Can you help us fight this industry and reunite families face to face?

Donate

Screening Out Family Time: The for-profit video visitation industry in prisons and jails

by Bernadette Rabuy and Peter Wagner

January, 2015

Executive Summary

Introduction

Every Thursday, Lisa* logs on to her computer and spends $10 to chat for half an hour via video with her sister who is incarcerated in another state. Before the Federal Communications Commission capped the cost of interstate calls from prisons, these video chats were even cheaper than the telephone. Lisa’s experience is representative of the promise of video visitation.

Meanwhile, Mary* flies across the country to visit her brother who is being held in a Texas jail. She drives her rental car to the jail but rather than visit her brother in-person or through-the-glass, she is only allowed to speak with him for 20 minutes through a computer screen.

Elsewhere, Bernadette spends hours trying to schedule an offsite video visit with a person incarcerated in a Washington state prison. After four calls to JPay and one call to her credit card company, she is finally able to schedule a visit. Yet, when it is time for the visit, she waits for 30 minutes to no avail. The incarcerated person did not find out about the visit until the scheduled time had passed. The visit never happens.

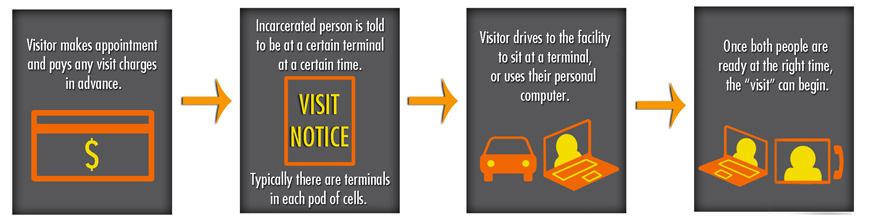

How do video visitations work? While video visitation systems vary, the process typically works like this:

Figure 1. Most companies, including Securus, Telmate, and Renovo/Global Tel*Link, charge for a set amount of time and require pre-scheduled appointments.

Figure 1. Most companies, including Securus, Telmate, and Renovo/Global Tel*Link, charge for a set amount of time and require pre-scheduled appointments.

Reviewing the promises and drawbacks of video visitation

Increasing the options that incarcerated people and their families have to stay in touch benefits incarcerated individuals, their families, and society at large. Family contact is one of the surest ways to reduce the likelihood that an individual will re-offend after release, the technical term for which is “recidivism.”1 A rigorous study by the Minnesota Department of Corrections found that even a single visit reduced recidivism by 13% for new crimes and 25% for technical violations.2 More contact between incarcerated people and their loved ones — whether in-person, by phone, by correspondence, or via video visitation — is clearly better for individuals, better for society, and even better for the facilities. As one Indiana prison official told a major correctional news service: “When they (prisoners) have that contact with the outside family they actually behave better here at the facility.”3

Without a doubt, video visitation has some benefits:

- Most prisons and some jails are located far away from incarcerated people’s home communities and loved ones.4

- Prisons and jails sometimes have restrictive visitation hours and policies that can prevent working individuals, school-age children, the elderly, and people with disabilities from visiting.

- It can be less disruptive for children to visit from a more familiar setting like home.

- It may be easier for facilities to eliminate the need to move incarcerated people from their cells to central visitation rooms.

- It is not possible to transmit contraband via computer screen.5

But video visitation also has some serious drawbacks:

- Visiting someone via a computer screen is not the same as visiting someone in-person. Onsite video visitation is even less intimate and personal than through-the-glass visits, which families already find less preferable to contact visits.

- In jails, the implementation of video visitation often means the end of traditional, through-the-glass visitation in order to drive people to use paid, remote video visitation.

- Video visitation can be expensive, and the families of incarcerated people are some of the poorest families in the country.6

- The people most likely to use prison and jail video visitation services are also the least likely to have access to a computer with a webcam and the necessary bandwidth.7

- The technology is poorly designed and implemented. It is clear that video visitation industry leaders have not been listening to their customers and have not responded to consistent complaints about camera placement, the way that seating is bolted into the ground, the placement of video visitation terminals in pods of cells, etc.

- Technological glitches can be even more challenging for lawyers and other non-family advocates that need to build trust with incarcerated people in order to assist with personal and legal affairs.

The industry and correctional facilities have largely focused on the promised benefits of video visitation, but reform advocates have long expressed their concerns. We found an article by a person incarcerated in Colorado all the way back in 2008 that nicely summarized both the promise and fear represented by video visitation:

“If video visits are an addition [to in-person visits] they will be a help to all and a God-send to many. But, if video visits are a replacement for the current visitation, their implementation would be a painful unwelcome change that would be impersonal and dehumanizing.”8

Video visitation reaches critical mass in 2014

Currently, more than 500 facilities in 43 states and the District of Columbia are experimenting with video visitation.9 Much of this growth has occurred in the last two to three years as prison and jail telephone companies have started to bundle video visitation into phone contracts. While there is not a detailed history of the industry’s growth, most sources trace the inception of the industry back to the 1990s.10

Now, in 2014, video visitation is ironically the least prevalent in state prisons, where it would be the most useful given the remote locations of such facilities, and the most common in county jails where the potential benefits are fewer. In contrast, jails typically implement video visitation in an unnecessarily punitive way. The differences between how prisons and jails approach video visitation are stark; Figure 2 summarizes our findings.

| County jails | State prisons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onsite | Regional visitation centers | Visit from home | Onsite | Regional visitation centers | Visit from home | |||

| Prevalence of video visitation type? | Common | Very rare. | Common | Never, with one exception. | Sometimes | Common | ||

| Cost? | Free, at least for the first few visits a week. | Free, at least for the first few visits a week. | $ | n/a | $ | $ | ||

| Does this require family members to travel long-distances? | Depends on the size of the county. | No | No | n/a | Not usually. | No | ||

| Operated by: | Private company, or the facility | Facility | Private company | n/a | State/non-profit partnerships | Private company | ||

| Prior to installation of video visitation, how are visits typically conducted? | In-person, through a glass barrier. | In-person, generally without a glass barrier. | ||||||

| After installation of video visitation, is in-person visitation typically abolished? | Yes | n/a | No | No | ||||

In the state prison context, the primary challenge to encouraging in-person visitation is distance, as many incarcerated people are imprisoned more than 100 miles away from their home communities and are sometimes even imprisoned in a different state.11 Most of the state prisons that use video visitation currently do so only in small experimental programs or as a part of a larger contract for electronic payment processing systems and email. Many of these experimental programs focus on special populations or special purposes.12 For example, New Mexico has a special program for 25 incarcerated mothers,13 and a number of other states use video systems for court and parole hearings.14 Other states like Virginia and Pennsylvania have regional video visitation centers that families can use, thereby reducing the distance that families must travel.15

Five states have large video visitation programs that are bundled with another service. Four states — Georgia, Indiana, Ohio, and Washington — contract with the company JPay, and another industry player Telmate runs a video visitation system along with phone services in Oregon. In all of these cases, prisons use video visitation very differently than jails do. Given that prisons hold people convicted of more serious crimes, one might expect that if any facility were going to ban contact visits and require visitation via onsite video terminals, it would be state prisons. However, state prisons understand that family contact is crucial for reducing recidivism, and burdening individuals with extensive travel only to visit an incarcerated loved one by video screen is particularly counterproductive. As Illinois Department of Corrections Spokesman Tom Shaer explained to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the state had no plans to eliminate in-person visits: “I can’t imagine the scenario in which someone would travel to a prison and then wish to communicate through a video screen rather than see a prisoner face-to-face.”16

In contrast, county jails confine people who are generally not far from home, and the majority are presumed innocent while they attempt to pay bail or await trial. The 40% of people in jail who have been convicted17 are generally serving a relatively short sentence for misdemeanor crimes. Despite the fact that jails should be particularly conducive to in-person visits, most jails have replaced contact visits with through-the-glass visits. And when jails implement video visitation, they typically replace through-the-glass visiting booths with a combination of onsite and remote paid video visitation.

Why families are unhappy with the state of the video visitation industry

Most families — the end-users of video visitation — are deeply unhappy with the combination of video visitation’s poor quality, the cost of visitation, and the fact that jails often force the service on them. Some of the specific problems that families frequently cite are without a doubt fixable. Others are the inevitable result of the failed market structure: the companies consider the facilities — not the families paying the bills — as their customers. The primary complaint is apparent: video visits are not the same as in-person visits and are much less preferable to contact visits or through-the-glass visits.

Sheriffs typically defend the transition from in-person, through-the-glass visits to video visits as being insignificant18 because both involve shatterproof glass and talking on a phone. To the families, however, replacing the real living person on the other side of the glass with a grainy computer image is a step too far.

A. Video visits are not equivalent to in-person visits

It is more difficult for families to ensure or evaluate the wellbeing of their incarcerated loved ones via video than in-person or through-the-glass. Families struggle to clearly see the incarcerated person with video visits and instead face a pixelated or sometimes frozen image of the incarcerated person. The poor quality of the visits only increases family members’ anxiety. For example, a mother interviewed by the Chicago Tribune described her unease at seeing her son’s arm in a sling during a video visit, and how she would have felt more assured about his health and safety if she could have seen him properly in a traditional visit.19 The physical elements that still remained in through-the-glass visits are now gone. As Kymberlie Quong Charles of advocacy group Grassroots Leadership told the Austin Chronicle, “Even through Plexiglass, it allows you to see the color of [an inmate’s skin], or other physical things with their bodies. It’s an accountability thing, and lets people on the outside get some read on the physical condition of a loved one.”20

![]() Figure 3. Visual acuity is important for human communication.

Figure 3. Visual acuity is important for human communication.

Second, companies and facilities set up video visitation without any regard for privacy. Video visitation is popular among jails because by placing the video visitation terminals in pods of cells or day rooms, there is no longer a need to transport incarcerated people to a central visitation room. Yet, the lack of privacy can completely change the dynamic of a visit. As an Illinois mother whose son is incarcerated in the St. Clair County Jail, Illinois explained, “I want to get a good look at him, to tell him to stand up and turn around so I can see that he’s getting enough to eat and that he hasn’t been hurt. Instead, I have to see his cellmates marching around behind him in their underwear.”21 In the D.C. jail, Ciara Jackson had a scheduled video visit with her partner canceled when a fight suddenly broke out. Jackson was upset that their “[5-year-old daughter] daughter could see the melee in the background” and told The Washington Post, “Before, in the jail, you were closer and had more privacy. This, I don’t know. This just doesn’t seem right.”22 Federal public defender Tom Gabel told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that his clients are equally dissatisfied: “They want to actually see the people who come to visit them, not look at them on a computer screen from a crowded pod…It’s just one more thing prisoners find impersonal at the jail.”23

Further, video visits can be disorienting because the companies set the systems up in a manner that is very different from in-person, human communication. Since the video visitation terminals were designed and set up with the camera a couple of inches above the monitor, the loved one on the outside will never be looking into the incarcerated person’s eyes. Families have repeatedly complained that the lack of eye contact makes visits feel impersonal.

Figure 4. This video demonstrates the importance of eye contact for human communication. (For the YouTube version, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lICUe6Ypeug.)

Figure 4. This video demonstrates the importance of eye contact for human communication. (For the YouTube version, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lICUe6Ypeug.)

Video visitation can add to the already significant trauma that children of incarcerated parents face, especially for young children who are unfamiliar with the video technology. Dee Ann Newell, a developmental psychologist who has been working with incarcerated children for 30 years, has witnessed traumatic reactions to video visitation from young children as well as from some of the older ones.24 Cierra Rice, whose partner is incarcerated in King County Jail, Washington told The Seattle Times that she does not bring her 18-month-old to video visits at the jail because he gets fidgety in the video visitation terminal and does not understand why he cannot hug his father.25

Notably, the San Francisco Children of Incarcerated Parents Bill of Rights demands greater protections of family-friendly visitation: “‘Window visits’, in which visitors are separated from prisoners by glass and converse by telephone, are not appropriate for small children.”26 If through-the-glass visits fall short for children, video visits are even more unacceptable.

B. Video visitation is not ready for prime time

Despite the commonly-made comparison, video visitation technology is not as reliable as widely-used video services such as Skype or FaceTime, and if video visitation is going to be the only option that some families have, it is nowhere near good enough. Families we interviewed who use onsite and offsite video visitation, including those who are experienced Skype and FaceTime users, consistently complain of freezes, audio lags, and pixelated screens in video visitation.27 Referring to Securus’s offsite video visitation system, Jessica* said that she has had video visits freeze for a full minute. By the time she was able to tell the incarcerated person that he froze, the visit would freeze again. In fact, Jessica does not think offsite video visitation is convenient. She calls it “almost a waste of money.” Families and friends have also complained about lost minutes, with visits failing to start on time despite both ends being ready or ending abruptly due to a technical malfunction. Sara* — a mother whose son is incarcerated in Maricopa County, Arizona — said that she and her son’s other visitors have had “continuous issues with connecting on time” and have lost up to five minutes. When visits are 20 minutes long, “five minutes is precious.”

Technical problems can be systemic. Clark County, Nevada is currently upgrading its Renovo video system to address the problem with the current system where “more than half of the average 15,000 visits a month were canceled because of tech issues.”28

C. Video visitation puts a price tag on a service that should be free

Much of the video visitation industry, particularly in county jails, is designed to drive people from what was traditionally a free service towards an inferior, paid replacement. Even where onsite video visitation is offered and free, it is often run in a limited way to further encourage offsite video visitation. Unfortunately, companies and correctional facilities negotiate the terms and prices without any input from the people that pay. Tom Maziarz of St. Clair County, Illinois’s purchasing department exemplified this disregard when he told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “A dollar a minute strikes me as a fair price. I guess it depends what viewpoint you’re coming from. The way I look at it, we’ve got a captive audience. If they don’t like (the rates), I guess they should not have got in trouble to begin with.”

Charging for visitation also means charging the families that are least able to afford this additional expense. These families are poor. In an extensive survey of previously incarcerated people, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 86% of respondents had an annual income that was less than $25,000.29 As with the prison and jail telephone market, charging for visitation is, at best, a regressive tax where the government charges the most to the taxpayers who can afford it the least. The Houston Chronicle editorial board condemned the practice of charging families for visits, declaring, “Making money off the desire of prisoners to be in touch with family members and loved ones is offensive to basic concepts of morality.”30

What this industry is doing: Major themes

While there are tremendous differences in the rates, fees, commissions, and practices in each contract, three significant patterns are common:

- Most county jails ban in-person visits once they implement video visitation.

- Video visitation contracts are almost always bundled with other services like phones, email, and commissary, and facilities usually do not pay anything for video visitation.

- Unlike with phone services, there is little relationship between rates, fees, and commissions beyond who the company is.

While virtually no state prisons31 ban in-person visitation, we found that 74% of jails banned in-person visits when they implemented video visitation. Though abolishing in-person visits is common in the jail video visitation context, Securus is the only company that explicitly requires this harmful practice in its contracts. The record is not always clear about whether the jails or the companies drive this change, but by banning in-person visits, it is clear that the jails are abandoning their commitment to correctional best practices.32

Video visitation is rarely a stand-alone service, and 84% of the video contracts we gathered were bundled with phones, commissary, or email. Sometimes it is obvious that the bundling of contracts persuades counties to add video visitation. For example, in a contract approval form, Chippewa County, Wisconsin’s jail administrator described how attractive this makes video visitation: “The installation and start-up of the Video Visitation is $133,415.00 and Securus is paying all of it.”33 The county was further incentivized because by adding video, call management services “went from a discount of 30% to 76.1%.” In Telmate’s contract with Washington County, Idaho, Telmate says it needs to bundle its contracts or else it will be unable to provide video visitation free of charge to the facility.34 In other words, in this county, Telmate apparently subsidizes the costs of video visitation equipment by charging families high fees to deposit funds into Telmate commissary accounts.

Since the contracts are negotiated with the understanding that the facility will not be required to pay anything, the facilities sign them without carefully looking at the real costs or who (the families) will be paying for the shiny new services. For example, in Dallas County, Texas, after a huge public uproar, the County Commissioners Court unanimously supported preserving traditional through-the-glass visitation and rejected Securus’s request to ban in-person visitation. But two months later, the County inexplicably approved a contract with Securus that included the installation of 50 onsite visitor-side terminals; terminals that would only be useful if in-person visitation were eliminated in the county.35 If the county were paying the $212,500 for those onsite visitor side terminals36 with its own — rather than families’ — funds, the county commissioners would have surely been less reluctant to question such a purchase.

In the prison and jail telephone industry, there is a well-documented correlation between rates, fees, and commissions that surprisingly does not exist in the video visitation market even though many of the same companies are involved.37 In the phones market, the facilities demand a large share of the cost of each call, and these high commissions create an incentive for the facility to agree to set high call rates. In turn, the companies respond to the demand for high commissions by quietly tacking on new and higher fees to each family’s bill.38

In the video visitation industry, this cycle does not appear to exist. Instead, to the degree that rates, fees, and commissions are related to anything at all, the details of the contract are most dependent on the company. We report the typical rates and commissions for some of the industry leaders in Figure 5.

| Rates found | Typical rate | Commissions found | Typical commission | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HomeWAV | $0.50 – $0.65/min | $0.50/min | None – 40% | n/a |

| JPay | $0.20 – $0.43/min | $0.33/min | 0.75% – 19.3% | 10% |

| Securus | $0.50 – $1.50/min | $1/min | None – 40% | 20% |

| TurnKey Corrections | $0.35 – $0.70/min | $0.35/min | 10% – 37% | n/a |

| Telmate | $0.33 – $0.66*/min | n/a | None – 50%* | n/a |

While Securus’s rates are significantly higher than those of other companies, Securus does not provide jails with higher commission percentages. In fact, the lowest commission among the jail contracts can be found in Maricopa County, Arizona, which receives 10% of Securus’s total gross revenues from video visitation. Overall, commissions are lower for video visitation than they are for phones.39 Oddly, the rates still varied among the few jails that do not accept commissions (Figure 6). It seems that sometimes negotiating to a lower commission may bring down the rate charged to families while other times it does not.

| County | Company | Rate | Typical company rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adams County, MS | HomeWAV | $0.50/min | $0.50/min |

| Champaign County, IL | ICSolutions / VizVox | $0.50/min | $0.50/min |

| Dallas County, TX | Securus | $0.50/min | $1/min |

| Douglas County, CO | Telmate | $0.33/min | n/a |

| San Juan County, NM | Securus | $0.65/min | $1/min |

| Saunders County, NE | Securus | $1/min | $1/min |

The companies also differ in how they charge families. Almost all of the companies charge families per visit rather than per minute, which raises questions about whether families receive the full value that they pay for, especially since it is common for the image to freeze:

| Company | Per minute or per visit? |

|---|---|

| HomeWAV | Per minute |

| ICSolutions / VizVox | Per visit |

| JPay | Per visit |

| Renovo | Per visit |

| Securus | Per visit |

| Telmate | Per visit |

| TurnKey Corrections | Per minute |

As in the phone industry, the size of the hidden fees that add to the cost of each visit varies considerably. But unlike the phone industry, where “[a]ncillary fees are the chief source of consumer abuse and allow circumvention of rate caps,”40 the fees for video visitation vary from burdensome to nonexistent. In fact, some of the high-fee companies in the telephone industry are the very same ones who do not charge any credit card fees for video visitation:

| Company | How to pay for video visit | Fees |

|---|---|---|

| HomeWAV | Buy minutes on PayPal using credit/debit card, bank account, or prepaid gift card | $1 |

| ICSolutions / VizVox | Fund prepaid collect account online with a credit/debit card or through Western Union or money order | $0 fee + taxes to $9.99 Western Union fee + taxes, See Exhibit 11 |

| JPay | Pay with credit/debit card when you schedule visit online or by phone | $0 |

| Renovo | Pay with credit/debit card or prepaid credit/debit card when you schedule visit online | $0 |

| Securus | Pay with credit/debit card when you schedule visit online | $0 |

| Telmate | Fund your Friends & Family account (various methods) | $2.75 – $13.78 fee, See Exhibit 11 |

| TurnKey Corrections | Fund your communications account (various methods) | $0 – $8.95 fee, See Exhibit 11 |

Broken promises from the industry and its boosters

The video visitation industry sells correctional facilities a fantasy. Facilities are pitched a futuristic world out of Star Trek where people can conveniently communicate over long distances as if they were in the same room while simultaneously helping facilities bring in revenue and eliminate much of the hassle involved in offering traditional visitation. In turn, the facilities sell these same benefits to the elected officials who must approve the contracts. But when hard lessons of experience bring down those dreams, the industry and the facilities are less forthcoming. This section reviews the record to date on the promises made by the industry and its boosters.

Our findings put the industry’s promises into question:

- Increased safety and security? The industry says, without evidence, that video visitation — and the “investigative capabilities”41 of these systems — will make facilities safer, primarily by eliminating contraband. In the one study of this claim, Grassroots Leadership and the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition found that disciplinary cases for possession of contraband in Travis County, Texas increased 54% after the county completed its transition to video-only visitation.42 Correctional facilities tell elected officials that video visitation can also eliminate “fights in the lobby,”43 but the public location of the terminals actually increases tensions in the cell pods. As a person incarcerated in Collier County, Florida described: “Everybody in the dorm or on the pod can still see who it is that’s visiting another. This in itself is invasive and potentially compromising and has led to fights among the inmates here.”44

- Increased efficiency and cost savings for the facility? The industry tells the facilities that they can outsource handling families’ complaints, but when the systems do not work, it is the facilities that are left filling in the gaps of a system they neither designed nor control.45

- A lucrative source of revenue for the facility? The available data reveals that video visitation is not a big money maker for facilities and may not even be profitable for the industry. First, refunds are common. For the month of August 2014, Charlotte County Jail, Florida and company Montgomery Technology, Inc. gave 35 refunds out of 89 total video visits. The facility and Montgomery Technology, Inc. did not gain revenue; each lost $8.46 Second, the contracts are often structured in a way that serves the needs of the industry before the needs of the facilities.47 In some cases, facilities must meet these unreasonably high usage requirements48 set by companies as a prerequisite to receiving commissions. In other cases, video visitation companies require that their investments be recouped before they will pay commissions to the facilities. If this clause were in effect in Travis County, Texas — one of the few jurisdictions that have made commission data available — it would take 17 years before Travis County would receive commissions.49 In Hopkins County, Texas, Securus anticipated that the county would generate $455,597 over five years from its 70% commission on video visits and phone calls. However, in the 2014 fiscal year, Hopkins County earned a mere 40% of the expected yearly revenue.50

- Families will readily embrace remote video visitation? Securus told Dallas County, Texas during the contract negotiation process that “most [families] will readily embrace the opportunity to visit from home.”51 Securus did not offer any evidence, and our review of the record in other counties shows Securus scrambling to stimulate demand where it does not exist,52 frequently charging promotional rates well below the prices in the contracts and for far longer than the promotional period described in the contracts.53

- Total visitation will go up? Although families dispute the assumption, sheriffs argue that video visitation is equivalent to in-person visitation, and they are quick to assert that since video visitation is more efficient, visitation will increase. For example, Travis County, Texas Jail Administrator Darren Long told the County Commissioners Court that video visitation has allowed the jails to provide an additional 11,000 visits.54 In reality, the number of visits in Travis County has declined. In September 2009, there were 7,288 in-person visits in Travis County jails.55 In September 2013 — a few months after in-person visits were completely banned — there were 5,220 visits. Rather than increase, the total number of visits decreased by 28% after the imposition of video visitation because families are unhappy with both free, onsite video visits and the paid, offsite video visits.56

- Most prisons and jails are moving to video visitation? The Travis County Jail Administrator Darren Long also asserted that video visitation “is best practices going across the nation right now”57 and implied that Travis County would be terribly behind if it did not adopt video visitation. In reality, only 12% of the nation’s 3,283 local jails have adopted video visitation.58 Administrator Long showed a slide with a list of 19 states that use video visitation, but, as discussed earlier, most state prison systems are using video conferencing and video visitation59 on a very small scale as a supplement to existing visitation and certainly never as the dominant form of visitation.60

- Video visitation will reduce long lines? Unlike traditional visitation, many video systems require families to schedule both onsite and offsite video visits at least 24 hours in advance. Many families find coordinating issues like transportation to the jail, childcare, and employment difficult, so requiring visits to be scheduled discourages people from attempting drop-in visits. To their credit, many facilities with policies requiring visits to be scheduled in advance appear to allow drop-in visits when possible, but this leads to confusion when there are even longer waits for a video visit than under the traditional system.61

- Remote video visitation is convenient? The promise of video visitation is that it will be easier for families, but these systems are very hard to use. In our experience doing remote video visits and in our interviews with family members, the most common complaint — even from people who claim to be comfortable with computers — is that these systems are inconvenient.62 We heard of and experienced repeated problems getting pictures of photo IDs to companies,63 scheduling visits, processing payments, and with some companies not supporting Apple computers.64 Today in 2015, virtually every other internet-based company has made it easy for consumers to purchase and pay for their products, but the video visitation industry — perhaps because of its exclusive contracts — apparently has little desire to win customer loyalty through making its service easy to use.

The financial incentives in the video visitation market put the priorities of the companies before the facilities or the families, so it should come as no surprise the industry is not able to meet all of its attractive promises. Because video visitation is often framed as an “additional incentive” in phone or commissary contracts rather than a stand-alone product, it is unclear how much thought and planning the companies and facilities put into the actual performance of these systems.65 The true end-users of this service — the families — are the ones who are served last. Worse still, these “add-ons” create spill-over effects, pushing their bloated costs onto other parts of the contract.

How are Securus video contracts different from other companies?

While most jails choose to ban in-person visitation after installing a video visitation system, only Securus contracts explicitly require this outcome. The Securus contracts also tend to go further with detailed micromanagement of policy issues that would normally be decided upon by elected and appointed correctional officials.

It is common to find the following elements in Securus contracts:

- “For non-professional visitors, Customer will eliminate all face to face visitation through glass or otherwise at the Facility and will utilize video visitation for all non-professional on-site visitors.”

- “Customer will allow inmates to conduct remote visits without quantity limits other than for punishment or individual inmate misbehavior.” Apparently, Securus does not think that the profit share is enough of an incentive for facilities to encourage the use of offsite video visits.

- Additionally, Securus specifies that the county must pay for any free sessions the county wants to provide. With this clause and clauses that “reduce the on-site visitation hours over time,”66 Securus is restricting free, onsite visits and pushing families toward paid, remote visits.

- Securus specifies how and where the incarcerated population may move in the facility, with a requirement that the terminals be available “7 days a week, 80 hours per terminal per week.”67

Most of the other contracts we reviewed do not require specific correctional policies or changes. One company TurnKey Corrections has clauses in its contracts that are almost the opposite of those of Securus’s such as:

- “Provider wishes to minimize fees charged to inmate’s family and friends and allow revenue and efficiency to grow thus providing the County the maximum amount of revenue possible.”

- “Privileges may be revoked and suspended at any time for any reason for any user.” While communication between incarcerated people and their families should be encouraged, correctional facilities should be responsible for setting visitation policies, not private companies.

- “The communication of changes will be done a minimum of 15 days in advance of the change. Provider warrants to change prices no more than 3 times annually.”

The way jails typically implement video visitation systems violates correctional & policy best practices

With few exceptions, jail video visitation is a step backward for correctional policy because it eliminates in-person visits that are unquestionably important to rehabilitation while simultaneously making money off of families desperate to stay in touch. In fact, banning in-person visits and replacing them with expensive virtual visits runs contrary to both the letter and the spirit of correctional best practices as defined by the American Correctional Association (ACA), the nation’s leading professional organization for correctional officials and the accreditation agency for U.S. correctional facilities.

In four conferences going back to 2001,68 the ACA has consistently declared that “visitation is important” and “reaffirmed its promotion of family-friendly communication policies between offenders and their families.”69 According to the ACA, family-friendly communication is “written correspondence, visitation, and reasonably-priced phone calls.”70 The ACA believes that, in addition to visitation, correctional facilities should provide incarcerated people other forms of communication. In its 2001 policy on access to telephones, the ACA states that, while “there is no constitutional right for adult/juvenile offenders to have access to telephones,” it is “consistent with the requirements of sound correctional management” that incarcerated people have “access to a range of reasonably priced telecommunications services.”71

Yet, instead of being used as a supplemental telecommunications service, jails are frequently using video visitation to replace in-person visitation. Jail video visitation systems are further against correctional best policy because:

- The ACA is explicit that it “supports inmate visitation without added associated expenses or fees.” In the video visitation industry, visitation — which has long-been provided for free — now has a price tag. Most jails provide a minimum number of onsite video visits for free, but sometimes facilities and companies make it nearly impossible for families to utilize these free visits. In Washington County, Idaho, families are given two free visits per week, but these visits can only be used from 6-8am.72 Other counties are even more restrictive and in direct violation of the ACA resolution. Lincoln County, Oregon and Adams County, Mississippi left families with only one option to visit: paid, offsite video visits.73 Portsmouth County, Virginia, which has offsite and onsite video visitation, goes as far as to charge for both.74

- The ACA defines reasonably priced as “rates commensurate with those charged to the general public for like services.”75 And, while sheriffs are usually quick to compare video visitation to services like Skype and FaceTime, those services are free. Video visitation, on the other hand, can cost over $1 per minute. In Racine County, Wisconsin, a 20-minute video visit costs $29.95.76

Similarly, the American Bar Association (ABA), the nation’s largest association of lawyers, foresaw that facilities would use new technologies to abolish in-person visitation, so it urged in its 2010 criminal justice standards: “Correctional officials should develop and promote other forms of communication between prisoners and their families, including video visitation, provided that such options are not a replacement for opportunities for in-person contact.”77

Notably, state prison officials are already in full compliance with this ABA recommendation, as the state prison officials who have considered video visitation understand the harm that would result from implementing video visitation systems as jails do.78 Illinois Department of Corrections spokesman Tom Shaer told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “All research shows in-person visits absolutely benefit the mental health of both parties; video can’t match that.”79

Further, the editorial boards of papers as diverse as Austin American-Statesman, The Dallas Morning News, Houston Chronicle, The New York Times, and The Washington Post have severely criticized jail video visitation systems80 for weakening family ties and preying on those least able to afford another expense. A clear and strong national consensus has developed that jail video visitation systems are a major step in the wrong direction.

Video visitation can be a step forward

Much of this report has focused on the way that video visitation is implemented by the largest companies in the industry, arguing that it is a significant step backwards for families and public safety. But video visitation done differently could be a major step forward, and some companies are already taking some of these steps. For example, the data shows that it is economically beneficial to preserve existing visitation systems, and there are ways to operate a video visitation system that actually make visitation more convenient for families.

Two of the industry leaders, Securus and Telmate, claim that in order to be economically viable, they must ban in-person visitation, but some of their competitors have found other, more reliable ways to stimulate demand. Securus and Telmate are utilizing a strategy that is proven by their competitors to be penny-wise and pound-foolish.

Securus almost always requires facilities to ban in-person visitation and justified this to Dallas County, Texas saying that the “capital required upfront is significant and without a migration from current processes to remote visitation, the cost cannot be recouped nor can the cost of telecom be supported.”81 Similarly, Telmate’s CEO says that banning in-person visits is the only way to increase video visitation volume in order to recoup Telmate’s investment.82

However, TurnKey Corrections has found that when facilities offer families more and better visitation options, families will use remote video visitation more. TurnKey found:83

- When traditional, through-the-glass visits are retained, the jail averages 23 minutes of offsite video visits per month per incarcerated person.

- When through-the-glass visits are replaced with onsite video visits, the jail averages 19 minutes of offsite video visits per month per incarcerated person.

- When offsite video visits are the only visitation option, the jail averages only 13 minutes of offsite video visits per month per incarcerated person.84

Turnkey’s experience is that the best way to sell offsite video visitation is to use other forms of visitation to build the demand. Putting up barriers to visitation does little besides discourage families from trying the company’s paid service.85

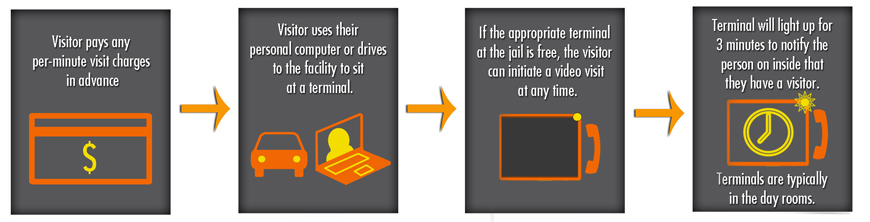

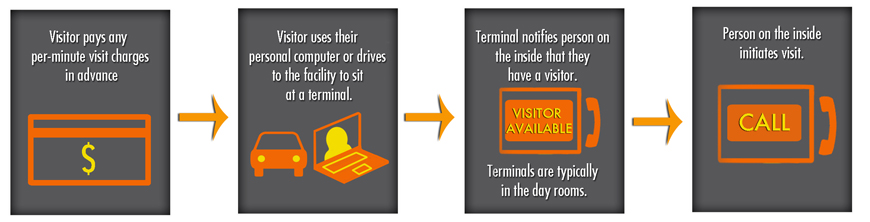

Two companies, Turnkey and HomeWAV, structure their systems differently than the market leaders and structure them more like phone services. Both charge per minute rather than per visit, and neither company requires families to pre-schedule video visits:

Figure 9. TurnKey charges per minute and allows the visitor to call into the facility without an appointment.

Figure 9. TurnKey charges per minute and allows the visitor to call into the facility without an appointment.

Figure 10. HomeWAV charges per minute and does not require appointments. The visitor says when he or she is available, and then the person on the inside makes an outgoing video call.

Figure 10. HomeWAV charges per minute and does not require appointments. The visitor says when he or she is available, and then the person on the inside makes an outgoing video call.

HomeWAV told us that the average length of a visit on their system is 5.79 minutes, significantly fewer than the standard visit blocks of 20 or 30 minutes. By charging per minute, families are incentivized to use video visits for shorter time periods. For example, it is possible for a daughter to say goodnight to her incarcerated father or for a husband to ask his wife if she received her commissary money via video visit, without the visit being financially burdensome.

While some families find being able to schedule a video visit superior to waiting in a long line for an unscheduled visit, adding the option for unscheduled visits has other advantages including:

- It would be better than the telephone because it would allow family members to decide when to communicate, rather than being forced to sit and wait by the telephone.

- It makes per-minute pricing both possible and efficient for both families and the companies.

Additionally, some companies have prioritized supporting their customers and whatever computing devices they have and want to use. For example, HomeWAV reports that 60% of its visits are done using their HomeWAV Android or iPhone/iPad application. By contrast, some other companies do not even support Apple computers.

| Company | Microsoft only? | Mobile/tablet application? |

|---|---|---|

| HomeWAV | No | Yes |

| ICSolutions / VizVox | Yes | No |

| JPay | No | Yes |

| Renovo | Not anymore | Only for scheduling |

| Securus | Yes | No |

| Telmate | No | Coming soon |

| TurnKey Corrections | No | Yes |

Making video visitation more convenient is the key to increasing demand, and with higher demand, the companies can lower prices, which will further stimulate demand.

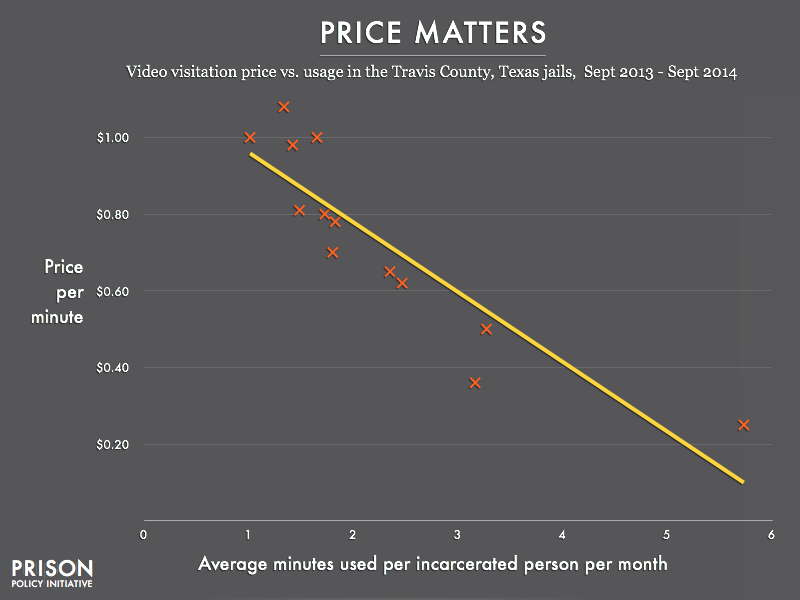

In the facilities that contract with HomeWAV, which typically charges $0.50 per minute, the average video visitation usage is 16 minutes per incarcerated person per month. By contrast, we found that the average usage of Securus video visitation in Travis County, Texas from September 2013 to September 2014 was 2 minutes per incarcerated person per month.86 Further, our analysis of the volume and pricing data in Securus’s commission reports for Travis County found clear evidence that pricing matters:

Figure 12. Video visitation price vs. usage in Travis County, Texas jails.

Figure 12. Video visitation price vs. usage in Travis County, Texas jails.

The lesson is clear: the current approach to jail video visitation from Securus and other large companies is not effectively stimulating demand. While companies and facilities could make many small and large changes to address the lack of demand, the companies should start by giving up on the failed idea that banning in-person visitation is the only way to stimulate demand.

Recommendations

The rapid rise of the video visitation industry has received shockingly little attention, especially given the potential for this technology to serve as an end-run around existing FCC regulation. Right now, while the service is still new and evolving, we have a unique opportunity to shape the future of this industry; lest its worst practices become entrenched as standard procedure. While this report identifies some clear negative patterns — namely the frequency by which jails ban in-person visitation after adopting this technology — the diversity of practices in this market gives us hope that video visitation could be positive for both facilities and families.

The Federal Communications Commission should:

- After regulating both in-state telephone call rates and the unreasonable fees charged by the prison and jail telephone companies, the FCC should regulate the video visitation industry so that the industry does not shift voice calls to video visits. The proposed regulations should build on comprehensive phone regulations to include rate caps for video visitation.

- Prohibit companies from banning in-person visitation. The FCC should require companies, as part of their annual certification, to attest that they do not require any of their contracting facilities to ban in-person visitation. This requirement would not stop the sheriffs from taking such a regressive step on their own, but it would be a powerful deterrent.

- Prohibit the companies from signing contracts that bundle regulated and unregulated products together. Requiring that facilities bid and contract for these services separately would end the current cross-subsidization. Alternatively, the FCC could strengthen safeguards when allowing the bundling of communications services in correctional facilities, to ensure that the facilities are better able to separately review advanced communications services as part of the Request for Proposals process. Either approach needs to enable all stakeholders to understand these services, their value, and the financial terms of the contracts.

- Consider developing minimum quality standards of resolution, refresh rate, lag, and audio sync for paid video visitation. We note that JPay’s official bandwidth requirements are extremely low, and that in our test the facility struggled to provide even that bandwidth. The FCC could collect comments that review the academic literature on the appropriate thresholds for effective human video communication and devise appropriate standards.

- Require family- and consumer-friendly features such as charging per-minute rather than per visit. As the experiences of TurnKey and HomeWAV demonstrate, not every conversation needs to take the same amount of time. It is both fairer and more conducive to greater communication to charge for actual usage.

State regulators and legislatures should:

- Immediately catch up and implement regulations like those of the Alabama Public Service Commission that actively regulate not only the prison and jail telephone industry but also these companies’ video visitation products.87

- Statutorily prohibit county jails from signing contracts that ban in-person visitation. These statutes should recognize that video visitation is a potentially useful supplement to existing visitation systems, but never a replacement.88 Further, while facilities routinely restrict visitation as part of their disciplinary procedures, such internal rules have no place in a contract with a telecommunications provider.

Correctional officials and procurement officials should:

- Explicitly protect in-person visits and treat video only as a supplemental option. Social science research and correctional best practices, as put forth by the American Correctional Association and the American Bar Association, encourage visitation because it is crucial to preventing recidivism and facilitating successful rehabilitation. Video could be beneficial as an additional option for communication, but facilities should ensure that they do not approve video contracts that will later lead to the banning of in-person visits.

- Refuse commissions. Commissions drive up the cost to families which leads directly to lower communication. Particularly when introducing new services like video visitation, facilities should resist the penny-wise and pound-foolish temptation provided by commissions.

- Scrutinize contracts for expensive bells and whistles that facilities do not want or need. Insist on removing these items and instead having the rates lowered or, if they choose to receive a commission, having that commission increased.

- When putting in video visitation systems, put some thought in to where the terminals are located so as to maximize privacy. Existing visitation systems allow for monitored but otherwise private conversations, but putting video visitation terminals into busy pods of cells and day rooms can reduce the benefits of a family visit.

- Refuse to sign contracts that give private companies control over correctional decisions, including visitation schedules, when it is acceptable to limit an incarcerated person’s visitation privileges, or the ability of people in correctional custody to move within the facility.

- Refuse to sign contracts that bundle multiple services together. Contracts for one service that contain a discount because of other contracts are fine, but bundling multiple services together makes it impossible to determine whether you are getting a good deal.

- Consider the benefits of providing incarcerated people a minimum number of free visits per month. This minimal investment could reap large dividends for families and for reducing recidivism.

- Invite bids where the facility purchases equipment from the companies instead of requiring that all bids be submitted on a no-cost basis.89 Having the company finance the equipment and installation just increases the costs to families and cuts into any commission the facility chooses to receive.

- Experiment with regional video visitation centers for your state prison system and remote jails. Regional centers serve as a great supplement to existing visitation systems. The centers operated by the Virginia Department of Corrections could serve as a possible model.

- Insist on contracts where companies list and justify not just the cost of each video visit, but all fees to be charged to families. Lowering the fees keeps more money in families’ pockets, making it easier for them to use the video visitation system more. This will have positive results both for reducing recidivism and also for any commission that the facility chooses to receive. For examples of questions that should be asked of prospective companies and evidence that such questions can bring about significant decreases in fees, see Securus’s response to such questions as part of the Request for Proposals process in Dallas, Texas.90

- If the facility allows the company to install any terminals for onsite visitation use by visitors, do not neglect basic issues like privacy partitions between the terminals and height-adjustable seats so that children and adults of various heights can see the screen and be visible on camera.

Companies should:

- Improve the product so that people will choose to use it even when they are not being forced to do so. Areas of improvement include cost, video quality, usability of websites, streamlining the reservation process, and improving customer support.

- Experiment with ways to market the products that are more creative than banning in-person visitation. Encouraging facilities to maintain traditional visitation — as TurnKey’s experience has shown — increases demand for offsite visitation products.

- Take advantage of existing technology to improve eye contact for video visits. Specifically, reduce the vertical distance between the camera and the screen and experiment with integrating the camera behind the screen of onsite terminals. The basic technology for this already exists. For example, the Prison Policy Initiative purchased a $50 device that mounts over a webcam that repositions the on-screen video, allowing us to look directly into the lens while also seeing the people we are doing remote presentations with.91

- Support more operating systems and mobile devices. JPay, HomeWAV, and TurnKey Corrections support mobile devices, Renovo only added support for Apple computers in late 2014, and Securus and ICSolutions still do not support Apple computers.

- Experiment with allowing incoming video visits without an appointment. Most prisons and jails do not require appointments for traditional visits and TurnKey and HomeWAV’s video visitation systems do not require appointments either.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible by the passion of hundreds of people for a fair communications system. This report was supported by the Returning Home Foundation, by the individual donors who invest in our work so that we can take on critical emerging issues like video visitation, and by the American Constitution Society David Carliner Public Interest Award awarded to Peter Wagner in June 2014. We are grateful for the research assistance provided by family members, incarcerated people, and company officials who answered questions and shared their experiences, for Eric Lotke’s and Dee Ann Newell’s support with open records requests in their states, and for Brian Dolinar’s and Jorge Renaud’s invaluable research that they chose to share with us. We could not have developed effective ways to illustrate the human cost of video visitation without the fresh ideas of Elydah Joyce, Jazz Hayden, and Mara Lieberman. Jazz Hayden generously modeled for the cover image and Figures 3 and 4; Elydah Joyce drew Figures 1, 9, and 10 and took the cover photograph. Throughout the research and drafting process, our colleagues Aleks Kajstura, Drew Kukorowski, and Leah Sakala offered invaluable feedback and assistance.

We dedicate this report to the people of Dallas County, Texas, who showed that it is possible to stand up to a video visitation giant and reject a contract that would have banned in-person visitation.

About the authors

Bernadette Rabuy is a Policy & Communications Associate at the Prison Policy Initiative and a 2014 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley. Her previous experience includes work with the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, Voice of the Ex-Offender, and Californians United for a Responsible Budget.

Peter Wagner is an attorney and the Executive Director of the Prison Policy Initiative and a co-author of the Prison Policy Initiative’s oft-cited expose Please Deposit All of Your Money: Kickbacks, Rates, and Hidden Fees in the Jail Phone Industry.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to challenge over-criminalization and mass incarceration through research, advocacy, and organizing. We show how the United States’ excessive and unequal use of punishment and institutional control harms individuals and undermines our communities and national well-being. The Easthampton, Massachusetts-based organization is most famous for its work documenting how mass incarceration skews our democracy and how the prison and jail telephone industry punishes the families of incarcerated people. The organization’s groundbreaking reports and its work with SumOfUs to collect 60,000 petitions for the Federal Communications Commission have been repeatedly cited in the FCC’s orders.

Exhibits

Footnotes

*Family members’ names have been changed throughout the report.

In criminal justice expert Joan Petersilia’s book, When Prisoners Come Home, Petersilia says, “Every known study that has been able to directly examine the relationship between a prisoner’s legitimate community ties and recidivism has found that feelings of being welcome at home and the strength of impersonal ties outside prison help predict postprison adjustment.” Joan Petersilia, When Prisoners Come Home (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006), p 246. Milwaukee County Sheriff David A. Clarke Jr. has said that a functioning video visitation system is important “because caring attachment matters in human interactions.” Steve Schultze, “County jail visitations limited to audio only after system breaks down,” Journal Sentinel, January 23, 2014. Accessed on January 6, 2015 from: http://www.jsonline.com/news/milwaukee/county-jail-visitations-limited-to-audio-only-after-system-breaks-down-b99190707z1-241732571.html. ↩

Minnesota Department of Corrections, The Effects of Prison Visitation on Offender Recidivism (St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Corrections, November 2011), p 27. Accessed on December 3, 2014 from: http://www.doc.state.mn.us/pages/files/large-files/Publications/11-11MNPrisonVisitationStudy.pdf . ↩

Quote from Richard Brown, Rockville Correctional Facility’s assistant superintendent, in Jessica Gresko, “Families visit prison from comfort of their homes,” CorrectionsOne, July 2, 2009. Accessed on October 22, 2014 from: http://www.correctionsone.com/products/corrections/articles/1852337-Families-visit-prison-from-comfort-of-their-homes/ . ↩

Chesa Boudin, Trevor Stutz, and Aaron Littman, “Prison Visitation Policies: A Fifty State Survey” Yale Law & Policy Review Vol 32:149 (March 2014), 149-189. ↩

On the other hand, it is also not possible to transmit contraband through the glass partition typically used in county jails either. ↩

The Bureau of Justice Statistics conducted personal interviews of 521,765 people incarcerated in state prisons in 1991 and found that 86% of those interviewed had an annual income less than $25,000 after being free for at least a year. Allen Beck et al., Survey of State Prison Inmates, 1991 (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics, March 1993), p 3. Accessed on January 5, 2015 from: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/SOSPI91.PDF. Bruce Western found that about a third of incarcerated individuals were not working when they were admitted to prison or jail. Bruce Western, “Chapter 4: Invisible Inequality,” in Punishment and Inequality in America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006), p 85-107. Tom Miriam from Global Tel*Link explained to Dallas County Commissioners why Securus’s video visitation usage projections are unreasonably high, saying, “This demographic doesn’t have high-speed internet and credit cards.” The County of Dallas, “Dallas County Commissioners Court,” The County of Dallas Website, September 9, 2014. Accessed on January 6, 2015 from: http://dctx.siretechnologies.com/sirepub/mtgviewer.aspx?meetid=177&doctype=AGENDA. ↩

According to a recent Census Bureau report, among households with income less than $25,000, 62% have a computer but only 47% have high-speed internet. Thom File and Camille Ryan, Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2013 (Washington, D.C.: United States Census Bureau, November 2014), p 3. Accessed on November 2014 from: http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/acs/acs-28.pdf?eml=gd&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery . ↩

Clair Beazer, “Video Visitation,” The Real Cost of Prisons Project, March 25, 2008. Accessed on October 11, 2014 from: http://realcostofprisons.org/writing/beazer_video.html. ↩

We identified the facilities with video visitation by reviewing the companies’ websites, hundreds of news articles, and interviews with facilities and companies. For the list, see Exhibit 1. ↩

In Professor Patrice A. Fulcher’s analysis of video visitation, Fulcher talks about the lack of centralized data. Patrice Fulcher, “The Double Edged Sword of Prison Video Visitation: Claiming to Keep Families Together While Furthering the Aims of the Prison Industrial Complex” Florida A&M University Law Review Vol 9:1:83 (April 2014), 83-112. A New York Times article states that there were hundreds of jails in at least 20 states using or planning to adopt video visitation systems at that time. Adeshina Emmanuel, “In-Person Visits Fade as Jails Set Up Video Units for Inmates and Families,” The New York Times, August 7, 2012. Accessed on December 1, 2014 from: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/07/us/some-criticize-jails-as-they-move-to-video-visits.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 . Other excellent pieces on video visitation have been done by The Sentencing Project and The University of Vermont: Susan D. Phillips, Ph.D., Video Visits for Children Whose Parents Are Incarcerated: In Whose Best Interest? (Washington, D.C.: The Sentencing Project, October 2012). Accessed on October 11, 2014 from: http://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/video-visits-for-children-whose-parents-are-incarcerated-in-whose-best-interest/. and Patrick Doyle et al., Prison Video Conferencing (Burlington, VT: The University of Vermont James M. Jeffords Center’s Vermont Legislative Research Service, May 15, 2011). Accessed on December 2014 from: https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/Department-of-Political-Science/vlrs/New%20folder/prison_video_conferencing.pdf . ↩

Boudin, Stutz, and Littman, 2014, p 179. A report by Grassroots Leadership found that four states collectively send more than 10,000 prisoners to out-of-state private prisons. For the report, see: Holly Kirby, Locked Up & Shipped Away: Paying the Price for Vermont’s Response to Prison Overcrowding (Austin, TX: Grassroots Leadership, December 2014). Accessed on January 9, 2015 from: http://grassrootsleadership.org/sites/default/files/reports/locked_up_shipped_away_vt_web.pdf. ↩

State prison programs that are operated on a small scale and are specifically for incarcerated parents include Florida’s Reading and Family Ties program, New Mexico’s Therapeutic Family Visitation Program, and New York’s program with the Osborne Association. According to Boudin, Stutz, and Littman, 2014, p 171, the following are other states using video visitation in a limited scope: Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Ohio. ↩

See Exhibit 2: New Mexico Corrections Department Contract with PB&J Family Services. ↩

The states that use video conferencing for hearings include: Michigan, Minnesota, and New Jersey. ↩

We are using the term “regional video visitation center” to describe situations where the state has made an effort to bring visitation to the visitors. For example, we consider having special places throughout the state or using a mobile van (Pinellas County, Florida) to be regional visitation centers, but we would not consider Maricopa County, Arizona’s decision to make onsite video visitation terminals available at two of the county’s six jails to be regional visitation. ↩

Paul Hampel, “Video visits at St. Clair County Jail get mixed reviews,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 20, 2014. Accessed on December 22, 2014 from: http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/crime-and-courts/video-visits-at-st-clair-county-jail-get-mixed-reviews/article_b46594b0-9f01-5987-abf0-83152f76c9dd.html . ↩

According to Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, of the 722,000 people in local jails, almost 300,000 are serving time for minor offenses. See Peter Wagner and Leah Sakala, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie (Easthampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, March 12, 2014). Accessed on December 2014 from: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie.html. ↩

As Sheriff Dotson of Lincoln County told The Oregonian, “There’s not much of a difference [between video and through-the-glass visitation] — shatterproof glass divides the visitor from the inmate at the jail and they talk by phone.” Maxine Bernstein, “Video visitation coming soon to Multnomah County jails,” The Oregonian, October 3, 2013. Accessed on October 27, 2014 from: http://www.oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2013/10/video_visits_coming_soon_to_mu.html. The second-in-command at the Knox County, Tennessee detention center, Terry Wilshire, has also said that video visitation is almost the same as in-person, through-the-glass visits: “It’s a standing booth, it’s cold, it’s got that big glass there —there’s no more contact with a child there [than with a video].” Cari Wade Gervin, “Orange Is the New Green: Is Knox County’s New Video-Only Visitation Policy for Inmates Really About Safety—or Is it About Money?,” Metro Pulse, July 2, 2014. Accessed on September 2014 from: http://www.metropulse.com/news/2014/jul/02/orange-new-green-knox-countys-new-video-only-visit/. ↩

Robert McCoppin, “Video visits at Illinois jails praised as efficient, criticized as impersonal,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 2014. Accessed on October 6, 2014 from: http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2014-01-12/news/ct-jail-video-visits-met-20140112_1_inmates-and-visitors-video-visitation-john-howard-association . ↩

Chase Hoffberger, “Through a Glass, Darkly,” The Austin Chronicle, November 7, 2014. Accessed on November 8, 2014 from: http://www.austinchronicle.com/news/2014-11-07/through-a-glass-darkly/ . ↩

Hampel, 2014. ↩

Peter Hermann, “Visiting a detainee in the D.C. jail now done by video,” The Washington Post, July 28, 2012. Accessed on November 10, 2014 from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/crime/visiting-a-detainee-in-the-dc-jail-now-done-by-video/2012/07/28/gJQAcf1TGX_story.html. ↩

Hampel, 2014. ↩

Dee Ann Newell told the Prison Policy Initiative that she once had to take a child to the ER due to a traumatic video visit. For another example, see this video testimony of a grandmother from the January 21, 2014 Travis County Commissioners Court at 1:24:30: Travis County, “Travis County Commissioners Court Voting Session,” Travis County Website, January 21, 2014. Accessed on December 2014 from: http://traviscountytx.iqm2.com/Citizens/Detail_Meeting.aspx?ID=1387. ↩

Jennifer Sullivan, “King County to install video system in jails for virtual inmate visits,” The Seattle Times, June 17, 2014. Accessed on October 2014 from: http://seattletimes.com/html/latestnews/2023866693_jailphonesxml.html. ↩

San Francisco Children of Incarcerated Parents, “Right 5,” San Francisco Children of Incarcerated Parents Website. Accessed on November 2014 from: http://www.sfcipp.org/right5.html. ↩

We interviewed a handful of families and friends nationwide to hear about their firsthand experiences with video visitation. Jessica* has used Securus video visitation in Travis County, Texas, and Sara* has used Securus video visitation in Maricopa County, Arizona. ↩

Annalise Little, “Home video chats, other upgrades coming to CCDC,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, October 13, 2014. Accessed on October 13, 2014 from: http://www.reviewjournal.com/news/las-vegas/home-video-chats-other-upgrades-coming-ccdc . ↩

For the Bureau of Justice Statistics study based on surveys of people incarcerated in state prisons, see: Beck et al., 1993, p 3. Additionally, the Census Bureau found that only 47% of households with income less than $25,000 have high-speed internet. File and Ryan, 2014, p 3. ↩

Editorial Board, “Idea blackout,” Houston Chronicle, September 12, 2014. Accessed on September 12, 2014 from: http://www.houstonchronicle.com/opinion/editorials/article/Idea-blackout-5752156.php . ↩

The one state prison exception that uses video visitation and bans in-person visitation, Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility in Wisconsin, considers itself to be very similar to a jail, writing on its website that it “functions in a similar manner to that of a jail operation.” See: Wisconsin Department of Corrections, “Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility,” Wisconsin Department of Corrections Website. Accessed on December 2014 from: http://doc.wi.gov/families-visitors/find-facility/milwaukee-secure-detention-facility . ↩

Responsibility for banning in-person visitation cannot solely be attributed to the companies, because we note that even the jails that manage their own video visitation systems (Lee County, FL; Martin County, FL; Cobb County, GA; Wapello County, IA; Cook County, IL; Lenawee County, MI; Olmsted County, MN; Northwest Regional Corrections Center, MN; Sherburne County, MN) use video as a replacement rather than a supplement to existing visitation. In Global Tel*Link’s reply to the Alabama Public Service Commission’s further order adopting revised inmate phone rules, it states, “The Commission seeks to review VVS contracts because it is ‘concerned’ that the contracts may contain provisions limiting face-to-face visitation at correctional facilities…These contracts are based upon the expressed needs of the correctional facilities. Correctional facilities have sole discretion to place limitations on face-to-face visitation at the facility…” Global Tel*Link seems to be implying that jails are the ones pushing to end in-person visitation. See Exhibit 3 for Global Tel*Link’s reply. For more on Securus’s role in banning in-person visits, see footnote 66. ↩

See Exhibit 4 for Chippewa County, Wisconsin’s Securus video visitation contract approval form. In Washington County, Oregon’s contract with Telmate for phone services and video visitation, the county even received a bonus of $30,000 over three years. See Exhibit 5 for the Washington County, Oregon contract. ↩

For Telmate’s justification of its commissary account deposit fees, see page 10 of the Washington County, Idaho contract with Telmate. See Exhibit 6. ↩

We have seen examples of facilities starting off with video as a supplement to in-person visits but then banning in-person visits shortly after the video system was in place. Pinal County, Arizona launched video visitation in April 2013 as a supplement, and saw substantial use of both video and traditional visitation. But by December 2014, Pinal County had banned traditional visitation. JJ Hensley, “MCSO to allow video jail visits - for a price,” The Arizona Republic, December 10, 2013. Accessed on December 17, 2014 from: http://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/20131206mcso-to-allow-video-jail-visits-price.html and Bernadette Rabuy interview with Pinal County Sheriff’s Office on December 17, 2014. ↩

For the costs of the Dallas County video visitation system, see page 18 of the approved Dallas County contract with Securus. See Exhibit 7. ↩

As the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) notes, in the phones market, “site commission payments… inflate rates and fees, as ICS providers must increase rates in order to pay the site commissions.” See: Federal Communications Commission, Second Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, WC Docket No. 12-375 (Washington, D.C.: Federal Communications Commission, Released October 22, 2014), at ¶ 3. Accessed on January 8, 2015 from: http://www.fcc.gov/document/fcc-continues-push-rein-high-cost-inmate-calling-0 . ↩

For more information on the prison and jail phone industry’s fees, see Drew Kukorowski et al., Please Deposit All of Your Money: Kickbacks, Rates, and Hidden Fees in the Jail Phone Industry (Easthampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, May 8, 2013). Accessed on October 2014 from: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/phones/pleasedeposit.html. Phone company NCIC also produced an informational video on fees, which can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S3iB0p49oZ8 ↩

The highest commission on video charges we have seen — out of the contracts we gathered — is in Placer County, California where ICSolutions sends 63.1% back to the sheriff. In our 2013 report on the phones industry, ICSolutions also provided the highest commission, 84.1% of phone revenue. For Placer County’s contract with ICSolutions, see Exhibit 10. For more on phones, see Kukorowski et al., 2013. ↩

Federal Communications Commission, 2014, at ¶ 83. ↩

See Exhibit 12 for Securus’s response to the Maricopa County, Arizona Request for Proposals for video visitation. ↩

The Grassroots Leadership and Texas Criminal Justice Coalition study states that there was an “overall increase of 54.28 percent in contraband cases May 2014 versus May 2012.” See: Jorge Renaud, Video Visitation: How Private Companies Push for Visits by Video and Families Pay the Price (Austin, TX: Grassroots Leadership and Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, October 2014), p 9. Accessed on October 16, 2014 from: http://grassrootsleadership.org/sites/default/files/uploads/Video%20Visitation%20%28web%29.pdf. ↩

Sullivan, 2014. ↩

Jessica Lipscomb, “A new way to visit inmates at Collier jails: video conferencing,” Naples Daily News, December 11, 2014. Accessed on December 11, 2014 from: http://www.naplesnews.com/news/crime/a-new-way-to-visit-inmates-at-collier-jails-video-conferencing_50634238. ↩

When Mary* tried to drop in for an unscheduled video visit at a Texas county jail, she asked jail staff for assistance. Since Securus requires that video visits be scheduled at least 24 hours in advance, jail staff had to decide if they would make an exception for Mary who flew in from out of state to see her brother. Another requirement of Securus video visitation is that visitors take a photo of their identification in order to set up an account. Laina* used her personal computer’s webcam to take a photo of her ID, but her request to open an account was denied citing a blurry ID photo. Laina then had to travel to the jail to have jail staff look at her ID in-person and do a manual override. ↩

See Exhibit 13 for the August 2014 earnings report for Charlotte County Jail, Florida. ↩

For example, in one Securus contract, the commission is based on the gross revenue per month. If the gross revenue per month is $5,001-$10,000, the commission is 0%. If the revenue is $10,001-$15,000, the commission is 20%. If the revenue is $15,001-$20,000, the commission is 25%. If the revenue is $20,001+, the commission is 30%. For the Collier County, Florida contract, see Exhibit 14. ↩

Tom Miriam of Global Tel*Link told the Dallas County Commissioners that it was unreasonable for Securus to propose to pay commissions only if the County achieves 1.5 paid visits per incarcerated person per month when “the national average is 0.5 visit per inmate per month.” See: The County of Dallas, September 9, 2014. ↩

In most Securus contracts, the video visitation terminals are valued at $4,000 each, ignoring the cost of installation and software. Therefore, the 184 terminals installed in Travis County are valued at $736,000, an immense sum compared to the $43,445 Securus earned from offsite video visitation in the period September 2013-September 2014. Either Securus is losing money on each video visit, or the terminals are overvalued in the contracts, or Securus is using phone revenue to subsidize the video business. For the Travis County contract, see Exhibit 15. For the commission data, see Exhibit 16. Additionally, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that St. Clair County, Illinois receives a 20% commission on video visits if it reaches 729 paid visitors a month, but there were only 388 in January 2014. See Hampel, 2014. ↩

Amy Silverstein, “Captive Audience: Counties and Private Businesses Cash in on Video Visits at Jails,” Dallas Observer, November 26, 2014. Accessed on November 28, 2014 from: https://www.dallasobserver.com/news/captive-audience-counties-and-private-businesses-cash-in-on-video-visits-at-jails-7110523 . ↩

For the Securus response to Dallas County’s additional best and final offer questions, see Exhibit 9. ↩

Securus is not the only company facing the reality of low demand for video visitation services. In Washington County, Oregon — which contracts with Telmate and uses video visitation as a supplement — the jail logged 86 video visits in September 2013. See Bernstein, 2013. We calculated — using the U.S. Census figure for the jail population of 197 — that the jail logged an average of 13 minutes per incarcerated person for that month. ↩

Securus is charging a promotional rate in 67% of the contracts we gathered for our sample. For instance, in Saunders County, Nebraska’s contract with Securus, a 30-minute offsite visit is priced at $30, but for “a limited time,” the promotional rate is $5 for a 35-minute visit. (See Exhibit 18 for the Saunders County contract.) In the Securus contract with Travis County, Texas, the contract specifies that all video visits should be charged at standard rates after the system has been installed for three months. However, Securus has rarely charged the standard rate in the year and a half following implementation. (See Exhibits 15 and 16) ↩

For the video of Darren Long’s testimony in Travis County Commissioners Court, see: Travis County, “Travis County Commissioners Court Voting Session,” Travis County Website, January 21, 2014. Accessed on December 2014 from: http://traviscountytx.iqm2.com/Citizens/Detail_Meeting.aspx?ID=1387. Travis County, 2014. ↩