Girls are being put behind bars more and more. Will Congress do anything to help?

by Joshua Aiken, September 30, 2016

While comprehensive criminal justice reform for adults has failed to pass in Congress, a bill lingering in the Senate could still overhaul how our juvenile justice system works. The bipartisan legislation, which passed the House by an overwhelming 382-29 vote, would create several new policies that juvenile justice advocates have been requesting for years.

The proposed reauthorization of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act would withhold funding from states that put youth in adult prisons, require states to collect data on racial disparities in the juvenile justice system, ban the practice of shackling pregnant girls, and prohibit states from locking up youth for “status offenses.”

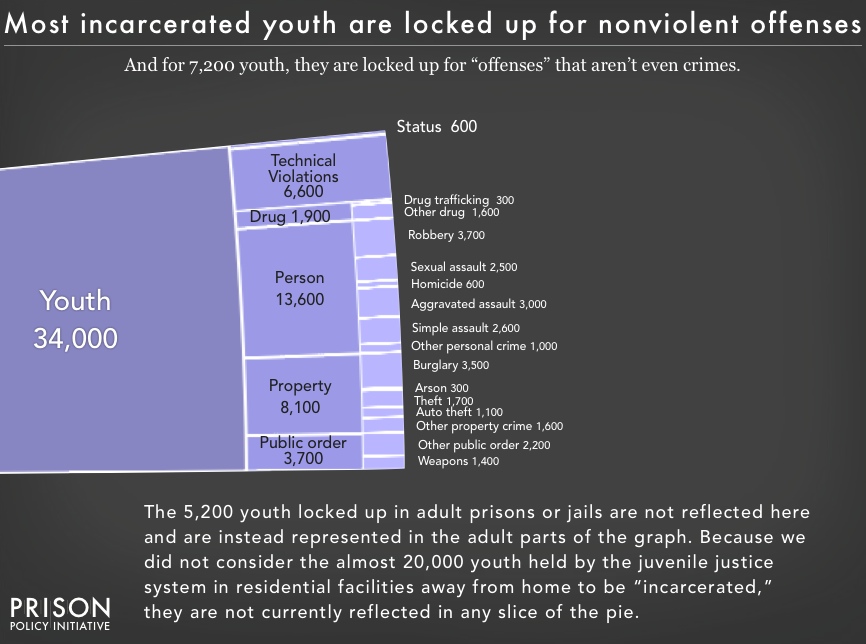

These reforms are desperately needed. In our 2016 report, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie we highlighted one of the most disturbing facets of our juvenile justice system: that we lock young people up for behaviors that are not law violations for adults—like running away or skipping school.

Talking about “status offenses” is important because status offenses aren’t even crimes. These offenses relate to a person’s age: skipping school, breaking curfew, or even talking back can land a young person behind bars. Increasingly, those young people are girls.

In an incredible piece for Mother Jones last week, Hannah Levintova details how bias and over-criminalization are ensnaring more and more girls into the criminal justice system. Levintova explains:

Between 1995 and 2009, cases of breaking curfew rose by 23 percent for girls—and just 1 percent for boys. In 2011, girls made up 53 percent of runaway cases brought before a judge. Between 1996 and 2005, arrests for “simple assault”—which could be as minor as a daughter throwing a toy at her mom—went up 24 percent for girls and down 4 percent for boys. By 2013, girls were almost twice as likely as boys to be in detention for simple assault and certain other nonviolent offenses.

Girls, argues Professor Andrew Spivak, are faced with types of “judicial paternalism” where “courts think that they need to protect girls and give them guidance.” Professor Stacy Mallicoat, in a 2007 study, showed that probation officers often attribute girls’ offending behaviors to their sexual behavior, drug use, and negative family relationships. Girls, and especially girls of color, get blamed. Meanwhile, when describing boys, probation officers were less likely to see their criminal behaviors as coming from these sources. As Levintova puts it, the justice system sees boy’s behaviors as “lifestyle choices” while the morals of girls are punished.

The disparate prosecution of status offenses sheds light on the deeply gendered ways our criminal justice works. And these offenses end up having a disastrous and long-lasting impact on girls:

Even a brief period in detention can lead to mental and

physical health issues, higher unemployment rates, lower lifetime

earnings, and substance abuse. The moral judgment that underlies the charges girls face can also change how they see themselves. “Once they internalize that they are ‘bad girls,'” says [Jeannette] Pai-Espinosa, “it almost creates a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The bill’s sponsors in the House are hopeful that the legislation can reach President Obama’s desk, but some legislators are strongly opposed.