Research roundup: Violent crimes against Black and Latinx people receive less coverage and less justice

We explain the research showing that violent crimes against Black Americans - especially those in poverty - are less likely to be cleared by police and less likely to receive news coverage than similar crimes against white people.

by Katie Rose Quandt and Alexi Jones, March 18, 2021

Of 89 criminal cases recently solved with the growing but controversial use of genetic genealogy databases — all following the highly-publicized arrest of the Golden State Killer in 2018 — just four were crimes perpetrated against a Black victim. Cases solved with genetic genealogy, as a recent Atlantic article notes, “tended to be notorious crimes” that stuck in the public memory, where evidence was maintained for years and news coverage was widespread.

This racial disparity should be surprising — after all, Black people are more likely to be victims of homicide than people of other races, and are in fact more likely to experience violent crime in general.1 But the lack of “notorious” unsolved crimes involving Black victims is part of a larger American problem: the devaluing of the lives and experiences of Black, indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC), as evidenced by clear racial disparities in crime victimization.

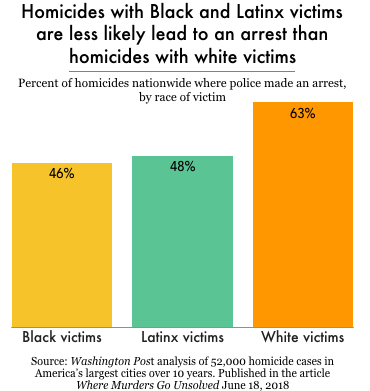

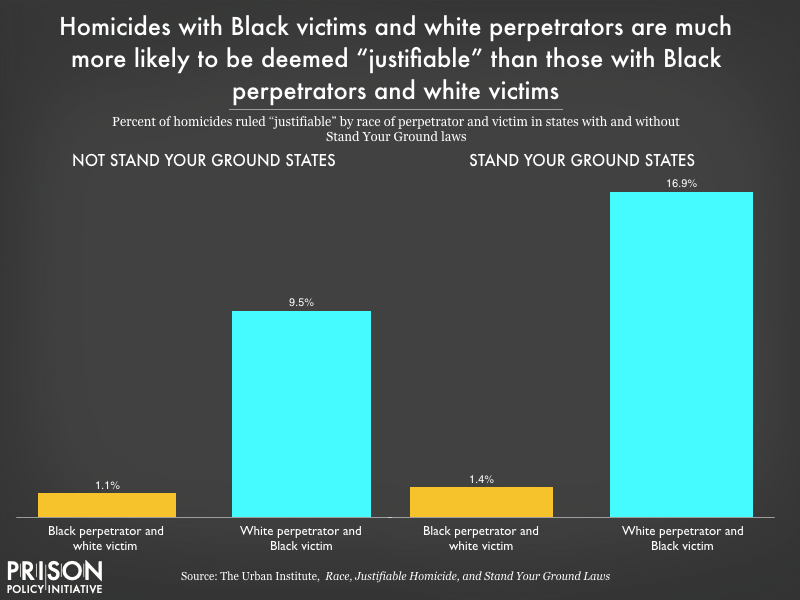

The research shows that not only are Black Americans – especially those in poverty – disproportionately victims of crime, but that crimes against Black people are less likely to be cleared by police and less likely to receive news coverage than crimes against white people. What’s more, crimes with Black victims are also more likely to be deemed “justifiable” by the courts. In this briefing, we highlight and discuss research findings about those disparities.

Crimes against Black and Latinx people are less likely to be solved

The journalists note that some of the disparity in arrest rates may stem from the fact that — due to a long history of racist policing — members of comunities of color may be less likely to trust and cooperate with police. An additional factor may be that homicides involving firearms — which are used disproportionately in murders of Black victims — are less likely to be solved, regardless of the race of the victim.2 However, these contributing factors do not explain the overall disparate experiences of violent victimization between BIPOC and white Americans.

Disparities in news coverage

Crimes against Black people are also less likely to receive media attention. A 2020 analysis of all news coverage of the 762 homicides in Chicago in 2016 found that where a crime occurred contributed to its perceived newsworthiness. Murders in predominantly Black neighborhoods received less coverage than those in white neighborhoods. What’s more, the authors noted, “Those killed in predominantly Black or Hispanic neighborhoods are also less likely to be discussed as multifaceted, complex people.” To measure this, researchers counted the number of times articles described victims in terms of their roles in the community (such as spouse, grandchild, friend, or volunteer), instead of focusing simply on the details of the crime.

The lack of media attention to crimes involving victims of color may actually explain some of the difference in police clearance rates. News coverage can help make people aware that a crime occurred, lead to information from the public, and keep pressure on police departments. For example, the media and public obsession over certain crimes, dubbed the “Missing White Woman Syndrome,” can mean less attention is given to cases of missing Black people.

Disproportionate use of Stand Your Ground laws

Even when a homicide does lead to an arrest, courts are more likely to deem homicides with Black victims “justified” than when the victims are white.

Since Florida enacted its “Stand Your Ground” law in 2005, allowing people to use lethal force if they believe they are in danger, 27 other states have passed similar statutes (an additional eight are Stand Your Ground states by legal precedent or jury instruction). In a 2015 analysis of all homicide cases in Florida from 2005 to 2013 where “Stand Your Ground” was invoked as a defense, the authors found that, after controlling for other variables, defendants were twice as likely to be convicted if the case involved white victims. Another study, which considered nationwide homicide data from 2005 to 2010, found that 11.4% of homicides with a white perpetrator and a Black victim were ruled justified, compared to 1.2% of cases where a Black person killed a white victim. This disparity existed in both states that did and did not have Stand Your Ground laws, but was greater in states with the laws.

Research shows that the cards are stacked against Black victims of crime. Not only are they more likely to experience crime in the first place, but those crimes are less likely to be publicly covered in the media and solved by police, and more likely to be ruled justified. As the authors of the analysis of homicide news coverage in Chicago noted, “Whereas the loss of White lives is seen as tragic, the loss of Black and Hispanic lives is viewed as normal, acceptable, even inevitable.”

Footnotes

-

Using data from the 2018 National Crime Victimization Survey, Anna Harvey and Taylor Mattia found that Black survey respondents were 22% more likely to experience a serious violent crime than non-Hispanic white respondents. When property crimes were included, the disparity rose to 41%. (In a similar fall 2020 report, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) did not find racial disparities in crime victimization in 2018. One major difference between the studies was that the BJS included simple assaults in its analysis, which Harvey and Mattia did not. Notably, neither study includes homicide in its analysis.) Another study found that the 2017 homicide victimization rate for Black Americans was 20.42 per 100,000, compared to 5.2 nationally. And as we know, Black people are more than twice as likely as people of other races to be killed by police, even in situations where there are no obvious circumstances that would make the use of deadly force “reasonable.”

A major contributing factor to this higher rate of violent victimization is that Black people are twice as likely as white people to live below the poverty line. A Bureau of Justice (BJS) report found that, from 2008 to 2012, both Black and white people living in households below the poverty line are more likely to experience violent victimization than those in low, middle, and high income households. And as The Guardian noted in an article mapping gun violence across the country, gun homicides are extremely concentrated in areas of high poverty, low educational attainment, and “neighborhoods forged out of racial segregation.”

↩ -

According to 2019 FBI data, 83.8% of homicides of Black people involved a gun, compared to 61.8% of homicides of white people and 73.2% of all homicides. Murders involving firearms are often more difficult to solve for a varity of reasons, including the physical distance between shooter and victim, which often leaves less evidence. Regardless of the victim’s race, police are less likely to identify the perpetrator in gun-related homicides. ↩