The parallel epidemics of incarceration & HIV in the Deep South

HIV disproportionately impacts communities that are already marginalized by poverty, inadequate resources, discrimination — and mass incarceration.

by Emily Widra, September 8, 2017

In a New York Times Magazine article published in June 2017, journalist Linda Villarosa highlighted the “hidden HIV epidemic” among Black gay and bisexual men in the Deep South. The overall decline of HIV rates in the US may give some people a premature sense of victory; this progress obscures the fact that HIV remains a significant problem for a disproportionate number of Black gay and bisexual men in this country, as Villarosa points out:

“Swaziland, a tiny African nation, has the world’s highest rate of H.I.V., at 28.8 percent of the population. If gay and bisexual African-American men made up a country, its rate would surpass that of this impoverished African nation — and all other nations.”

Villarosa mentions the systemic issues impacting HIV rates among southern Black communities, including the “crippled medical infrastructure,” the limited domestic funding and resources dedicated to HIV/AIDS, and the movement of the HIV epidemic from cities like New York and San Francisco to smaller cities with larger Black populations in the Deep South. Along these lines, Dr. Mark Dybul — an infectious diseases researcher and professor — describes HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis as “discriminatory” diseases because they disproportionately impact communities that are already marginalized by poverty, inadequate resources, and discrimination. Villarosa also briefly touches on the history of incarceration of a few of the men she interviewed, but the intersection of HIV, race, and incarceration deserves further investigation, especially considering the high rates of incarceration in the South.

There is little information available about LGBT people of color behind bars, and even less data on the rates of HIV and incarceration among men who have sex with men. In the public health literature that does exist on HIV, the category of men who have sex with men, or MSM, is applied broadly and inconsistently to self-identified gay and bisexual men, men with a lifetime history of male-to-male sexual contact, and/or men who self-report male-to-male sexual contact in the past 6 months, depending on the particular study. The lack of consistency and clarity when we talk about this population only makes it harder to address these issues. As Villarosa puts it, “too many black gay and bisexual men [are] falling through a series of safety nets.”

The existing studies begin to fill in the gaps in literature, but there is more work to be done to understand how the interactions of high rates of HIV and our criminal justice system disproportionately impact Black gay and bisexual men and Black MSM. Recent research suggests an overlap between HIV and incarceration:

- People at risk for incarceration are more likely than others to be at high risk for HIV infection. These risk factors include a history of drug use, low socioeconomic status, high prevalence of STIs, mental illnesses, and history of assault and/or abuse.

- An estimated 25% of Americans living with an HIV infection were incarcerated during 2008.

This is much worse for Black men, like the men that Villarosa interviewed. The compounding effects of HIV, incarceration, and discrimination intersect in the lives of Black gay and bisexual men and Black MSM.

- First, it is clear that the HIV epidemic among Black MSM that Villarosa points out is real. The CDC reported that “if current HIV diagnoses rates persist about 1 in 2 Black men who have sex with men (MSM) will be diagnosed with HIV during their lifetime.”

- And there are a lot of Black MSM in prison. Using data from the National Inmate Survey, 2011-2012, researchers found that 34.3% of Black men in prison were MSM, while only 8.9% of the total US population of MSM is Black. (The total Black MSM population is unknown, but would be useful for measuring overrepresentation.)

- These men who are at a heightened risk of HIV are especially vulnerable behind bars, where condoms are typically unavailable. (Male-to-male sexual contact contributes to over 70% of HIV diagnoses among Black men.)

- Finally, it looks like Black MSM are at high risk for both HIV diagnosis and incarceration. There is limited data on how much of the US Black MSM population has a history of incarceration, but one study found that 58.7% of a sample of 1,385 Black MSM self-reported a history of incarceration.

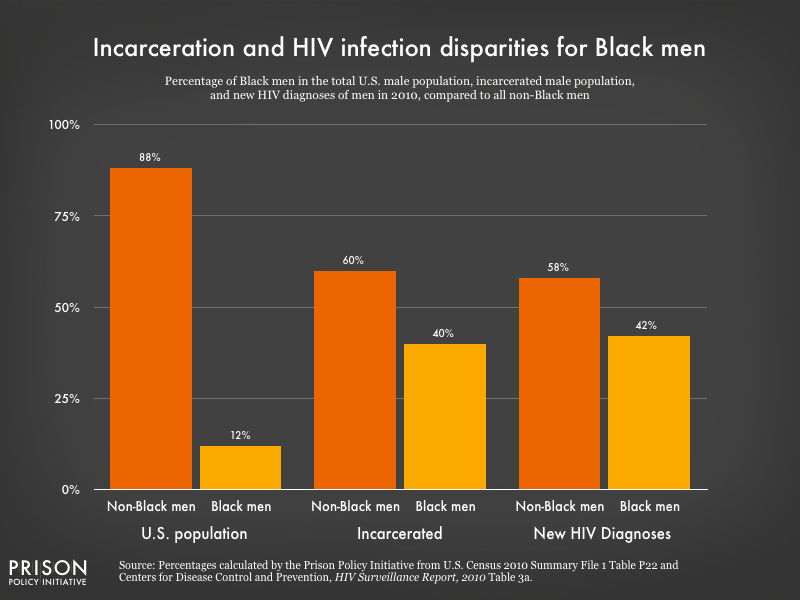

The bottom line is Black men are overrepresented in the number of people with HIV and in the number of people behind bars. Although Black men made up only 12% of the US male population at the time of the last Census, they accounted for over 40% of all incarcerated men and 42% of all newly reported HIV infections of men in the US.

The co-occurrence of high rates of HIV diagnoses and high rates of incarceration among Black men does not necessarily imply a causal relationship, but they work together to specifically burden the lives of Black gay and bisexual men — particularly in the South, where those rates are especially high. In a previous post, I wrote about the overrepresentation of Black women among new HIV infections, which some researchers have attributed to the high rates of incarceration of Black men.

The co-occurrence of high rates of HIV diagnoses and high rates of incarceration among Black men does not necessarily imply a causal relationship, but they work together to specifically burden the lives of Black gay and bisexual men — particularly in the South, where those rates are especially high. In a previous post, I wrote about the overrepresentation of Black women among new HIV infections, which some researchers have attributed to the high rates of incarceration of Black men.

These findings point to an alarming convergence of the population most burdened by HIV/AIDS and the population most disproportionately affected by mass incarceration. This intersection clearly warrants more attention, so I’m frustrated by the small number of studies dedicated to unravelling the connection between HIV, incarceration, and race.

The first analysis of incarceration history among Black MSM was conducted in 2014 and found evidence that there is a heightened lifetime risk of incarceration among Black MSM. Now, we need more nationally representative and rigorous studies to corroborate these findings. Villarosa argues that by incorporating the gay and bisexual Black men (and we would add, Black men who have experienced incarceration) into the literature and the larger understanding of HIV, we can improve outreach and preventative measures, increase the voice and standing of people of color in HIV/AIDS advocacy, and empower communities to demand change.

As Dr. Dybul states, “HIV is itself discriminatory, it preys on people who are left behind or marginalized by society.” Villarosa’s article highlights the stigma and marginalization of Black gay and bisexual men in the South, but it is important to note that this oppression is layered and systemic: Black MSM and Black men with HIV are also incarcerated at high rates, which only adds to the challenges they face when they return home to their communities.