When parole doesn’t mean release: The senseless “program requirements” keeping people behind bars during a pandemic

Parole boards are granting parole contingent on participation in programs that are often not readily available for people behind bars, especially during the pandemic.

by Emily Widra and Wendy Sawyer, May 21, 2020

With public health officials and criminal justice reform advocates urging prisons to reduce their populations, people who have already been approved for release should be the first to return to their communities and families. Instead, thousands of them are waiting behind bars — where social distancing is impossible — as prisons across the country become the epicenters of the COVID-19 pandemic.

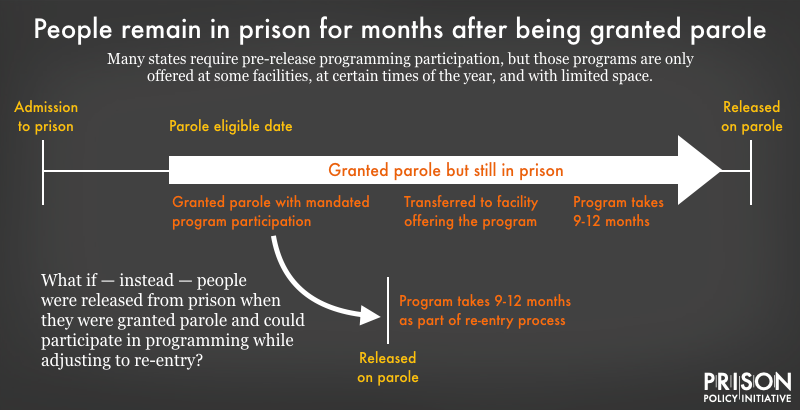

These are the people who have already been granted parole by the state parole boards, but have not yet taken a class or program that the parole board requires them to complete before they can go home. They are near enough to the end of their sentences to be parole-eligible, and the parole board has determined that they are “safe” to return to the community, but they cannot be released until they complete a program, often a drug and alcohol treatment program.

Tennessee offers a striking example of this potentially devastating policy failure. Over 1,300 COVID-19 cases in Tennessee are connected to a single state prison — Trousdale Turner Correctional Center — making it the third largest source of COVID-19 cases in the country. As Nashville defense attorney David Raybin explained to NewsChannel5, over 1,000 people in Tennessee prisons have been approved for parole but are waiting to participate in the mandated programming, most often the Department of Correction’s therapeutic community program, which lasts 9-12 months. That means Tennessee could reduce its prison population by almost 4% by releasing just those who have already been approved for parole.1

Evidence shows that these programs are effective whether offered before or after release, but states have been reluctant to offer these programs in communities instead of in prisons. But of course, education and treatment programming across the nation’s prison systems have been interrupted by the virus, as volunteers and educators are no longer entering the prison system on a regular basis; in Tennessee, the Department of Correction released a statement that the virus is causing “some disruption in programming.” Even in the best of times, participation in these programs is limited and people wait behind bars for a space in the program before they can be released.

This is not a new problem for Tennessee. Before the pandemic, a taskforce commissioned by the governor found that 40% of people granted parole from 2015-2019 had not actually been released because they were still waiting to participate in pre-release programs mandated by the parole board. That means that over those four years, more than 6,000 people were parole-eligible, reviewed and approved for release by the parole board, and then remained in prison simply because the mandated program was not offered at their facility or the maximum number of participants had already been reached.

Nor is this problem unique to Tennessee. A 2015 survey by the Robina Institute revealed that at least 40 states use “institutional program participation” as a factor in release decision-making for parole. In Texas, families have voiced their concern about loved ones who have been granted parole, but are still waiting to complete a pre-release program. Officials report that people often wait for months after being granted parole to begin these programs that provide education, life skills and employment training, substance abuse treatment, and other important re-entry supports. But waiting for programming that is on-hold or indefinitely postponed is no reason for people to remain in prison, especially when incarceration puts them at a heightened risk for contracting the virus.

If parole boards do not change this practice, for as long as the virus causes a “disruption in programming,” the number of people approved for parole but still in prison will continue to grow. The solution is obvious: Parole boards can waive the requirement or offer the therapeutic community programming after release. Especially given the current public health crisis, it makes sense for these programs — which, again, have been shown to be effective when offered after release — to be moved to the community setting when it is safe to do so. And in the meantime, people who have been approved for parole should be released as quickly as possible as part of the state’s efforts to protect incarcerated people and the larger community.

The Prison Policy Initiative is exploring doing a larger project evaluating prison programming, particularly the programming used to make parole decisions. If you happen to have copies of the curricula for any programs run in your state, please send a copy to virusresponse@prisonpolicy.org.

Footnotes

- Tennessee’s total prison population on March 31st, 2020 was 26,124, according to the Vera Institute of Justice’s recent report, People in Prison 2019, so releasing 1,000 people would be a 4% reduction. ↩