New report Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2022 provides the most comprehensive look at U.S. incarceration since the start of the pandemic

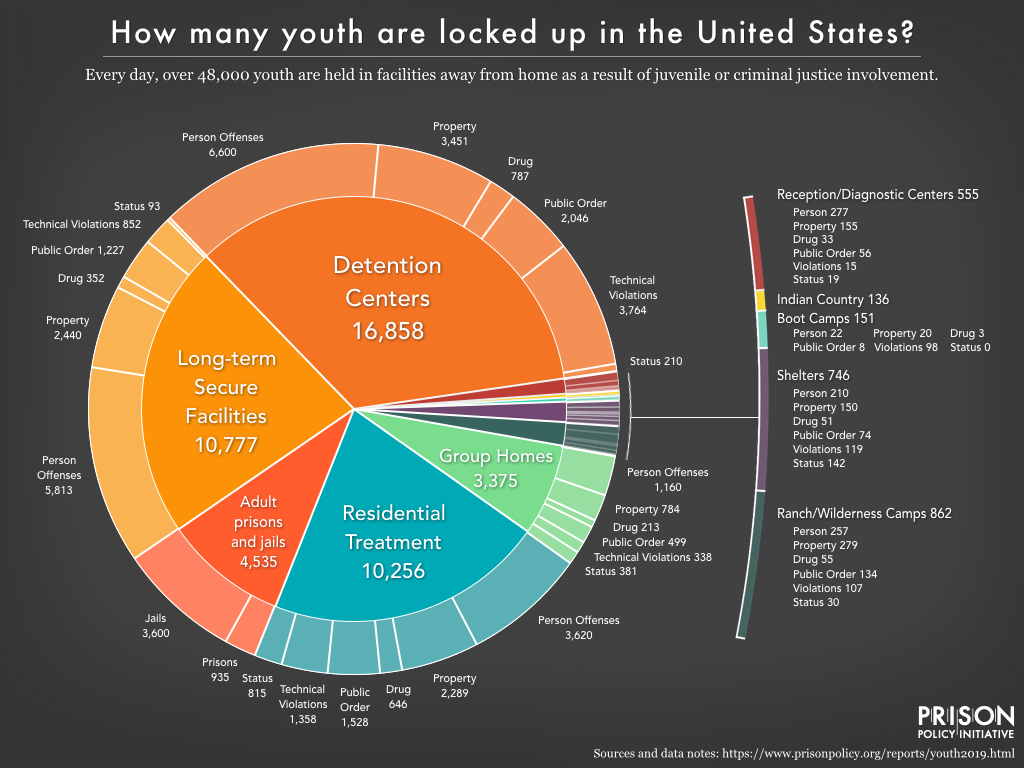

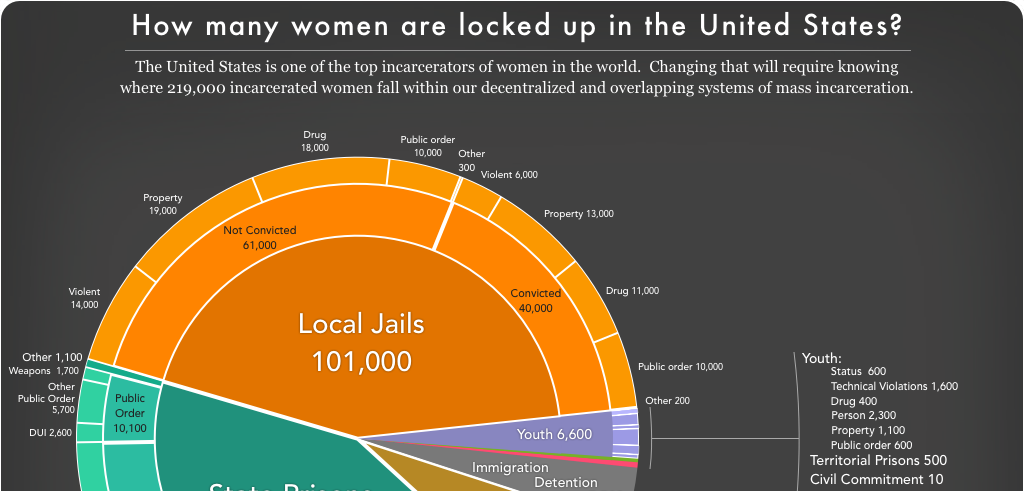

The report includes 31 visualizations of criminal justice data, exposing long-standing truths about mass incarceration in the U.S.

March 14, 2022

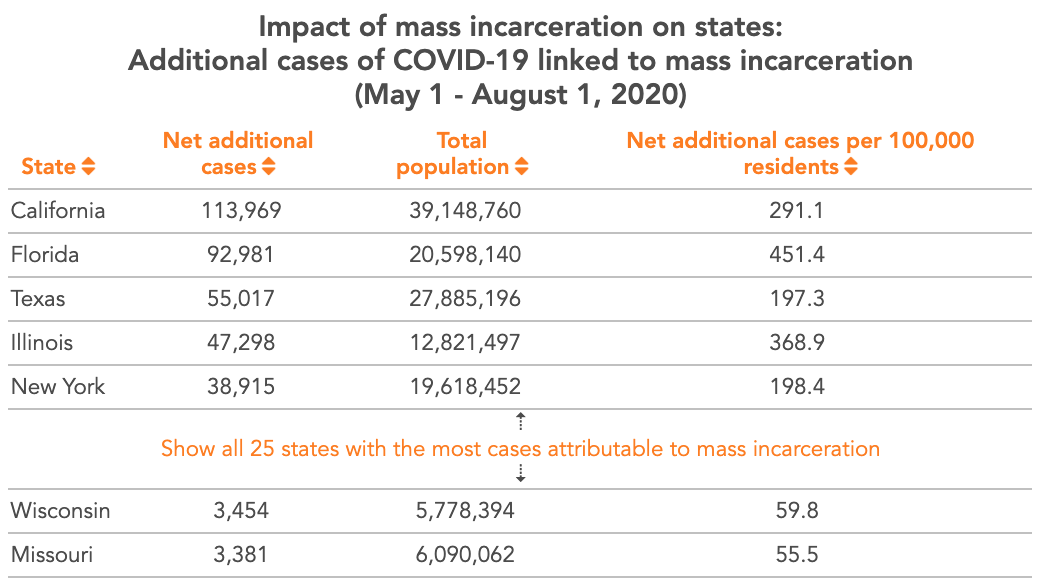

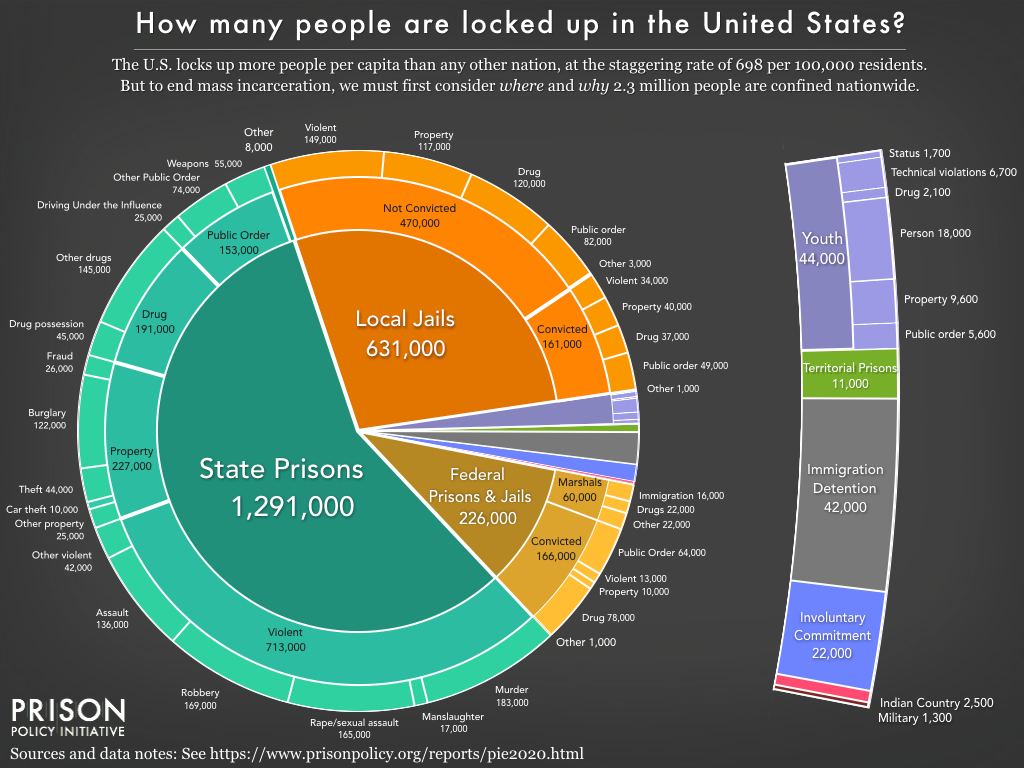

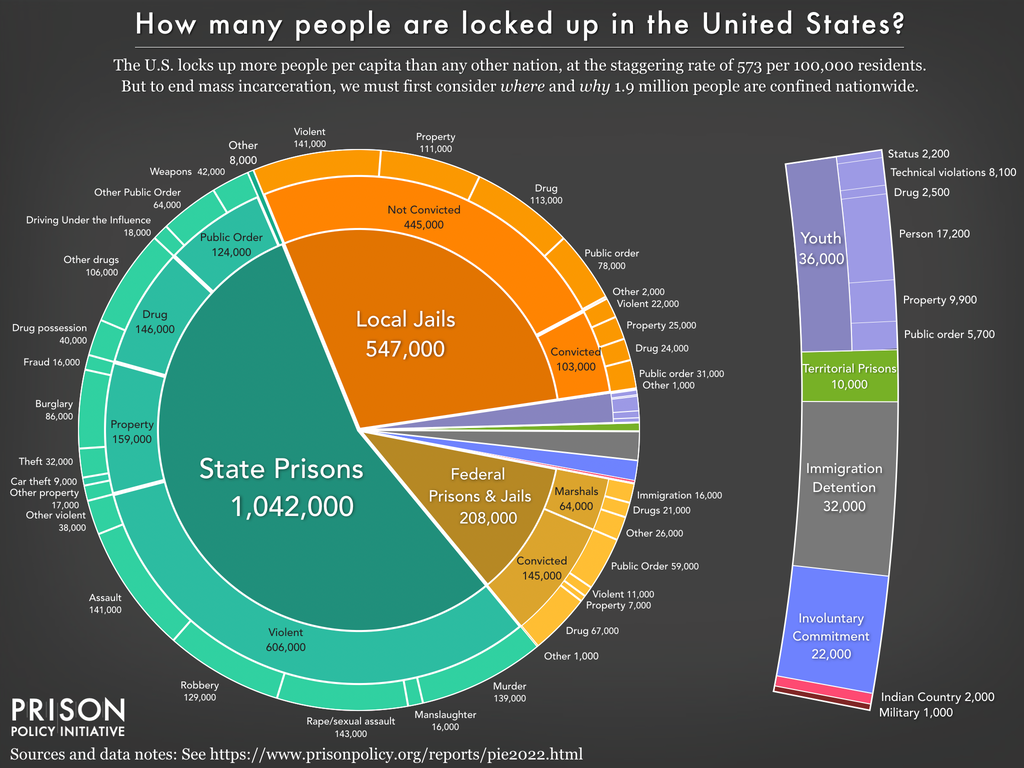

Today, the Prison Policy Initiative released Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2022, compiling national data sources to offer the most comprehensive view of how many people are locked up in the U.S. — and where they are being held — since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The report explains how the pandemic has impacted prison and jail populations, and pieces together the most recent national data on state prisons, federal prisons, local jails, and other systems of confinement to provide a snapshot of mass incarceration in the U.S.

Highlights from the report include:

- Prison populations fell by about 16% during the pandemic. However, 10% fewer people were released from prison during 2020 than in 2019, and preliminary data suggests that fewer still were released in 2021, meaning that people leaving prison did not drive the population drop. Instead, the reduction was due to reductions in prison admissions, largely due to pandemic-related slowdowns in the criminal legal system.

- Local jail populations fell about 13% during the pandemic. Since then, a sample of over 400 jails shows that jail populations are returning to pre-pandemic levels and more than a quarter of jails have higher populations today than before COVID-19.

- In total, roughly 1.9 million people are incarcerated in the United States.

“Even when the U.S. prison population was at a historically low point in the pandemic, we were still locking up far more people per capita than any other country on earth,” said Wendy Sawyer, Research Director for the Prison Policy Initiative and co-author of the report. “It’s important for people to understand that the temporary population drops during the pandemic were due to COVID jamming the gears of the criminal justice system — not because of any coordinated actions to reform the system.”

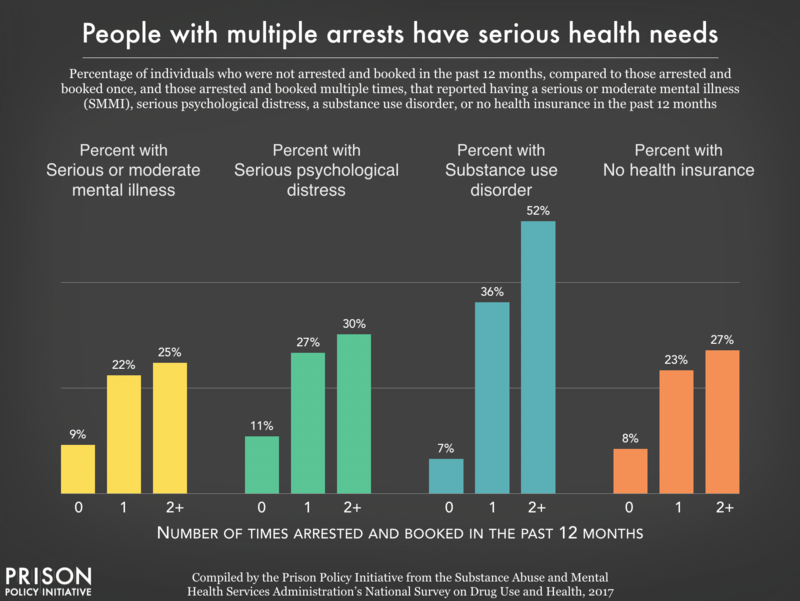

The report includes 31 visualizations of criminal justice data, exposing other long-standing truths about incarceration in the U.S.:

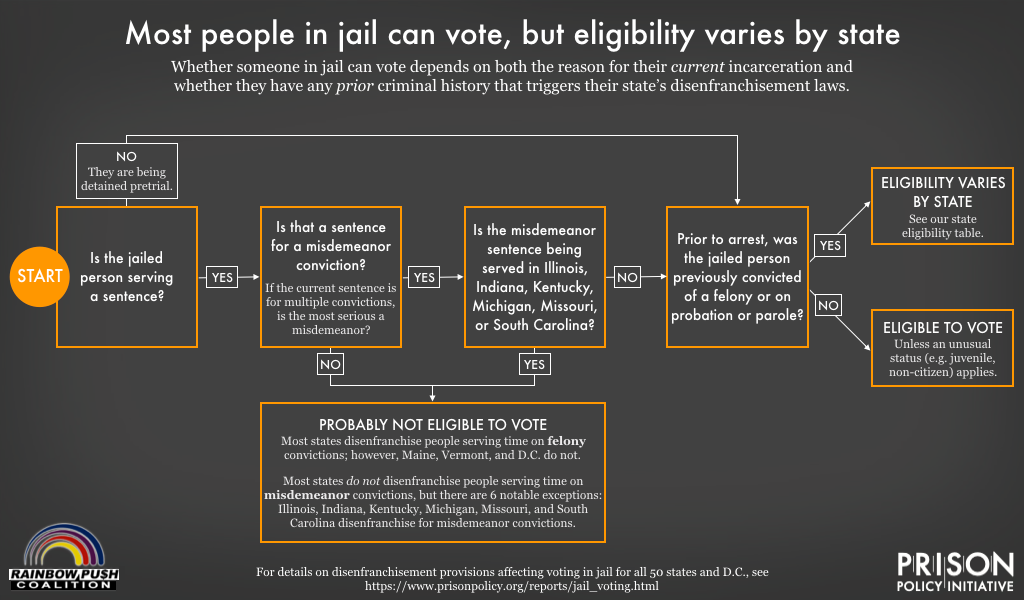

- The U.S. continues to lock up hundreds of thousands of people pretrial every day. A rise in the use of money bail over the last 40 years has driven an increase in pretrial populations.

- Black people are still overrepresented behind bars, making up about 38% of the prison and jail population.

- At least 113 million adults in the U.S. (or over 40%) have a family member who has been incarcerated, and 79 million people have a criminal record, revealing the ripple effects of locking up millions of people every day.

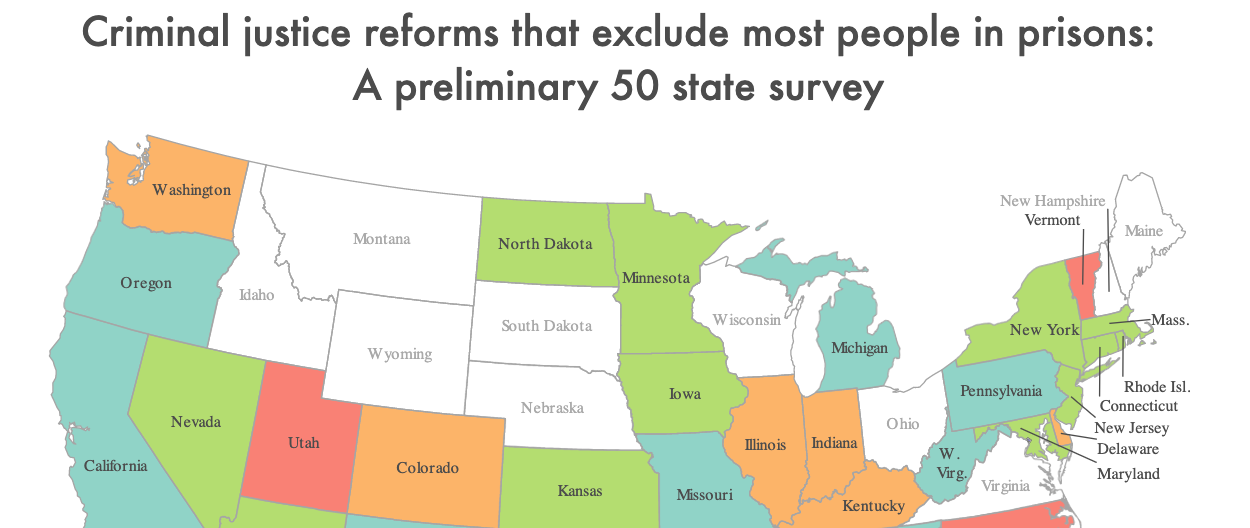

The report also tackles frequent misconceptions about mass incarceration related to prison labor, the war on drugs, private prisons, what victims of crime want, and community supervision.

“As the pandemic eases, and with incarceration rates as low as they’ve been in decades, elected leaders face a choice. They can take bold action to continue to reduce the number of people behind bars and invest in community responses that address the core causes of crime — poverty, addiction, and mental health struggles — or they can return to business as usual with incarceration rates stubbornly stuck at globally high rates and ballooning correctional budgets that burn through tax dollars without making communities safer and stronger,” said Sawyer. “The Whole Pie should serve as a call to action for government to finally end our nation’s failed experiment of mass incarceration.”

The Prison Policy Initiative traditionally releases a new version of its Whole Pie report annually however, COVID-related delays in the release of government-produced data prevented the organization from releasing a new version in 2021.

Read the full report, with detailed data visualizations at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2022.html.