We know how to prevent opioid overdose deaths for people leaving prison. So why are prisons doing nothing?

Treatment programs offer promising results for recently incarcerated people, but prisons aren’t using them.

by Maddy Troilo, December 7, 2018

The national opioid epidemic is killing formerly incarcerated people at shocking rates. Recent research from North Carolina, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island reveals the extent of this crisis and points towards possible solutions. Despite a growing body of evidence that specific treatments work effectively, most prisons are refusing to offer those treatments to incarcerated people, vastly worsening the overdose rate among people in and recently released from prison. Last month, the President signed into law the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, which aims to combat the national epidemic but will likely have mixed results. States, departments of corrections, and the federal government can and must do more to help.

The extent of the crisis

For as long as the data has been available, substance use disorders have affected incarcerated people at incredibly high rates. In 2009, the last time they collected national data, the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that almost two-thirds of incarcerated people suffer from substance use disorders and only a quarter of that group received any drug treatment while incarcerated. Further, as of 2005, less than 10% of formerly incarcerated people had access to substance abuse treatment after their release. The lack of treatment — as well as other documented challenges of reentry — contributes to the prevalence of drug overdose, the leading cause of death among recently incarcerated people. But how has the progression of the opioid epidemic influenced their experiences?

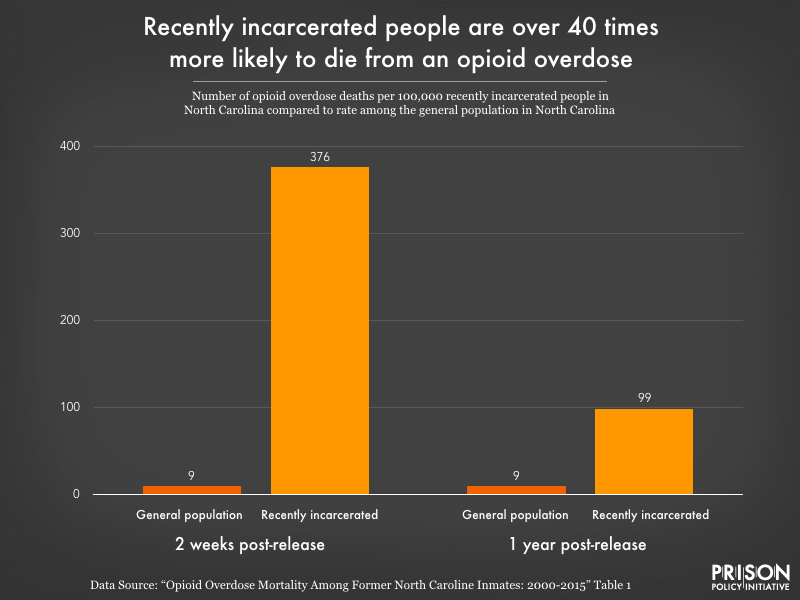

Only a few studies about opioid deaths among formerly incarcerated people have been conducted since 2010, when the nature of the epidemic changed with the shift to heroin use. One of these studies, Opioid Overdose Mortality Among Former North Carolina Inmates: 2000-2015, compares the rates of opioid overdose deaths among recently incarcerated people in North Carolina to those of the general North Carolina population. The results are staggering.

Recently incarcerated people in North Carolina are much more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public. The disparity is particularly extreme in the first two weeks after release, but they are still at 10 times greater risk even a year after release.

Recently incarcerated people in North Carolina are much more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public. The disparity is particularly extreme in the first two weeks after release, but they are still at 10 times greater risk even a year after release.

In the two weeks after their release, recently incarcerated people are almost 42 times more likely to die from an overdose than the general population. With such an apparent risk and dire consequences, states need to prioritize the widespread adoption of proven strategies to lower the risk of opioid overdoses among formerly incarcerated people.

In 2017, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health collected similar data as part of a broader study of the impact of the opioid epidemic in the state. The numbers are even more dramatic than North Carolina’s: they found that “the opioid overdose death rate is 120 times higher for those recently released from incarceration compared to the rest of the adult population.” Shockingly, in 2015, opioids accounted for almost 50% of all deaths among formerly incarcerated people. This is especially horrifying given that proven treatment methods for opioid use disorders exist — they just aren’t accessible to people in and recently released from prison.

What treatment options exist?

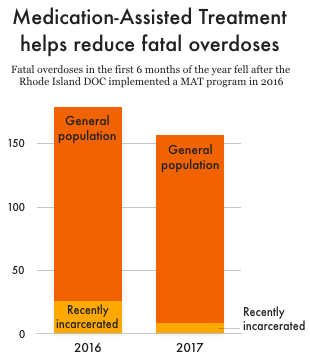

One exceptionally effective method for treating opioid use disorders is medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which much medical literature describes as the gold standard of care. MAT pairs counseling with low doses of opioids that, depending on the medication used, either reduce cravings or make it impossible to get high off of opiates. In the summer of 2016, the Rhode Island Department of Corrections launched a new program to provide MAT to some of the people incarcerated in their facilities. The early results are very encouraging: Rhode Island reported a 60.5% reduction in opioid-related mortality among recently incarcerated people in the first year after implementing the program.

A similar program in England had comparably encouraging results. A nationwide study of 39 prisons found that opioid-substitution treatment (another term for MAT) reduced overdose deaths by 85% in the first month after release. And the benefits of MAT programs go beyond reducing deaths: they improve the odds of staying in substance abuse treatment programs and reduce the chances of opioid use and recidivism during the first few months post-release. In the absence of these programs, many people are forced through a painful withdrawal that increases their chances of overdosing upon release. (This Boston Globe piece does an excellent job examining the personal impact of prisons refusing to provide MAT).

Beyond those promising prison-based treatments, states can benefit from wider implementation of MAT programs. For example, Rhode Island went beyond just implementing an in-prison MAT program, it also established 12 Centers of Excellence in MAT throughout the state, a strategic move that helped everyone in the state, including recently-released people. This program contributed to the 12.3% reduction in statewide overdose deaths Rhode Island experienced in 2017.

Complicating treatment options: the debate over the best medication

Clearly, medication-assisted treatment should be available in and out of prisons. But there are three different medications that can be used for MAT, and differing opinions as to which is best. Of these three medications, one stands out. Naltrexone, more commonly known by its brand name, Vivitrol, functions differently than methadone and buprenorphine (aka Suboxone). Methadone and buprenorphine — both opioids themselves — function as opioid agonists, meaning they latch onto opioid receptors in the brain and satisfy addicts’ cravings without getting them high. Vivitrol is an opioid antagonist, meaning it attaches to the brain’s opioid receptors and blocks opiates from reaching them, making it impossible to get high. It also requires that users completely detox for a full week before starting the medication. These differences, and the aggressive marketing and lobbying tactics of Vivitrol’s manufacturer, Alkermes, have sparked extensive debates in both the medical and political worlds.

Many of the debates about Vivitrol stem from the relative lack of evidence about its effects compared to those of methadone and buprenorphine. This was partially addressed in the fall of 2017, when the first study comparing the drugs head-to-head was released. The study revealed that Vivitrol works just as well as buprenorphine once it’s been started — but the initial detox requirement prevented over 25% of participants from even starting the medication. These results support the argument made by most doctors that no one medication works for everyone, so people should have access to all of them in order to find what works best for them.

Despite its flaws, Vivitrol remains by far the most popular opioid treatment medication in prisons (and is often the only one). The New York Times and ProPublica conducted an extensive investigation in 2017 into Alkermes’ lobbying and marketing tactics. These tactics include distributing Vivitrol to prisons for free as well as extensive — and successful — efforts to convince politicians (against the word of doctors!) that the other two medications are simply new drugs for people to become addicted to. In addition to spending almost $200,000 on donations to individual campaigns, Alkermes is a high-level corporate donor to ALEC, the notorious producer of conservative legislation; this has helped Alkermes get their product literally written by name into state laws.

Although some doctors accuse Alkermes of prioritizing its financial opportunities over actually fighting the opioid crisis, its product does have the capacity to help some users. Regardless, the evidence makes it clear: offering all three medications — not just one — helps the greatest number of people get clean and should thus be preferred by anyone who wants to reduce overdose deaths in and out of prisons.

Most state prison systems refuse to help

Despite evidence that medication-assisted treatment programs work and are worth expanding, almost every state in the country has refused to make meaningful investments in those life-saving programs. Vox’s 2018 investigation into the role of prisons in fueling the epidemic revealed that twenty-eight states offer nothing in the way of medication to incarcerated people with opioid use disorders. Out of the 46 states that provided data and do offer MAT, 16 offer only Vivitrol, one (Hawai’i) offers both buprenorphine and methadone, and Rhode Island is the only state that provides access to all three types of opioid addiction medications (methadone, buprenorphine/Suboxone, and naltrexone/Vivitrol).

The new federal law falls short

As important as it is that people receive medication-assisted treatment while in prison, it’s just as crucial that treatment continues after release. Ending treatment upon release puts people at a higher risk of turning back to non-medical opioids and therefore at a higher risk of overdosing: people’s tolerance for opioids goes down while they are receiving treatment, so doses that may have been non-fatal before treatment can kill them after stopping treatment. MAT isn’t free, though, which is one reason it’s incredibly important for people to have health insurance when they are released from prison. In 19 states, people on Medicaid lose their coverage when they are incarcerated and have to reapply for Medicaid when they are released (in 15 others, people lose their coverage after a specific period of time spent in prison). This tedious process often prevents or delays people from receiving coverage, and thus healthcare.

The recently-passed SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act partially addresses this issue. The act prohibits state termination of Medicaid eligibility for people under 21 who are held in public institutions, meaning that young incarcerated people will not have to re-apply for Medicaid upon their release in order to access coverage. This is a win that will make MAT and other important health care services more accessible to recently-incarcerated young people, but Congress needs to go further and expand this provision to people of all ages.

Unfortunately, other parts of the SUPPORT Act — ostensibly passed with the goal of tackling the opioid epidemic on a national scale — have the potential to seriously harm communities impacted by incarceration. The act authorizes millions of dollars in funding for police forces with high rates of drug seizures, further incentivizing police to arrest people on drug charges that could land them with unjustly long sentences. Responses to the opioid epidemic should focus on helping the people most affected by it, not funneling them into prisons that refuse to provide the treatment they need.

The criminal justice system does not have a good track record of dealing with public health issues. It needs to change that, and fast; failing to do so will allow the opioid epidemic to continue killing formerly incarcerated people. Medicaid expansions and access to medication-assisted treatment can help reduce the harm of opioids; states should focus on these and other treatment-based strategies, avoiding policies that will put more people behind bars. People with substance use disorders need accessible, affordable, and high quality healthcare — not time in prison.