by Peter Wagner,

October 19, 2013

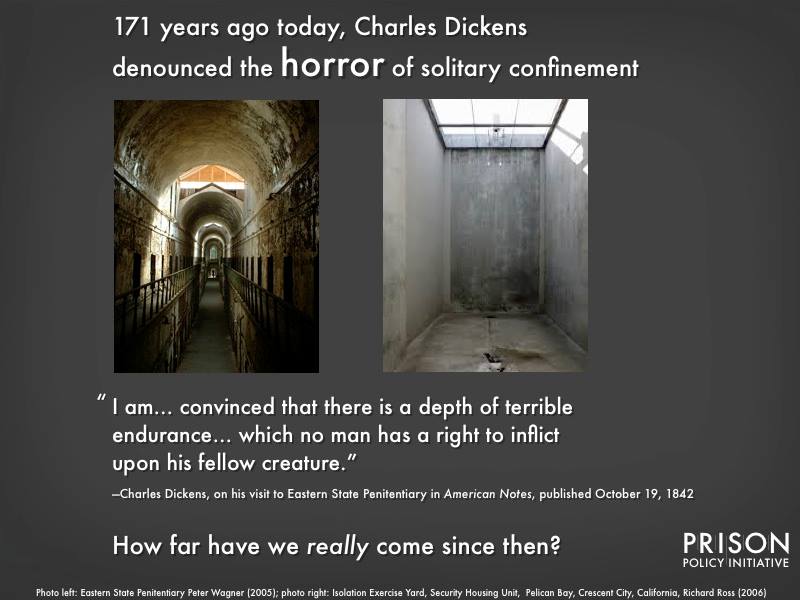

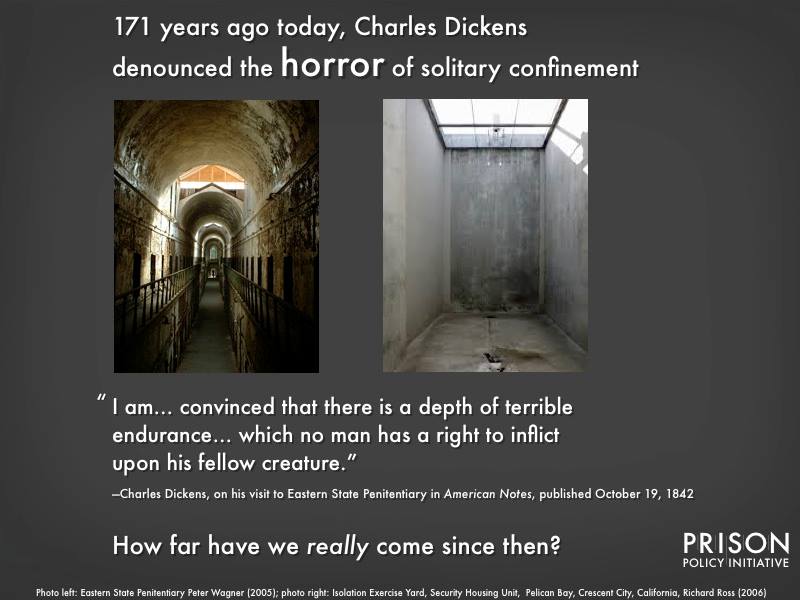

When Charles Dickens came to the United States, he wanted to see two things: Niagara Falls and Eastern State Penitentiary. He expected to be impressed with this radical new type of prison with a solitary confinement system. Instead, he was horrified. PPI’s Leah Sakala made this graphic to commemorate this anniversary:

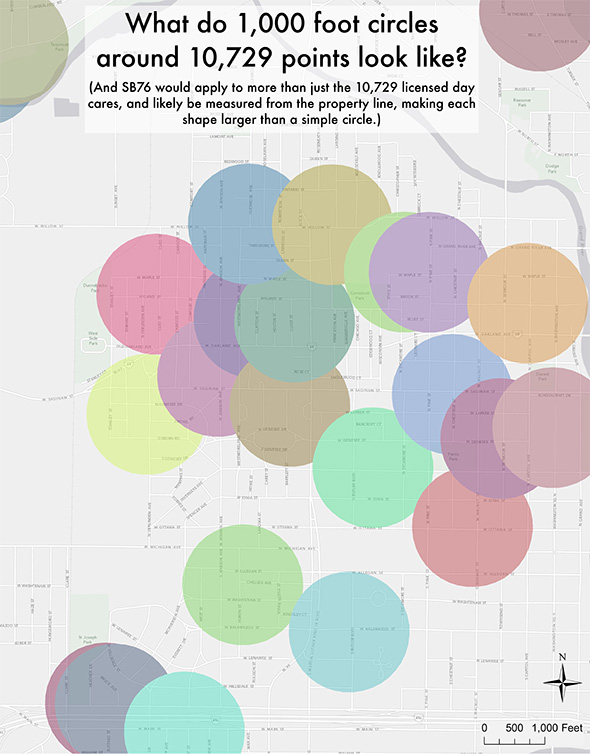

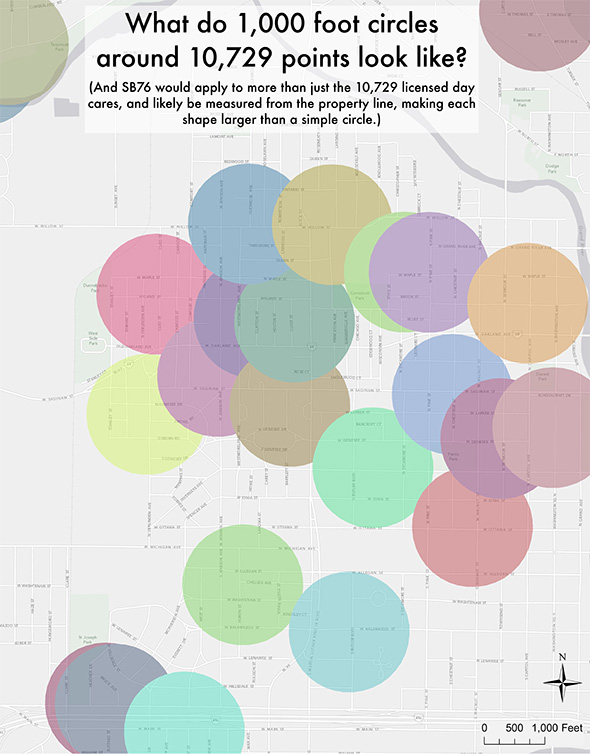

We produced a map to illustrate the ACLU’s testimony against a counterproductive zone law.

by Peter Wagner,

October 17, 2013

The Michigan ACLU testified yesterday against a bill proposing counterproductive and ineffective restrictions on where people on the sex offender registry would be allowed to “loiter”. This bill would expand the current restrictions to also include all areas within 1,000 feet of a day care center, creating “a nearly impossible burden on listed offenders and on law enforcement.” Here at the Prison Policy Initiative, we produced a map to illustrate the ACLU’s testimony by demonstrating that the simple-sounding law would blanket dense urban areas with a confusing pattern of imperceptible zones.

Our map showing that most of the Michigan capital city of Lansing is within 1,000 feet of just two dozen of the 10,729 day care centers in the state.

Litigator Kung Li stopped by our office in August to talk about her experience working with us on the Southern Center for Human Rights’ Whitaker v. Perdue case.

We’ve also prepared similar analysis for court cases in Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts and elsewhere. This work grew out of our research on sentencing enhancement zones, the drug laws that give enhanced penalties based on where an offense occurs, not on its dangerousness. These laws are all too common, and the basic differences are the number of protected places, the distances involved, and how that distance is to be measured.

In all the cases we’ve looked at, a few key points about geography and geometry keep coming back:

- Drawing large circles around thousands of places blankets entire cities in “protected” or “off-limits” areas.

- Doubling the distance in one of these statutes makes the protected area four times as large (remember pi r squared?).

- 1,000 feet — and most distances, for that matter — are actually much further than most people assume.

- Laws that measure the distance as the crow flies extend coverage to areas that are, for all practical purposes, very far away.

- Laws that measure the distance on a property line-to-property line basis cover considerably more area than simple 1,000 foot circles drawn around the center point of a particular property.

Most importantly, however, the laws that fail to work as intended share the same fundamental flaw of covering too much area. This might sound like it would produce more safety but it actually produces less for the simple reason that when you make everywhere special, nowhere is special.

Alabama Public Service Commission caps phone rates and limits fees charged for phone calls from correctional facilities.

by Aleks Kajstura,

October 9, 2013

In a sweeping proposal to rein in the exorbitant costs of calls to people in jails and prisons, the Alabama Public Service Commission seeks to cap all call rates and place strict limits on fees and other charges. We are particularly happy to see this comprehensive proposal addresses fees because, as we explain in our recent report, we found that fees account for 38% of the money spent on calls from correctional facilities.

The proposed rules seek to cap calls at $0.25 per minute, and video visitation at $0.50 per minute, noting that “[a]ffordable VVS [Video Visitation Service] rates are in the best interests of Alabama inmates, their families, and the confinement facilities.” (Video visitation still accounts for only a small part of communication with family members in jail and prison, but this cap is an important component of regulation because video visitation is a quickly growing service.)

We have previously identified commissions paid to correctional facilities as a major factor in the exorbitant rates charged for phone calls in jails and prisons, and the proposed rules similarly blame commissions for the high rates and fees charged by ICS (Inmate Calling Services) companies. The Commission found that “[e]ither ICS providers are operating at a loss, or are generating revenue by means other than inmate calls, or are shielding some portion of ICS revenue from commissions.” Furthermore, the commission found that “unnecessary or excessive ICS provider fees decreases the amount [of funds] devoted for inmate calls and reduces commissionable revenue.” To put it simply, high fees hurt incarcerated people as well as jails.

Continue reading →

Leah reports back from a hearing on the zone law before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

by Leah Sakala,

October 8, 2013

The Massachusetts Legislature took a step in the right direction last year when it reformed the state’s sentencing enhancement zone law. But now the highest court in Massachusetts must decide just when the new law began to take effect.

Basically, lots of states have sentencing enhancement zone laws that aim to keep illegal drug activity away from kids by saying that if you commit drug offenses within a certain distance of a place like a school, you get a mandatory extra sentence for your crime. But until last August, the Massachusetts law created enormous 1,000-foot zones that blanketed entire urban areas. Our two reports found that huge zones end up defeating the whole purpose of the law because when you make everywhere special, nowhere is special. Furthermore, the law increases racial disparities in the justice system because dense, urban communities that are disproportionately made up of people of color are most impacted by zone laws.

Last August, the Massachusetts legislature realized that the 1,000-foot zones weren’t doing the job, and were actually causing harm. So lawmakers took our advice to reduce the size of the zones, reining them in to a more reasonable 300 feet.

Yesterday I attended a hearing in Boston before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to consider which version of the law should apply to people who were arrested before last year’s law change, but sentenced afterwards. Since this case is largely revolves around a procedural question, much of the hearing was spent talking about the technicalities of the legislation.

For me, the most memorable moment was when the District Attorney raised a concern that applying the law retroactively could create a disparity between people who had their court dates before the law was changed, and everyone else. Without skipping a beat, Justice Gants responded by pointing out that the legislature changed the law precisely because the old policy created disparities by giving prosecutors incredible power to bring an extra sentencing charge against people who primarily come from urban communities of color.

At the end of the day, as FAMM’s Barbara Dougan argued in her Amicus Brief, it’s clear that last year’s reform to shrink the size of the zones was intended to immediately improve a major flaw in the 1,000-foot law. Sentencing people to extra prison time based on a law that the legislature has since rejected is clearly not a good policy.

We’ll be following the outcome of this case closely, so stay tuned for updates and a ruling. Also, keep your eyes peeled for our newest video on sentencing enhancement zones. We’re hoping to wrap it up this week!

"...locking up unprecedented numbers of citizens over the last forty years has itself made the prison system highly resistant to reform through the democratic process."

by Leah Sakala,

October 7, 2013

Chances are, your high school U.S. History class didn’t quite tell you the whole story about how the criminal justice system has cast its shadow on U.S. democracy for centuries. Here’s a chance to get the record straight.

Heather Ann Thompson, historian and Prison Policy Initiative board member, just published a must-read new article in The Atlantic, “How Prisons Have Changed America’s Electoral Politics.”

As Heather writes,

…locking up unprecedented numbers of citizens over the last forty years has itself made the prison system highly resistant to reform through the democratic process. To an extent that few Americans have yet appreciated, record rates of incarceration have, in fact, undermined our American democracy, both by impacting who gets to vote and how votes are counted.

Of course, one of the ways mass incarceration distorts democracy is via prison gerrymandering. Heather explains:

Today, just as it did more than a hundred years earlier, the way the Census calculates resident population also plays a subtle but significant role. As ex-Confederates knew well, prisoners would be counted as residents of a given county, even if they could not themselves vote: High numbers of prisoners could easily translate to greater political power for those who put them behind bars.

The full article is absolutely worth a read. We, the people, deserve to know the whole story.

Disturbing laws that allow state and federal governments to keep certain people convicted of sex offenses behind bars indefinitely.

by Peter Wagner,

October 2, 2013

Our friend and colleague James Ridgeway has released a must-read expose on disturbing laws that allow state and federal governments to keep certain people convicted of sex offenses behind bars indefinitely:

Through a legal procedure called “civil commitment”, you can be classed as a sexually violent predator based solely on the subjective opinion of a state-employed psychologist or sex expert.

Once placed under a civil commitment, you are essentially in prison indefinitely. This can quickly become a nightmare, particularly in instances such as an “agreed disposition” – similar to a plea bargain in a criminal trial – where a person may have been pushed to waive his right to appeal during negotiations.

The article concludes:

While there are, undoubtedly, some irremediable sex offenders who need to be confined for reasons of public safety, the civil commitment protocol denies some of the basic rights afforded other criminal defendants. These include the right to a speedy trial, full right to counsel and, perhaps most importantly, the right to introduce testimony from a defendant’s own experts. Without the protection of this last right, some defendants are sent off to prison for an indefinite sentence on the basis of questionable opinions from the state’s expert witnesses.

Civil commitment for sex offenders needs to be reformed root-and-branch or abandoned. The policy may be popular in law enforcement circles, fewer than half of US states have such laws. But in those states that have it […] most do not escape this largely invisible American gulag.