Arielle Sharma reports back on her week working on prison gerrymandering research and sentencing enhancement zone messaging development.

by Arielle Sharma,

March 19, 2014

I spent the last week here at PPI for an Alternative Spring Break. I am from Connecticut, went to Boston University and am now at University of Connecticut Law School. I was excited to spend my week at PPI because of the excellent work they do to document the effects of mass incarceration with real numbers. I think my interest in prison began at a young age. I am of mixed race, half Indian and half Israeli. I had family who had been put in “prisons” during the Holocaust in Europe, and on my father’s side, I had family put in prison for marching with Gandhi. When I was young, the people I knew who had been in prison were not bad people. Too often, we dismiss incarcerated people because they are or have been deemed ‘criminals’ by society. Whether or not they have broken a law, they are still people who must be treated with respect.

2014 Alternative Spring Break Law Interns Arielle Sharma (right) and Corey Frost (left) at the Connecticut State House.

2014 Alternative Spring Break Law Interns Arielle Sharma (right) and Corey Frost (left) at the Connecticut State House.

This week, I was able to work on a project explaining one way in which exploitation of incarcerated people undermines the democratic rights of those of us not in prisons- Prison gerrymandering. Prison gerrymandering lessens the voice we have in our government. When the area each elected official represents is distributed based on population, people in prisons are sometimes used to boost numbers in certain areas even though the prisoners have no vote in government. This means that people who live near a prison get more of a say because the representative they elect is not serving the prison population and so each vote cast by the actual residents of the district is counted more.

This week, I continued the research on how/if this gerrymandering is happening on one of the most local scales: school board elections. (Fun fact I wish my school board had taught me in high school: School boards have A LOT of power. In many places, they have a say in curriculum, extra-curriculars, budgets, and some hiring and firing decisions) Even though school boards may seem too small to matter, the effects of prison gerrymandering actually become greater as the total population gets smaller. In my research, I found a majority of school boards don’t have problems with prison gerrymandering because they have at-large elections, which means everyone gets to vote for every school board member in their area, regardless of where they live. They are all sharing their voting power with each other, so everyone’s vote weighs the same.

I learned Bureaucracy is no joke. We all know the outcome of policy decisions, but few know how we’ve gotten to the system we have. Luckily, 99% of the people talked in the schools and town halls were super nice. Unluckily, these fine folks generally haven’t spent a lot of time thinking about prison gerrymandering. I called school boards in New Jersey, Connecticut, Missouri, Michigan, Alabama and Colorado. After many questions, many gentle rephrasings and many call transfers, I found two schools districts that allocate voting power based on population:

- The people lines in RE-1 Valley School District in Sterling, CO were super on top of things, and were savvy enough to take out their prison population.

- Despite a lot of help from a lot of people in Hunterdon County, NJ, it is still unclear if prison populations are kept in when North Hunterdon-Voorhees Regional board member districts.

Either way, the Supreme Court has supported ending prison gerrymandering and more than 200 local governments have already ended it on their own so hopefully this will soon be moot on every level.

PPI works on a lot of issues, so I had the luck to help on some other problems, too. I went with Aleks who was testifying in Connecticut on a bill trying to at least lessen the enhanced penalty zones (currently a 1500ft radius) for selling or possessing drugs around a school, public housing, or day care. Of course, research shows that kids are far more likely to get drugs from each other than random adults.

But in addition to that, the zones are way too big to make a difference in deterring drug activity away from schools. In Connecticut, school zones are 1500 feet. Do you know how far that is? You could lay the empire state building on its side, and still have a few hundred feet to spare! That’s way too long (Watch this guy free climb 1500ft mountain and then tell me that’s not a crazy distance- the video doesn’t even get all the way to the top!).

When whole cities are turned into enhanced penalty zones, where is the incentive to specifically stay away from schools? Instead, zone policies end up giving extra penalties to people who are often doing things in their own homes (over 90% of some Connecticut cities’ residences are in these zones). Plus, the areas aren’t marked so there is no way to tell if you’re on the bad side of the line (assuming the other side hasn’t put you into another school zone).

Prison gerrymandering and enhanced penalty school zones are just two of the MANY things going on at PPI, make sure to check out the rest of the site for more!

-Arielle

Conn. Judicial Committee hears testimony in favor of sentencing enhancement zone reform.

by Aleks Kajstura,

March 13, 2014

Yesterday, I testified before Connecticut’s Judiciary Committee in support of reforming Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement laws (my testimony starts at 3:34:03).

Connecticut’s 1,500-foot sentencing enhancement zones, meant to protect children from drug activity, are some of the largest in the country. I described how the law’s sheer expanse means it fails to actually set apart protected areas and that it arbitrarily increases penalties for urban residents. As Senator Holder-Winfield concisely explains, Senate Bill 259 would decrease that size to a more effective 200 feet.

For more details, check out the video above and my written testimony (with maps).

And check back in soon, I’m releasing a report examining Connecticut’s sentencing enhancement zones on the 28th.

Professor Owens teaches in the Political Science department of Emory University, and joined our board in January.

by Leah Sakala,

March 13, 2014

We are thrilled that Professor Michael Leo Owens has joined our Board of Directors this year. Professor Owens teaches in the Political Science department of Emory University, and specializes in urban, state and local politics, political penology, governance and public policy processes, religion and politics, and African American politics. We asked him a few questions about his work and involvement with PPI:

Why did you decide to join the PPI board?

Michael Leo Owens: As the piece of political science wisdom goes, “People participate when they can, when they want to, or when they’re asked.” My participation with PPI’s board covers all three bases! And I made a deliberate decision to leave another board of directors for PPI’s board. The switch is a better fit of interests, passions, and concerns.

What does your work focus on?

MLO: I’m a scholar of American politics and pubic policy. The politics of punishment and the civic effects of mass incarceration fill a big portion of my research, teaching, and service portfolio. In particular, I’m writing a book, Prisoners of Democracy, about the ways in which punitive public policies and ambivalent public opinion diminish the citizenship of people with felony convictions and undermine the positive reintegration of formerly incarcerated people. Additionally, I serve on the advisory boards of two other organizations that confront the challenges and consequences of “penal harm” – the Georgia Justice Project and Foreverfamily. The former provides defense counsel, social services, and advocacy for indigent persons. The latter, formerly known as Aid to Children of Imprisoned Mothers, is an Atlanta-based but national youth development organization, one that among other activities provides children with monthly visitations with their incarcerated parents.

What do you think is most unique about the Prison Policy Initiative and the projects it takes on?

MLO: What makes PPI unique is its moxie. It takes on BIG issues for a small organization and it’s successful in tackling them. Plus, by using data in a democratic way it increases the likelihood of community-based groups getting involved and taking the lead on their own behalf. Few data-driven organizations truly empower other groups. I’m glad PPI is one of them.

What’s something that you wish more people knew about the Prison Policy Initiative?

MLO: I wish more people knew that PPI is about more than prison gerrymandering. I also wish that more policymakers, especially in the South, knew of its existence and successes at making criminal justice more just and effective.

Our newest briefing includes the first graphic we’re aware of that aggregates the disparate systems of confinement in this country into one big-picture chart.

March 12, 2014

Ever wonder exactly how many people are locked up in the U.S. and why? Many people, interested citizens and policy wonks alike, find that seemingly simple question to be frustratingly difficult to answer. Until now.

Today, the Prison Policy Initiative releases its newest briefing, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, that includes the first graphic we’re aware of that aggregates the disparate systems of confinement in this country into one big-picture chart:

As we discuss in our briefing, this broader context pulls back the curtain and reveals answers to questions such as:

- How many people are behind bars for drug offenses?

- Which system holds more people: state prisons, federal prisons, or local jails?

- How many kids are locked up for offenses that most people don’t even think of as crimes?

- Where do we even have to look to find everyone who’s behind bars for immigration-related issues?

At the end of the day, locking up the more than 2.4 million people represented on this pie chart gives the United States the dubious distinction of being the number one incarcerator in the world. Policymakers and the public both have a pressing responsibility to take a good hard look at each slice of this pie and weigh any potential benefit of keeping those people behind bars against the significant social and fiscal cost.

The Prison Policy Initiative is thrilled to be chosen as one of three CharitySub organizations addressing this month’s “prison epidemic” theme.

by Peter Wagner,

March 3, 2014

The Prison Policy Initiative is thrilled to be chosen as one of three CharitySub organizations addressing this month’s “prison epidemic” theme.

The Prison Policy Initiative is thrilled to be chosen as one of three CharitySub organizations addressing this month’s “prison epidemic” theme.

CharitySub is an innovative new approach to online giving. CharitySub members pledge $5 a month, and each month CharitySub picks a new cause and identifies three non-profits making a difference on that cause. Each month, CharitySub members get to pick which of the three organizations receives their $5.

You can join today to support this month’s organizations and learn about other organizations doing great work in the future.

"[I]f left unregulated, the video communication market could follow the trajectory of the infamously broken prison telephone industry."

by Leah Sakala,

February 28, 2014

Prison Policy Initiative Executive Director Peter Wagner weighed in this week on a New York Times Room For Debate discussion about video visitation in prisons and jails. As Peter explained,

With proper regulation and oversight, prison and jail video communication has the potential to offer additional avenues for critical family communication. But if left unregulated, this market could follow the trajectory of the infamously broken prison telephone industry, dominated by the same corporations.

For more of our work on the prison and jail video visitation industry, check out our FCC filing on the subject and the New York Times editorial that it inspired.

As an undergraduate sophomore studying comparative politics at Smith College, this nonprofit granted me skills that exceeded my expectations.

by Catherine Cain,

February 27, 2014

Over the month of January, I worked full-time with the Prison Policy Initiative for three consecutive weeks. As an undergraduate sophomore studying comparative politics at Smith College, this nonprofit granted me skills that exceeded my expectations and any of my previous experiences with research.

Before working with PPI I had been building a potential passion for prison justice. In my prior work with the legal department at El Sol Neighborhood Resource Center, I became more aware of racial profiling and its effect on immigrant communities. That same summer the Trayvon Martin case sparked protests against Stand Your Ground laws. I delved into documentaries, such as The House I Live In, and flipped through The New Jim Crow as I began to think about these issues within the context of mass incarceration. Although I had become engaged in these issues, I had not yet developed an agenda to act upon this interest.

As soon as I heard about the Prison Policy Initiative, I got in contact with a friend interning with them. I browsed their website and was impressed by their presence on social media pages. I did not have a strong idea what prison gerrymandering was before coming across the Prison Policy Initiative, but I quickly found videos of Executive Director Peter Wagner explaining this and other concepts central to this nonprofit’s mission.

My first project was creating a state legislator outreach database. Our goal was to find state legislators that have passed “progressive” bills relating to PPI’s efforts in order to have them as a contact regarding these issues in the future. Through this project I became more fluent in the bill-making process. While I understood that the War on Drugs and related legislation significantly contribute to the United States’ alarmingly high incarceration rate, I also became familiar with bills addressing mental health of incarcerated people, lowering the size of drug free zones, repealing mandatory minimum sentences, decriminalizing marijuana and other “soft” drugs, and requiring racial impact statements.

By individualizing each letter, the initiative could quickly connect with the legislator. The last thing we wanted was to spam them with generic pages of information because it would simply waste both the legislator’s and our time. I was surprised at how much thought went into the legislator’s response on behalf of Peter and Leah, who guided me through this project. At the end of my time with PPI, we sealed 200 customized letters and sent them to their respective offices.

My second project with the Prison Policy Initiative was crosschecking their internal Locator database against census data to ensure that correctional institution populations match up. Locator files are organized by state, giving the incarcerated population for census blocks and matching these blocks to specific facilities. This is essential to PPI’s work for identifying and addressing circumstances of gerrymandering.

So how do you find prisons? State and Federal facilities are much easier to find online than local facilities (i.e. county jails). Florida’s Department of Corrections actually has great and up-to-date information on their state and local facilities. These were extremely useful when matching up incarcerated populations. Apart from the Locator tool, the Initiative has extensive resources that allow you to look at facilities for each state through Google Earth and Google Maps among other excellent features.

Most of the research I did at PPI used tools to navigate raw data with rather than swimming through secondary sources, as I had been used to within my academic endeavors. Although this intimidated me at first, I received tremendous support from the staff at PPI.

Throughout my time here, I continuously felt like an equal — intellectually and on a personal level. For example, since I am focusing on comparative politics in my studies, I was asked to give feedback on an upcoming project on international incarceration rates. First of all, I thought this was a great idea to publish on the website. But I was really pleased that my opinion was so valued by a strong non-profit like PPI. This sentiment did not fade throughout my time here.

At some point, every staff member at PPI pulled me aside to show me what they’re working on. I read letters from incarcerated people who came across the Prison Policy Initiative, was asked for feedback on an upcoming presentation, and was introduced to Peter Wagner’s favorite books about American criminal justice system. Even on my last day of work, I was encouraged to chime in on conversations about PPI’s next moves.

Peter and Leah wrote a new Huffington Post piece about the start of the FCC's inter-state prison phone rate regulation on Tuesday.

by Leah Sakala,

February 13, 2014

To celebrate the FCC’s inter-state prison phone call charge regulation going into effect on Tuesday (just in time for Valentine’s Day!), Peter and I wrote a new piece for the Huffington Post.

The FCC’s regulation is a huge milestone in the decade-long fight for fair phone charges for the families of incarcerated people, and there’s lots more to be done. As we wrote:

…the fight for fair phone charges is one that the families of the 12 million people cycling through jails each year can’t afford to lose. Interstate rate regulation was a huge step forward that must now be defended in court, and the FCC and state and local governments need to keep going in order to protect all families, regardless of whether their loved ones are incarcerated in the same state or elsewhere. Our movement is strong, and we’re committed to ensuring that all parents, partners, and kids can afford to affirm their love for one another over the phone next Valentine’s Day.

We also spoke with American Public Media’s Marketplace yesterday for a story on the FCC’s prison phone regulation.

For more on what this regulation means for families and friends, check out the Campaign for Prison Phone Justice’s great new FAQ.

The two largest prison phone companies, mislead correctional facilities and federal regulators by acting like communications technology is stuck in the 1950s.

by Peter Wagner,

February 11, 2014

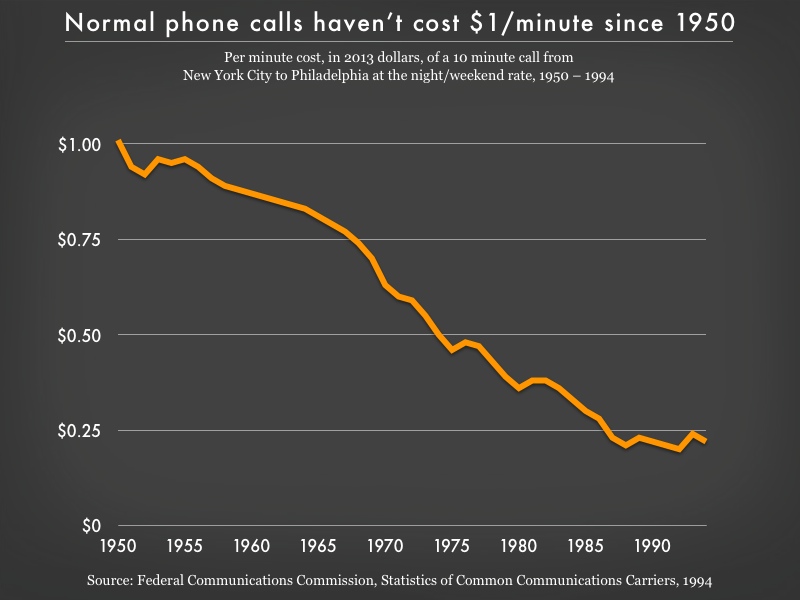

Today is a historic day: the Federal Communications Commission’s new rules take effect that cap the cost for inter-state calls home from prison and jail at a still-expensive but much-improved rate of 21 to 25 cents per minute. The FCC is exploring expanding its regulation to apply to the bulk of calls which are in-state in nature, and other important proposed restrictions have been stayed by the federal courts while prison telephone giants like Securus and its corporate allies sue the federal government for daring to end the industry’s monopolist price gouging.

As we’ve demonstrated in several lengthy reports and filings to the FCC, the high cost of phone calls from prison is driven by a kickback system in which private companies get monopoly contracts in exchange for sharing the majority of the revenue with the same correctional agency that awarded the contract.

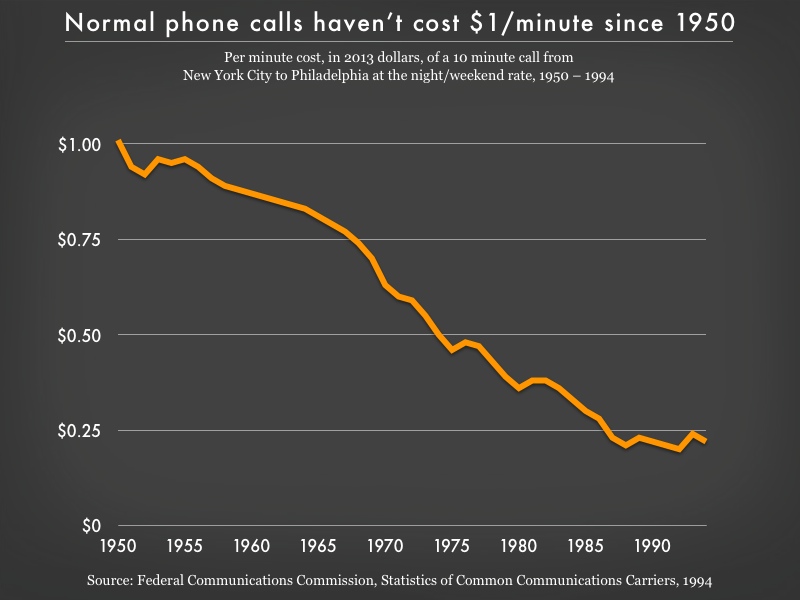

So while Securus sues to protect its windfall profits off the backs of families, I’d like to point out just how far out of step rates like $1/minute are in a world of modern electronic communications.

Contrary to what the phone companies would have you believe, important security technology isn’t what’s driving the cost of these calls. In fact, a call home from New York State prisons costs 4.8 cents a minute because that state refuses kickbacks and negotiates the contract on the basis of the lowest cost to the consumer. But the very same company charges close to $1/minute in other states. As we’ve said again and again, it’s all about the profit.

But aside from the contemporary arbitrariness of the charges in this industry, taking a look at the historical perspective sheds some additional light on why the FCC has to drag this industry kicking and screaming into the 21st century. You see, Securus and Global Tel*Link, the two largest prison phone companies, mislead correctional facilities and federal regulators by acting like it’s still the 1950s, when transmitting a long-distance call was a deeply expensive and laborious manual process.

Why do most prison and jail phone contracts assume that a long distance call requires an army of telephone operators like the ones in this photo from 1919?

Why do most prison and jail phone contracts assume that a long distance call requires an army of telephone operators like the ones in this photo from 1919?

Check out this radio dramatization from Dragnet of a long distance call in 1954. That tedious 1 minute 22 second process wasn’t much better than the very first inter-continental telephone call in 1919, which took 5 operators 23 minutes to connect Alexander Graham Bell with his former assistant Thomas Watson. Fortunately technology has vastly improved since then, and these days prison and jail telephone companies sell digital communications products for which distance is simply not a factor. These companies know, however, that it’s in their best interest to leave sheriffs in the dark about these 21st century technological advances. With the possible exception of some of the smaller companies that are pushing one-size-fits-all “postalized” rates, the phone corporations don’t appear to be lifting a finger to educate the sheriffs about the real cost of the telephone services being contracted.

The industry’s lack of transparency about the actual cost of providing telephone service is quite similar to its practice of hiding fees, which we discussed in detail in our second report. Essentially, the phone industry rakes in additional profit by tacking on extra fees and hiding them from the commission system. As a result, the sheriffs are led to believe that they have negotiated a good deal with the phone company, but the hidden fees preserve far more profit for the industry than it lets on. That’s why our report included an appendix with questions that the sheriffs should ask about fees when negotiating these contracts.

So, at the end of the day, how far out of whack is a $1 a minute phone call? We did some research to figure out the last time a regular U.S. long distance phone call cost $1 per minute. Adjusting for inflation, a call hasn’t cost that much since 1950:

Peter Wagner will discuss the hidden costs of mass incarceration on 2/10.

by Leah Sakala,

February 6, 2014

Western New England University has released a press release detailing Peter’s upcoming Clason Speaker Series talk, “Overdosing on prisons: Tackling the side effects of the United States’ globally unprecedented use of the prison” this Monday, February 10th:

Wagner will discuss the hidden costs of mass incarceration for our democracy, our economy, and public safety. A 2003 graduate of the Western New England University School of Law, Wagner co-founded the Prison Policy Initiative in 2001, building an independent study project into a national movement against prison gerrymandering. His efforts have led to new legislation in four states including Maryland, where the law he helped write was affirmed by the United States Supreme Court. Wagner’s work has been featured in hundreds of newspapers nationwide, winning editorial endorsements for criminal justice reform from such publications as The New York Times> and the Boston Globe.

This lecture is free and open to the public. Hope to see you there!

2014 Alternative Spring Break Law Interns Arielle Sharma (right) and Corey Frost (left) at the Connecticut State House.

2014 Alternative Spring Break Law Interns Arielle Sharma (right) and Corey Frost (left) at the Connecticut State House.