Untangling why prison & jail populations dropped early in the pandemic

Reductions in prison and jail populations were due to COVID-related slowdowns in the gears of the criminal legal system. Without intentional action, these reductions will be erased.

by Wendy Sawyer, March 24, 2022

- Sections

- Crime and arrests

- Jail bookings & pretrial detention

- Court slowdowns

- Prison admissions

- Keeping admssions low

Last week, we released the latest edition of our Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie report, in which we showed about 1.9 million people locked up by various U.S. systems of confinement, according to the most recent data available. Out of context, that number would be cause for celebration among those of us fighting to end mass incarceration: it’s almost 400,000 fewer people than were locked up before the pandemic. Unfortunately, this reduction in the incarcerated population is unlikely to last very long without more lasting policy change. In fact, fear-mongering about upticks in certain specific crimes may make this work even harder and lead to policy changes that make mass incarceration even more intractable.

It’s important, therefore, to understand what changes — intentional or not — led to the prison and jail population drops in 2020 and 2021. This briefing offers the context needed to temper expectations about sustaining those population drops and to maintain focus on the policy changes needed to permanently reduce the use of confinement. Without those needed changes, we can expect prison and jail populations to return to pre-pandemic “normal” (extreme by any other measure) as the criminal legal system returns to “business as usual.”

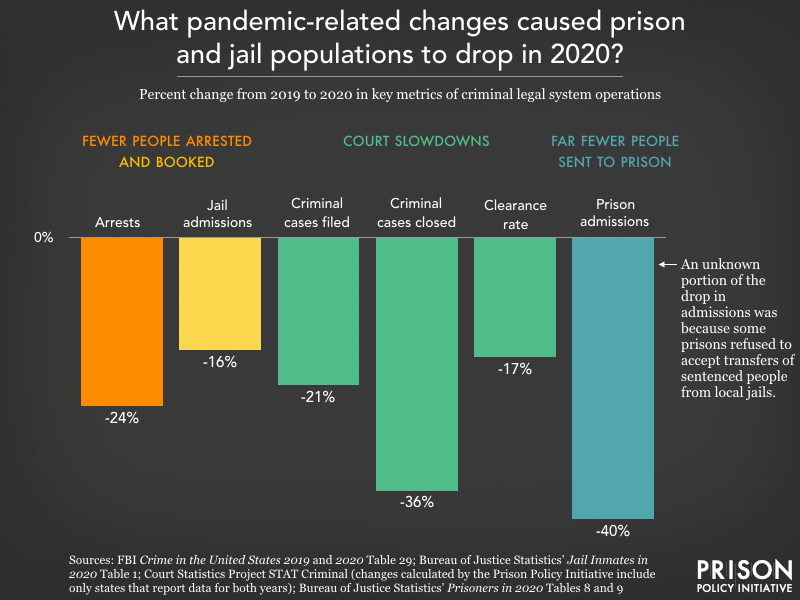

The changes that have had the most impact on incarceration since the start of the pandemic include:

- 24% fewer arrests in 2020 compared to 2019, largely due to changes in everyday behaviors under widespread “stay at home orders,” as well as short-term guidance issued by some police departments to limit unnecessary contact and jail bookings;

- 21% fewer criminal cases filed in state courts in 2020 compared to 2019 — the result of fewer arrests and changes in some prosecutorial practices;

- 36% fewer criminal cases resolved in state courts from 2019 to 2020, attributable to court closures, operational changes, and delays in case processing;

- A 17 percentage point net drop in criminal case clearance rates in state courts, indicating a growing backlog of pending cases;

- 40% fewer admissions to state and federal prisons in 2020 compared to 2019, largely the result of court slowdowns but also partly due to the refusal of some prisons to accept transfers from local jails to prevent the spread of the virus.

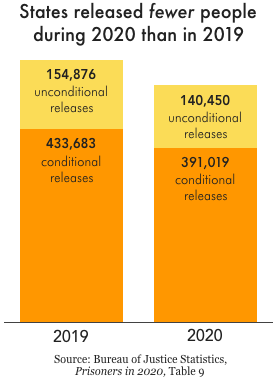

Critically, the one thing that we and other advocates demanded from the very start of the pandemic – intentional, large-scale releases to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the tight quarters of prisons and jails – did not happen. In the first year of the pandemic, prisons actually released 10% fewer people than they did the year before, and among the twelve states that regularly publish more recent data, that trend held throughout 2021 as well. Only three states (New Jersey, California, and North Carolina) released a significant number of incarcerated people from prisons. Parole boards also approved fewer releases in the first year of the pandemic than the year before.

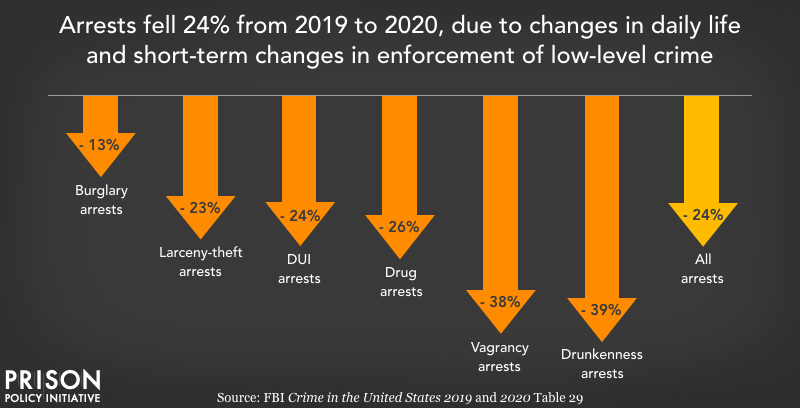

Changes in crime and arrests

Two major factors contributed to the 24% drop in arrests in 2020: widespread changes in behavior and more limited changes in police practices. The shift away from in-person activities towards remote work, learning, commerce, and social contact represented a major change in our usual behaviors. This explains some changes in crime trends: for example, with more people home during work hours and on weekends, there were fewer low-risk targets for home break-ins. And in 2020, there were 18% fewer home burglaries reported than in 2019, and consequently 13% fewer arrests for burglary. With fewer people out, there were also fewer opportunities for thefts that require close contact: reports of pickpocketing dropped 37% and purse-snatching 25%, and arrests for these types of crimes (larceny/theft) dropped 23%. The 24% drop in arrests for driving under the influence (DUI) also makes sense in this context: there were fewer people on the roads, and for a long time, few bars or restaurants open for people to consume alcohol.

Policing changed too, to a lesser degree. Police officers got sick, reducing their capacity to arrest, and some officials directed police to avoid unnecessary contact with the public and to issue more citations in lieu of arrest. This likely explains the dramatic reductions in arrests for “nuisance” crimes like vagrancy and drunkenness.

Some of these changes were extremely short-lived: Philadelphia police suspended “non-violent” arrests in mid-March 2020, but just two weeks later, the police force announced it would resume arrests for property crimes, effectively reversing the earlier policy. Police in Maui, Hawai’i set up a call center early in the pandemic to handle calls that didn’t require in-person responses; it was shut down within just three months, when the Police Chief declared “things are settling down.”

Given that almost all of these changes were in direct response to the pandemic, as opposed to long-term policy changes, we should anticipate a return to pre-pandemic arrest rates as work, school, business, and social life return to “normal.”

Jail bookings and pretrial detention decisions

Jail admissions generally mirror arrest trends, so fewer arrests mean fewer people booked into jail. The drop in arrests in 2020 therefore accounts for most of the 16% drop in jail admissions over the course of the year. But there were also some notable, temporary, pandemic-response policies that contributed to the reduced jail populations we saw in 2020, namely:

- The promises of many prosecutors to decline to prosecute certain low-level offenses or to dismiss pending charges against people arrested for such offenses,

- The suspension of arrests for non-criminal (or “technical”) violations of probation and parole,

- Temporary changes in probation and parole conditions that made it easier for people under community supervision to comply, such as videoconferencing instead of face-to-face check-ins and the waiving of monthly fees, and

- The temporary suspension of arrests on outstanding “bench warrants” for things like missed court dates.

Some courts and prosecutors also made impactful, though temporary, changes to pretrial processes. On any given day, at least two-thirds of the nation’s jails are filled with people who have not been convicted and are legally innocent, many because they cannot afford money bail. But early in the pandemic, we saw changes like the “$0 bail” emergency rule ordered for California’s courts, which eliminated unaffordable bail as a barrier to pretrial release for people accused of misdemeanors and lower-level felonies. In another example, the State’s Attorney in Vermont’s largest county directed her office to stop requesting bail for defendants facing low-level charges.

Together, these changes reduced the use of jails for things other than serious public safety concerns. Most of these temporary policies have long since expired, so, except for those places that have enacted policies to permanently reduce incarceration for these non-dangerous and/or non-criminal violations, we should expect to see more people jailed for these reasons again as the pandemic wanes.

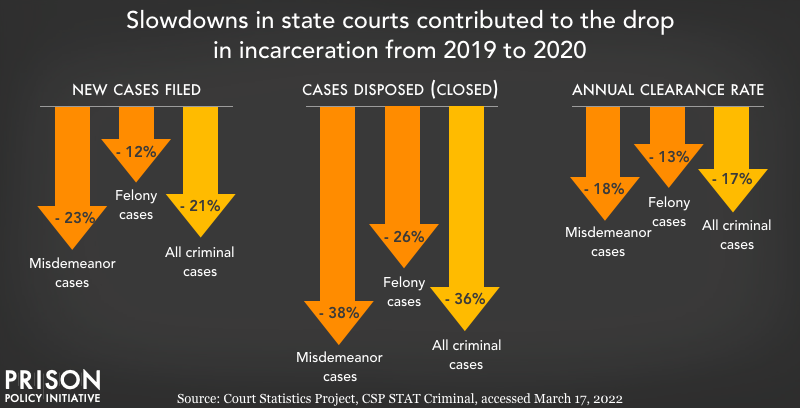

Court slowdowns

Most courts had to dramatically change their operations during the pandemic in ways that led to long delays in case processing. According to the National Center for State Courts, the most common court responses to the pandemic included restricting or ending jury trials, suspending in-person proceedings, restricting entry to courthouses, extended filing deadlines, and encouraging video conferences in place of hearings.

In 2020, 21% fewer criminal cases were filed in state courts than in 2019, which in turn meant fewer people were convicted and sentenced to jail or prison. The most recent data available indicates that the number of criminal case filings were still much lower than pre-pandemic levels as of June 2021. Some of this drop in new cases is explained by changing crime and arrest trends, but prosecutorial decisions also played a key role. For example, the Maricopa County (Arizona) Attorney’s Office began delaying the filing of – but not dismissing – “thousands of charges” in an effort to keep down the number of people in courtrooms and jails (and potentially to avoid problems complying with speedy trial laws). And Seattle’s District Attorney decided early on to briefly stop filing charges except for “priority in-custody violent crimes.”

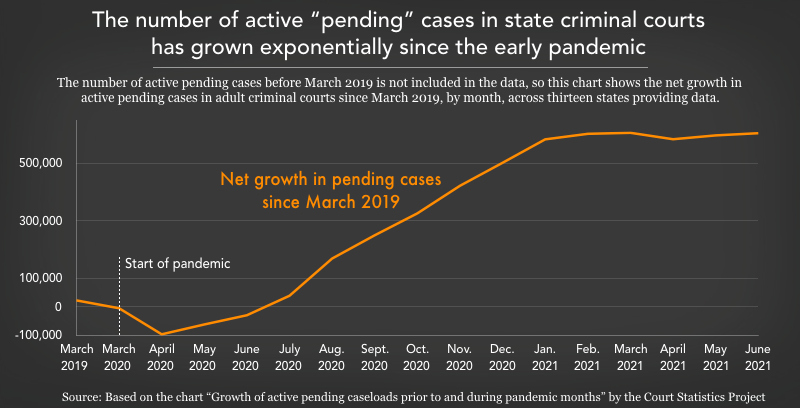

But the changes in court operations have made an even bigger dent in case dispositions than case filings: in 2020, state courts closed 36% fewer criminal cases than in 2019. Unable to keep pace with incoming cases, the clearance rate for criminal cases across over 30 state court systems dropped from 105% in 2019 (when courts were able to close more cases annually than were added to the docket) to 88% in 2020. Some of this slowdown, too, was the result of attorneys requesting postponements; some was simply due to court closures.

Pandemic caseload data from the Court Statistics Project show that criminal court slowdowns were at their worst between July 2020 and January 2021, but even with fewer new cases coming in, “pending” cases have piled up and will take time to clear. As they do, and as arrests and prosecution return to pre-pandemic norms, we can expect the rate of people convicted and sentenced to incarceration to climb back up.

Prison admissions

The cumulative effect of fewer arrests, temporary changes in probation and parole practices, and pandemic-related delays in trials and sentencing was a dramatic 40% reduction in the number of people who entered prisons in 2020. The number of new court commitments (that is, people admitted to prison to serve a new sentence) dropped almost 43% from 2019 to 2020. And, for the same reasons jail admissions fell for non-criminal violations of probation and parole, the number of people admitted to prisons for these violations fell 35%. The massive decrease in admissions was driven by steep drops in large states like California (down 66%), Florida (down 53%), and New York (down 60%).

Some of the change in admissions to prison, however, was simply because people were left in jails longer before being transferred to prisons. In an effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19 between facilities (a very valid concern), some state prison systems, such as Illinois’, refused to admit people held in local jails who were sentenced to prison. While this may have helped slow the spread into prisons, staff were still bringing the virus into facilities from their home communities. Meanwhile, these delays left thousands of people stuck in local jails, which have fewer programs and far more population turnover than prisons – a miserable situation at any time, but particularly during a pandemic.

Again, because the changes that resulted in fewer admissions in 2020 were temporary responses to the pandemic, we should expect prison populations to rebound to pre-pandemic levels as courts catch up with their backlog of pending cases and probation and parole agencies return to more stringent conditions and harsher punishments for non-criminal violations.

Prison and jail admissions are at historic lows. We can keep it that way.

The changes to the criminal legal system during the pandemic were, for the most part, temporary responses to the immediate public health emergency, not deliberate policy choices to reduce incarcerated populations over the long term. There is little reason to think that incarceration rates will remain at their pandemic-era lows without more intentional changes, particularly since jail and prison populations have already started to rebound. Furthermore, the piecemeal actions that federal, state, and local authorities did take were not nearly enough to protect people in prisons and jails, nor the communities that surround them. To date, almost 600,000 incarcerated people have been infected and more than 3,000 have died behind bars because of COVID-19. And of course, the pandemic isn’t over; still, authorities continue to ignore public health guidance that specifically calls for decarceration.

The fact that many early-pandemic policy changes were so short-lived is particularly frustrating since we know they helped rapidly reduce populations without compromising public safety. Data from the National Crime Victimization Survey show that the number of violent crimes (excluding homicide, which the survey does not cover) fell from about 2 million in 2019 to 1.6 million in 2020; accordingly, the rate of violent victimization fell by 22%. The household property crime victimization rate fell by about 7%. And, as discussed above, arrests and crimes reported by police fell, too.

Government authorities’ willful disregard of the evidence that further, sustained policy changes are both urgently needed and safe is part of a larger problem, of course. The perception (not a reality) that criminal justice reforms have led to upticks in crime over the past few years has fueled pushback against smart policy changes. That perception is powerful, and history shows that reactionary policies can follow: In the 1980s and 1990s, the last time prison and jail populations were as low as they were in 2020, the knee-jerk reaction to (much bigger) increases in crime was to lock more people up, and for longer. Particularly in the context of the ongoing pandemic, we can’t afford to let that happen again.