Since You Asked: How did the 1994 crime bill affect prison college programs?

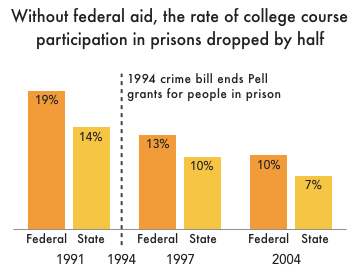

Without federal aid, the rate of college course participation in prisons dropped by half.

by Wendy Sawyer, August 22, 2019

Journalists, policymakers, and advocates frequently ask us to answer tricky but important questions about the criminal justice system. Until now, however, many of our answers to these common questions have gone unpublished, gathering dust in our email archives. This post is the first in what we anticipate will be an ongoing “Since You Asked” series that makes our answers to these important questions public. (Want to send us your questions? Use our contact page.)

Q: How many people participated in college-in-prison programs before and after the 1994 crime bill? (And how many participate in prison education programming today?)

A: To understand the drop in college participation in prisons following the 1994 “crime bill,” it’s important to know that most in-prison college programs, unlike colleges and universities in the “free world,” largely depend on funding from the Pell Grants program and other federal aid programs. This is largely because incarcerated people are overwhelmingly poor and can neither afford college tuition nor make generous gifts as alumni.

According to a historical overview by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), prisons “witnessed a surge in demand for college courses” after the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965, a law that greatly expanded federal aid for college participation nationwide. By 1982, 350 college-in-prison programs enrolled almost 27,000 prisoners (9 percent of the nation’s prison population), primarily through Pell Grants. … By the early 1990s, it is estimated that 772 programs were operating in 1,287 correctional facilities across the nation.”

A 1992 amendment to the Higher Education Act made people serving life sentences without parole and those sentenced to death ineligible to receive Pell Grants. Then, the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act banned everyone incarcerated in prisons from receiving Pell aid, even though these grants made up less than 1 percent of total Pell spending. “By 1997,” the AEI briefing continues, “it is estimated that only eight college-in-prison programs existed in the United States.” The remaining programs were those that received financial and volunteer support from other sources.

According to the American Historical Association, “States followed by further blocking access to funds through regional programs.” In 2005, the New York Times Magazine wrote that there were “about a dozen” prison college-degree programs, “four of them in New York State.”

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) 2003 publication Education and Correctional Populations includes some data that reflects these changes (see Table 4). In 1991, 13.9% of people in state prisons, and 18.9% of those in federal prisons, had taken a college course since admission. By 1997, these numbers had dropped to 9.9% for people in state prisons, and 12.9% in federal prisons. The 2004 BJS Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities (variable V2503) shows that the downward trend continued: In 2004, just 7.3% of respondents in state prisons had taken a college-level class since admission.

More recently, results from a 2014 study of people in prison found that 2% of respondents had completed an Associate’s degree while incarcerated, and 1% had completed a Bachelor’s degree or higher. Notably, 58% of respondents reported that they had not completed any further education while incarcerated.

But these statistics do not reflect a lack of interest in higher education among people in prison: To the contrary, 40% of respondents to the survey said that they would like to enroll in an Associate’s or Bachelor’s degree program, and an additional 29% wanted to enroll in a postsecondary certificate program. Nor are most people in prison unqualified for such programs: A recent report from the Vera Institute of Justice and Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality analyzed the same survey results and found that “the majority of incarcerated people are academically eligible for postsecondary-level courses.”

As we’ve previously found, educational exclusion is a strong predictor of incarceration in the U.S. But federal and state governments are far from powerless to repair the harm that results. Restoring Pell Grants to incarcerated people would make approximately 463,000 people in prison eligible for free college courses.

It’s time for the government to not only restore this critical aid, but expand it.