What you should know about halfway houses

Halfway houses are a major feature of the criminal justice system, but very little data is ever published about them. We compiled a guide to understanding what they are, how they operate, and the rampant problems that characterize them.

by Roxanne Daniel and Wendy Sawyer, September 3, 2020

In May, an investigation by The Intercept revealed that the federal government is underreporting cases of COVID-19 in halfway houses. Not only is the Bureau of Prisons reporting fewer cases than county health officials; individuals in halfway houses who reached out to reporters described being told to keep their positive test results under wraps.

It shouldn’t take exhaustive investigative reporting to unearth the real number of COVID-19 cases in a halfway house. But historically, very little data about halfway houses has been available to the public, even though they are a major feature of the carceral system. Even basic statistics, such as the number of halfway houses in the country or the number of people living in them, are difficult to impossible to find.

Broadly speaking, there are two reasons for this obscurity: First, halfway houses are mostly privately operated and don’t report data the way public facilities are required to; second, the term “halfway house” is widely used to refer to vastly different types of facilities. So, we compiled the little information that does exist about halfway houses, explaining how various facilities commonly called “halfway houses” differ from each other, and the ways in which these criminal justice facilities often fail to meaningfully support formerly incarcerated people. We also explore why poor conditions and inadequate oversight in halfway houses have made them hotspots for COVID-19.

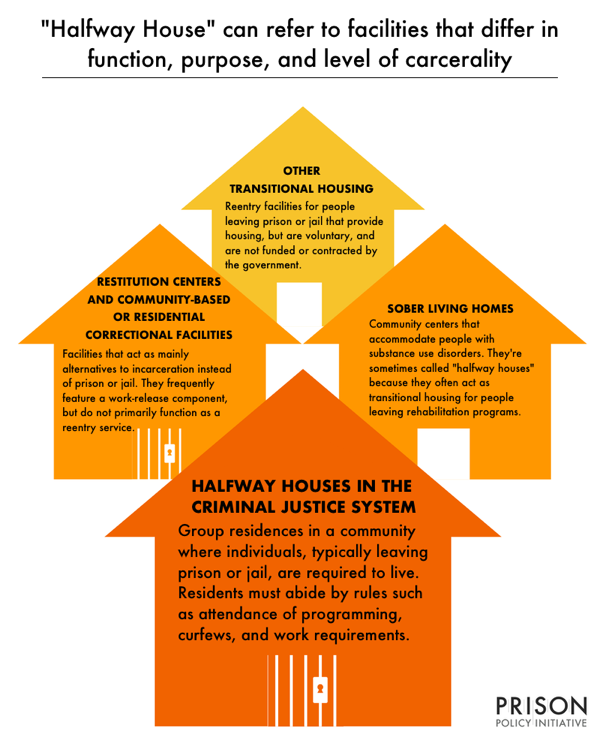

“Halfway house” is an umbrella term

The term “halfway house” can refer to a number of different types of facilities, but in this briefing we will only use halfway house to mean one thing: A residential facility where people leaving prison or jail (or, sometimes, completing a condition of probation) are required to live before being fully released into their communities. In these facilities, individuals live in a group environment under a set of rules and requirements, including attendance of programming, curfews, and maintenance of employment.

State corrections departments, probation/parole offices, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) often contract with nonprofits and private companies to run these facilities. These contracts are the primary means through which halfway houses receive funding.1

Federally contracted halfway houses are called Residential Reentry Centers (RRCs). State-licensed halfway houses can be referred to by a variety of terms, like Transitional Centers, Reentry Centers, Community Recovery Centers, etc. These facilities work with corrections departments to house individuals leaving incarceration, often as a condition of parole or other post-release supervision or housing plan.

“Halfway house” can also refer to a few other types of facilities, which will not be addressed in this briefing:

- Sober living homes, though sometimes housing formerly incarcerated people, do not serve the sole purpose of acting as a transitional space between incarceration and reentry. Sober living homes accomodate people with substance use disorders, and they’re sometimes called “halfway houses” because they often act as transitional housing for people leaving drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs.

- Restitution centers and community based/residential correctional facilities act as alternatives to traditional incarceration, instead of prison or jail, where individuals can go to serve their entire sentence. In restitution centers, people are expected to work and surrender their paychecks to be used for court-ordered fines, restitution fees, room and board, and other debts. Community based/residential correctional facilities frequently include a work-release component, but they function more as minimum-security prisons than reentry services.

- Some transitional housing providers for people leaving prison are voluntary for residents, and are not funded and contracted by the government. Susan Burton’s A New Way of Life Reentry Project, for example, provides safe housing and support for women leaving incarceration. Their services provide a potential model for the future of reentry programs that actually help residents rebuild their lives after the destructive experience of prison or jail.

Some facilities, like community-based correctional facilities, can serve dual functions that blur the lines of what facilities are and are not halfway houses. For instance, a community-based corrections facility might primarily house people who have been ordered to serve their full sentences at the facility, but also house some individuals who are preparing for release. We have included an appendix of the most recent list of adult state and federal correctional facilities that the Bureau of Justice Statistics calls “community-based correctional facilities” (those that allow at least 50% of the population to leave the facility). In our appendix table, we attempt to break down which of those 527 facilities fall under our “halfway houses in the criminal justice system” definition, and which facilities primarily serve other purposes.

Every year, tens of thousands spend time in halfway houses

The federal government currently maintains 154 active contracts with Residential Reentry Centers (RRCs) nationwide, and these facilities have a capacity of 9,778 residents. On any given day in 2018, RRCs held a nearly full population of 9,600 residents. While regular population reports are not available, 32,760 individuals spent time in federal RRCs in 2015, pointing to the frequent population turnover within these facilities.

Unfortunately, much less information exists about how many state-run or state-contracted halfway houses and halfway house residents there are. BJS data collected in 2012 indicates that there are 527 “community-based correctional facilities,” or facilities where 50% or more of the residents are regularly permitted to leave.2 These facilities held a one-day population of 45,143 males and 6,834 females, for a total of 51,977 individuals. However, as we will discuss later, these numbers include facilities that serve primarily or entirely as residential correctional facilities (where people serve their entire sentences). This ambiguity means that pinning down how many people are in halfway houses each day – and how many specifically state-funded halfway houses there are – is nearly impossible.

One reason that we know more about federal than state-level halfway houses has to do with the contracting process. The federal contract process is relatively standardized and transparent, while state contracting processes vary widely and publish little public-facing information, which makes understanding the rules governing people in state-contracted facilities much more difficult.

Halfway houses are carceral facilities

Contrary to the belief that halfway houses are supportive service providers, the majority of halfway houses are an extension of the carceral experience, complete with surveillance, onerous restrictions, and intense scrutiny.

For the most part, people go to halfway houses because it is a mandatory condition of their release from prison. Some people may also go to halfway houses without it being required, simply because the facility provides housing. Placement in Residential Reentry Centers (RRCs) post-incarceration can technically be declined by people slated for release, but doing so would require staying in prison instead.

In federal RRCs, staff are expected to supervise and monitor individuals in their facilities, maintaining close data-sharing relationships with law enforcement. Disciplinary procedure for violating rules can result in the loss of good conduct time credits, or being sent back to prison or jail, sometimes without a hearing.

Federal RRC residents3 are generally subject to two stages of confinement within the facility that lead to a final period of home confinement. First, they are restricted to the facility with the exception of work, religious activities, approved recreation, program requirements, or emergencies. A team of staff at the RRC determines whether an individual is “appropriate“4 to move to the second, less restrictive component of RRC residency. Even in this second “pre-release” stage, individuals must make a detailed itinerary every day, subject to RRC staff approval. Not only are residents’ schedules surveilled, their travel routes are subject to review as well.

Most states do not release comprehensive policy on their contracted halfway houses. From states like Minnesota, we are able to see that the carceral conditions in federal RRCs are often mirrored in the state system. Minnesota Department of Corrections (DOC) policy specifically calls for halfway houses to “[conduct] searches of residents, their belongings, and all areas of the facility to control contraband and locate missing or stolen property.” They also mandate that “staff shall maintain a system of accounting for the residents at all times,” that “methods used for control and discipline” are incorporated in written policy, and that there are “written procedures for the reporting of absconders.” The exact policies and procedures vary by facility, but all are expected to adhere to statewide guidelines; the conditions and intensity of carcerality will surely vary from halfway house to halfway house.

There’s far more that we don’t know: Lack of publicly available data makes it difficult to hold facilities accountable

Understanding halfway houses — including basic information like how many facilities there are and what conditions are like — is difficult for several reasons:

- No standard, transparent policies. There are few states that publicly release policies related to contracted halfway houses. In states like Minnesota, at least, there appear to be very loose guidelines for the maintenance of adequate conditions within these facilities. For example, beyond stating that buildings’ grounds must be “clean and in good repair,” the Minnesota DOC specifies no regular sanitation guidelines. Troublingly, beyond an on-site inspection to determine whether to issue a contract, there are no provisions for regular audits of halfway houses to affirm compliance with these policies.

- Privatization. The majority of halfway houses in the United States are run by private entities, both nonprofit and for-profit. For example, the for-profit GEO Group recently acquired CEC (Community Education Centers), which operates 30% of all halfway houses nationwide. Despite their large share of the industry, they release no publicly available data on their halfway house populations. The case is similar for other organizations that operate halfway houses.

- Poor federal data collection. As we noted earlier, the Bureau of Justice Statistics does periodically publish some basic data about halfway houses, but only in one collection (the Census of Adult State and Federal Correctional Facilities), which isn’t used for any of the agency’s regular reports about correctional facilities or populations. The BJS unhelpfully lumps reentry-focused halfway houses together with minimum security prisons and other kinds of community-based facilities in a broad category it calls “community-based correctional facilities,” making the data difficult to interpret. We can tell from the most recent data that, in 2012, there were 527 community-based facilities, but it remains unclear which facilities are which (we did our best to categorize them in the appendix ). It follows that the BJS does not publish disaggregated demographic data about the populations in these different types of facilities, making the sort of analysis we do about prisons and jails impossible. By contrast, the BJS releases detailed, publicly accessible data about prisons and jails, including population counts, demographic data, the time people spend behind bars, what services are offered in facilities, and more.

- Lack of oversight. The most comprehensive reporting on conditions in halfway houses are audits by oversight agencies from the federal government or state corrections departments. However, these audits are too few and far between. Since 2013, only 8 audits of federal RRCs have been released by the Office of the Inspector General. In the few publicly released reports from state-level agencies, we found a similar lack of frequency in reporting and other significant issues with oversight. In a 2011 audit from New Jersey, the state’s Office of Community Programs was found to be conducting far fewer site visits to halfway houses than policy required. The testing they performed to determine the extent and quality of services being provided was found thoroughly inadequate, and the Department of Corrections had no set standards to grade facilities on performance. Even when site visits were conducted, there was no way of authentically monitoring conditions at these facilities, since halfway house administrators were notified in advance of site visits and were able to pick and choose files to be reviewed.

These woeful inadequacies are indicative of a larger systemic failure of halfway house oversight that often results in deeply problematic conditions for residents. Too often, audits are only conducted after journalists report on the ways specific halfway houses are failing residents, rather than government correctional agencies doing proper oversight on their own.

Conditions in halfway houses often involve violence, abuse, and neglect

Since data remains sparse and oversight is unreliable, we have retrieved the bulk of information about conditions in halfway houses from the media and advocates. The voices of those who have spent time in halfway houses, and those who have worked in them, are key to understanding the reality of these facilities and the rampant problems that plague them.

Over 200 interviews with residents, workers, officials and others associated with halfway houses in New Jersey were conducted for a 2012 New York Times report. The interviewees described over 5,000 escapes since 2005, and cited drug use, gang activity and violence occurring in the facilities. The private company Community Education Centers (CEC, now GEO Group) operates the majority of New Jersey halfway houses. In a 2015 report on CEC (now GEO)’s troubled history, The Marshall Project confirmed the frequency of violence, drug use, and escapes in these facilities. While the role of halfway house administrators in creating unlivable, miserable conditions is unfortunately not the focus of these news reports (nor do they address the complex circumstances that foster drug use and violence), they do indicate that the facilities are inadequately serving their residents.

The largest CEC (now GEO) halfway house in Colorado was similarly subject to criticism when reporters found evidence of rampant drug use and gang violence, indicating the failure of the facility to provide a supportive reentry community. Subsequent audits identified a number of major staffing issues, including high turnover rates and misconduct. This pattern of inadequate staffing extends to CEC halfway houses in California, where a former facility director cited inadequate training and earnings barely above minimum wage. The clinical director of the California facility, responsible for resident health, did not possess a medical degree, or even a college degree.

Improper management and inadequate oversight of halfway houses also enables inequities in the reentry process. Journalists have revealed how, when individuals are required to have a halfway house lined up in order to be released on parole, they can encounter lengthy waitlists due to inadequate bed space, forcing them to remain in prison. In July, a Searchlight New Mexico investigation revealed that one halfway house was asking individuals to pay upfront rent in order to move to the “front of the line.” 89 people who were approved for release remained in prison due to their inability to pay to get off of the halfway house waitlist.

These media reports are too often the only way we are able to retrieve public information about the internal conditions of halfway houses. From the lived experiences of those who have resided in halfway houses, it is clear that egregious conditions in halfway houses are common.

Poor conditions and bad incentives make halfway houses hotspots for COVID-19

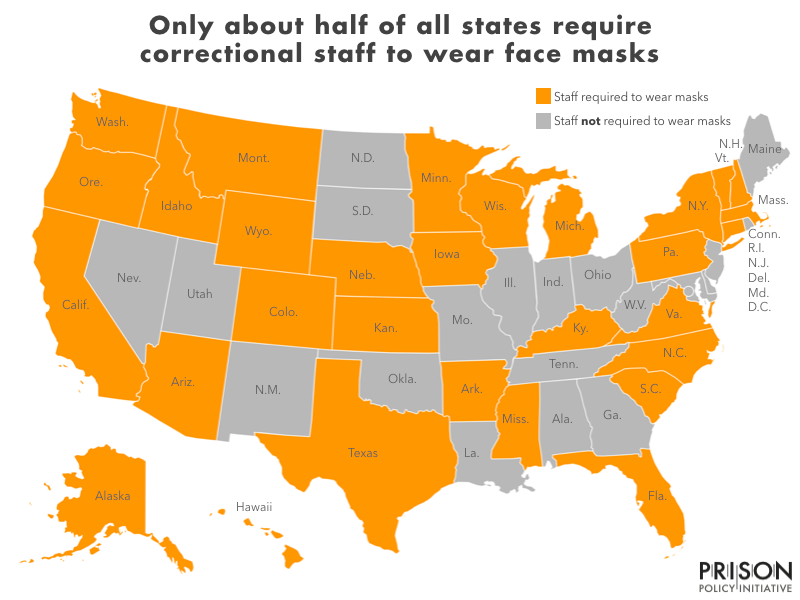

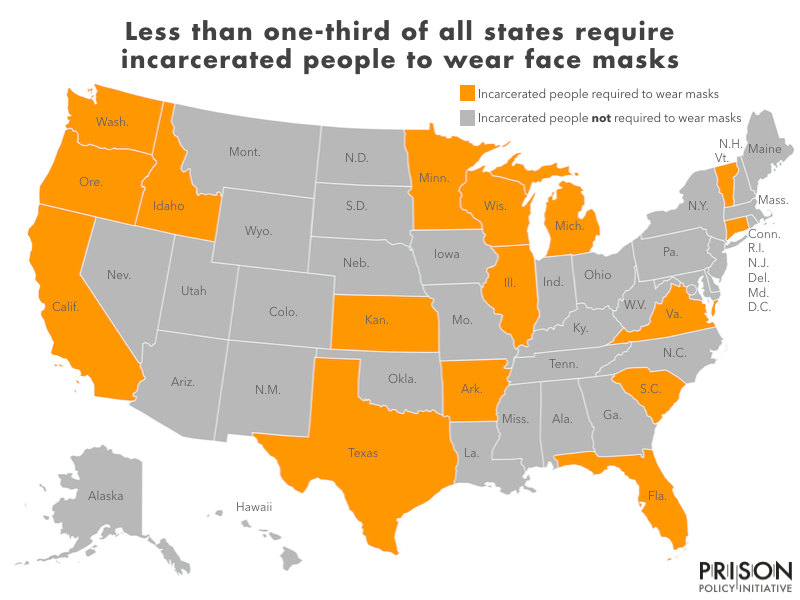

Now, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more important that the public focus on the jail-like conditions of halfway houses which put vulnerable populations at risk. As of August 18, federal Residential Reentry Centers (RRCs) had 122 active cases, and 9 deaths, of coronavirus among halfway house residents nationwide. However, recent investigative reports suggest that the real numbers are even higher, as the BOP continues to underreport cases in RRCs and state-level data is nearly non-existent. For instance, The Intercept noted that the GEO Grossman Center in Leavenworth, Kansas had 67 cases (including staff) in May, as reported by the country health officials; yet the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) currently only reports a history of 29 cases of coronavirus in the Center, with no history of cases among staff.

Cases of COVID-19 are uniquely dangerous in halfway houses due to the work release component of many facilities. When some halfway houses locked down to prevent community spread, people who had been employed in high-density work environments, and/or travelled to work by public transportation, were confined in tight quarters with other residents for an extended period, risking disease spread. Now, as individuals return to work, halfway houses are positioned to be vectors of the virus, as the lack of social distancing and adequate living spaces is exacerbated by the frequency with which individuals have contact with the greater community.

Residents of halfway houses have described deeply inadequate sanitation and disease prevention on top of the lack of social distancing. In the now-defunct Hope Village in Washington, D.C., residents reported packed dining halls, makeshift PPE, and restricted access to cleaning products and sanitation supplies. In a Facebook video, a resident described “6 to 8 people” leaving Hope Village daily in an ambulance.

What’s more, halfway houses have a financial incentive to maintain full occupancy due to the conditions of contracts. While the federal Bureau of Prisons has prioritized home confinement as a component of the CARES Act, and has urged federal RRCs to facilitate the process of home confinement releases despite the financial risk, state systems have been more ambiguous about their recommendations for halfway houses. Since states have overwhelmingly failed to protect incarcerated people in jails and prisons, the outlook for halfway houses is bleak.

Conclusion

The gruesome portrayal of halfway houses in the media can often be the catalyst for formal audits of these facilities. But it should be noted that regular monitoring, auditing, and data reporting should be the norm in the first place. Halfway houses are just as much a part of someone’s prison sentence as incarceration itself, but they are subject to much less scrutiny than prisons and jails. This lack of guidelines and oversight has ensured that people in halfway houses are not being aided in safely and effectively rebuilding their lives after serving time in jails and prisons. It’s past time to start implementing oversight measures and extensive reforms that keep residents safe and help the halfway house experience feel more like reentry – and less like an extension of the carceral experience.

Footnotes

- In 2011, the private company Community Education Centers (CEC) received $71 million in contracts from state and county agencies.

- This number includes federal RRCs.

- In the Census, residents of halfway houses are counted at the halfway house, not at their pre-incarceration home. Halfway houses are supposed to be located in the communities in which residents will return to post-release, but this might not always be the case. We refer to individuals in halfway houses as “residents” as a working term to indicate halfway house placement, but they are still subject to prison gerrymandering.

- Residential Reentry Center, Statement of Work (SOW) April 2017. P. 54