Why states should change Medicaid rules to cover people leaving prison

People leaving prison have sky-high mortality rates. Most are likely Medicaid-eligible. Making sure they are covered upon release from prison would save lives and reduce recidivism.

by Emily Widra, November 28, 2022

The gap in healthcare coverage following incarceration leads to high rates of death just after release: During just the first two weeks after release from prison, people leaving custody face a risk of death more than 12 times higher than that of the general U.S. population, with disproportionately high rates of deaths from drug overdose and illness. A huge contributing factor to this astronomically high death rate following release is the healthcare coverage gap: People lose health insurance coverage while in jail or prison and their lack of coverage continues post-release, leaving many without access to adequate, timely, and appropriate health care in those critical first weeks of reentry.

Fortunately, we have a way to address this healthcare coverage gap, and to improve the health and safety of our communities in general: Medicaid. Research shows that expanding access to healthcare through Medicaid saves lives and reduces crime and arrest rates — along with state spending — making this a reform strategy whose time has come.

How Medicaid’s “inmate exclusion policy” leaves formerly incarcerated people without healthcare

When Medicaid was authorized in 1965, the “inmate exclusion policy” was established to prevent state and local governments from receiving matching federal funds to cover the healthcare costs of people in state prisons and local jails. This policy leaves state and local governments solely responsible for financing the healthcare of incarcerated people, 1 even when those people were covered by Medicaid prior to their incarceration. This means that in most states, Medicaid coverage is terminated when someone is incarcerated. 2

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (the federal agency responsible for Medicare and Medicaid) has advocated that people be returned to the Medicaid eligibility rolls “immediately upon release from a correctional facility,” and has even provided resources to correctional systems, probation officers, and parole officers to help make this happen. Nevertheless, as things stand now – despite most people being financially eligible for Medicaid upon release – connecting with appropriate healthcare providers and reapplying for Medicaid is no easy feat for people going through reentry, leaving too many medically vulnerable and disconnected from healthcare services in the community.

Most incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people are probably eligible for Medicaid

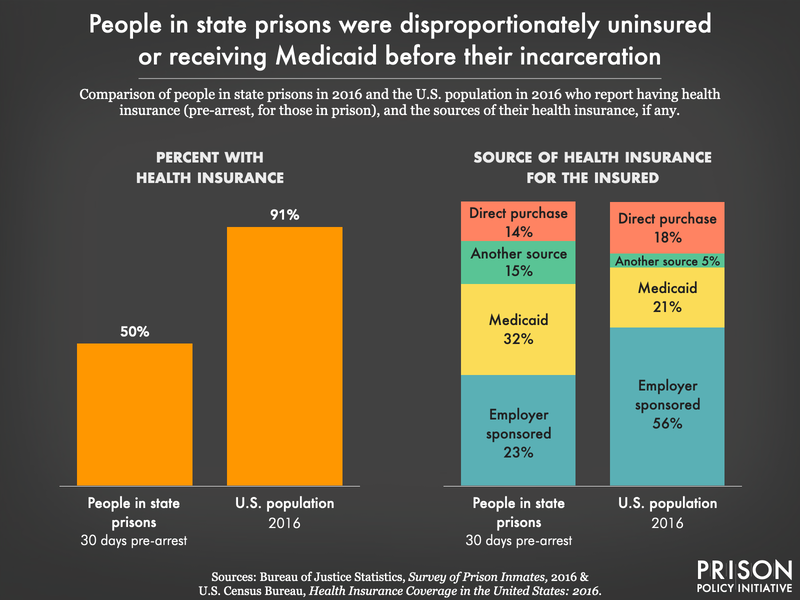

In all states, Medicaid provides health coverage for low-income people who qualify based on income, household size, disability status, and a handful of other factors. Most people in contact with the criminal legal system are likely eligible for Medicaid: People in prisons and jails are among the poorest in the country and have high rates of disabilities, making them likely eligible for Medicaid in almost every state. People in contact with the criminal legal system have drastically lower pre-incarceration incomes than people who are never incarcerated. In fact, 32% of people in state prisons in 2016 who had insurance at the time of their arrest were covered by Medicaid (compared to about 19% of insured people nationwide). As an additional indicator of need among this population, 50% of people in state prisons were uninsured at the time of arrest.

Formerly incarcerated people face low incomes and high rates of unemployment, meaning that they too are likely to be eligible for Medicaid, especially in states where Medicaid eligibility is based solely on income. After incarceration, people experience unemployment at high rates and report low incomes. Formerly incarcerated people are unemployed at a rate of over 27%, which is higher than the total U.S. employment rate during any historical period, including the Great Depression. When formerly incarcerated people do land jobs, they are often the most insecure and lowest-paying positions: the majority of employed people recently released from prison receive an income that puts them well below the poverty line.

Excluding justice-involved people from Medicaid can be lethal

People in prison have higher rates of certain chronic conditions and infectious diseases, disabilities, and face exceptionally high rates of mental illness compared to the general U.S. population, but medical and mental health care in prisons and jails are grossly inadequate. 3 As a result of such inadequate healthcare, many people in prison end up worse off upon release. Subpar healthcare behind bars and the post-release healthcare coverage gap are pivotal factors in the heightened risk of death after release.

The risk of death is particularly high in the first two weeks following release from prison (12 times higher than the general population), but the lethal consequences of incarceration continue beyond these first two weeks. A 2021 study found that high county jail incarceration rates are associated with high mortality rates, but most acutely with deaths by infectious disease, respiratory disease, drug overdose, suicide, and heart disease. In 2019, a study of people released from North Carolina prisons found that people who spent any time in solitary confinement 4 were 24% more likely to die in the first year after release (with an extraordinarily high risk of death from opioid overdose in the first two weeks after release). Another study found that people in their sample who were released from prison were twice as likely to die within 30 days and 90 days of release than those who were not incarcerated.

Uninsured people are less likely to seek medical care - because of the financial costs - and when they do seek out care, that care is often too late or of poor quality, resulting in worse health outcomes and higher rates of death.Many of these deaths following release are preventable with appropriate medical, mental health, and substance use interventions, which usually require health insurance. But because people are released from prisons and jails without insurance, they are less likely to receive the necessary interventions upon release. Uninsured people are less likely to seek medical care (because of the financial costs), and when they do seek out care, the care is likely of poor quality or too late, resulting in worse health outcomes and higher rates of death when compared to insured people.

How states can reform Medicaid to cover people leaving prison

A number of states have utilized Medicaid to start to bridge the healthcare coverage gap, and there are encouraging results. Given that some of the predominant healthcare-related concerns among recently-released people include lack of insurance and difficulty accessing care and medication, bridging this gap is a crucial step to mitigating the harms caused by barriers to healthcare services.

Reduce barriers to Medicaid eligibility

In a handful of states, Medicaid coverage is expanded to allow people to qualify based solely on finances (with an income below 133% of the federal poverty line). In these states, there are now fewer barriers to Medicaid eligibility, and therefore more people receiving Medicaid. While this reform does not exclusively target people leaving prison, it benefits them: Following Medicaid expansion in New York and Colorado, state officials estimated that 80-90% of people in state prisons would now be eligible for Medicaid coverage upon release (based on their pre-incarceration incomes).

Enroll people in Medicaid before their release from prison

Oklahoma began a program in 2007 to help people in prison with severe mental illness apply for Medicaid benefits during their final months in prison. This program had quick results: after one year, the share of people who were enrolled in Medicaid on their day of release increased by 28 percentage points.

A 2022 study of Louisiana’s Prerelease Medicaid Enrollment Program found that there was a 34.3 percentage point increase in Medicaid enrollment, and of those who were successfully enrolled before release, 98.6% had attended at least one outpatient visit within the first 6 months of release. These findings – along with similar programs in other states – suggest that pre-release Medicaid enrollment programs are a relatively simple way to connect people to necessary healthcare services and bridge the healthcare coverage gap.

In Connecticut and Massachusetts, there are statewide programs that enroll all Medicaid-eligible people who are being released from prison to parole. While incarcerated and waiting for their release date, incarcerated people work with “discharge planners” in correctional facilities to complete and submit Medicaid applications that are then held by the state’s Medicaid agency until they are released on parole. In Massachusetts, the state reports that 90% of people released to parole are covered by Medicaid upon their release.

Suspend – rather than terminating – Medicaid coverage for incarcerated people

In twelve states, 5 Medicaid coverage is suspended – rather than terminated – when someone is incarcerated in state prison, which makes the process of reinstating Medicaid coverage upon release much simpler and avoids the need for “discharge planners” to help with applications or make other arrangements. In Maricopa County, Arizona, an agreement with the state Medicaid agency allows Medicaid eligibility to be suspended – not terminated – upon jail incarceration in the county.

Request federal Medicaid waivers

States can petition the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to waive federal guidelines 6 to allow states to trial new approaches and pilot new policies. 7 At least nine states – Arizona, California, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Montana, New Jersey, Oregon, Utah, and Vermont – have submitted requests for waivers to modify the “inmate exclusion policy” and allow for coverage of certain health services provided pre-release. The proposals vary in what incarcerated populations they are seeking eligibility for, what services they would like to be Medicaid-eligible prior to release, and when coverage would be offered. Some states are seeking eligibility for a specific group of incarcerated people, such as four behavioral health case management visits for those with behavioral health diagnoses (New Jersey) or specific substance use disorder treatment services for incarcerated people with substance use disorders (Kentucky). Other states are seeking the full set of Medicaid benefits for incarcerated people with chronic conditions (Massachusetts) or for all incarcerated people (Utah). As of March 2022, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had not yet issued decisions on any of these proposals.

A bill in Congress would allow Medicaid coverage for people leaving prison or jail

In 2021, members of the House of Representatives introduced the Medicaid Reentry Act. This bill would allow Medicaid coverage to begin 30 days before people are released from prisons or jails, allowing medical services during that time period to be covered by Medicaid and for people to be insured the moment they are released from the facility. Legislation like this would vastly expand access to healthcare after incarceration, closing the dangerous healthcare coverage gap and thereby reducing the preventable deaths and health problems that occur in the immediate post-release period.

Other benefits of closing the healthcare coverage gap

The effects of bridging the healthcare coverage gap are far more expansive than one might expect. Increasing access to healthcare appears to have significant effects on reducing arrests, crime rates, criminal-legal system involvement, recidivism, and state expenditures.

Reducing arrests and lowering crime rates

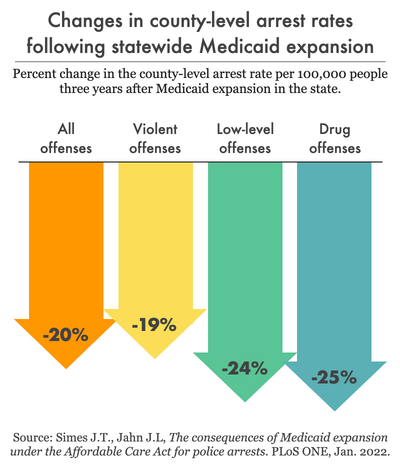

In states with Medicaid expansion (i.e., where eligibility is based solely on income), there have been correlated reductions in crime rates and arrests. Compared to counties in states that had not implemented expanded Medicaid coverage, counties in states with Medicaid expansion saw a 25% decrease in drug arrests, a 19% decrease in “violent offense” arrests, and a 24% decrease in “low-level” offense arrests. 8 Looking at more specific types of crimes, researchers also found a 3.7% to 7.5% decrease in burglary, motor vehicle theft, robbery, and violent crime rates in counties with statewide Medicaid expansion. 9

Preventing contact with the criminal-legal system

By investing resources in healthcare and expanding Medicaid coverage to as many people as possible up front, we can actually begin to reduce our reliance on the carceral system.In 1990, the federal government expanded Medicaid to provide coverage for more children and families living below the federal poverty line. Research shows that the expanded Medicaid eligibility among youth actually reduced the incarceration rates in Florida: there was a 3.5% reduction in incarceration for each additional year of population-level Medicaid eligibility. These results suggest that by investing resources in healthcare and expanding Medicaid coverage to as many people as possible up front, we can actually begin to reduce our reliance on the carceral system.

Reducing recidivism

Increased access to healthcare through Medicaid coverage also reduces recidivism. Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), there were eligibility requirements that restricted Medicaid eligibility for formerly incarcerated people, but with expanded Medicaid coverage, most previously incarcerated people who meet the necessary income criteria are eligible for Medicaid. A study published in 2022 found that expanded Medicaid coverage resulted in significant reductions in the rate of rearrest, with a 16% reduction in arrests for violent crime for two years following release.

Reducing state expenditures

The direct costs of incarceration are immense: it costs more than $225 to incarcerate someone in New York county jail for a single night and nationally, it costs an average $31,307 a year to incarcerate a single person in state prison. Meanwhile, 2019 estimates suggest that total annual Medicaid spending per person ranged from a low of $4,970 in South Carolina to a high of $12,580 in North Dakota, suggesting that even where Medicaid is spending the most per person, it is far less expensive than incarceration. While these are just rough estimates of the per capita costs of incarceration and Medicaid coverage, more in depth research implies substantial cost reductions by expanding Medicaid coverage to all Medicaid-eligible formerly incarcerated people. The estimated costs of expanded Medicaid coverage – by reducing the economic and social costs of victimization and the expenditures on multiple incarcerations – are significantly less than state and local governments are currently spending on arrest, jail, court, and imprisonment.

Conclusion

The healthcare coverage gap that threatens the lives of people recently released from prison is not inevitable. Incarcerated people and those released from incarceration face poverty, unemployment, and disproportionately high rates of disability, disease, and illness, but Medicaid is a tool we can use to expand healthcare coverage and reduce the number of preventable deaths after release. Evidence from states with these kinds of Medicaid programs in place suggests that hundreds of thousands of people being released across the country each year would benefit from such efforts. Expanding access to affordable, quality healthcare results in a myriad of benefits to public health, public safety, and public coffers. Perhaps most encouragingly, the drop in arrests and crime following expanded Medicaid coverage offers evidence that by ensuring people’s most basic needs are met, we can begin to reverse our nation’s reliance on mass incarceration.

Footnotes

-

Medicaid does currently provide coverage for incarcerated people (who would otherwise qualify for Medicaid) only if they are hospitalized outside of the correctional facility for 24 hours or longer. ↩

-

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, federal law does not require states to terminate Medicaid eligibility status for inmates, but it does prohibit states from obtaining federal matching funds for services provided to people while in jail or prison. But many states do terminate Medicaid eligibility status upon incarceration: according to a 2014 study of 42 state prison systems, individuals on Medicaid are completely removed from their insurance system upon incarceration in two-thirds of these states. ↩

-

Among incarcerated people with persistent medical problems, 20% of those in state facilities and 68% of those in local jails went without any sort of medical care during their incarceration. Over half of people in state prison in 2016 reported mental health problems, but only a quarter had actually received professional mental health help since admission. ↩

-

The phrase “solitary confinement” is not used consistently. Some prisons deny that they employ it, instead opting for more administrative-sounding terms, like “Segregated Housing Units” (SHUs) and “restrictive housing.” (See this list from MuckRock for more examples.) While conditions can vary between facilities, for our purposes, “solitary confinement” refers to the practice of segregating individuals from the general population for any reason. Under solitary confinement, individuals are typically forced to remain in small, individual cells for 22 to 24 hours per day with minimal human interaction. ↩

-

California, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Texas and Washington. ↩

-

These are often referred to as “1115 Medicaid waivers” and are depicted in federal Medicaid law as a “Section 1115 demonstration.” ↩

-

A good example of how states have used Medicaid waivers in the past is the Coordinated Care Organization program in Oregon. The state received a waiver to create partnerships between managed care plans and community providers to manage health-related services not previously covered by Medicaid, like short-term housing following hospital discharge, home improvements to allow people to remain in the community, and efforts to reduce preventable hospitalizations. ↩

-

In this study, arrests for “violent offenses” include murder, manslaughter, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault, “drug offenses” include sales and possession, and “low-level” offenses include disorderly conduct, prostitution, suspicion, vagrancy, vandalism, drunkenness, driving under the influence of substances, and possession of stolen property or weapons. ↩

-

The two studies cited here controlled for other factors, including age, unemployment, poverty, and race. ↩