The Geography of Punishment:

How Huge Sentencing Enhancement Zones Harm Communities, Fail to Protect Children

by Aleks Kajstura, Peter Wagner, and William Goldberg

Prison Policy Initiative

July 2008

Section:

Deterrence, in Theory and Practice

The intent of sentencing enhancement zone laws is simple: to encourage drug dealers to stay away from children, thereby protecting children from drugs and drug-related behavior. Governor Michael Dukakis proposed the law in 1989, saying that “we want kids to be able to go to school without running the gauntlet of drug pushers.”[8]

Geography-based deterrence laws increase the penalty for offenses committed within specified zones, with the goal of encouraging people to move out of the zone before committing the offenses. Massachusetts courts have ruled that the sentencing enhancement applies regardless of whether a defendant knew he was inside a zone.[9] This interpretation may be constitutional, but it is neither wise nor effective: if an offender is expected to avoid the zones, he must have a reasonable idea of where they are. In order for the zone law to be an effective deterrent, zones cannot cover the majority of a populated area, so the offender may choose to leave the zone without inadvertently entering another. They also need to be identifiable, so that an offender can stay outside them in the first place. The Massachusetts law fails on both counts.

The zones are so large that they overlap, imposing an enhanced penalty on massive areas, sometimes entire cities. When a zone covers huge amounts of land, including many properties that are not schools, it does not encourage offenders to move away from schools. The problem of overlap is especially pronounced in urban areas, where schools and other relevant facilities are numerous and close together. The New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing, which found that three-quarters of Newark was in an enhancement zone, has termed this problem the “urban effect.”[10] The map of downtown Holyoke on the cover of this report demonstrates how zone overlap covers entire communities. There is no written record clarifying the legislature’s reasoning for setting the zones at this particular distance.

A distance of 1,000 feet is extremely difficult to estimate reliably, making it difficult to infer where the zones are, but it is also often impossible to determine whether a particular location — particularly an urban one — is near a school at all. The statute’s original bill mandated that the zones’ borders be marked with “drug-free zone” signs,[11] but the provision was dropped.[12] When zones cannot be determined using common sense, an offender who wants to move to a non-zone area will be unable to do so. A statute that creates such a situation is by no means an effective deterrent.

An offender unable to distinguish between zone and non-zone areas will not move away from a school because he cannot find a non-zone area to move to. As it is, property lines of schools are unmarked and often far from obvious, and because of buildings or natural formations, a school may be invisible to someone walking near it. An enhancement zone, then, can be used to punish someone who had no intention of selling drugs to children and was, for practical purposes, nowhere near them.

In preparation for this report, we decided to determine how far 1,000 feet actually is. As illustrated above, the statute’s requirement that the distance be measured in a straight line, regardless of obstruction, puts many distant areas under the law’s jurisdiction. We set out to discover whether, under ideal circumstances, people can be seen 1,000 feet from a school and found that at 1,000 feet, a person is an almost-invisible speck. It is therefore unreasonable to assume that someone anywhere within 1,000 feet of school property intends to sell drugs to children at the school. (See photos in the sidebar 1,000 feet is further than you think.)

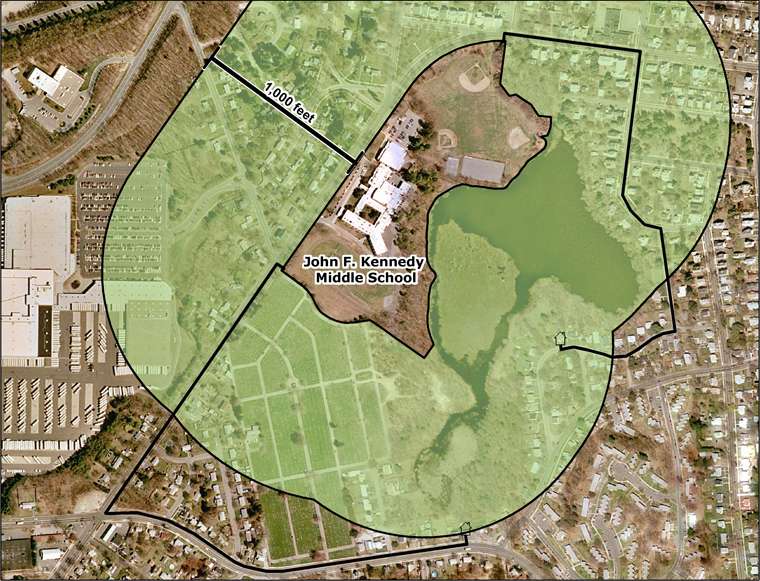

Figure 1. Because of a large pond, a cemetery and the roads’ arrangement, a person on Darling Street would need to travel 3,200 feet to get to the closest part of the JFK Middle School property, and a person on Page Boulevard would have to travel 3,800 feet to reach it. Yet the law requires that the sentencing enhancement zone distance be measured in a straight line from the edge of the property, regardless of the obstacles in between.

Figure 2. 1,000-foot zones are so large that the zone around Holyoke’s Dean Technical High School crosses the Connecticut River and reaches Chicopee. The driving distance from Bonner Street in Chicopee to the Technical High School in Holyoke is 4.4 miles and would take about 11 minutes.

Footnotes

[8] Peter J. Howe, School drug-free plan touted: Mass. local leaders asked to back bill, THE BOSTON GLOBE, Jan. 8 1989, at 34.

[9] E.g., Commonwealth v. Alvarez, 413 Mass 224, 229-230 (1992).

[10] REPORT ON NEW JERSEY'S DRUG FREE ZONE CRIMES & PROPOSAL FOR REFORM 14 (The New Jersey Commission to Review Criminal Sentencing) 2005, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20210309181522/http://sentencing.nj.gov/dfz_report_pdf.html

[11] Peter B. Sleeper, Bill would try to curb schoolyard drug sales; Dukakis wants tough penalties for offenders, THE BOSTON GLOBE, Jan. 7 1989, at 30.

[12] Some Massachusetts schools currently post “drug-free zone” signs on their buildings, but there is no note of where school property ends, or indication that the sign alludes to an increased penalty for drug offenses and is not simply a standard to which the school aspires. For example, teachers sometimes post “Hate-Free Zone” stickers to signify that remarks against GLBT people are unwelcome in their classrooms. Though the two use the same terminology, there is no way to determine which violation may result in detention and which may result in the punitive power of the state.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.