LGBTQ youth are at greater risk of homelessness and incarceration

Homelessness is the greatest predictor of involvement with the juvenile justice system. And since LGBTQ youth compose 40% of the homeless youth population, they are at an increased risk of incarceration.

by Daiana Griffith, January 22, 2019

In a recent report, we found a strong link between incarceration and homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. But while we examined racial and age disparities among that population, we weren’t able to address how homelessness affects justice-involved youth — especially LGBTQ youth who are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. In this piece, we highlight research that elucidates the relationship between homelessness and LGBTQ youth incarceration, while also emphasizing how homelessness and incarceration disproportionately affect LGBTQ youth of color.

LGBTQ youth face higher rates of detention and incarceration. A 2015 study shows that 20% of all youth in the juvenile justice system identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning, gender nonconforming, or transgender, even though they compose only 5 to 7% of the total U.S. youth population. (Troublingly, the portion that identify as LGBTQ and/or gender nonconforming is even higher for girls in the juvenile justice system, at 40%.) This high percentage of justice-involved LGBTQ youth may be driven by their even higher rates of homelessness.

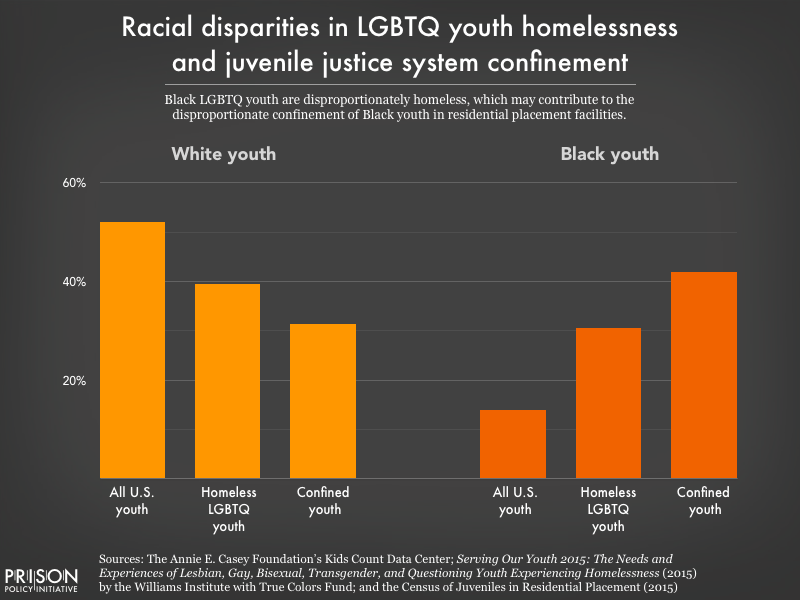

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

While white youth are underrepresented among the homeless LGBTQ youth and confined youth populations, Black youth are overrepresented among both groups. Black youth made up just 14 percent of the total youth population in 2014, but 31% of the homeless LGBTQ youth population that year, and 42% of the confined youth population in 2015.

According to a Center for American Progress report, homelessness is the greatest predictor of involvement with the juvenile justice system, and 40% of homeless youth identify as LGBT. LGBTQ youth usually face homelessness after fleeing abuse and lack of acceptance at home because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Once homeless and with few resources at hand, LGBTQ youth are pushed towards criminalized behaviors such as drug sales, theft, or survival sex, which increase their risk of arrest and detainment.

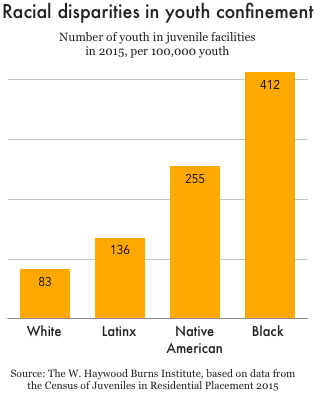

LGBTQ youth of color — particularly Black youth — are at an increased risk of criminalization. This, in part, reflects the fact that LGBTQ youth of color have disproportionately high rates of homelessness. A 2014 survey of human service providers serving homeless youth, for instance, reported that 31% of the LGBTQ youth they served identified as African-American or Black, despite Black youth making up only 14% of the general youth population in 2014. The racial disparities in youth homelessness contribute to the overrepresentation of youth of color in juvenile facilities in general; in 2015, 2 out of 3 youth in juvenile facilities were either Black, Hispanic, or American Indian.

The disparities in youth incarceration mean that LGBTQ youth, and especially youth of color, also face the harms related to incarceration at greater rates. Incarceration, for example, can be detrimental to young people’s physical and mental health, their relationships, and their social and economic prospects. Among these different consequences, access to stable housing can be especially negatively affected.

Youth in the juvenile justice system are likely to end up with juvenile delinquency records that can prevent them from accessing housing and finding employment once released. Similar to formerly incarcerated adults, justice-involved youth are subjected to discrimination by public housing authorities and private property owners, which, combined with affordable housing shortages, exposes them to housing insecurity.

In the case of justice-involved LGBTQ youth, housing discrimination based on criminal records can be compounded by housing discrimination against LGBTQ people. A 2017 study based in the D.C. metropolitan area found that housing providers were less likely to book an appointment with gay men, as well as less likely to tell homeseekers who disclosed their transgender identity about available units.

These alarming statistics remind us that LGBTQ youth are at a higher risk of both homelessness and incarceration, and the many harms accompanying these situations. This means that if we are to put less youth behind bars, we must address the specific needs of LGBTQ youth who often end up homeless because of family conflict. In addition, we have to make finding stable housing post-release and eradicating discrimination based on criminal records a priority to avoid cycles of reincarceration.

Daiana Griffith is a student at Mount Holyoke College, graduating in May 2019. She contributed this post as a student volunteer over the winter term.