BJS victimization figures show slight decline in violent crime

While recent BJS figures showed an increase in total incarcerated population, crime figures show a decrease in violent crime.

by Bernadette Rabuy, September 18, 2014

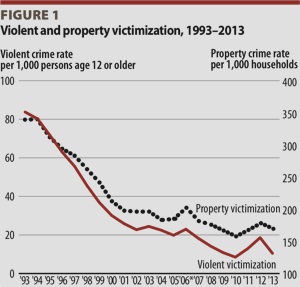

This morning, two days after releasing, Prisoners in 2013 the Bureau of Justice Statistics released, Criminal Victimization, 2013. Once again, the BJS released criminal justice figures that reverse the trend of the past few years. After two years of slight increases in the nation’s violent crime rate, the violent crime rate declined slightly from 26.1 victimizations per 1,000 persons in 2012 to 23.2 per 1,000 in 2013. (The crime rate is now re-approaching the record low it hit in 2010 and is far lower than it was two decades ago.)

This morning, two days after releasing, Prisoners in 2013 the Bureau of Justice Statistics released, Criminal Victimization, 2013. Once again, the BJS released criminal justice figures that reverse the trend of the past few years. After two years of slight increases in the nation’s violent crime rate, the violent crime rate declined slightly from 26.1 victimizations per 1,000 persons in 2012 to 23.2 per 1,000 in 2013. (The crime rate is now re-approaching the record low it hit in 2010 and is far lower than it was two decades ago.)

While there were no statistically significant changes in most other types of crime, the slight drop in the crime rate was mostly the result of a decline in simple assault, which is violence that doesn’t include a weapon or serious injury. The decline in simple assault accounted for about 80% of the change in total violence. The rate of property crime also fell from 155.8 victimizations per 1,000 households in 2012 to 131.4 per 1,000 in 2013.

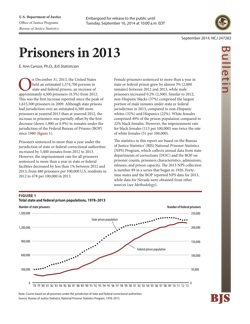

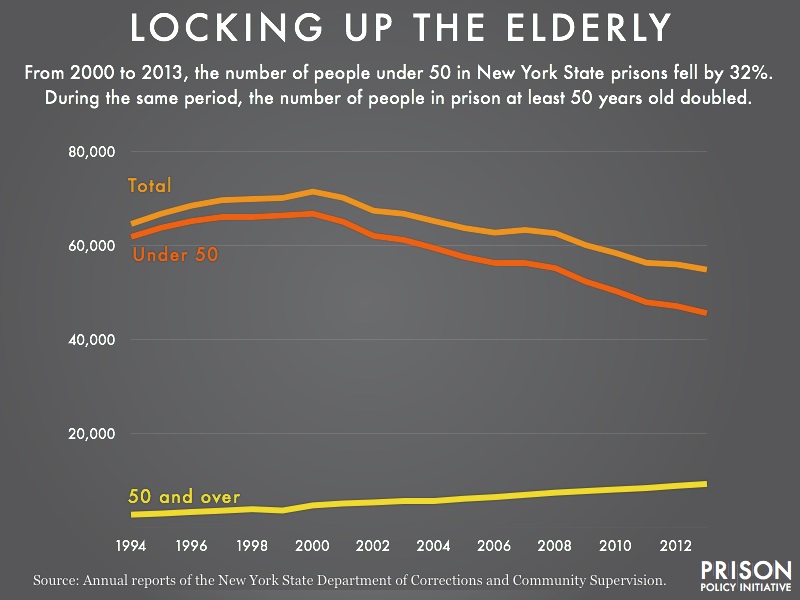

These figures led to an interesting discussion on Twitter among those of us who have been closely following BJS’ recent releases. In BJS’ Prisoners in 2013, we learned that the state and federal prison population increased slightly from 2012 to 2013, the first overall increase since 2009. Although these figures may point out that it is too early to be celebrating the end of mass incarceration, it is safe to say that the state and federal prison population has held fairly steady compared to the rapid rise of earlier decades.

@PrisonPolicy Many will suggest a direct correlation but that would be spurious.

— Side-Eye (Harder) (@prisonculture) September 18, 2014

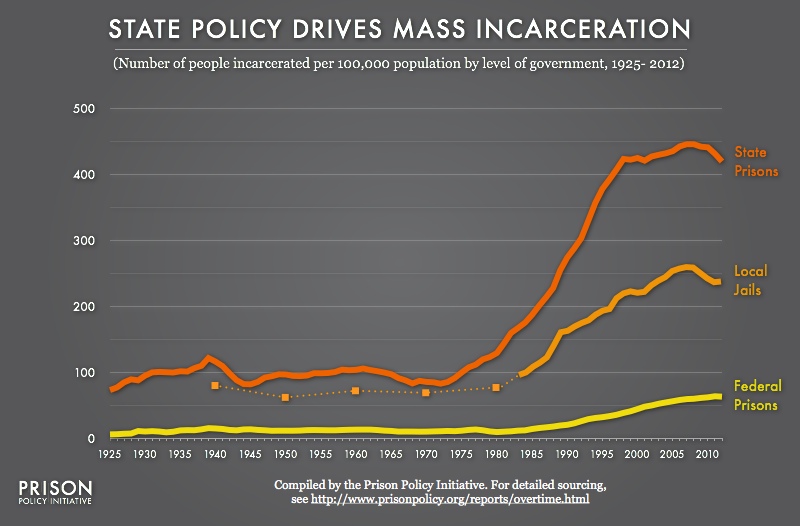

@prisonculture State policy drives mass incarceration http://t.co/ewqe5ClQsI pic.twitter.com/6gJ45iArsu

— Prison Policy Init. (@PrisonPolicy) September 18, 2014

As Mariame Kaba of Project NIA tweeted, it is extremely difficult to draw a relationship between the imprisonment rate and the crime rate. In Ted Gest’s analysis of Criminal Victimization, 2013, he wrote for The Crime Report,

Critics question why more people should be behind bars while crime is dropping. The basic answer is that there is not necessarily a connection between the two sets of numbers.

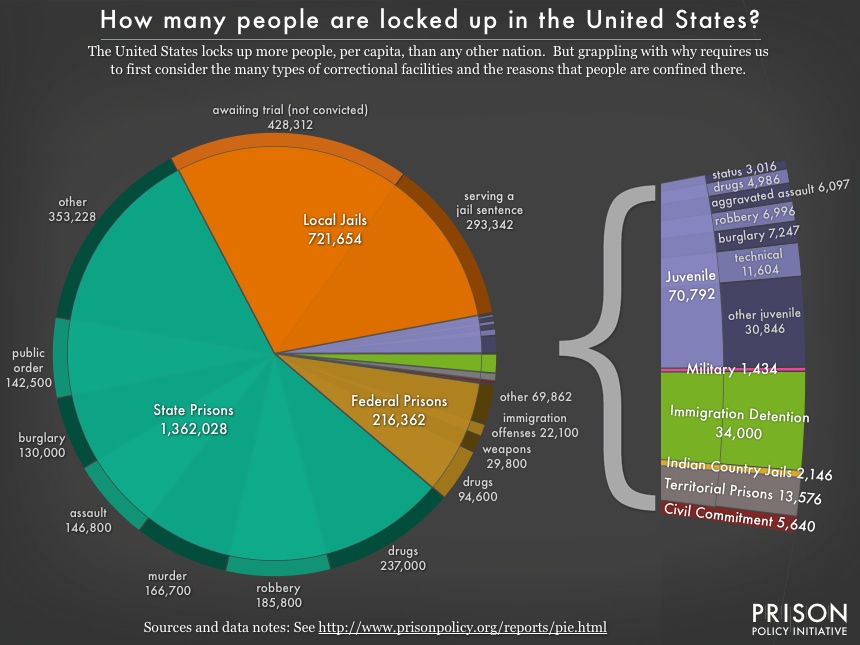

The Pew Public Safety Performance Project recently released a data visualization trying to illustrate the complex link between prison and crime. While the BJS’ releases looked at the change in incarceration and crime over the last year, the Pew Public Safety Performance Project recently analyzed state incarceration and crime rates from over the last two decades. They found that the five states with the largest decreases in their imprisonment rates were able to reduce their crime rates. Overall, there isn’t a clear-cut trend, but one thing is clear: locking more people up doesn’t necessarily lead to less crime.

The visualization is a reminder of what we found in our report, Tracking State Prison Growth in 50 States: State policy drives mass incarceration. States with high rates of incarceration have very little to show for it.