In a series of graphics, we explain how tens of thousands of youth who could be better served in their communities still end up in confinement.

February 27, 2018

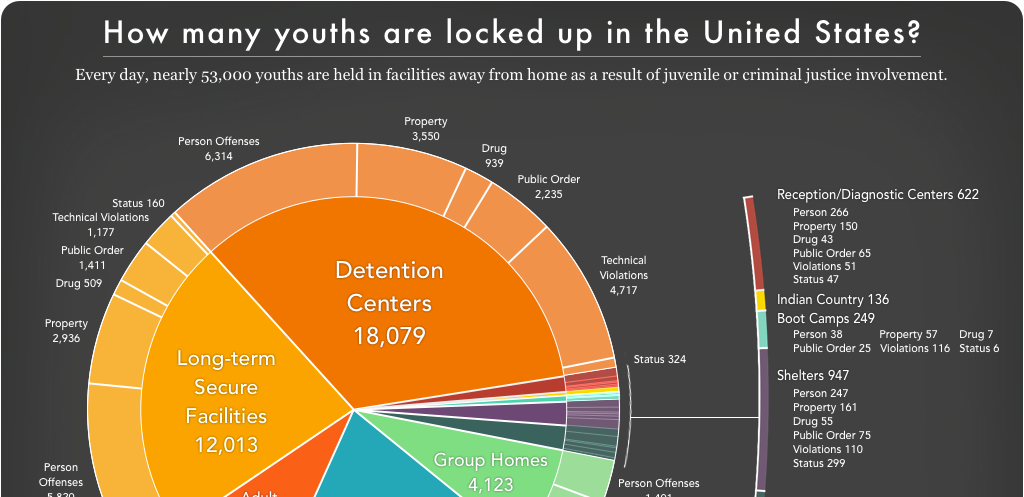

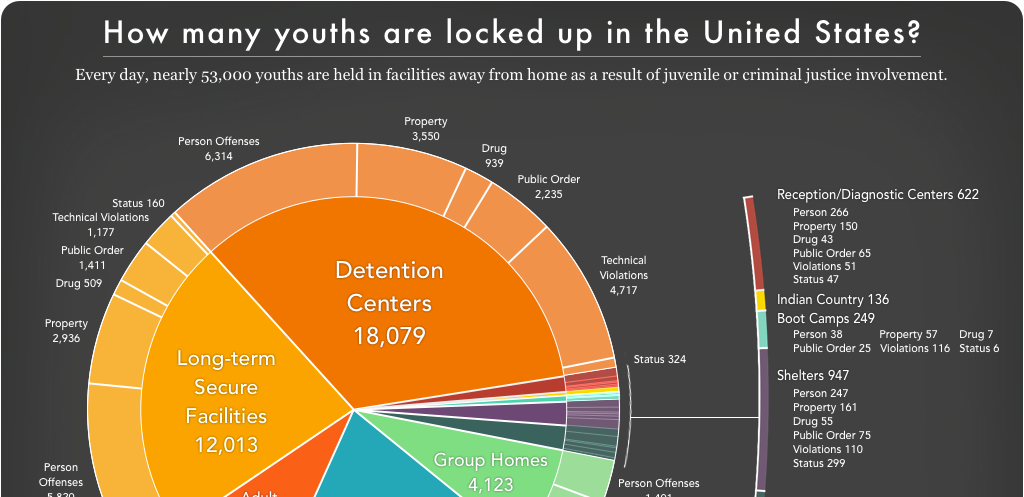

Easthampton, Mass. – A map of juvenile justice in America would be daunting, covering 1,852 youth facilities of varying restrictiveness, not to mention thousands of youth held in adult prisons and jails. Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie offers a comprehensive view of this system, breaking down where and why justice-involved youth are locked up.

In a series of graphics, the report reveals how tens of thousands of youths who could be better served in their communities still end up in confinement. Far from confining “only those youth who are serious, violent, or chronic offenders,” as the juvenile justice system purports to do, this country:

- Locks up 8,500 youths every day for technical probation violations

- Detains over 9,000 youths before they’re even tried – and holds 900 in long-term secure facilities, essentially prisons, before they’ve been committed

- Locks up over 7,500 youths for other low-level offenses, including status offenses (behaviors for which an adult would not be prosecuted)

Youths held pretrial or for minor offenses comprise 1 in 3 held in confinement today – children and adolescents who could be released at virtually no threat to public safety.

The report explores some of the worst harms of excessive youth confinement, including:

- Disproportionately punishing Black and Native youth, with disparities exceeding even those of the adult justice system

- Confining most youth in facilities indistinguishable from jails and prisons – or in actual adult jails and prisons

- Holding youth in “temporary” reception/diagnostic centers for months or even years

The big-picture view offered by Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie suggests opportunities for immediate reform, such as transferring youth to community-based programs and drastically curtailing pretrial detention. “For advocates working to find alternatives to incarceration,” says report author Wendy Sawyer, “ending youth confinement should be a top priority.”

Read the full report.

-30-

The number of youth locked up in adult facilities remains on the decline, but new jails data shows how much further we still need to go.

by Maddy Troilo,

February 27, 2018

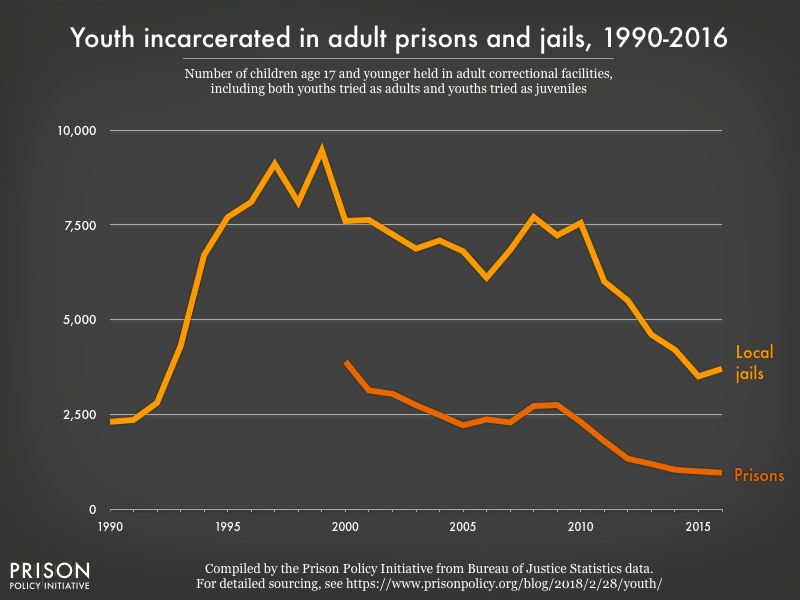

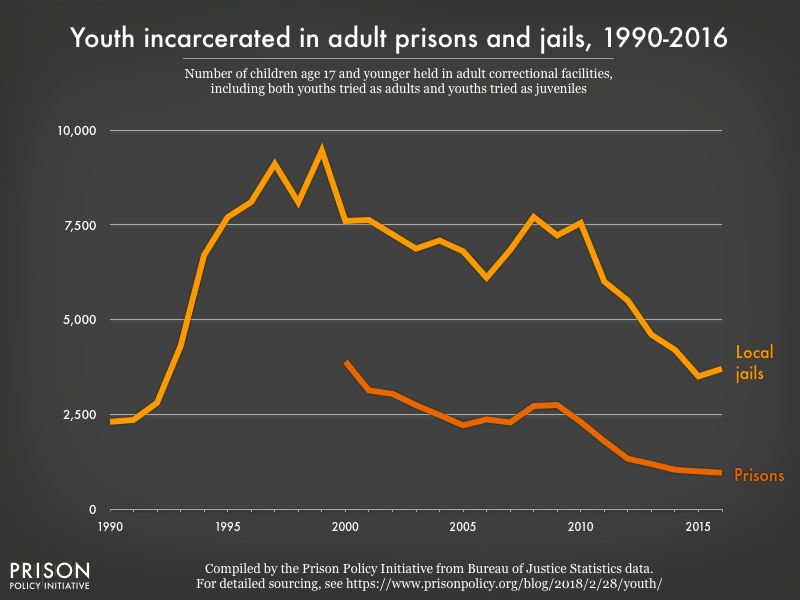

One of the overlooked findings of last week’s Jail Inmates in 2016 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics was that the number of youth locked up in adult jails grew over the year prior. The number of youth locked up with adults overall remains on the decline, but the new data shows how much further we still need to go:

Despite a significant decline in the number of youth incarcerated in jails since the peak in 1999, there are still more youths in jail than there were in 1990. And the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that the number of jailed youths actually went up in 2016.

Despite a significant decline in the number of youth incarcerated in jails since the peak in 1999, there are still more youths in jail than there were in 1990. And the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that the number of jailed youths actually went up in 2016.

As our new report Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie discusses, most detained youth are held in various youth-specific facilities, but one in ten are held in adult facilities. To support the new report, I’ve been collecting the data and exploring why youth end up in adult facilities and what happens to them once they do.

In some states, seventeen-year-old youths are automatically prosecuted as adults. In other states, certain offenses automatically require adult prosecution, and some states give prosecutors and the courts discretion to try youths as adults. Thirty-one states have “once an adult, always an adult” policies, which mandate that if someone under eighteen has ever been charged as an adult, all of their future cases must also be handled in the adult system.

Thirty years ago, there were 2,300 kids held in adult jails. From 1990 to 1999, youth jail populations increased by 311%, peaking at 9,458. That number then began to decline, culminating in a 2016 population of 3,700, still far more than the already-high 1990 number.

The data for prisons, available from 2000 forward, follows a pattern of consistent decrease. 3,892 kids were confined in adult prisons in 2000; by 2016 this number had fallen to 956 — still far too high.

The decline in number of youths in adult facilities represents a more general decline in the number of youths coming into contact with the criminal justice system. Between 2005 and 2014, the number of youths arrested dropped by 51.2%; similarly, between 1997 and 2013, the number confined in correctional facilities dropped by 48%. Some of the decline in youth incarceration, however, is the result of youths aging out of the statistics but remaining behind bars for crimes committed before they were eighteen.

Much of the general decline in youth confinement in adult facilities is the result of legal and legislative changes brought about by youth-focused criminal justice advocacy. In 2005, the Supreme Court ruled in Roper v. Simmons that imposing the death penalty for a crime committed while the offender was under eighteen violates the Constitution. In doing so, the court established the principle that children cannot be held to the same standards of responsibility as adults, nor can their actions be considered evidence of an “irretrievably depraved character.” This decision established the legal precedent for rollbacks of mandatory life sentences for juveniles and other policies that kept youth imprisoned.

States have also been taking independent legislative action, including raising the age of juvenile jurisdiction. Since juvenile courts are more likely to hand down sentences other than confinement, these laws reduce the number of people under eighteen who end up in jail or prison. State legislatures have also focused on delinquency prevention efforts, creating intervention programs for at risk-youth and diversion programs for nonviolent offenders.

While these legislative decisions are steps in the right direction, they still leave thousands of children in adult facilities, condemning them to countless long-term harms. The 2006 Justice Policy Institute report The Dangers of Detention summarizes the academic research on the harms of incarcerating youth in juvenile facilities, and shows that putting kids in cages:

- slows the natural process of aging out of delinquency,

- exacerbates any existing mental illnesses,

- increases the odds of recidivism,

- reduces the chances of returning to school, and

- diminishes success in the labor market.

Incarcerating youth in adult facilities is even more harmful than incarcerating them with people their own age. Of all incarcerated people, youth held with adults are at the highest risk of sexual abuse; they are also 36 times more likely to commit suicide than youth in juvenile facilities, and are at a greater risk of being held in solitary confinement than they would be in juvenile facilities.

These devastating and life-long effects come as the result of decisions made before age eighteen — an age when, according to research, youths’ brains are still years away from full development. This research further legitimizes the Supreme Court’s argument that children shouldn’t be held to the same standards of responsibility as adults. With that in mind, there’s absolutely no reason to punish them as adults.

Black and brown youth face a significantly higher chance of being held as adults than do white youth, an unjust disparity reflective of the racism that permeates the entire criminal justice system. According to the Campaign for Youth Justice, Black youth are 8.6 times more likely than their white peers to receive an adult prison sentence, while Latino youth are 40% more likely than white youth to be admitted to adult prison. These disparities reinforce those in the rest of the system by disproportionately subjecting youth of color to the harms of being incarcerated with adults.

Groups like the Campaign for Youth Justice and the Children’s Defense Fund are fighting against youth confinement in adult facilities by spearheading campaigns to raise the age of juvenile jurisdiction, advocating humane alternatives to confinement, and opposing policies that automatically place youths in the adult system. These are common sense reforms that should already be the law.

Data sources:

My Washington Post Op-ed explains how states continue to use the war on drugs to meddle with drivers' licenses.

by Aleks Kajstura,

February 12, 2018

In The Washington Post this weekend, I explained how states continue to use the war on drugs to meddle with driver’s licenses:

You’d expect to lose your driver’s license if you drove dangerously, but what if you ran afoul of the tax code, mail regulations or controlled-substance statutes? Sadly, in Virginia, that’s not a hypothetical question.

Virginia currently suspends nearly 39,000 driver’s licenses annually for drug offenses unrelated to driving. This is a relic of the war on drugs, and, while most states have opted out of the federal law that created these automatic suspensions, Virginia motors on.

As do 11 other states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Utah.

It’s time for these states to leave this practice in the dust. Or take the next legislative exit ramp. Or change lanes on reform. Or put the pedal to the metal… ok, you get the idea. More info available on our driver’s license campaign page.

Despite a significant decline in the number of youth incarcerated in jails since the peak in 1999, there are still more youths in jail than there were in 1990. And the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that the number of jailed youths actually went up in 2016.

Despite a significant decline in the number of youth incarcerated in jails since the peak in 1999, there are still more youths in jail than there were in 1990. And the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that the number of jailed youths actually went up in 2016.