Census boon?

Some critics say districts with prisons are given too much aid, political clout

By Frank Green

Times-Dispatch Staff Writer

Monday, January 22, 2007

Del. Rosyln C. Tyler, D-Sussex, outside Greensville Correctional Center, says although her Southside district benefits by the inmate count, she would like to see a “better way to handle it” in the next redisticting. (Photo by Mark Gormus/Times-Dispatch)

Del. Roslyn C. Tyler, D-Sussex, represents a large, sparsely populated district in Southside Virginia where prisons have replaced agriculture as the major employer.

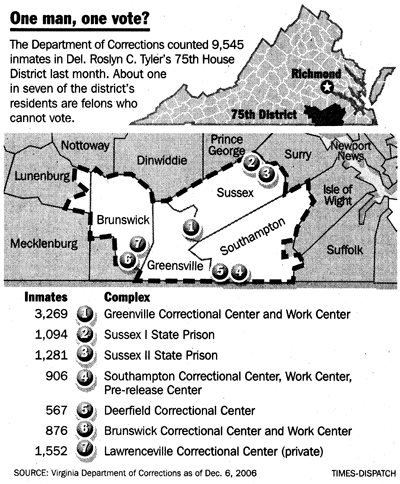

When Virginia’s 100 House districts were drawn in 2001, the aim was for each to have 70,785 residents. Tyler’s district, the 75th, wound up slightly smaller and included 9,184 state inmates, most of them from elsewhere and none of whom can vote.

Hosting nearly one third of all state inmates did not weaken the district’s political clout, however. Some experts say the prisoners not only strengthen it but earn localities within the district extra state aid.

“From the standpoint of one-person, one-vote, residents in the 75th have a disproportionate share of voting power in the state House,” says William Cooper, a census and redistricting consultant.

The U.S. Census Bureau counts inmates as residents of the places where the prisons are located, not where they call home. With the explosive growth in prisons in rural areas since 1980, critics say the policy distorts everything from redistricting to the way state revenue is dispersed.

General Assembly policy required the state’s 100 House of Delegates districts have populations no more than 2 percent higher or lower than 70,785, which was 1/100th of the state’s population as measured in the 2000 census.

The 75th was less than 2 percent smaller than the ideal population in 2001.

“From the standpoint of one-person, one-vote, residents in the 75th have a disproportionate share of voting power in the state House.”

William Cooper, a census and redistricting consultant.

Remove the 9,184 state prison inmates then in the 75th, and the district’s population would be 14 percent to 15 percent smaller than the ideal population, says Cooper, who lives in Bristol.

Eric Lotke, an expert on the economic impact of counting inmates in the census, says that could mean “every person there is worth 1.15 persons everywhere else.”

Lotke said there are other ramifications.

For instance, he found that the population gain in Sussex County — part of the 75th — caused by the opening of two prisons in 1998 and 1999 earned it an extra $120,700 in state funds for public education in fiscal year 2003.

Conversely, under the state’s complex formula for dispersing such aid, the Richmond area — which has no prisons but is the source of a substantial percentage of state inmates — lost nearly $300,000 that year because of residents shipped to prisons in other parts of Virginia.

The 75th is an extreme case. The district has seven major prison complexes and includes all or parts of the counties of Greensville, Sussex, Brunswick, Lunenburg, Southampton and Isle of Wight; all of the city of Emporia and part of the city of Franklin.

While there are more than 35,000 state and federal prisoners in the state today, there were more than 7 million Virginians counted in the 2000 census.

House redistricting participants say the impact of prisons was not a major consideration in 2001 because the population of a given prison is fairly small compared with the overall population of a House or Senate district.

Also, Virginia, unlike some states, has taken steps to blunt the impact prisons have on redistricting where it would be the greatest — at the local level. Counties where more than 12 percent of the population is incarcerated can opt to ignore inmates when doing internal redistricting.

But that does not address the effects of state legislative and congressional districting, say critics.

In 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court established the one-person, one-vote principle, requiring each district to have the same population. Every decade state legislatures use the census to draw congressional and state legislative districts.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, since 1980, the population of state and federal jails and prisons in the U.S. has quadrupled, to more than 1.4 million.

Virginia’s state prison population grew from 8,700 in 1980, to roughly 31,000. There are also now more than 3,300 inmates in federal prisons in Virginia.

Peter Wagner, executive director of the Prison Policy Initiative, said were it not for the construction of new prisons, 56 counties in the U.S. that the census found to be growing would have declined in size.

In Virginia, the 2000 census found that the population of Greensville County rose from 8,853 to 11,560 in the decade that began in 1990. But the growth included 2,700 inmates shipped to a prison that opened there in 1990.

Using 2000 census figures and last month’s prison populations from the Virginia Department of Corrections, more than 28 percent of the people who live in Greensville County are behind bars.

Nearby Sussex County was found to be the fastest-growing in the country in 2000. But its population actually declined if inmates were excluded.

The same data indicates that in at least five counties — Brunswick, Buckingham, Greensville, Richmond and Sussex — more than 10 percent of residents are in prison, and in at least 15 counties more than 5 percent of the population is locked up.

Though Tyler’s district benefits, she would like to see things changed when redistricting is performed in 2011 based on the 2010 census.

“I believe that there should be a better way to handle it,” said Tyler, perhaps by counting inmates where they came from and not where they are held.

Preston Jay Waite, an associate director of the U.S. Census Bureau, does not agree.

“We wouldn’t know how to put them back. Suppose you’ve been in prison 15 years — do you still belong in the house that you were living in when you were arrested?” Waite said. Many prisons do not have reliable data on where the inmates came from, he noted.

“We’re supposed to count every resident in the United States,” Waite said. In order to be consistent, we say, ‘The correct place is where you live, where you stay, where you sleep most of the time.”

Virginia lawmakers know where the prisons are located, Waite said, and, “there’s nothing to stop the state of Virginia … from placing those prisons in whatever district makes sense to them.”

Lotke said the state, using data from the census, could simply subtract the inmates when redistricting. Adding inmates back as residents of the districts they came from would be harder, Lotke concedes. But, he insists, it can be done.

Tyler said it is a mystery to her how so many prisons wound up in her district.

Her predecessor, J. Paul Councill Jr., also a Democrat, held the seat for 32 years before retiring. He said that he believes the prisons were simply built there over the years, and their presence has little, if anything, to do with redistricting.

Del. S. Chris Jones, R-Suffolk, was a key player in Virginia’s House redistricting in 2001 — the first time in state history Republicans redistricted the House — and he also does not recall much discussion about prisons.

In 2001, the 75th’s boundaries were little changed from the 1991 redistricting performed by Democrats.

The census data showing where correctional inmates were located were not available until the summer of 2001, after the legislators redistricted, Cooper said. He developed the districting plan used by the Sussex County Board of Supervisors, which excludes inmates.

“The simple way is not to count them at all statewide,” he said. “It would be very simple for redistricting, but it would still not correct the funding issues.”

Wagner agrees. He noted the General Assembly passed a law for counties such as Sussex to address the problem.

“That’s the first step and that was the easy step,” he said. “Now they need to take that same principle and work with the Census Bureau to come up with a solution that will fix this problem at the state level.”

Contact staff writer Frank Green at fgreen@timesdispatch.com or (804) 649-6340.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.