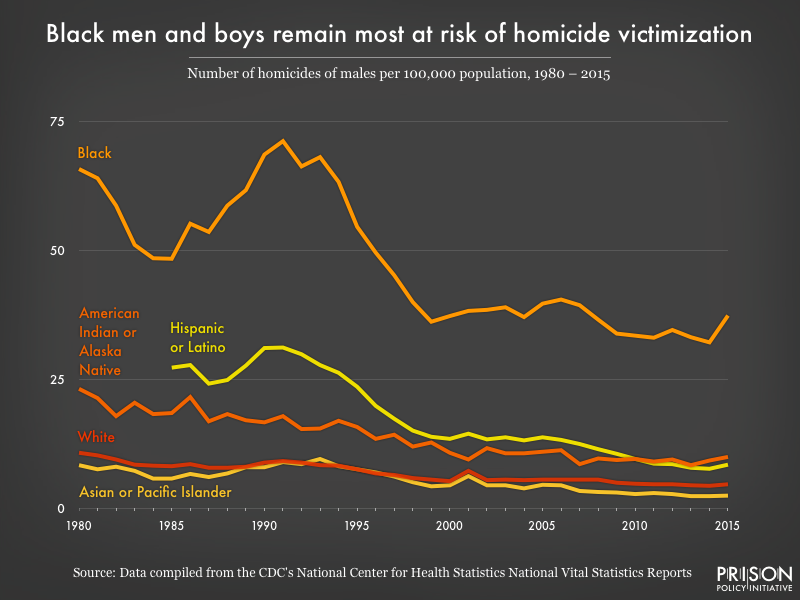

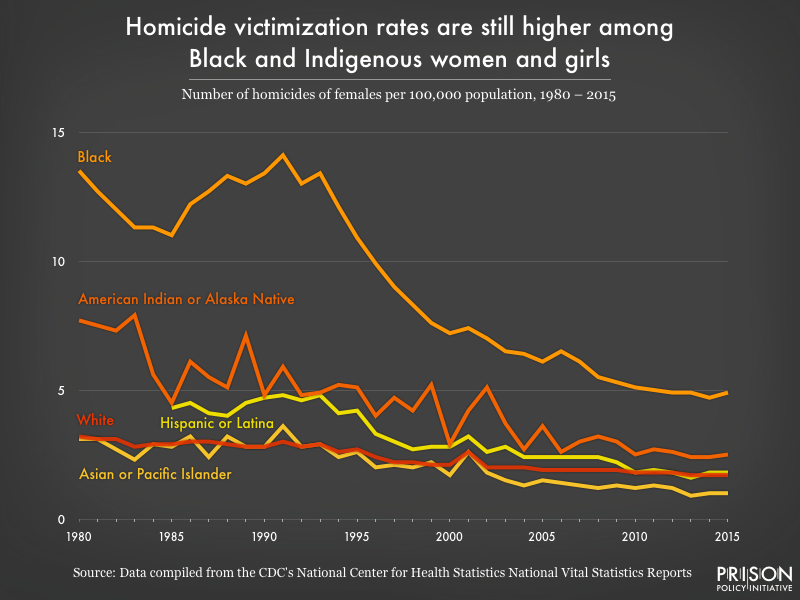

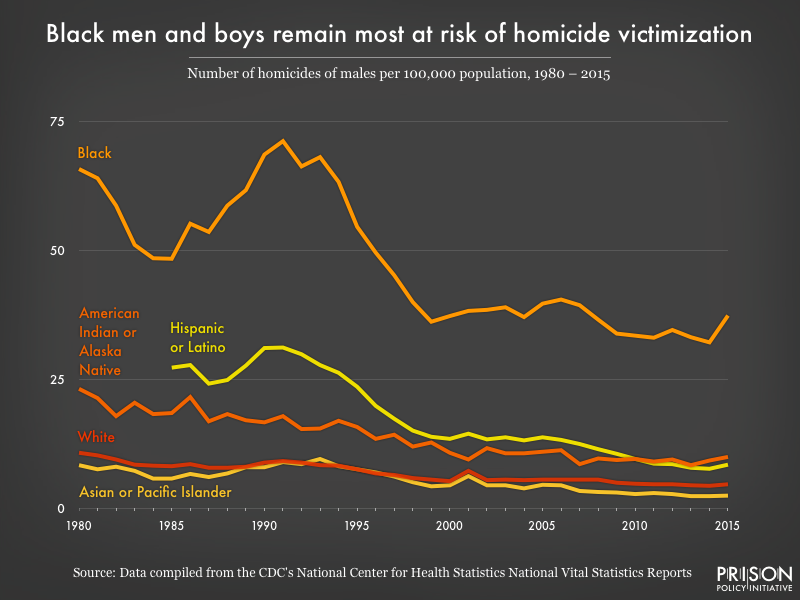

Homicide victimization rates for Black men, Black women and Indigenous women are consistently higher than for other racial and ethnic groups.

by Emily Widra,

May 3, 2018

I wanted to compare homicide victimization across racial, ethnic, and gender groups over time, since this data is deceptively difficult to find in one place.

In the process, I found that the murder victimization rate for Black men is consistently higher than the rates for men of all other racial and ethnic groups have ever been:

Despite a drop in overall murder rates, the racial disparities in male murder victimization rates have persisted.

Despite a drop in overall murder rates, the racial disparities in male murder victimization rates have persisted.

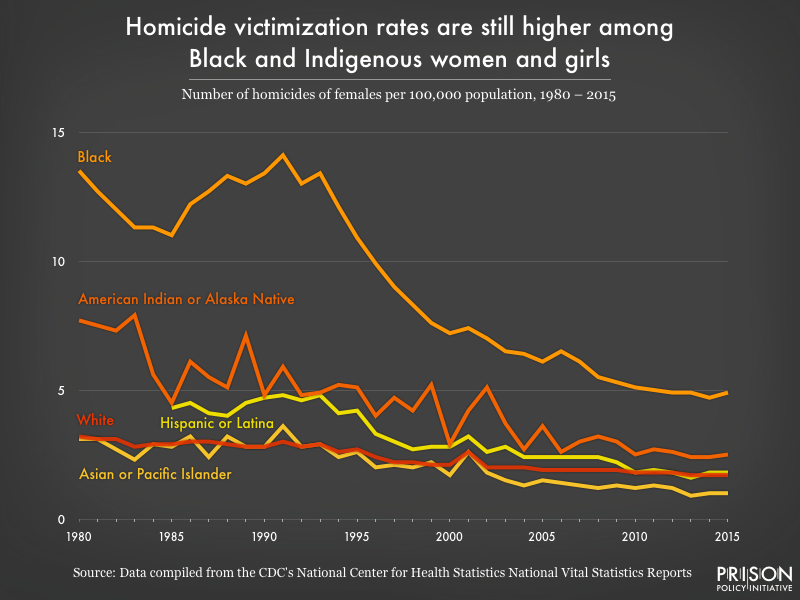

Controlling for gender reveals more complexity. For example, the rate of homicide of Indigenous women is higher than the rate of homicide for Hispanic and Latina women, whereas the opposite is true for their male counterparts:

Overall, Black, Hispanic or Latinx, and American Indian and Alaskan Native people are murdered at much higher rates than their white or Asian and Pacific Islander counterparts.

Overall, Black, Hispanic or Latinx, and American Indian and Alaskan Native people are murdered at much higher rates than their white or Asian and Pacific Islander counterparts.

Overall murder rates have been declining since 1980, when the total rate for murder and non-negligent manslaughter was 10.2 per 100,000 people. But the disproportionately high rate at which Black Americans are murdered should still concern lawmakers, reporters, and the public.

Unfortunately, conversations about about this problem often fall back on the assumption that violence in Black communities has cultural — or even biological — roots. But these assumptions aren’t supported by data.

For instance, Krivo and Peterson’s analysis of crime data in Columbus, Ohio shows that economic disadvantage, not race, is the strongest predictor of violence in a particular neighborhood. “In fact,” they conclude, “violent crime rates for extremely disadvantaged white neighborhoods are more similar to rates for extremely disadvantaged black areas than to rates for other types of white neighborhoods.”

Studies like these suggest that racial disparities in murder rates stem from a variety of structural causes, most notably economic inequality. (To dig deeper, see Krivo and Peterson’s study controlling for neighborhood disadvantage, as well as the Violence Policy Center’s recent study of Black homicide victimization.)

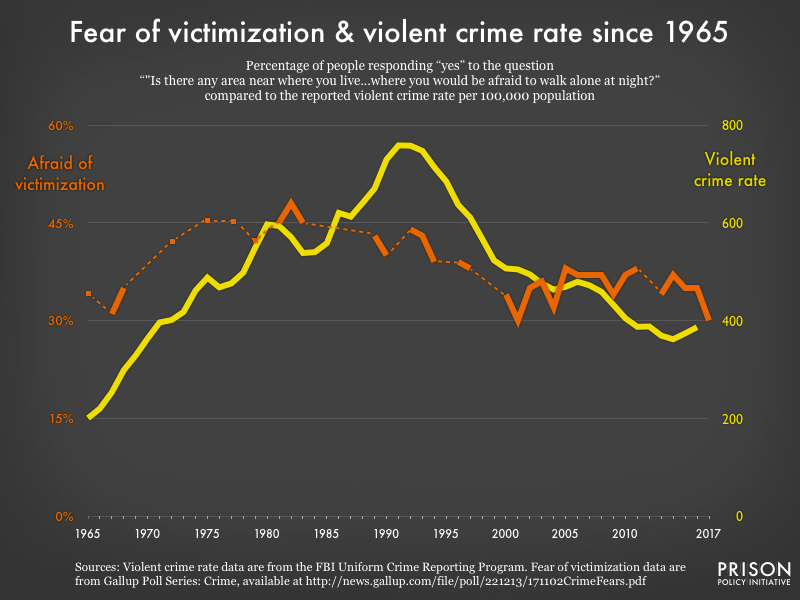

Comparing violent crime rates to public opinion data shows that there's a long-standing disconnect between perception and reality.

by Emily Widra,

May 3, 2018

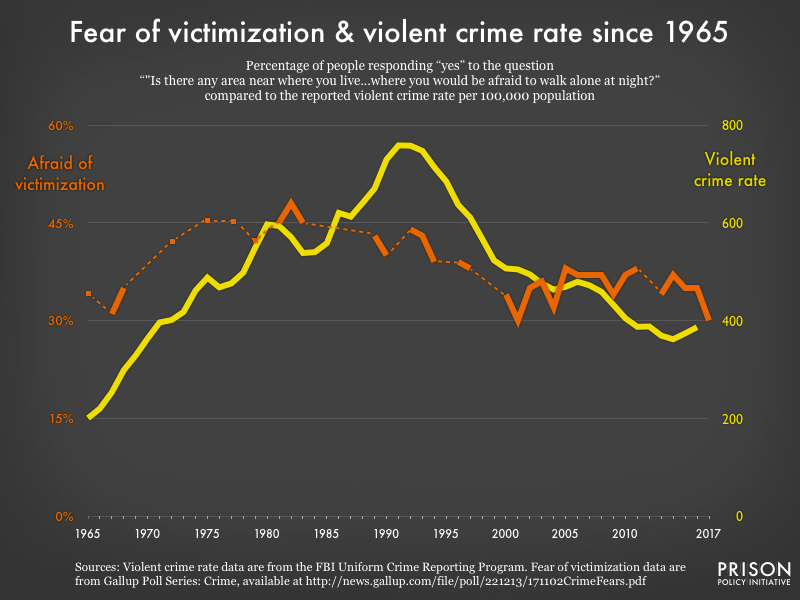

I updated a graph from our 2003 book The Prison Index to answer the question: How closely does Americans’ fear of violent crime reflect the actual violent crime rate?

The answer: Hardly at all.

Beginning in 1965, Gallup began asking Americans if there was “any area near where you live…where you would be afraid to walk alone at night?” Over time, these poll results show a tenuous relationship, at best, between the violent crime rate and the number of people who report being afraid:

The violent crime rate (yellow) peaked in 1991. The fear of crime (orange) peaked nine years earlier and was already declining when the violent crime rate was approaching its peak.

The violent crime rate (yellow) peaked in 1991. The fear of crime (orange) peaked nine years earlier and was already declining when the violent crime rate was approaching its peak.

Of course, this data isn’t sensitive to regional and economic variations in crime across the country. And people who aren’t afraid of being attacked might be afraid to walk around at night for other reasons.

But it’s interesting to explore the discrepancy between perception and reality. From the early 1980s to the early 1990s, as violent crime reached historic heights, Americans’ fear of victimization fell.

This isn’t to say that Americans are grossly out of touch. But it should remind elected officials and media that the last place to look for evidence of a crime wave is in public opinion polls.

New data and analysis from BJS and Columbia University this week show the number of people on probation or parole is edging in the right direction, but states continue to set people up to fail with long supervision terms, onerous restrictions, and constant scrutiny.

by Wendy Sawyer and Wanda Bertram,

April 26, 2018

Meek Mill was released on bail from a Pennsylvania prison this week, but like many of the 4.5 million people in the U.S. on probation and parole, he still doesn’t feel free. The Philadelphia rapper, whose probation violations landed him back in prison years after serving his original sentence, has brought attention to the problem of community supervision cycling people back into prisons and jails.

Two reports – also published this week – shed new light on the system that has “stalked” Meek Mill for close to a decade. In his analysis of community corrections in Pennsylvania, Columbia Professor Vincent Schiraldi shows how the state’s long probation and parole terms give it one of the highest rates of community supervision in the country. Those sentencing practices, along with excessive use of pretrial detention for technical violations, make Pennsylvania a perfect example of how probation and parole contribute to unnecessary incarceration.

Probation and parole widen the net of incarceration by keeping people under onerous restrictions and monitoring instead of focusing squarely on reentry assistance. In states like Pennsylvania, the consequences are clear: Fully half of Philadelphia’s jail beds, along with one-third of Pennsylvania’s prison beds, are occupied by people charged with parole and probation violations. Incarcerated at great personal cost and public expense, these people are locked up for things as minor as failed drug tests and leaving the county without permission (as Mill was).

Restrictive and long-term supervision doesn’t pay off in enhanced public safety. Instead, as Prof. Schiraldi points out, supervision of individuals at low risk of reoffending “actually increases their likelihood of rearrest.” Meanwhile, supervision stretches resources that could be more effectively directed at higher-risk cases.

So it’s welcome news that probation populations are down nationwide, according to a second report, this one from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In its annual report on probation and parole, BJS reports that the number of people under any form of community supervision fell by 1.1% in 2016. (The number of people on parole actually increased slightly, meaning that the entire decrease is due to a drop in probation.)

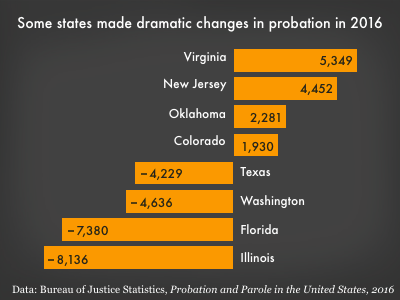

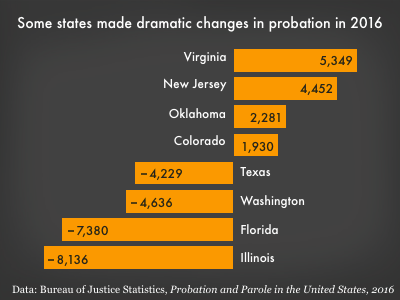

Change in the total probation population in select states, from yearend 2015 to yearend 2016.

Surprisingly, four states appear to account for half the decrease in probation: Illinois, Florida, Washington, and Texas collectively cut over 24,000 people from probation supervision, more than all other states combined.

But it’s important not to read this data too optimistically. Several states added to their probation populations: Virginia added 5,300 (10%) more people to probation, New Jersey added 4,500, Oklahoma added 2,300 (7%), and Colorado and Arkansas each added 1,900. (12 other states added smaller numbers to probation.)

The White House has declared April National Second Chance Month, a time to focus on “opportunities for people with criminal records to earn an honest second chance.” Meanwhile, though the number of people on probation and parole is edging in the right direction, states continue to set up millions of people to fail with needlessly long supervision terms, numerous restrictions, and constant scrutiny. With such a high human cost, it’s critical that policymakers look for alternatives to incarceration that provide genuine assistance, rather than unnecessarily expanding the criminal justice system’s reach.

Our January report showed how incarcerated women are being left behind, but to identify specific areas for improvement, state-level research is needed.

by Wanda Bertram,

April 11, 2018

In our January report The Gender Divide, we identified more than 30 states where recent criminal justice reforms have had little to no impact on women. The result? Nationally, women’s incarceration rates still hover near record highs, even as men’s rates are going down.

But why exactly are women being left behind, and what can states do to change course? Our report addressed these questions broadly, but to identify problematic policies or specific areas of need, drilling down to the local level is necessary. So I teamed up with Sasha Feldstein, a member of our Young Professionals’ Network, to compile a list of state studies worth reading in full.

Here are some of the insights from these important studies:

- “The increase in women becoming involved in the criminal justice system can be traced to changes in state and federal drug policies that included prosecution of both users and distributors. Law enforcement practices of targeting users and low-level drug offenders led to an increase in women being charged with drug offenses.”

– Nebraska ACLU, Let Down and Locked Up: Nebraska Women in Prison

- “Resource-based bail systems are particularly problematic for women, as poverty is a particularly significant factor for justice-system-involved women. A higher percentage of women reported incomes of less than $600 per month immediately prior to their incarceration than their male counterparts, with two-thirds of these women earning minimum wage in entry-level positions.”

– Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, A Growing Problem: The Surge of Women into Texas’s Criminal Justice System

- “The number of women sentenced for felony property crimes doubled from 2000 to 2011. As a result of Oregon’s creation of harsher penalties for property crimes such as ID theft, more women are being incarcerated for longer periods, including for behaviors that historically would not have been punished with imprisonment.”

– Oregon Justice Resource Center, Women in Prison in Oregon

- “Data reveals a higher prevalence of discipline among all incarcerated women than men at prisons statewide…The number of disciplinary tickets is almost double for the women’s population than for men. Disparities were prevalent for ‘minor insolence’ infractions, where the average number of disciplinary tickets issued to the women’s prison population was almost five times higher than those issued to men.”

– Women’s Justice Institute and Illinois Department of Corrections, The Gender Informed Practice Assessment: Summary of Findings and Recommendations

- “Just under 70 percent of incarcerated women in June of 2016 had an actively managed or serious mental illness, compared to 44 percent of incarcerated men…the Task Force recognizes the need for and recommends additional and appropriate funding dedicated to the expansion of community supervision as well as mental health and addiction treatment for offenders.”

– Oklahoma Justice Reform Task Force, Final Report

- “Changes in arrest practice and policy in situations of domestic violence could potentially divert a significant number of women charged with assault-related offenses from the system…[Crisis intervention training] should be expanded to reach all officers and incorporate gender-responsive, trauma-informed practices to prevent encounters from escalating.”

– John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Women InJustice: Gender and the Pathway to Jail in New York City

- “Native American women comprise 21% of the inmate population. Though individuals of non-white races are overrepresented in Minnesota’s prison population, the incarceration of Native Americans is dramatically disproportionate…and the proportion of Native American women in the prison population outpaces that of men.”

– Robina Institute (at the University of Minnesota), Women in Prison: A Small Population Requiring Unique Policy Solutions

- “Incarcerated women are often parents, and the separation from children often creates financial and emotional hardship for families. All three of the state’s prison facilities are located in the southern part of the state and northern Nevada families may face difficulties in traveling to visit their incarcerated female family members. Many states have adopted policies that take children and families into consideration when choosing a prison assignment for a parent.”

– Guinn Center for Policy Priorities, New Study Sheds Light on Challenges for Women Behind Bars

The United States holds nearly 30% of the world’s incarcerated women. Most shouldn’t be there at all, or could be better served through alternatives to incarceration, as these reports suggest. Developing ways to help disadvantaged women rather than incarcerating them should be an urgent priority in every state.

A new court settlement illustrates the pervasiveness of criminal record discrimination in the United States.

by Lucius Couloute,

April 11, 2018

According to documents filed last week, The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF) has reached a settlement with the Target Corporation in a discriminatory hiring lawsuit. From 2008 to 2016 Target denied employment to over 41,000 Black and Latinx job applicants simply because they had a criminal record.

If approved by the court, Target will be required to reform its hiring procedures and to compensate the tens of thousands of people who were subject to criminal record discrimination.

The settlement builds from updated guidelines published by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in 2012 establishing that the exclusion of people with criminal records can violate the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (which prohibits employment discrimination on the basis of race, religion, sex, or national origin). Basically, if employers like Target are using criminal records to automatically disqualify applicants, it is likely that they are disproportionately disqualifying applicants of color and violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Those covered in the settlement would qualify for either an entry-level job at Target, or monetary compensation up to $1,000 (if, for example, they are retired or cannot work due to a disability). The settlement also requires Target to contribute $600,000 to reentry organizations that support individuals with criminal records, and to create new guidelines for the use of criminal records in making hiring decisions.

The settlement won’t change the economic fate of everyone with a criminal record, but it does send a clear message to employers across the country: discrimination could cost you.

And it should.

The Massachusetts conference committee between the House and Senate recently reached an agreement on criminal justice reform which includes an important measure that will protect in-person jail visits.

by Lucius Couloute,

March 26, 2018

Last week, after many months of effort on the part of grassroots organizations and lawmakers, the Massachusetts conference committee between the House and Senate reached an agreement on criminal justice reform – including a measure that will protect in-person visits for incarcerated people and their families.

The bill is quite extensive, but the language around visitation reads:

A correctional institution, jail or house of correction shall not: (i) prohibit, eliminate or unreasonably limit in-person visitation of inmates; or (ii) coerce, compel or otherwise pressure an inmate to forego or limit in-person visitation. For the purposes of this section, to unreasonably limit in-person visitation of inmates shall include, but not be limited to, providing an eligible inmate fewer than 2 opportunities for in-person visitation during any 7-day period.

A correctional institution, jail or house of correction may use video or other types of electronic devices for inmate communication with visitors; provided, that such communications shall be in addition to and shall not replace in-person visitation, as prescribed in this section.

Nothing in this section shall prohibit the temporary suspension of visitation privileges for good cause including, but not limited to, misbehavior or during a bonafide emergency.

The Senate and the House will get opportunities to vote on the bill before it finds its way to Gov. Charlie Baker’s office for a final signature. We encourage lawmakers in Massachusetts to support this policy measure and join advocates from across the country in recognizing that the pernicious, profit driven trend of replacing in-person visits with video chats is an unacceptable one.

Update, April 13 2018: Gov. Charlie Baker signed this bill into law. See coverage by the State House News Service, or a more detailed breakdown of the bill from state Sen. William Brownsberger.

D.C. will no longer suspend driver's licenses for drug offenses completely unrelated to driving, but 12 states still cling to failed law.

by Aleks Kajstura,

March 23, 2018

Residents of D.C. will no longer have their driver’s licenses automatically suspended for drug offenses completely unrelated to driving. Not that it ever made sense to do so in the first place.

The new law ending the practice passed back in November with unanimous support from the D.C. Council and the Mayor. Then, because all D.C. laws must be vetted by Congress, implementation of the law was delayed until last month.

But it’s never too late to reform these old, outdated rules around license suspensions. How did D.C. end up in this mess in the first place? These odd laws were a product of the War on Drugs, when states were eager to pile on any sort of penalties for drug offenses. In 1991 Congress started supporting automatically suspending driver’s licenses for drug offenses, and states (and D.C.) jumped on the idea.

The decades since have proven that such tactics are ineffective as deterrents. And not only do these laws not work, but they actually cause harm: Suspending driver’s licenses for non-traffic offenses decreases public safety on the road while increasing recidivism for those affected. So at the very least, taxpayers are spending a lot of money on making themselves less safe.

So it’s no surprise that D.C. is finally joining the vast majority of states, and shedding these laws. Unfortunately, this common-sense move is not quite common enough: 12 states still suspend driver’s licenses for drug offenses completely unrelated to driving.

New research illustrates that many formerly incarcerated people never received a fair first chance at economic mobility, never mind a second one.

by Lucius Couloute,

March 22, 2018

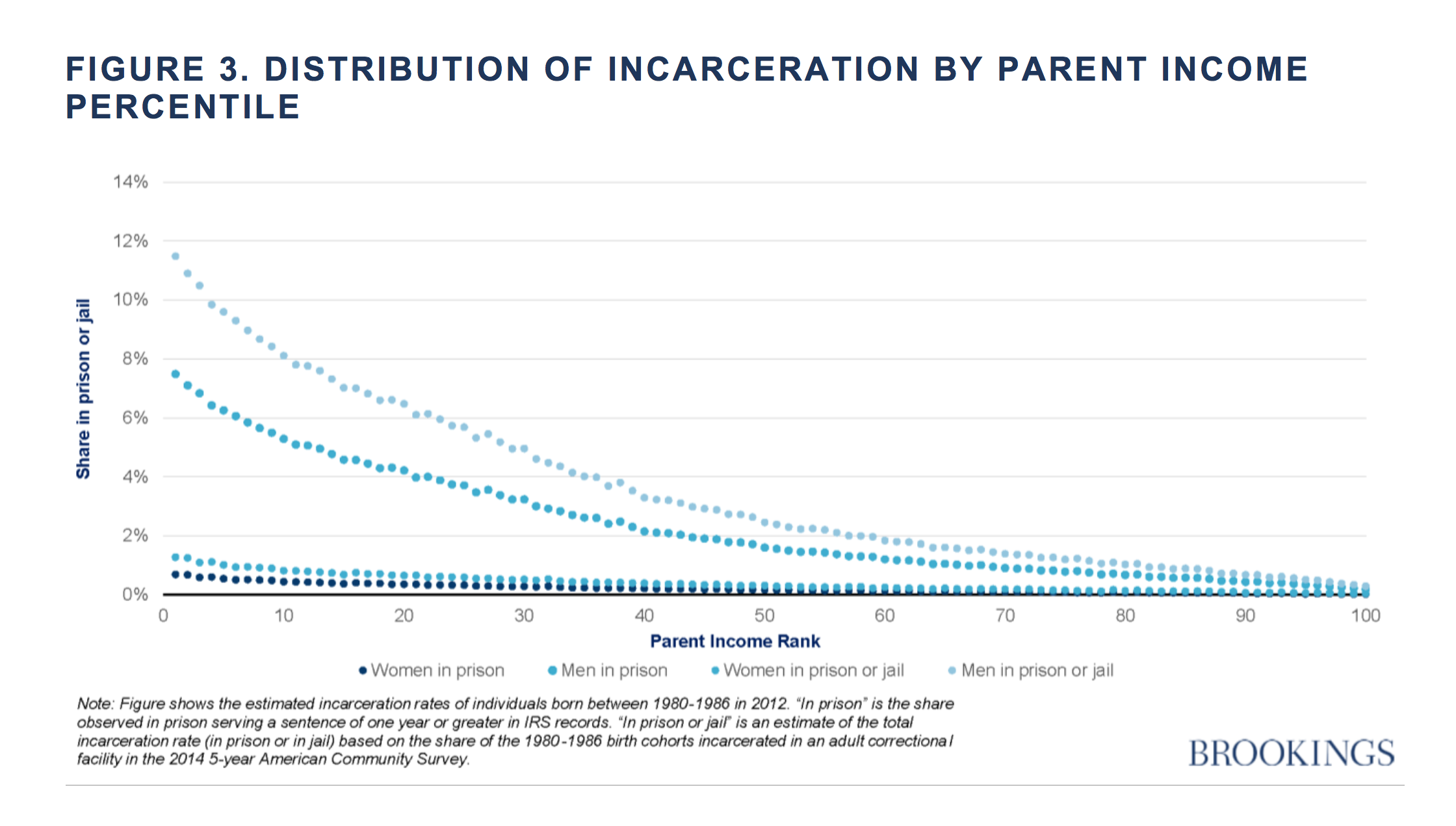

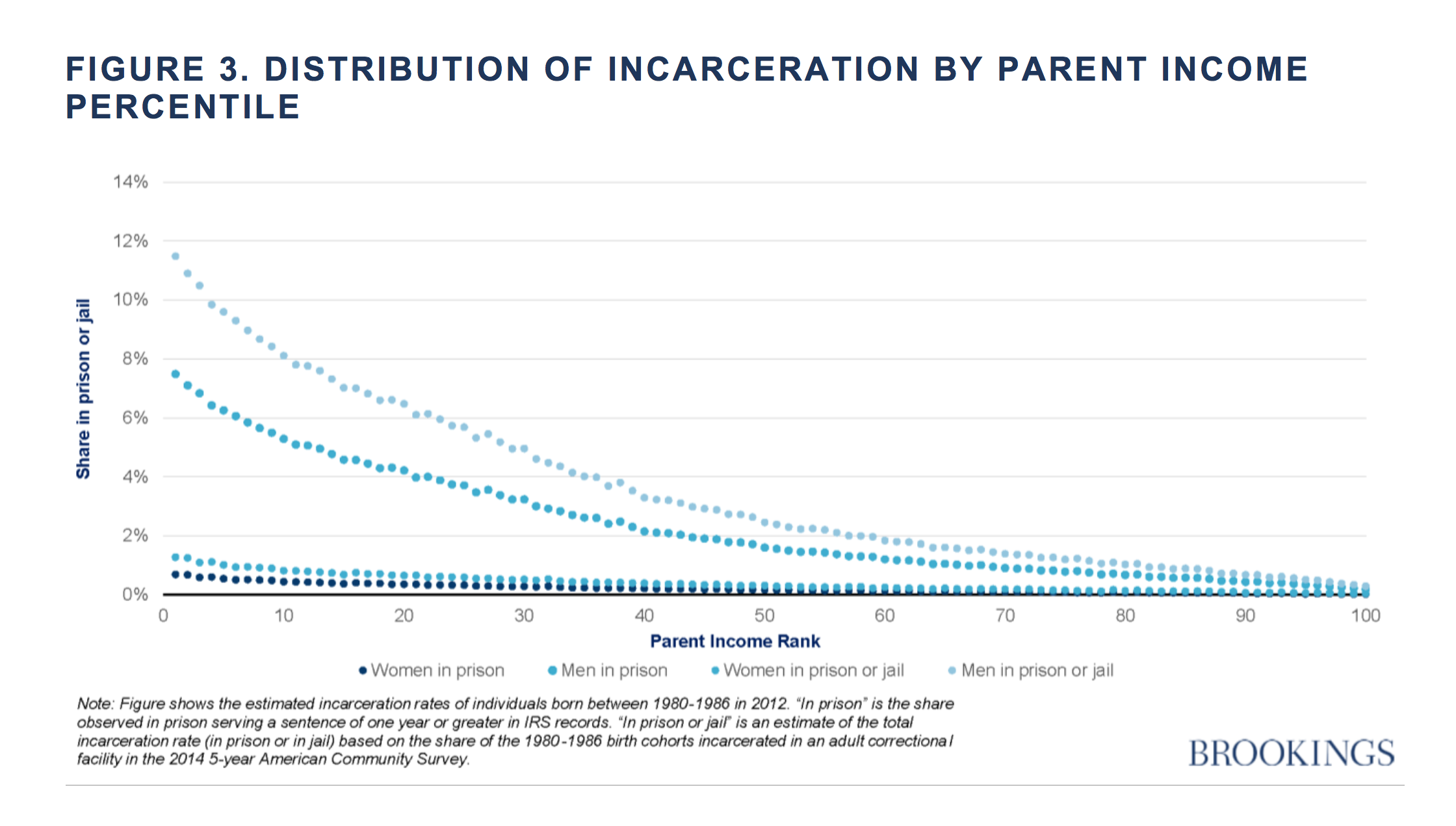

A striking report from the Brookings Institution, based on new IRS data covering almost 3 million people, shows how our criminal justice system targets people who were already socioeconomically disadvantaged prior to incarceration.

According to the authors, boys born into families at the bottom 10% of the income distribution are 20 times more likely to experience prison in their 30’s than their peers born into the top 10%. Although women make up a smaller share of the overall incarcerated population, the relative likelihood that they experience incarceration is similarly structured by early childhood family income.

Their analysis also shows that those who end up in prison disproportionately come from disadvantaged communities of color with high levels of poverty and unemployment. The data helps us recognize how mass incarceration operates as part of a system, funneling poor people of color from segregated neighborhoods into prisons, and eventually, back into society with little ability to gain an economic foothold.

Only about 53% of formerly incarcerated people report making any money – at all – in the formal labor market three years following their release. Part of the reason is that employers are unlikely to hire people with criminal records, despite growing evidence that blanketed discrimination against this population hurts employers.

But as we’ve argued in the past, the focus on the effects of incarceration sometimes overshadows how pre-incarceration poverty and opportunity structures determine who ends up behind bars in the first place. Report authors Adam Looney and Nicholas Turner, however, show that three years prior to incarceration, only about 49% of working-age people are employed, typically making less than $15,000 a year.

We often talk about reentry as an opportunity for incarcerated people to take advantage of some imagined second chance at life. Yet, this research suggests that the contemporary cultural framing around second chances is misleading at best. Many incarcerated people never received a fair first chance at economic mobility, never mind a second one.

The real impact of jail is far greater than the daily population suggests: People go to jail 10.6 million times each year. We collaborated with data journalist and illustrator Mona Chalabi to visualize just how vast a number 10.6 million jail admissions is.

by Wendy Sawyer,

March 22, 2018

This is one jail admission.

This is one jail admission.

A staggering 731,000 people are held in local jails across the U.S. every day. But the real impact of jails is actually far greater: People go to jail 10.6 million times each year. We collaborated with data journalist and illustrator Mona Chalabi to visualize just how vast a number 10.6 million jail admissions is.

Continue reading →

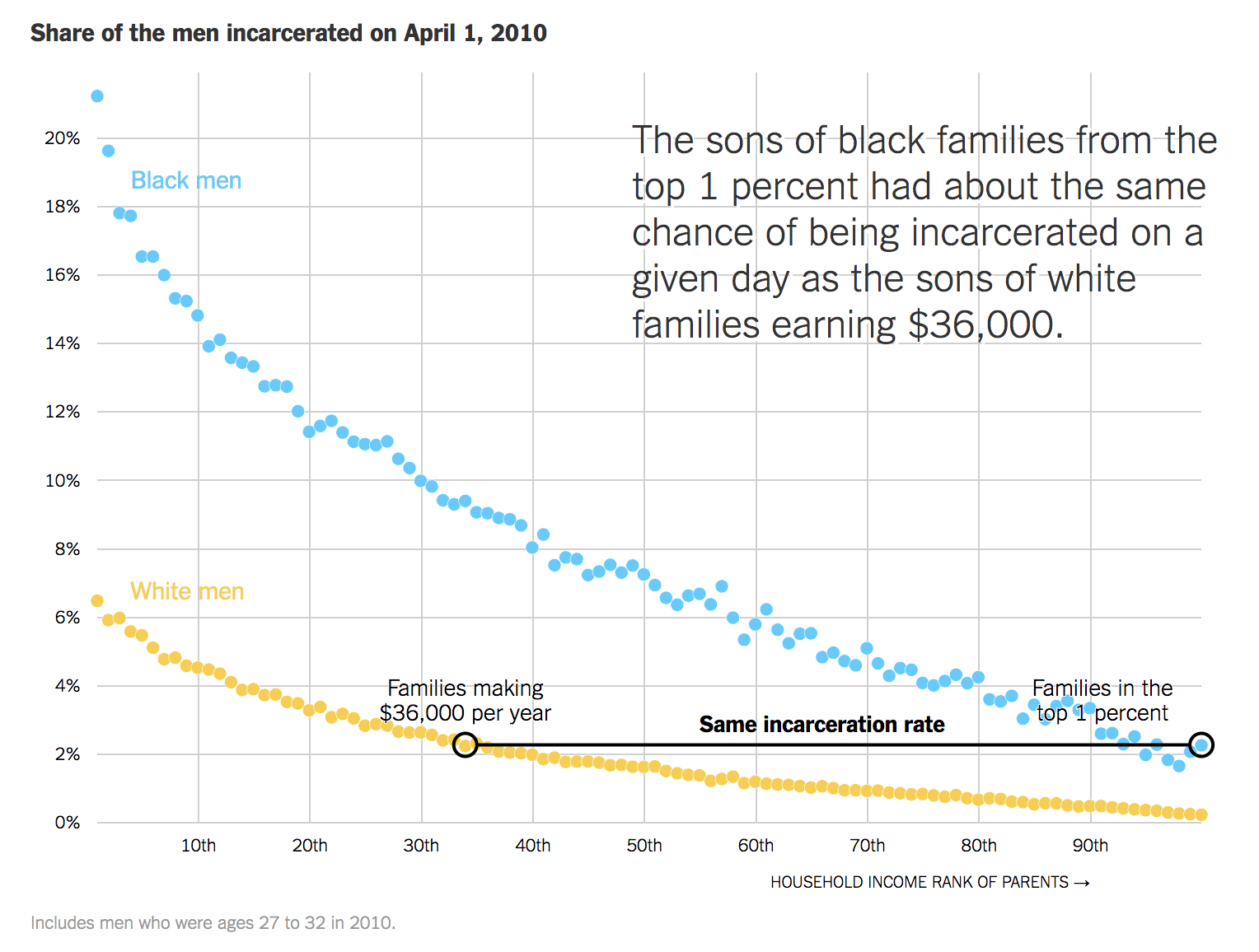

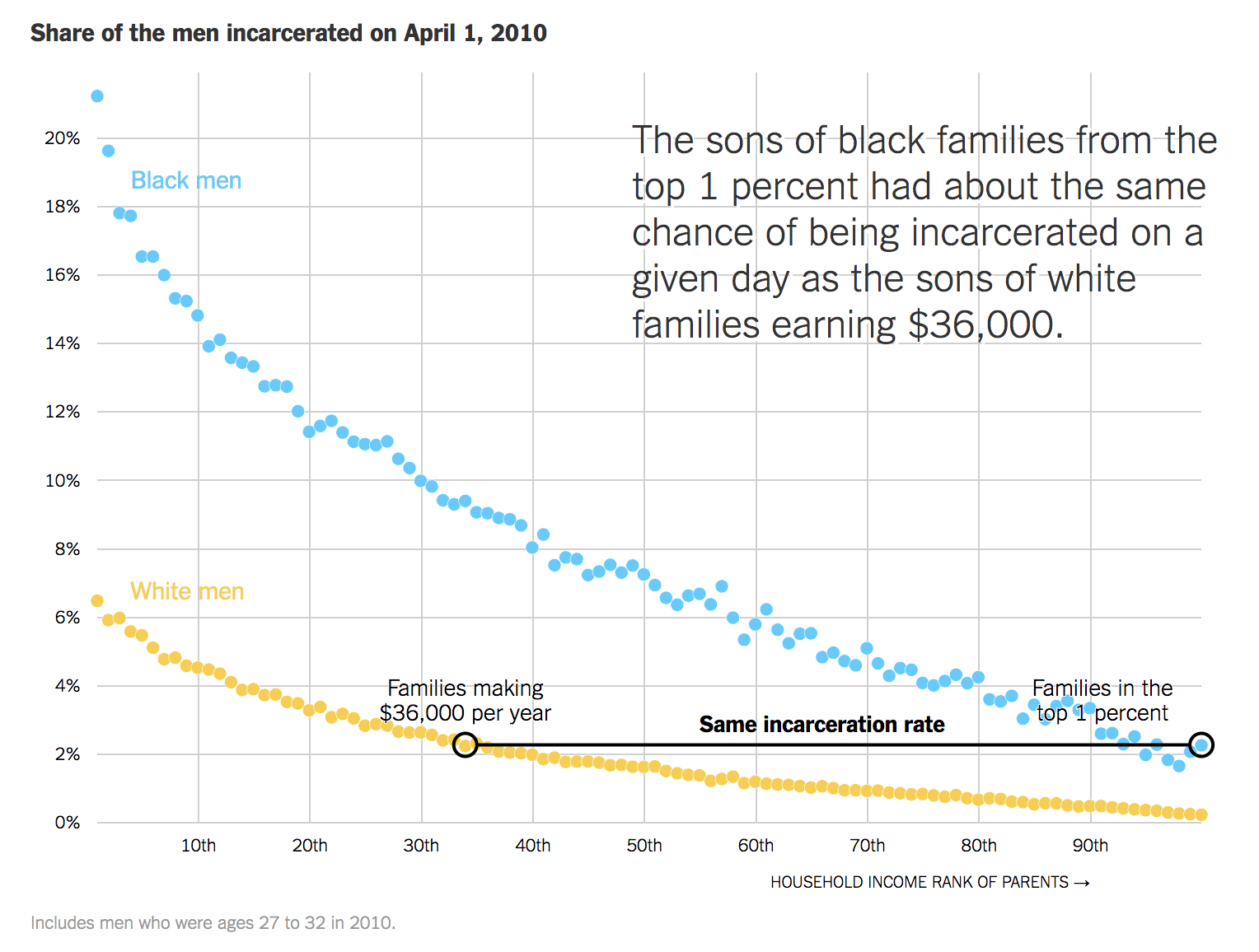

Racial biases in the criminal justice system don't only apply to poor people, according to research from Harvard, Stanford, and the Census Bureau.

by Wanda Bertram,

March 19, 2018

Racial biases in the criminal justice system don’t only apply to poor people, according to new research from Harvard, Stanford, and the Census Bureau covered in today’s New York Times:

“Black men raised in the top 1 percent – by millionaires – were as likely to be incarcerated as white men raised in households earning about $36,000.”

This helps explain why even Black boys from affluent families run a greater risk than their white peers of ending up poor. As a separate article in Race and Social Problems noted in 2016, the likelihood of incarceration is higher for Black people than for white people at every economic level. Incarceration also has a crippling effect on wealth accumulation, ensuring long-lasting damage to individuals, families, and communities of color.

While it’s critical that we explore the relationship between incarceration and poverty, it’s not so helpful to suggest that mass incarceration is driven by class “and not race.” As we point out in our Whole Pie report, the goal should be to implement reforms that both reduce the number of people incarcerated in the U.S. and the well-known racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice system.

Despite a drop in overall murder rates, the racial disparities in male murder victimization rates have persisted.

Despite a drop in overall murder rates, the racial disparities in male murder victimization rates have persisted. Overall, Black, Hispanic or Latinx, and American Indian and Alaskan Native people are murdered at much higher rates than their white or Asian and Pacific Islander counterparts.

Overall, Black, Hispanic or Latinx, and American Indian and Alaskan Native people are murdered at much higher rates than their white or Asian and Pacific Islander counterparts. The violent crime rate (yellow) peaked in 1991. The fear of crime (orange) peaked nine years earlier and was already declining when the violent crime rate was approaching its peak.

The violent crime rate (yellow) peaked in 1991. The fear of crime (orange) peaked nine years earlier and was already declining when the violent crime rate was approaching its peak.

This is one jail admission.

This is one jail admission.