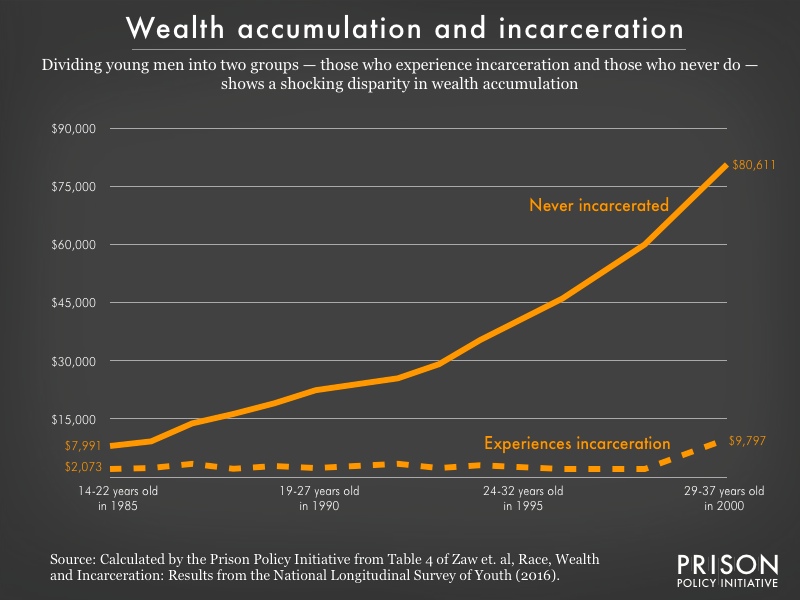

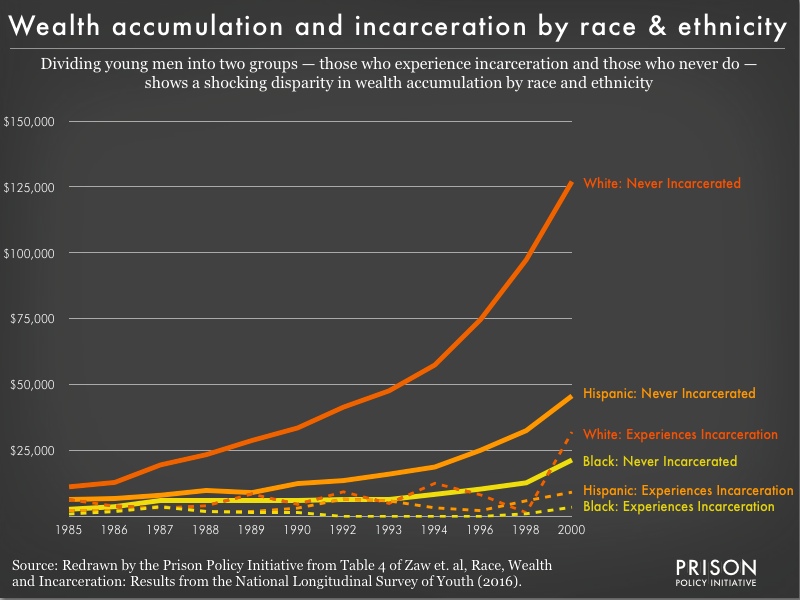

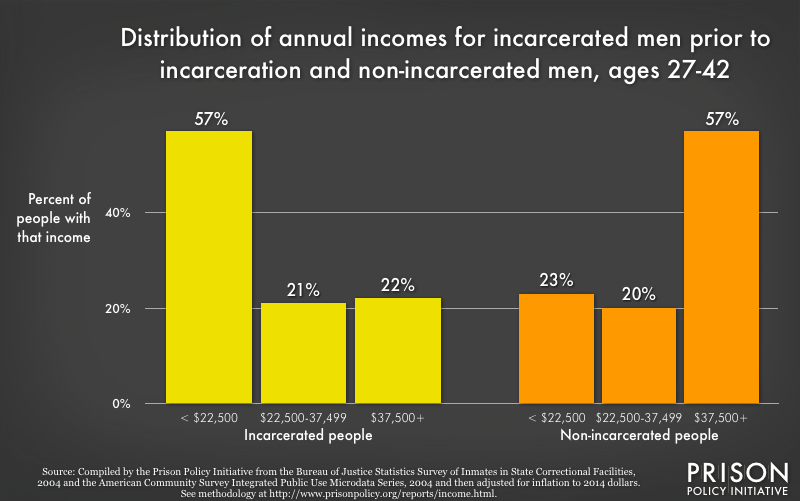

When it comes to the economic impacts of incarceration, one point becomes very clear: men who experience incarceration maintain lower levels of wealth throughout their lifetimes compared to men who are never incarcerated. This disparity is present before, during, and after a person is incarcerated. (The data stops in 2000 because of small numbers of survey respondents for some subgroups; the authors note that the wealth trends remain in the years that followed.)

When it comes to the economic impacts of incarceration, one point becomes very clear: men who experience incarceration maintain lower levels of wealth throughout their lifetimes compared to men who are never incarcerated. This disparity is present before, during, and after a person is incarcerated. (The data stops in 2000 because of small numbers of survey respondents for some subgroups; the authors note that the wealth trends remain in the years that followed.)

Previous research in

Previous research in

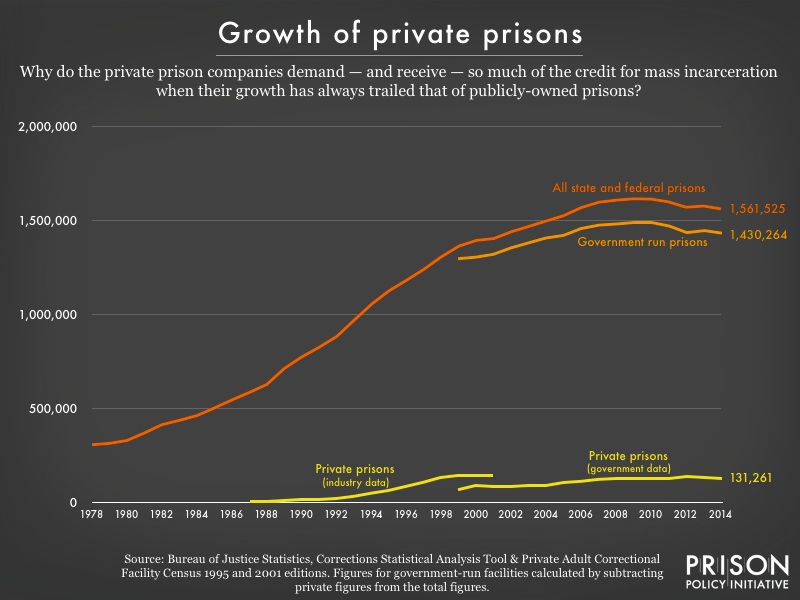

Note that the federal government didn’t even bother to track the size of private prisons until 1999 and that we calculated the size of the government-run prisons by subtracting the private prisons from the total. The data from 1987 to 2001 was collected and published by an academic in Florida with a

Note that the federal government didn’t even bother to track the size of private prisons until 1999 and that we calculated the size of the government-run prisons by subtracting the private prisons from the total. The data from 1987 to 2001 was collected and published by an academic in Florida with a

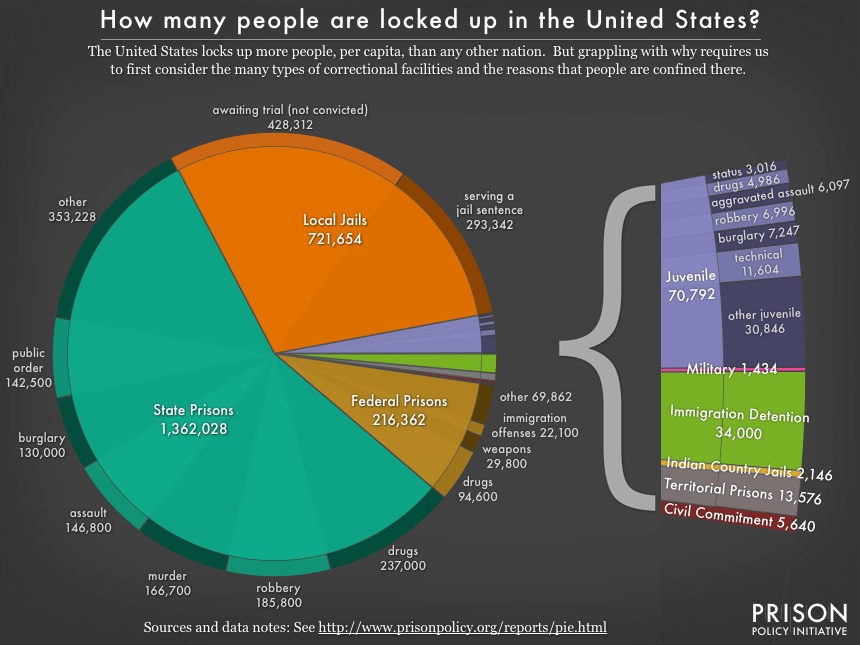

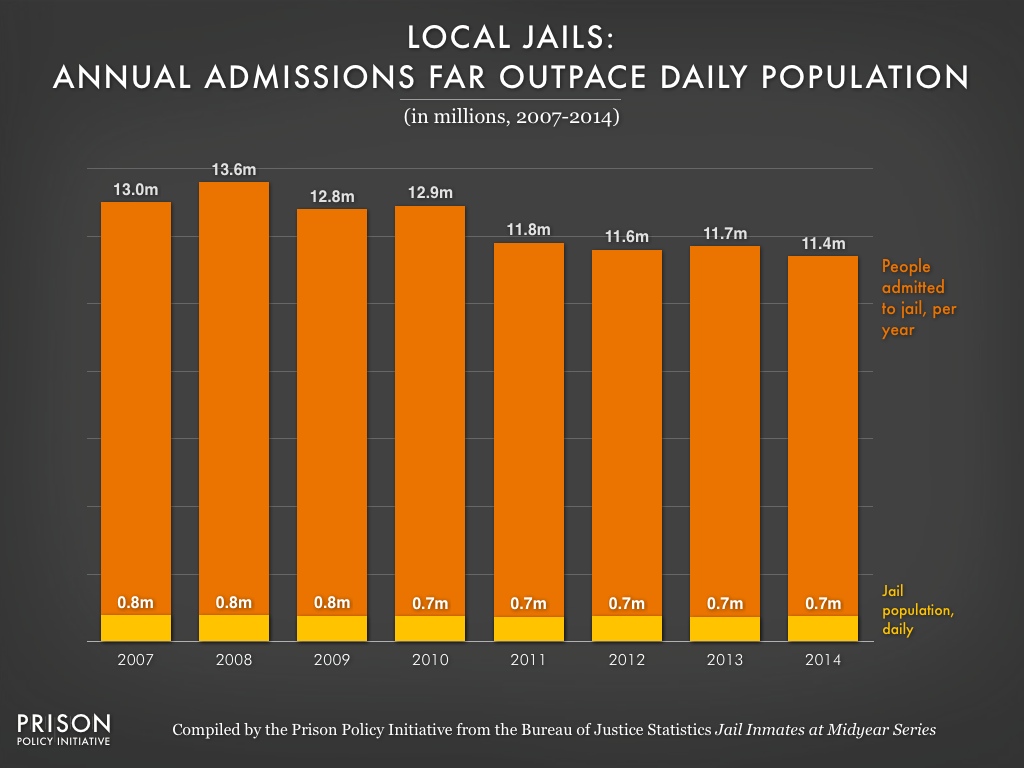

Addressing the problem of jails means grappling with the tremendous churn through jails. How can we lessen the numbers who enter jails and reduce the time that 11 million people spend there each year?

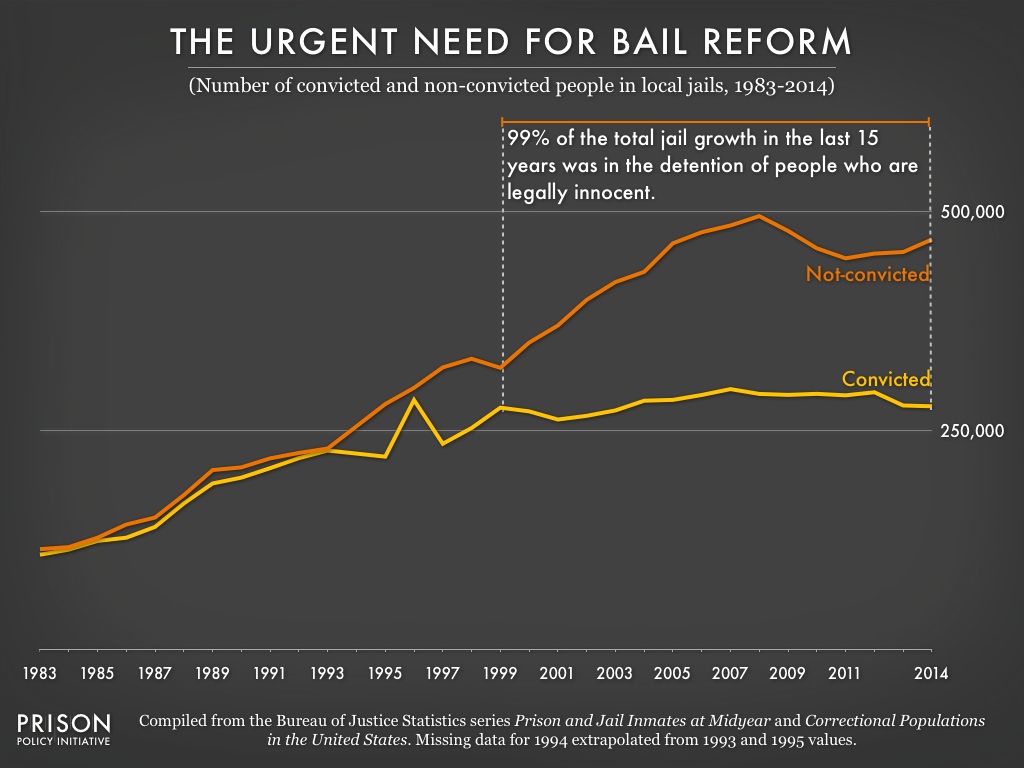

Addressing the problem of jails means grappling with the tremendous churn through jails. How can we lessen the numbers who enter jails and reduce the time that 11 million people spend there each year? Virtually all of the growth in the jail population has been in the number of legally innocent people who are detained in jails.

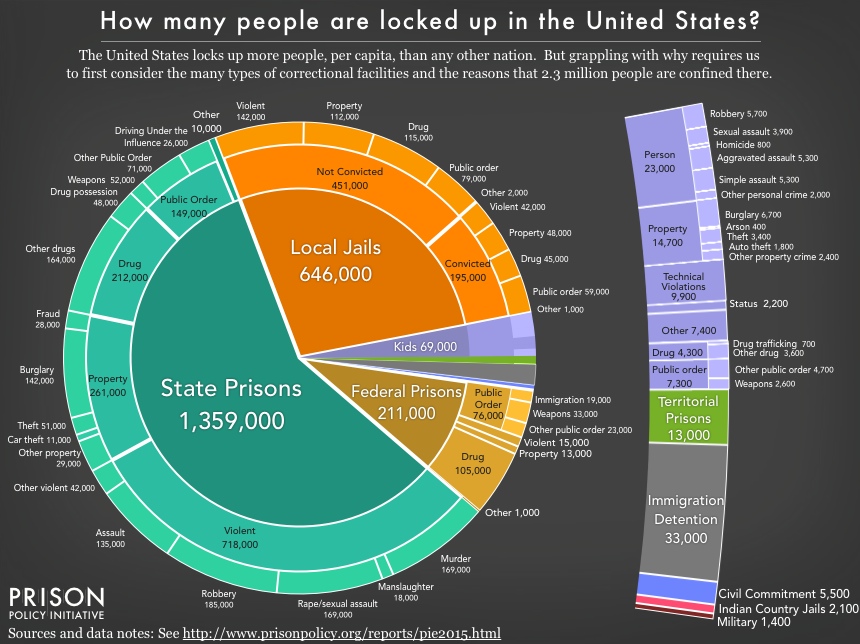

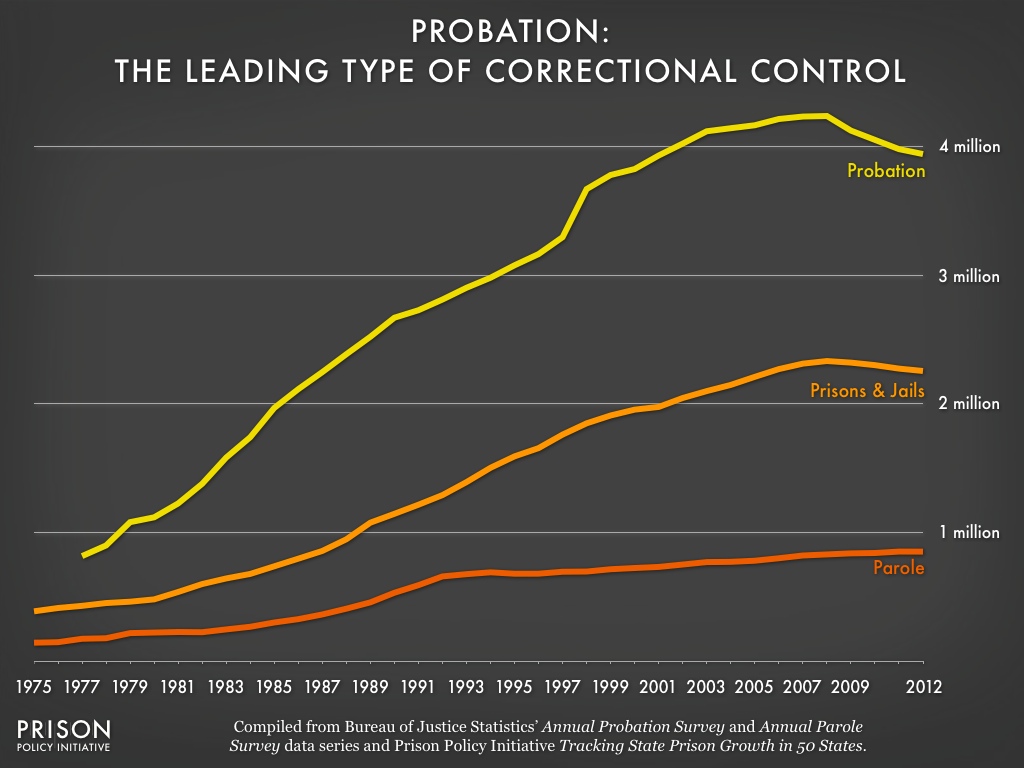

Virtually all of the growth in the jail population has been in the number of legally innocent people who are detained in jails.  Since the beginning of the statistics almost 40 years ago, the probation population has grown much more quickly than either the number of people on parole or the number of people in federal, state and local prisons and jails. While about 2.3 million U.S. residents were behind bars in 2012, almost 4 million residents were under probation.

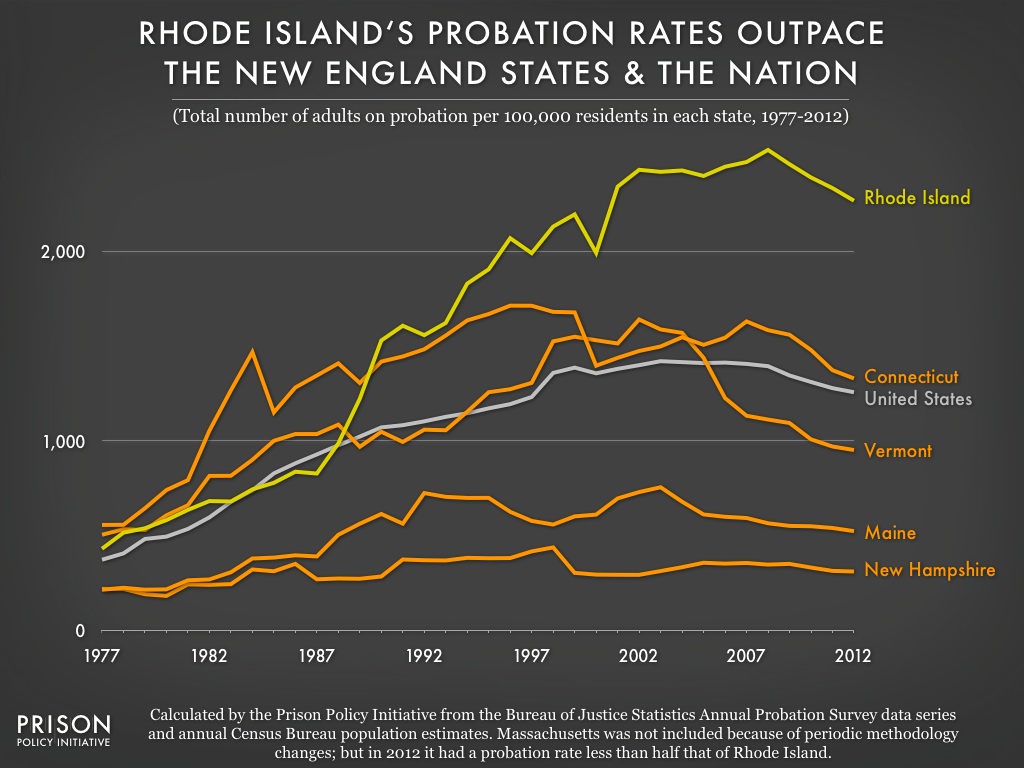

Since the beginning of the statistics almost 40 years ago, the probation population has grown much more quickly than either the number of people on parole or the number of people in federal, state and local prisons and jails. While about 2.3 million U.S. residents were behind bars in 2012, almost 4 million residents were under probation. The rate of probation in Rhode Island is more than twice as high as the rate of probation in most other New England states. (Massachusetts was not included in the graph above because the state changed its reporting methods multiple times during the previous decade. However, in the most current available data, Massachusetts reported a rate of 1,033 adults on probation per 100,000 residents, less than half Rhode Island’s rate of 2,268 per 100,000 residents.)

The rate of probation in Rhode Island is more than twice as high as the rate of probation in most other New England states. (Massachusetts was not included in the graph above because the state changed its reporting methods multiple times during the previous decade. However, in the most current available data, Massachusetts reported a rate of 1,033 adults on probation per 100,000 residents, less than half Rhode Island’s rate of 2,268 per 100,000 residents.)