In prisons, Blacks and Latinos do the time while whites get the jobs

The Attica prison rebellion resulted from a racial/ethnic disparity between the incarcerated and the staff. Decades later, that disparity still hasn't changed.

by Rachel Gandy, July 10, 2015

A driving force behind what New York State called “the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War” was a shocking racial and ethnic disparity between the incarcerated and the staff at Attica Correctional Facility. But 44 years later, that disparity doesn’t look much different. Not only is this problem not unique to 1971–it’s not unique to Attica or to New York State. Stark racial and ethnic differences between incarcerated people and staff members continue to persist in Attica, New York State, and across the national prison landscape.

The Attica prison rebellion of 1971

On September 9, 1971, a four-day prison rebellion began at the Attica Correctional Facility in New York State. Upset with their difficult living conditions, a group of incarcerated men took control of the prison. Their demands included some common sense changes, like a healthier diet, less mail censorship, and better educational and rehabilitative opportunities. When negotiations failed, Governor Rockefeller ordered the state police to take the facility back while the media watched on. In the assault, 38 people — 29 incarcerated men and 9 hostages — were killed instantly.

In the following years, New York improved the food, mail policies, and rehabilitative programs, but one grievance proved more difficult to fix — the racial and ethnic disparities between the incarcerated and the staff at Attica.

Disparities at Attica

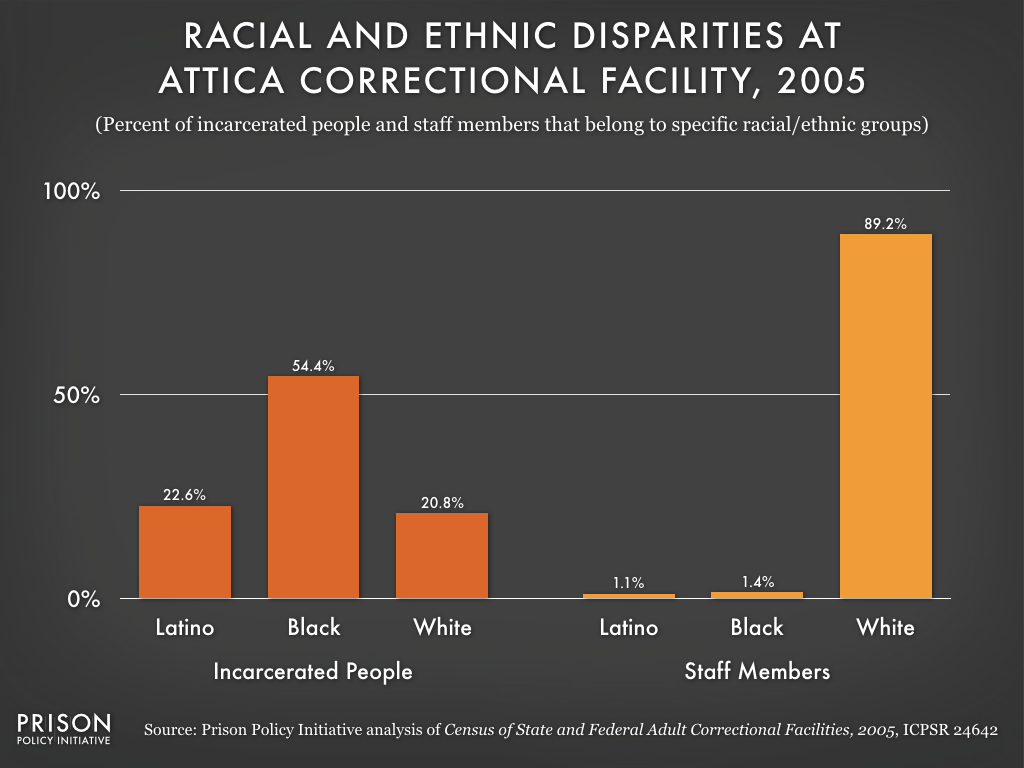

In 1971, 63% of the incarcerated population at Attica was either Black or Latino, but zero Blacks and only one Latino served as prison guards. The graph below shows that little changed in the years that followed:

Decades after the rebellion and massacre at Attica, the numbers of Latino and Black staff members were still very small relative to the numbers of incarcerated Latinos and Blacks. By 2005 (the latest year with complete comparable data), the number of Latinos working at Attica had increased to only 9 employees, or 1% of the facility’s workforce, despite Latinos making up almost 23% the incarcerated population. Similarly, Blacks held only 1.4% of Attica’s staff positions but represented over half (54%) of the incarcerated population.

Disparities in New York

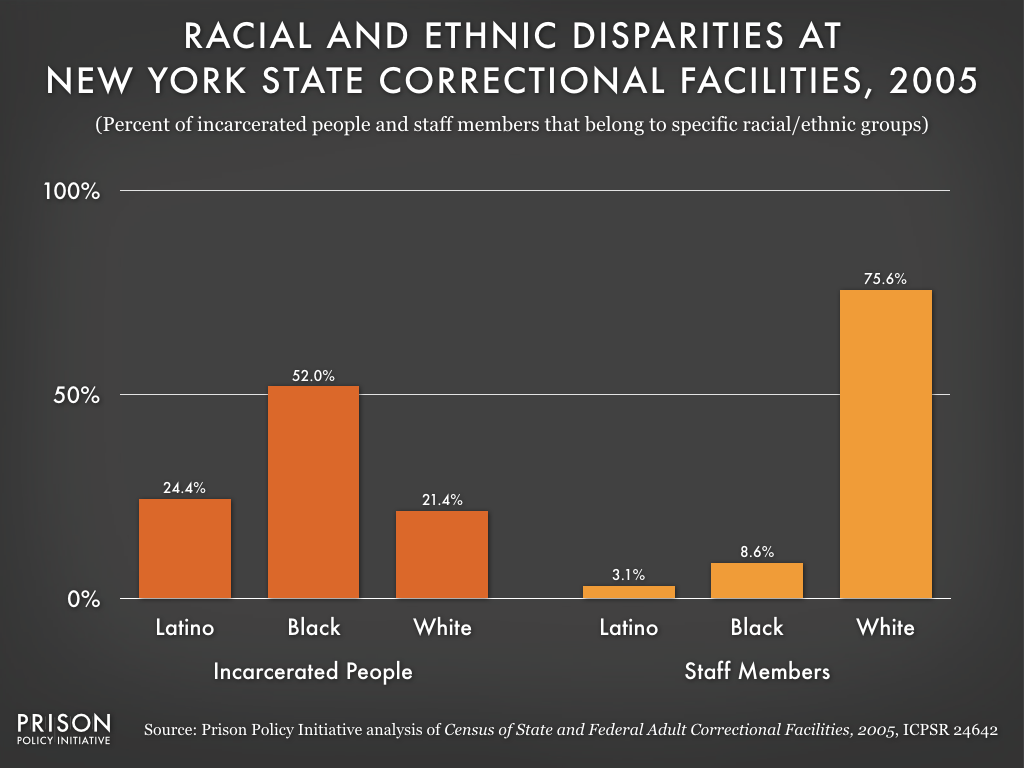

The pattern at Attica is echoed at facilities across New York State and illustrated in the graph below:

In 2005, Latinos held 3% of staff positions but represented about 24% of New York State’s incarcerated population. The difference was even more pronounced for Blacks, who held less than 9% of staff positions but represented almost 52% of the incarcerated population. Together, Latinos and Blacks held less than 12% of staff positions but made up over 76% of the incarcerated population.

Disparities across the U.S.

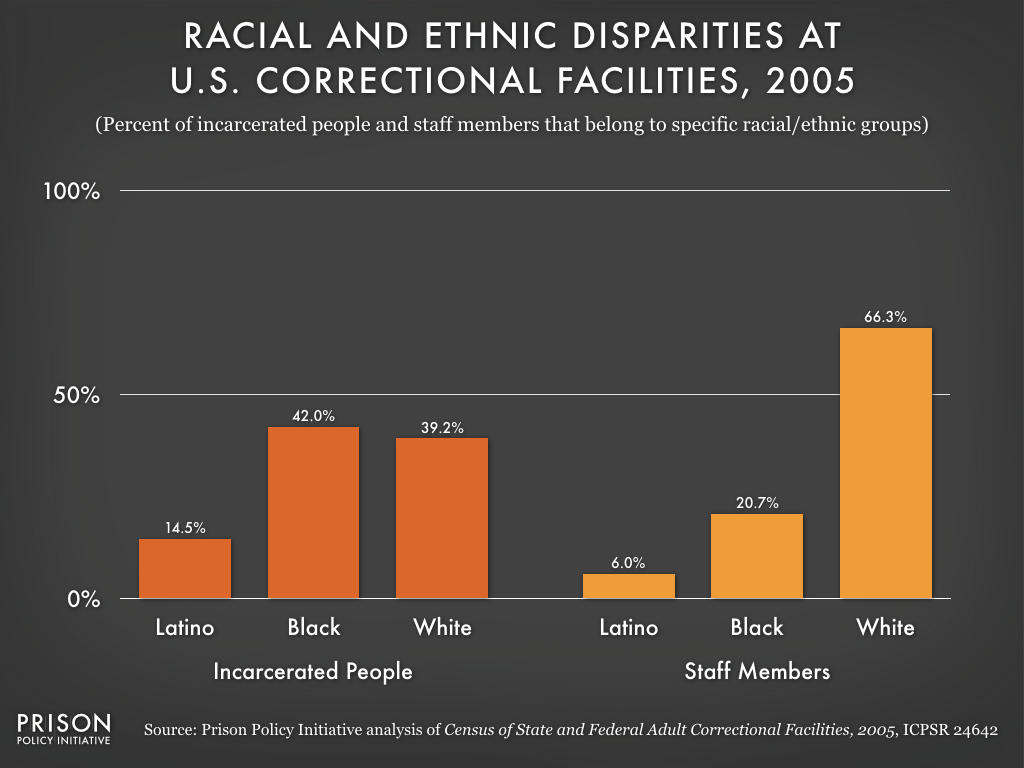

New York is not unique in having large racial and ethnic disparities between its incarcerated population and its prison staff members. The graph below shows that this is a national problem:

In 2005, Latinos and Blacks made up over half of the total incarcerated population, but they only held about a quarter of the correctional staff positions. Nationwide, incarcerated Blacks and Latinos are disproportionately overseen by white correctional employees.

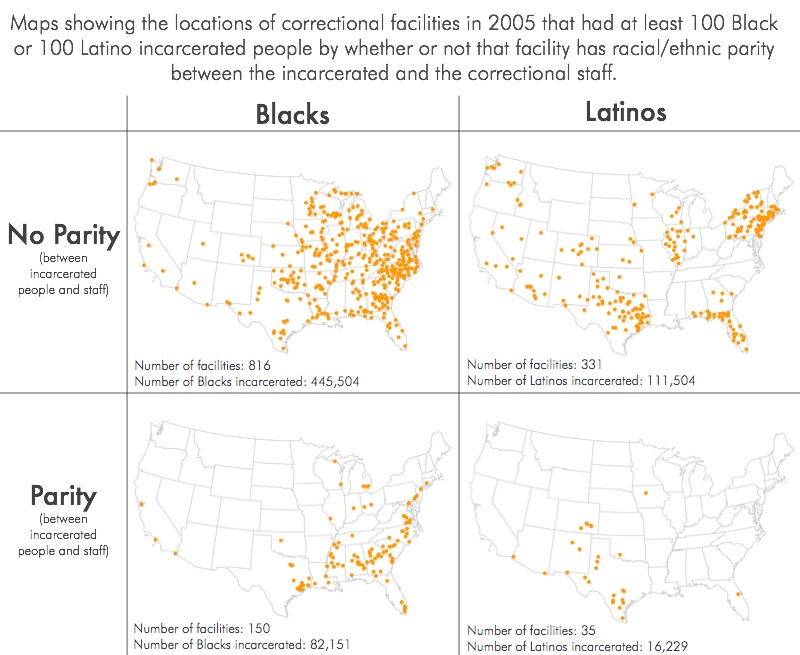

Attica is an extreme case in what is clearly a national problem. Some facilities, however, do have racial or ethnic parity between incarcerated people and correctional staff, and there is a distinct pattern in where such facilities are located. We mapped the facilities that do and do not have racial or ethnic parity (ignoring any facilities that had less than 100 incarcerated Blacks or Latinos):

The maps show that most correctional facilities with more than 100 incarcerated Blacks or Latinos are located in places where hiring Black and Latino staff in proportional numbers to the incarcerated population is extremely difficult. The small number of facilities that have such parity are, unsurprisingly, located in parts of the country with large populations of Black or Latino residents.

The maps show that most correctional facilities with more than 100 incarcerated Blacks or Latinos are located in places where hiring Black and Latino staff in proportional numbers to the incarcerated population is extremely difficult. The small number of facilities that have such parity are, unsurprisingly, located in parts of the country with large populations of Black or Latino residents.

(Not shown are 670 facilities that incarcerated less than 100 Blacks and 1,089 facilities that incarcerated less than 100 Latinos. Also excluded from our analysis were 141 facilities that did not report how many Blacks were incarcerated and 324 facilities that did not report how many Latinos were incarcerated.)

Why hasn’t this problem been fixed already?

The lack of progress at Attica since the 1971 rebellion isn’t hard to understand. Incarcerated men there wanted the racial and ethnic makeup of prison staff to change, but the location of the prison could not. Attica remained in a rural, overwhelmingly white part of New York State, while the Latinos and Blacks whom administrators needed to recruit lived in other parts of the state.

Researchers and government officials have known about this problem for more than 40 years. In 1971, the Department of Justice formed a Task Force on Corrections to outline the government’s national criminal justice standards and goals for the first time. After two years of researching and visiting correctional facilities, task force members found that:

“Location has a strong influence on an institution’s total operation. Most locations are chosen for reasons bearing no relationship to rationality or planning. Results of poor site selection include inaccessibility, staffing difficulty, and lack of community orientation.”

In its report, the task force went on to explicitly describe the disadvantages of building new prisons in rural areas. The authors found that rural facilities lead to

“…the consignment of corrections to the status of a divided house dominated by rural white guards and administrators unable to understand or communicate with black, Chicano, Puerto Rican, and other urban minority inmates.”

One member of the task force, leading scholar William Nagel, wrote his own book about the discoveries he made while working on the Department of Justice report. He noted that, by the late 1960s, government leaders were aware that isolating incarcerated people from the rest of society failed to prepare them for life after prison. For example, in 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson tasked the Commission on Law Enforcement and the Administration of Justice with developing practices that would better reintegrate incarcerated people into their communities.

Nagel therefore expected that he would find evidence that the government was already addressing these problems by building new prisons in populous cities, not isolated rural towns. But he quickly realized that this was not the case. Nagel and his research team found that all new correctional facilities, except for jails in county seats and small special purpose facilities, were being built in rural areas.

a prison was opened in a rural town every 15 days throughout the 1990sAnd, sadly, things were about to get much worse. After Nagel and his task force published their findings, the prison boom — which was largely a rural prison boom — began in earnest. As researcher Tracy Huling and U.S. Department of Agriculture demographer Calvin Beale noted, a prison opened in a rural town every 15 days throughout the 1990s.

Decades after the Attica rebellion, this country is beginning to grapple with the questions of how, what kind — and how many — prisons it should have. Underlying this discussion should be one basic fact: location matters.

Methodology note:

By “white” this article relies on the Bureau of Justice Statistics numbers for “White, not of Hispanic origin”, and for Blacks, the figure for “Black or African-American, not of Hispanic origin”.

Footnotes

1. United States Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Census of State and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities, 2005. ICPSR24642-v2.

2. For this article, we define “employees” as full-time and part-time correctional employees.

3. U.S. Department of Justice, Task Force on Corrections of the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, Report on Corrections (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1973), 354.

4. Ibid.

5. William Nagel, The New Red Barn: A Critical Look at the Modern American Prison (New York: The American Foundation, Inc., 1973), 46.

6. Tracy Huling, “Building a Prison Economy in Rural America,” in Invisible Punishment: The Collateral Consequences of Mass Imprisonment, ed. Marc Mauer and Meda Chesney-Lind (New York: The New Press, 2002).

[…] Why do some states struggle to hire sufficient Black and Latino correctional staff? […]

[…] areas. This combination has tremendous implications for the prison system’s ability to hire appropriate numbers of Black staff, and it gives the problem of prison gerrymandering a distinct veneer of racial […]