Youth Confinement: The Whole Pie

By Wendy Sawyer

Press Release

February 27, 2018

This report is old. See our new version.

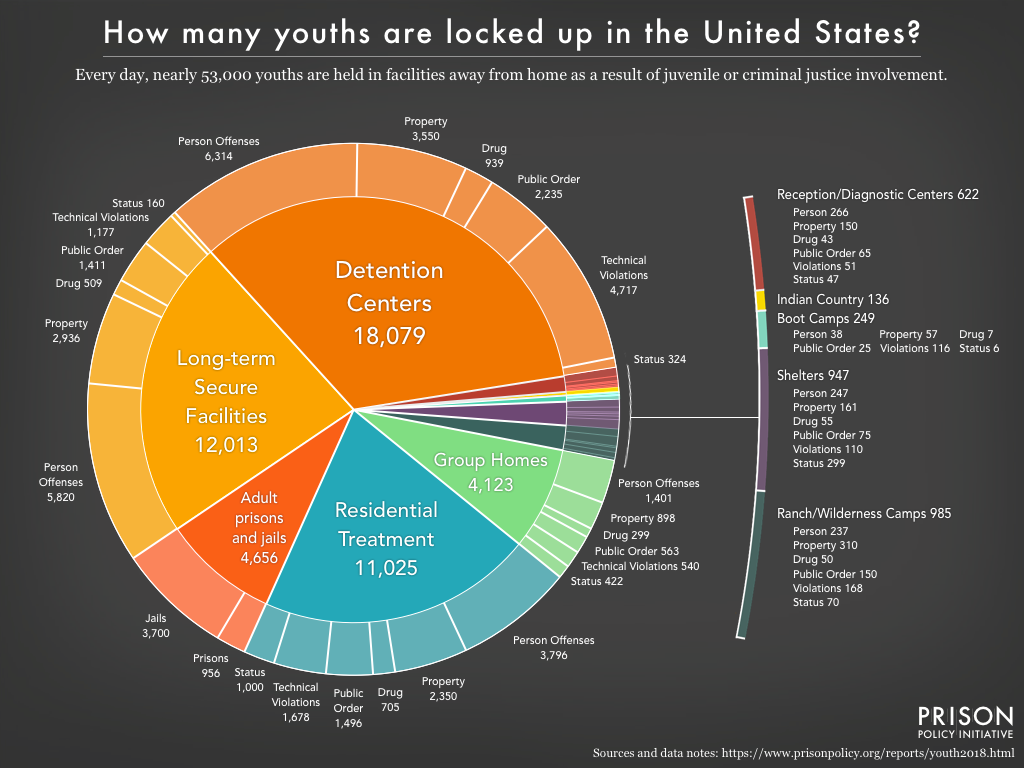

On any given day, nearly 53,000 youth are held in facilities away from home as a result of juvenile or criminal justice involvement. Nearly one in ten is held in an adult jail or prison. Even for the youth held in juvenile “residential placement,”1 the situation is grim; most of them are in similarly restrictive, correctional-style facilities. Thousands of youths are held before they’ve been found delinquent,2 many for non-violent, low-level offenses — even for behaviors that aren’t criminal violations.

This report provides an introductory snapshot of what happens when justice-involved youth are held by the state: where they are held, under what conditions, and for what offenses. It offers a starting point for people new to the issue to consider the ways that the problems of the criminal justice system are mirrored in the juvenile system: racial disparities, punitive conditions, pretrial detention, and overcriminalization. While acknowledging the philosophical, cultural, and procedural differences between the adult and juvenile justice systems,3 the report highlights these issues as areas ripe for reform for youth as well as adults.

Demographics and disparities among confined youth

Generally speaking, state juvenile justice systems handle cases involving defendants under the age of 18.4 (This is not a hard-and-fast rule, however; every state makes exceptions for younger people to be prosecuted as adults in some situations or for certain offenses.5) Of the 48,000 youths in juvenile facilities, more than two-thirds (69%) are 16 or older. Troublingly, more than 500 confined children are no more than 12 years old.6

Black and American Indian youth are overrepresented in juvenile facilities, while white youth are underrepresented. These racial disparities7 are particularly pronounced when it comes to Black boys and American Indian girls. While just 14% of all youth under 18 in the U.S. are Black, 43% of boys and 34% of girls in juvenile facilities are Black. And even excluding youth held in Indian country facilities, American Indians make up 3% of girls and 1.5% of boys in juvenile facilities, despite comprising less than 1% of all youth nationally.8

Most youth are held in correctional-style facilities

Justice-involved youth are held in a number of different types of facilities. (See “types of facilities” sidebar). Some facilities look a lot like prisons, some are prisons, and others offer youths more freedom and services. For many youths, “residential placement” in juvenile facilities is virtually indistinguishable from incarceration.

Most youth in juvenile facilities12 experience distinctly carceral conditions, in facilities that are:

- Locked: 89% of youth in juvenile facilities are in locked facilities. According to a 2014 report, 62% of long-term secure facilities and 43% of detention centers also use “mechanical restraints” like handcuffs, leg cuffs, restraining chairs, etc. Nearly half of long-term secure facilities and detention centers isolate youth in locked rooms for four hours or more.

- Large: 82% are held in facilities with more than 21 “residents.” Over half (52%) are in facilities with more than 51 residents. More than 10% are held in facilities that hold more than 200 youths.

- Long-term: Two-thirds (67%) of youth are held for longer than a month; about a quarter (23%) are held over 6 months; almost 4,000 youths (8%) are held for over a year.13

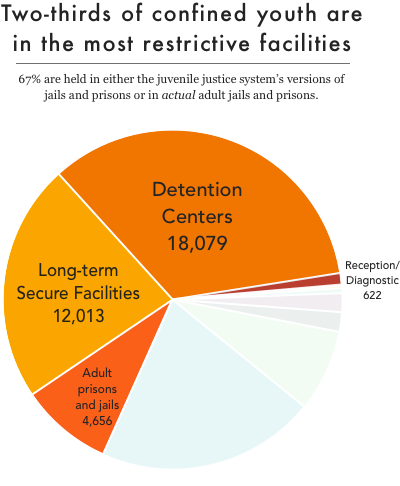

Two out of every three confined youths are held in the most restrictive facilities — in the juvenile justice system’s versions of jails and prisons, or in actual adult jails and prisons. 4,656 confined youths — nearly 1 in 10 — are incarcerated in adult jails and prisons,14 where they face greater safety risks and fewer age-appropriate services are available to them.15 At least another 30,714 are held in the three types of juvenile facilities that are best described as correctional facilities: (1) detention centers, (2) long-term secure facilities, and (3) reception/diagnostic centers.16 99.7% of all youth in these three types of correctional facilities are “restricted by locked doors, gates, or fences”17 rather than staff-secured, and 60% are in large facilities designed for more than 50 youths.

The largest share of confined youth are held in detention centers. These are the functional equivalents of jails in the adult criminal justice system. Like jails, they are typically operated by local authorities, and are used for the temporary restrictive custody of defendants awaiting a hearing or disposition (sentence). Over 60% of youth in detention centers fall into those two categories.18

But how many of the 18,000 children and adolescents in juvenile detention centers should really be there? According to government guidance, “…the purpose of juvenile detention is to confine only those youth who are serious, violent, or chronic offenders… pending legal action. Based on these criteria, [it] is not considered appropriate for status offenders and youth that commit technical violations of probation.” Yet over 5,000 youths are held in detention centers for these same low-level offenses. And nearly 2,000 more have been sentenced to serve time there for other offenses, even though detention centers offer fewer programs and services than long-term facilities. In fact, “National leaders in juvenile justice… support the prohibition of juvenile detention as a dispositional option.”

The most common placement for committed (sentenced) youth is in long-term secure facilities, where the conditions of confinement invite comparisons to prisons. Often called “training schools,” these are typically the largest and oldest facilities, sometimes holding hundreds of youths behind razor wire fences, where they may be subjected to pepper spray, mechanical restraints, and solitary confinement.19

Finally, reception/diagnostic centers - often located adjacent to long-term facilities - evaluate youth committed by the courts and assign them to correctional facilities. Like detention centers, these are meant to be transitional placements, yet over half of the youths they hold are there longer than 90 days. 1 in 8 youths in these “temporary” facilities is there for over a year.

Outside of these correctional-style facilities, another 17,000 youths are in more “residential” style facilities that are typically less restrictive, but vary tremendously, ranging from secure, military-style boot camps to group homes where youth may leave to attend school or go to work. Most of these youths (70%) are still in locked facilities rather than staff-secured, and conditions in some of these facilities are reportedly worse than prisons. About three-quarters of youth in these more “residential” facilities are in residential treatment facilities and group homes. Less frequently, youth are held in ranch or wilderness camps, shelters, or boot camps.

Locked up before they’re even tried

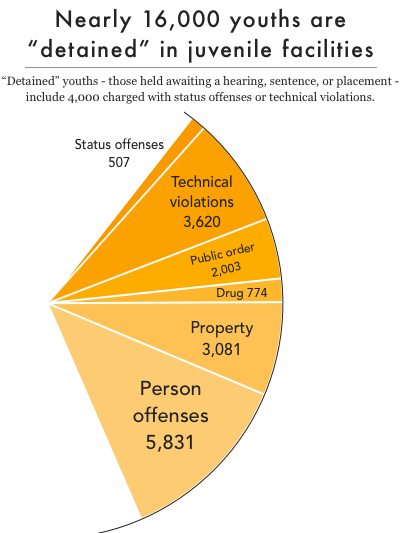

To be sure, many justice-involved youth are found guilty of serious offenses and could conceivably pose a risk in the community. But a disturbing number of youth held in juvenile facilities are not even serving a sentence.

More than 9,000 youths in juvenile facilities — or 1 in 5 — haven’t even been found guilty or delinquent, and are locked up awaiting trial (that is, a hearing). Another 6,500 are detained awaiting disposition (sentencing) or placement. Most detained youths are held in detention centers, but nearly 900 youths are locked in long-term secure facilities — essentially prisons — without even having been committed. Of those, only a third are accused of violent offenses.20

Even if pretrial detention might be justified in some serious cases, over 4,000 youths are detained for technical violations of probation conditions or for status offenses, which are “behaviors that are not law violations for adults.”21

Youth that are transferred to the adult system, meanwhile, can be subject to pretrial detention if their family or friends cannot afford bail. As a result, they may be jailed in adult facilities for weeks or months without even being convicted.

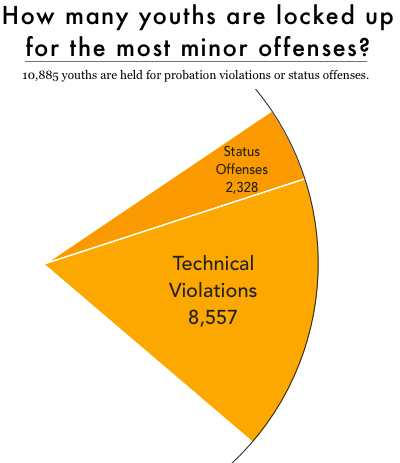

Incarcerated for minor offenses

Far from locking up youth only as a last resort, the juvenile justice system confines large numbers of children and adolescents for the lowest-level offenses. For almost a quarter of all youths in juvenile facilities, the most serious charge levelled against them is a technical violation (18%) or a status offense (5%).22 These are behaviors that would not warrant confinement except for their status as probationers or minors.

To see the number of youth held for these minor offenses in each type of juvenile facility, see this detailed view.

To see the number of youth held for these minor offenses in each type of juvenile facility, see this detailed view.

These are youths who are locked up for not reporting to their probation officers, for failing to complete community service or follow through with referrals — or for truancy, running away, violating curfew, or being otherwise “ungovernable.”23 Such minor offenses can result in long stays or placement in the most restrictive environments. Almost half of youths held for status offenses are there for over 90 days, and almost a quarter are held in the restrictive, correctional-style types of juvenile facilities.

Many youths could be released today without great risk to public safety

Incarceration has serious, harmful effects on a person’s mental and physical health, their economic and social prospects, their relationships, and on the people around them. This is true for adults, of course, but the experience of being removed from their homes and locked up is even more damaging for youth, who are in a critical stage of development and are more vulnerable to abuse. The broad harms of youth incarceration are well documented, from pretrial detention to conditions in juvenile correctional facilities (“youth prisons”) and adult facilities. There is growing consensus that youth confinement should be used only as a last resort, as evidenced by the declining number of incarcerated youth in recent years.

Yet tens of thousands of children and adolescents continue to be locked up each year for low-level offenses. By our most conservative estimation, almost 17,000 youths (1 in 3) charged with low-level offenses could be released today without great risk to public safety. These include over 2,000 youths held for status offenses, 2,000 held for drug offenses other than trafficking, over 3,500 held for public order offenses not involving weapons, and 8,500 held for technical violations.24

State and local officials should also look more closely at the detained population and consider how many of those youths would be better served in the community. Beyond those 17,000 youths in the low-level offense categories we have identified, over 6,00025 others are held before they’ve been found guilty or delinquent; many of these youths could also be considered for release.

Conclusion

Like the criminal justice and juvenile justice systems themselves, the efforts to reverse mass incarceration for adults and to deinstitutionalize justice-involved youth have remained curiously distinct. But the two systems have more problems — and potentially, more solutions — in common than one might think. Like so many adults who are unnecessarily detained in jails, thousands of justice-involved children and adolescents languish in detention centers without even being found delinquent. They, too, are locked up in large numbers for low-level, non-violent offenses. And many youth face similarly dehumanizing conditions when they are locked up in juvenile facilities that look and feel like adult jails and prisons. For advocates and policymakers working to find alternatives to incarceration, ending youth confinement should be a top priority.

Recommendations:

With this big picture view, it should be obvious that many improvements can be made to better respond to the behaviors and needs of justice-involved youth. Many juvenile justice-focused organizations have proposed policy changes at every stage of the process,26 but to address some of the issues discussed in this report, policymakers can start by:

- Updating laws to reflect our current understanding of brain development and criminal behavior over the life course,27 such as raising the age of juvenile court jurisdiction and ending the prosecution of youth as adults;

- Removing all youth from adult jails and prisons;

- Shifting youth away from confinement and investing in non-residential community-based programs;

- Limiting pretrial detention and youth confinement to the very few who, if released, would pose a clear risk to public safety;

- Eliminating detention or residential placement for technical violations of probation and diverting status offenses away from the juvenile justice system;

- Strengthening and reauthorizing the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act to promote alternatives to youth incarceration and support critical juvenile justice system improvements.

A note about language used in this report

Many terms related to the juvenile justice system are contentious. We have elected to refer to people younger than 18 as “youth(s)” and avoid the stigmatizing term “juvenile” except where it is a term of art (“juvenile justice”), a legal distinction (“tried as juveniles”), or the most widely used term (“juvenile facilities”). We also chose to use the terms “confinement” and “incarceration” to describe residential placement, because we concluded that these were appropriate terms for the conditions under which most youth are held (although we recognize that facilities vary in terms of restrictiveness). Finally, the racial and ethnic terms used to describe the demographic characteristics of confined youth (e.g. “American Indian”) reflect the language used in the data sources.

Finally, because this report is directed at people more familiar with the criminal justice system than the juvenile justice system, we occasionally made some language choices to make the transition to juvenile justice processes easier. For example, we use the familiar term “pretrial detention” to refer to the detention of youths awaiting adjudicatory hearings, which are not generally called trials.

Footnotes

- “Residential placement” refers to the out-of-home placement of a youth by the court in any juvenile facility. ↩

- The terminology of the juvenile justice system differs from that of the criminal justice system; for example, youth are found “delinquent” instead of “guilty.” See the “terminology” sidebar and for more information, see “Juvenile Court Terminology” by the National Juvenile Defender Center. ↩

- A full explanation of the juvenile justice process is beyond the scope of this report. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention offers a concise overview and diagram of the Juvenile Justice System Structure & Process. Prof. Michele Deitch authored a more comprehensive overview of the history, standards, legislation, and contemporary issues related to the juvenile justice system in Ch. 1 of the National Institute of Corrections’ “Desktop Guide to Quality Practice for Working with Youth in Confinement” (2014). ↩

- Each state decides what age limits and statutes fall under the jurisdiction of their juvenile justice system and who can be prosecuted within the criminal justice system. Currently, 5 states continue to automatically prosecute 17-year-olds as adults — Georgia, Michigan, Missouri, Texas, and Wisconsin. And in North Carolina, youths age 16 and older are automatically prosecuted in adult court; legislation was passed in 2017 to “raise the age” of juvenile court jurisdiction to 18, albeit for nonviolent offenses only, effective December 1, 2019. Several states have recently raised the upper limit of the juvenile system to protect more teenagers from incarceration in adult prisons and jails and from the consequences of adult convictions. Others are considering legislation to raise the age to over 18. Additionally, some states also define the lower bounds of the juvenile justice system; in North Carolina, for example, children as young as 6 can be adjudicated delinquent in the juvenile justice system. ↩

- In 2015, 25 states and the District of Columbia had at least one provision that allowed youth to be prosecuted as adults with no specified minimum age. In the states that specified a minimum age for transferring youth to criminal court, the youngest children that could be transferred were 10 years old (in Vermont and Wisconsin). ↩

- These young children are sometimes confined for long periods of time. At the time of the survey, about 10% of children 12 or younger had been held for more than 6 months; a handful had already been held for over a year. ↩

- The W. Haywood Burns Institute provides detailed data analysis of racial disparities in youth incarceration; for its analysis of trends in racial disparities, see the 2016 report “Stemming the Rising Tide: Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Youth Incarceration & Strategies for Change.” For another, more concise overview of the history and research on widening racial disparities among justice-involved youth, see Teen Vogue’s 2018 article, “The Criminal Justice System Discriminates Against Children of Color.” Data on the U.S. youth population by race and ethnicity for a given year can be found at The Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center. ↩

- Girls are also represented more in Indian country facilities than they are in all other juvenile facilities; girls make up 38% of all youth in Indian country facilities, compared to 15% of all youth in all other juvenile facilities. ↩

- According to 18 U.S.C. S 1151, “Indian country” refers to “(a) all land within the limits of any Indian reservation… (b) all dependent Indian communities within the borders of the United States… and (c) all Indian allotments, the Indian titles to which have not been extinguished….” ↩

- Some details are available in “Jails in Indian Country, 2016,” including a list of facilities by state, the number of youths 17 or younger held in each by gender, rated capacity of each facility, offense data, and conviction status. Unfortunately, youth in Indian country facilities cannot be compared to those in other juvenile facilities by age or offense type (these are reported differently than in the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement), and data on security type (locked versus staff-secured) and length of stay are not reported for Indian country facilities. ↩

- In 2016, all of the youth in adult prisons were incarcerated in state prisons. 49 youths age 17 or younger were under the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) jurisdiction; they were housed in facilities contracted by the BOP rather than in federal prisons themselves. ↩

- This does not include youth in Indian country facilities, as not all of these details are available in the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ report, “Jails in Indian Country, 2016.” ↩

- These time frames were measures of “days since admission” at the time of the survey, so they actually measure how long youth had already been held, not a disposition (sentence) length. These time frames are therefore not necessarily reflective of how long surveyed youths were ultimately confined. ↩

- According to federal legislation (the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, or JJDPA, and the Prison Rape Elimination Act, or PREA), youth should not be held in adult facilities unless being tried as adults or for limited logistical reasons, and when they are, they should be housed separately and protected from physical and “sight and sound” contact with adults. When youth and adults come into contact in these facilities, it should only be under direct staff supervision. Furthermore, facilities should avoid putting youth in isolation to comply with these standards. State compliance with JJDPA and with PREA’s “Youthful Inmates Standard” varies, however. ↩

- The Campaign for Youth Justice details many of the problems with incarcerating youth in adult facilities in its 2016 fact sheet, “Key Facts: Youth in the Justice System.” In 2016, The Atlantic reported, in greater depth, the risks of sexual abuse and violence to youth in adult facilities. Richard E. Redding’s report, “The Effects of Adjudicating And Sentencing Juveniles As Adults: Research and Policy Implications” in Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice (2003) discusses the impact of trying and sentencing youth as adults on deterrence, case outcomes, and recidivism, and the conditions of confinement differences between adult and juvenile facilities. ↩

- The 30,714 youths in detention centers, long-term secure facilities, and reception/diagnostic centers discussed in this section do not include those in similar facilities in Indian country. While most of the Indian country facilities holding youth age 17 or younger have “Juvenile Detention” or “Detention Center” in their names, “Jails in Indian Country, 2016” does not provide comparable facility details those in the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement. ↩

- The Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement states that “locks indicated” means “[the] facility indicated that juveniles are restricted within the facility or its grounds by locked doors, gates, or fences some or all of the time.” ↩

- Of the 18,079 youths in detention centers in 2015, 10,994 (61%) were detained before adjudication/conviction or disposition/sentencing. 7,242 were detained awaiting juvenile court adjudication (hearing), 1,052 were detained awaiting a criminal court hearing, 165 were detained awaiting a transfer hearing, and 2,535 were adjudicated but were detained awaiting disposition (sentencing). 3,972 (22%) were committed after adjudication or criminal conviction. The remaining 3,113 (17%) were detained awaiting placement, were placed there as part of a diversion arrangement, or for “other/unknown” reasons. ↩

- For more on “youth prisons,” see Youth First Initiative’s website; “The Facts,” Part III: “Through Their Eyes: A Snapshot of the Daily Lives of America’s Incarcerated Youth” has more detailed descriptions comparing youth prisons to adult prisons. For more on conditions of confinement in juvenile facilities, see “Survey of Youth in Residential Placement: Conditions of Confinement” by Andrea J. Sedlak, Ph.D. (May 2017). Note that the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement data is from 2003; the survey has only been conducted once so more recent data is not available. ↩

- Of the 885 youths detained in long-term facilities, 300 are held for person (violent) offenses. 228 are held for property offenses; and 357 are held for technical violations or drug, public order, or status offenses. ↩

- In “Juveniles in Residential Placement, 2013” (2016), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention defines status offenses as “behaviors that are not law violations for adults, such as running away, truancy, and incorrigibility.” For a deep dive into status offenses, see Vera Institute for Justice’s 2017 report “Just Kids: When Misbehaving Is a Crime .” ↩

- In 20 states, an even greater portion of confined youth in juvenile facilities are held for these offenses, including nearly half of those in West Virginia and New Mexico. ↩

- Although the JJDPA’s “Deinstitutionalization of Status Offenders” requirement states that youth charged with status offenses should not be placed in secure confinement, courts in some states take advantage of a loophole allowing judges to confine youth for status offenses if the offense violates a valid court order, such as “attend school regularly.” In FY 2014, this “valid court order exception” was used to confine 7,466 youths for status offenses in 26 states and the District of Columbia. Despite broad support to eliminate this exception, efforts to reauthorize the JJDPA have stalled because of one Senator’s insistence on keeping the option to lock up status offenders. ↩

- See the methodology for details about this estimate. For those curious about what behaviors are included in some of these offense categories, the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement Glossary states that “other drug offenses” include “drug possession or use, possession of drug paraphernalia, visiting a place where drugs are found, etc.” and “other public order offenses” include “obstructions of justice (escape from confinement, perjury, contempt of court, etc.), non-violent sex offenses, cruelty to animals, disorderly conduct, traffic offenses, etc.” 17,000 is a conservative estimate based on the most obvious low-level offenses, including status offenses, technical violations, and the offenses listed above. A more aggressive estimate could include all non-violent offenses. ↩

- Our estimate includes 6,379 youths detained in juvenile facilities and 56 unconvicted youths in Indian country facilities. It does not include any of the 3,700 youths detained in adult jails in 2016, even though many are likely unconvicted, because their conviction status was not reported. See the methodology for details. ↩

- A few excellent examples include recommendations from Act 4 Juvenile Justice, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Campaign for Youth Justice, W. Haywood Burns Institute, and the Youth First Initiative. ↩

- For a summary of this research, see “Community-Based Responses to Justice-Involved Young Adults” by Vincent Schiraldi, Bruce Western, and Kendra Bradner (2015). ↩

Read about the data

In an effort to capture the full scope of youth confinement, this report aggregates data on children and adolescents held in both juvenile and adult facilities. Unfortunately, the juvenile and adult justice system data are not completely compatible, both in terms of vocabulary and the measures made available.

Because we anticipate this report will serve as an introduction to juvenile justice issues for many already familiar with the adult criminal justice system, we have attempted to bridge the language gap between these two systems wherever possible, by providing criminal justice system “translations.” It should be noted, however, that the differences between juvenile and criminal justice system terms reflect real (if subtle) philosophical and procedural differences between the two parallel systems.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) provides easy access to detailed, descriptive data analysis of juvenile residential placements and the youths held in them. In contrast, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) provides very limited information on youth held in other settings. For youths in adult prisons, all that is readily accessible in government reports is their number by sex and by jurisdictional agency (state or federal). In annual government reports on jails, youths are only differentiated by whether they are held as adults or juveniles. Slightly more detailed information is reported on youths in Indian country facilities, but the measures reported are not wholly consistent with the juvenile justice survey, and facility-level analysis is necessary to separate youths from adults for most measures.

Despite these challenges, this report brings together the most recent data available on the number of youths held in various types of facilities and the most serious offense for which they are charged, adjudicated, or convicted. The only children and adolescents included in this analysis are involved in the juvenile- or criminal justice process. Youth who are put in out-of-home placements because their parents or guardian are unwilling or unable to care for them (i.e. dependency cases) are not included in this analysis.

For juvenile facilities, the most recent data available is from 2015, and for adult and Indian country facilities, 2016 data is available. These years matter: while most states set the upper age of juvenile court jurisdiction at 18, in 2015 and 2016, 7 states automatically prosecuted anyone 17 or older as an adult, and 2 states prosecuted anyone over 16 as an adult. For this reason, we expect that as more states continue to raise the age of juvenile court jurisdiction, the balance of youth in adult versus juvenile facilities will shift to greater reliance on juvenile facilities.

Data sources:

- Juvenile facilities: Most of the data in this report comes from the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (CJRP) in 2015. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) reports one-day counts of youths under 21 in “juvenile residential facilities for court-involved offenders” on the Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (EZACJRP) website. It includes facility data including facility self-classification (type), size, operation (local, state, or private), and whether it is locked or staff secure. It also includes data on the youth held in these facilities, including offense type, placement status, days since admission, sex, race, and age. The analysis of juvenile facility characteristics and demographics of youths in juvenile facilities are based on cross tabulation using the “National Crosstabs” tool.

- Adult jails: The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) reports the number of people age 17 or younger held in local jails with a breakdown of how many are held as adults versus juveniles in Appendix Table 1 of “Jail Inmates in 2016.”

- Adult prisons: BJS reports the yearend count of “prisoners age 17 or younger under jurisdiction of federal correctional authorities or the custody of state correctional authorities” in Table 11 of “Prisoners in 2016.” (The BJS Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) — Prisoners also reports these counts from 2000-2016.) Both “Prisoners in 2016” and “Prisoners in 2015” state that “The Federal Bureau of Prisons holds prisoners age 17 or younger in private contract facilities,” but it is unclear which facilities actually hold these youths. To avoid double-counting the 64 youths under Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) jurisdiction in 2015, for this report we assumed that these youths were captured in the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement data.

- Indian country: BJS reports the number of youths age 17 and younger in Indian country jails by facility and sex in Appendix table 4 of “Jails in Indian Country, 2016.” Although BJS provides a national estimate using data imputed for nonresponse in the same table (estimating 110 males and 60 females), we used the reported numbers (84 males and 52 females) because they correspond to the more detailed facility-level data. Using the breakdown by facility, we were able to determine how many youths are held in facilities that only hold youths versus those in combined adult/juvenile facilities. These youths are included in our total population of youth confinement, but excluded from analysis of the characteristics of juvenile facilities and youth in residential placement, which is based on the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement (CJRP) data. BJS reports some details that are similar to CJRP data, but do not match them enough to the two combine datasets (for example, offense categories are different, completely excluding technical violations and status offenses).

To compare racial and ethnic representation in juvenile facilities to the general population of all youths (17 or younger) in the U.S., we used general population data from the 2015 “Child population by race and age group” table by the Kids Count Data Center (The Annie E. Casey Foundation). We used the raw data to aggregate all children under 18 for comparison to the confined population in the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement.

The estimate of the number of youths confined for low-level offenses who could be considered for release includes 16,731 in juvenile facilities in 2015. 2,328 of these youths were held for status offenses, 2,186 for “other drug offenses,” 3,660 for “other public order offenses,” and 8,557 for technical violations. Additionally (although the offense categories are inconsistent with those in the CJRP), Indian country facilities holding only youths age 17 or younger held 60 youths for seemingly low-level offenses: 16 for public intoxication, 2 for DWI/DUI, and 42 for “other unspecified” (this dataset does not include technical violations or status offenses as offense categories). These youths could likely also be considered for release. We did not include youths held in adult prisons and jails in this estimate because offense types were not reported for these youths.

The estimate of the number of youths detained pretrial who could be considered for release includes 6,379 youths detained in juvenile facilities and 56 unconvicted youths in Indian country facilities.

At the time of the survey, 6,379 youths in juvenile facilities were detained awaiting either adjudication, criminal court hearing, or transfer hearing (essentially, they were being held before being found delinquent or guilty). This figure does not include the 2,923 youths detained for technical violations, status offenses, “other drug offenses,” or “other public order offenses” while they awaited these hearings, because we already included them in the roughly 17,000 youths held for low-level offenses that could be released.

“Jails in Indian Country, 2016” reports at least 56 unconvicted youths in facilities holding only people age 17 or younger. This may slightly underreport the unconvicted population, because the status conviction of youths in combined adult and juvenile Indian country facilities was not reported separately from the adults, and one juvenile facility did not report conviction status.

Youths held in adult prisons and jails were not included in this estimate because conviction status was not reported for these youths. However “Jail Inmates in 2016” notes that jails “may hold juveniles before or after they are adjudicated.”

Acknowledgements

This report was made possible by the generous contributions of individuals across the country who support justice reform. Individual donors give our organization the resources and flexibility to quickly turn our insights into new movement resources.

The author would like to thank her Prison Policy Initiative colleagues for their feedback and assistance in the drafting of this report, and intern Maddy Troilo for her supporting research on changes in youth incarceration in adult facilities over time. Elydah Joyce designed the main graphic, while Bob Machuga created the cover. We also acknowledge all of the donors, researchers, programmers and designers who helped the Prison Policy Initiative develop the Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie series of reports.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is most well-known for its big-picture publication Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie that helps the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform. This report builds upon that work and the 2017 analysis of women’s incarceration, Women’s Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie.

About the author

Wendy Sawyer is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. She is the author of Punishing Poverty: The high cost of probation fees in Massachusetts, and most recently, The Gender Divide: Tracking women’s state prison growth.

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.