New data: The rise of the “prosecutor politician”

Jed Shugerman argues that the prosecutor's office has become a "stepping stone to higher office... with dramatic consequences in American criminal law and mass incarceration." His extensive database explores connections between prosecutors and politics in each state since the 1880s.

by Wendy Sawyer and Alex Clark, July 13, 2017

Jeff Sessions has famously parlayed his reputation as a zealous and harshly punitive prosecutor into a powerful political career; but among the elite, is his background really so unusual? And to what extent do political ambitions influence prosecutors’ decisions?

It’s now possible to examine the scale of prosecutors’ influence on American politics and justice, thanks to Fordham University historian Jed Shugerman. On Friday, Shugerman announced a new project exploring the emergence and impact of “prosecutor politicians” in recent U.S. history. He also made his extensive database publicly available, which will be invaluable for those of us looking at the role of prosecutors in shaping our criminal justice system.

As part of his research into politicians who began their careers as prosecutors, Shugerman and a team of research assistants looked into the prosecutorial backgrounds of Supreme Court justices, circuit judges, state attorneys general, governors, and senators from each state since the 1880s. The result is a groundbreaking database of American public officials and their legal and political background, impressive in its historical and geographical scope and detail. (Shugerman is quick to point out that the database is a work in progress, one that he hopes will benefit from crowdsourcing additional documentation and analysis.)

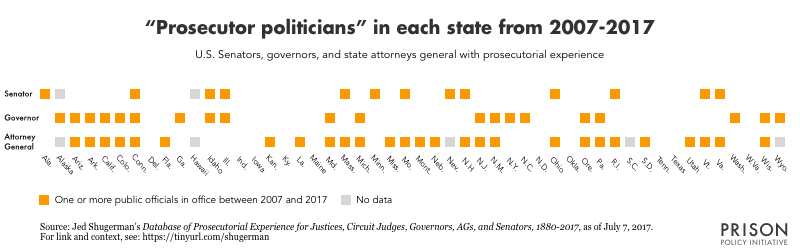

This research offers a new perspective – and critical new data – on the connections between prosecution and politics. In our initial look at the data, we focused on just public officials who have held office in the past ten years, and found examples of Shugerman’s “prosecutor politican” in 38 states. Of those in office at any point between 2007 and 2017, 38% of state attorneys general, 19% of governors, and 10% of U.S. senators had prosecutorial backgrounds.

In at least 38 states, a senator, governor, and/or attorney general holding office in the past 10 years was once a prosecutor. This chart may understate the prevalence of these “prosecutor politicians,” since the source is a work in progress and has no data for some positions in five states as of July 7, 2017, and does not include changes in all offices after January 2017.

In at least 38 states, a senator, governor, and/or attorney general holding office in the past 10 years was once a prosecutor. This chart may understate the prevalence of these “prosecutor politicians,” since the source is a work in progress and has no data for some positions in five states as of July 7, 2017, and does not include changes in all offices after January 2017.

According to Shugerman, the “prosecutor politician” has emerged as a political force in recent history, having a detrimental impact on our criminal justice system. Shugerman argues that the prosecutor’s office has become a “stepping stone for higher office… with dramatic consequences in American criminal law and mass incarceration.” This hypothesis dovetails with the work of John Pfaff, who argues that prosecutorial decisions explain much of mass incarceration.

Shugerman’s inspiration for the project was his observation that in recent history, prosecutors with political aspirations appear to have prioritized public opinion and personal gain over justice. Their decisions have, in turn, made justice outcomes more punitive for millions of civilians, and noticeably more lax for police. Shugerman hypothesizes that ambitious politicians are drawn to the prosecutor’s office, where they prosecute more arrests and develop a reputation for being “tough on crime.” Yet while they prosecute many defendants too aggressively, such prosecutors also fail to adequately prosecute police officers who have killed Black men: “Suburban/rural prosecutors generally underperform, and perhaps even sabotage, their prosecutions of police in these cases because of their own political ambitions.”

John Pfaff’s work turned the attention of criminal justice reformers to prosecutors earlier this year; and now Shugerman has offered us a tool to further gauge the scope of the problem. If Shugerman’s theory is correct, and prosecutors are subverting justice out of political ambition and fear of public reproach, changing justice outcomes will require greater scrutiny of prosecutors and their decisions.

The fact so many politicians were prosecutors shows why our justice system is in such dire straights. Prosecutors persecute. They don’t care about rehabilitation any more than cares about healing the wounded enemy. They’re grunts and look at the world from the grunt’s perspective.