Eligible, but excluded: A guide to removing the barriers to jail voting

While people in state or federal prison generally cannot vote, most people in local jails can, although numerous barriers prevent them from doing so.

by Ginger Jackson-Gleich and Rev. Dr. S. Todd Yeary

Press release

October 2020

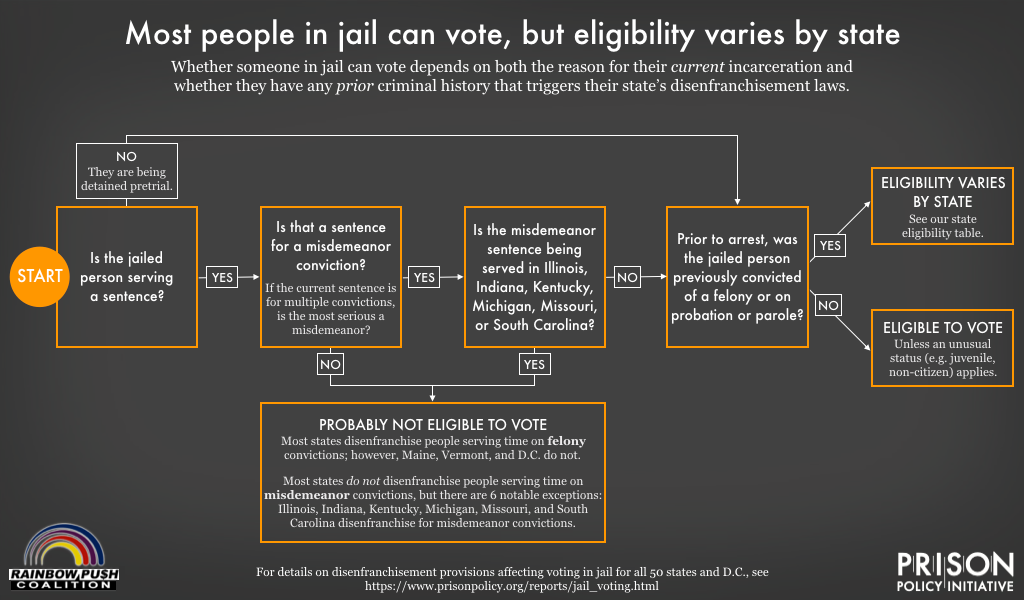

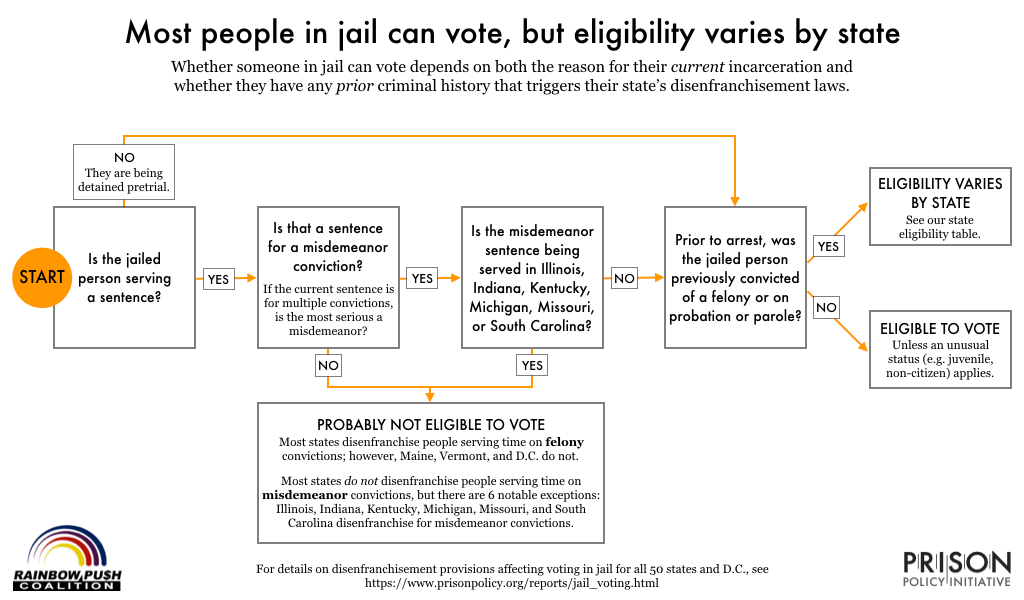

Most people in jail1 are legally eligible to vote, but in practice, they can’t. This “de facto disenfranchisement” stems from numerous factors, including widespread misinformation about eligibility, myriad barriers to voter registration, and challenges to casting a ballot. Below, we explain who in jail is eligible to vote (state by state), discuss the barriers that keep them from voting, and offer recommendations for advocates, policymakers, election officials, and sheriffs to ensure that people in jail are able to vote.

Who in jail can vote?

Put simply, of the approximately 746,000 individuals in jail on any given day, most have the right to vote.2 This is the case for several reasons:

- Most people in jail have not been convicted of the charges on which they are being held (i.e. they are being detained “pretrial”), and pretrial detention does not disqualify someone from voting.

- People in jail who are serving post-conviction sentences have typically been convicted of only minor offenses called misdemeanors, and very few states disenfranchise people serving time for misdemeanor convictions.

- Although some people in jail may be disenfranchised for reasons independent of their current detention (e.g. a prior felony conviction or being on probation/parole in a different case), not all states disenfranchise people on probation or parole (see table below), and the number of people who are in jail while also on probation or parole is relatively small.

| Does the nature of a person’s current detention impose barriers on voting eligibility? | Do any prior criminal convictions separately impose barriers on voting eligibility? | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detained pretrial | Serving misdemeanor sentence | Serving felony sentence | Currently on felony probation | Currently on parole | Prior felony conviction | |||

| Alabama | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier* | Barrier* | Barrier* | Barrier* | ||

| Alaska | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Arizona | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

| Arkansas | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| California | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Colorado | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Connecticut | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Delaware | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

| Florida | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

| Georgia | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier3 | Barrier4 | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Hawaii | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Idaho | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Illinois | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Indiana | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Iowa | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier5 | ||

| Kansas | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Kentucky | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

| Louisiana | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | Barrier* | No Barrier | ||

| Maine | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Maryland | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Massachusetts | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Michigan | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Minnesota | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Mississippi | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier* | Barrier* | Barrier* | Barrier* | ||

| Missouri | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Montana | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Nebraska | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

| Nevada | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| New Hampshire | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| New Jersey | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| New Mexico | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| New York | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier* | No Barrier | ||

| North Carolina | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| North Dakota | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Ohio | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Oklahoma | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Oregon | No Barrier | Barrier6 | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Pennsylvania | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Rhode Island | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| South Carolina | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| South Dakota | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Tennessee | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

| Texas | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Utah | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Vermont | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Virginia | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

| Washington | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Washington, D.C. | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier7 | No Barrier | No Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| West Virginia | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Wisconsin | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | No Barrier | ||

| Wyoming | No Barrier | No Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier | Barrier* | ||

Barriers that keep jailed voters from voting

Most people in jail are legally eligible to vote, but they are prevented from doing so by numerous barriers.

One of the biggest barriers: confusion about eligibility

One of the biggest barriers to voting in jail is the fact that local election officials often don’t know that most people in jail can vote, and it’s not unusual for such officials to provide incorrect information in response to questions about the issue.8 The spread of inaccurate eligibility information can also occur when registration forms contain incorrect, confusing, or incomplete information about criminal disenfranchisement laws. Given that election officials and election materials can be wrong, it should be no surprise that people working at and detained in jails are frequently confused about eligibility as well.

Registration-related barriers

Even when someone knows they are eligible to vote, numerous obstacles still stand in the way of doing so, beginning with the myriad obstacles to registering to vote from jail:

- Registration Deadlines: In 30 states, people wanting to vote must register days or weeks in advance of Election Day. A person who is incarcerated through the registration period and cannot register from jail may end up foreclosed from voting.

- Voter ID Laws: Some states have strict voter ID laws requiring particular forms of identification to register to vote. Not only are people in jail less likely to have the required types of identification, but when people are arrested, their personal effects — including IDs — are typically confiscated. In addition, government-issued prison or jail ID cards do not typically qualify as accepted forms of identification. Without appropriate identification, jailed voters wishing to register may not be able to do so.

- Limited Access to Registration Forms: Voter registration often requires completion of official forms that may be filled out either online or on paper. Because people in jails typically lack access to the internet and to paper election forms, it can be impossible to submit the required registration documents.

- Limited Access to Personal Information: Some states require first-time registrants to provide their social security number or driver’s license number,9 something that many people (especially young people, who may be more likely to be first-time voters) do not have memorized.

- Jail Mail Delays: Typically, registration forms must be received by election offices by strict deadlines, which means that incarcerated people who rely on the jail’s mail system or in-jail volunteers for submission of their forms must complete required registration paperwork even further in advance.

- Common Safeguards Can’t Be Accessed from Jail: Mechanisms that enable people to check their registration status and ensure that they have been designated an eligible voter are essential to protecting against improper or illegal disenfranchisement (both within and outside of jails). However, utilization of such mechanisms can be difficult (or impossible) from jails, where people lack internet access and where the cost of phone calls may be prohibitively expensive.

Ballot-casting barriers

Many of the above-mentioned barriers to registration also arise in the context of actually casting ballots. These include early deadlines (particularly with respect to absentee ballot procedures); requirements that IDs be presented or that absentee ballots be notarized; incarcerated people’s limited access to voting forms, election resources, and their own personal information and/or documents; and the difficulty of confirming that a ballot has been received and/or accepted by election officials. Delays in jail mail may also impede the timely casting of ballots.

Barriers to obtaining and submitting ballots also include:

- For-Cause Absentee Voting Policies: In 16 states,10 voting by absentee ballot is only permitted when a voter claims one of a short list of recognized justifications. In most of these states, detention in a jail is not a recognized justification, so in these states people in jail are de facto barred from casting a ballot.

- Fear of Compromised Ballot Secrecy: Where “all non-privileged outgoing mail may be read by custody staff,” incarcerated people may rightly worry about the secrecy of any ballots mailed from jails. Additionally, because most sheriffs are elected and will be on the ballot periodically, issues of ballot secrecy may also generate concerns about retaliation or ballot tampering that dampen turnout in jails.

- Limited Access to Voter Guides: Many states (and some counties) publish voter guides that are sent to all residential addresses. However, these guides may not be distributed to jails, either because policies do not require such distribution or because such policies are not enforced.

Population churn in jails

The average jail stay is between three and four weeks, with many people incarcerated for much shorter periods of time (leading to high population-turnover rates, a phenomenon known as jail churn). Consequently, some people may register to vote while free, but end up in jail on Election Day (or for the duration of the voting period). Conversely, some people may register to vote in jail, but end up released prior to casting a ballot. In either scenario, a person’s registration information will not match their status on Election Day, and these people frequently find that they are unable to vote.

Solutions

The specific work that needs to be done to enable eligible voters to cast their ballots from jail depends on the state in which they are located and the laws of that state. But in all states, there are opportunities for a wide range of actors to contribute to enfranchisement efforts.

Strategies for advocates

- Do outreach to local election officials and sheriffs about the voting rights of people in jail, as discussed in this helpful advocacy guide from the Campaign Legal Center.

- Review election resources (e.g. websites and official brochures) to ensure that clear, accurate, and comprehensive information about all forms of criminal disenfranchisement laws is included; see this ACLU report for a summary of common registration-form problems and potential solutions.

- Conduct voter registration drives in jails, and empower jailed people to vote in jail-based polling stations (as in Chicago), or to access absentee ballots where in-person voting is not available (as this doctor is doing in South Carolina and this California Public Defender’s Office is doing in English and Spanish).

- Evidence shows that where people directly assist incarcerated voters with registration and voting, voter turnout far exceeds instances in which ballots are merely dropped off at a jail; in addition, in-person drives can help to remove barriers related to literacy and language accessibility.

- Because some states permit pre-registration of 16- and 17-year-olds, and because some juvenile facilities may hold people 18 and older, advocates may want to include juvenile facilities in their efforts.

- Provide training for any election workers or volunteers that will visit the jail to ensure compliance with jail rules and cultural competency in interacting with incarcerated people.

- Monitor/provide outside support (e.g. hotlines) for jail-voting processes, as community groups have done in several states (see the instructive examples discussed by the Sentencing Project’s report “Voting in Jails” for more detail).

- Identify, publicize, and change laws, policies and practices that impede jail voting, as advocates have done in places like Arizona, Wisconsin, and Massachusetts.

- Utilize public records requests to collect information about existing jail-voting policies and procedures, as well as about the number of ballots being requested and cast by people voting from jail.

Strategies for leaders of state legislative and executive branches

- Designate jails to be formal voter registration agencies under Section 7 of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA),11 as Rhode Island has done with its Department of Corrections and Washington, D.C. has done with its jails.

- Require coordination between jail and election officials to ensure that eligible jailed voters have an opportunity to register and vote (as Colorado has done).

- In states where a voter must show ID to register or cast a ballot, states can abolish such ID requirements or add IDs provided by federal, state or local correctional facilities to the list of valid forms of identification.

- In states that require voters to register days or weeks prior to Election Day, states can change their laws to match those in 19 states and D.C. that currently allow same-day registration on Election Day.12

- In the 16 states that require a specific reason to vote absentee, states can change their laws to permit “any reason” absentee voting or add incarceration as an accepted reason.

- Permit jailed voters to request and submit absentee ballots up through Election Day.

- Appropriate funds for postage, so that registration forms, ballot applications, and ballots submitted by mail (either from jails or from any address) may be mailed without a stamp.

- Where a jailed person has requested that an absentee ballot be sent to the jail, permit anyone released from jail prior to receiving their ballot to submit a “registration affidavit” at their local polling station and vote there. (Many states already allow people who requested, but did not receive, absentee ballots to vote in person using registration affidavits.)

- Permit unhoused people to use the jail or a prior shelter as their registration address.

Strategies for election officials

- Ensure all state and local election staff know the law so that they do not incorrectly discourage jailed individuals from voting by spreading misinformation.

- Include clear, accurate, and comprehensive information about felony- and misdemeanor-based disenfranchisement laws anywhere information about eligibility is provided (e.g. on election websites and in registration pamphlets/brochures).

- Include information about jail voting in election manuals.

- Work with sheriffs to make jails polling stations (ideally voting machines/ballot boxes will be present and available at the jail on Election Day—rather than at a date beforehand—to maximize the number of people who can utilize them).

- Work with sheriffs to coordinate registration and voting via absentee ballots from jails; this should include providing opportunities for jailed voters to be notified of and to cure any deficiencies on their registration forms, ballot applications, ballot envelopes, etc.

- Where internet access is not available in jails or where online registration is not available generally, allow registration forms or requests for absentee ballots to be submitted via scanned email or fax (or work with sheriffs to provide paper forms at the jail).

- Consider operating from the presumption that people in jail can vote by providing voting materials to all incarcerated people, as has been done in some prison contexts (while also being mindful that penalties may exist for those who vote while ineligible and that confusion about eligibility can be widespread).

- If a government agency produces a voter guide, ensure distribution to jailed voters.

Strategies for sheriffs

- In states where jails have not yet been designated as formal voter registration agencies under Section 7 of the NVRA, local jails can provide voter registration materials within the jail and at various points during the admission and/or release process.

- This may include providing registration and election information on closed circuit televisions, bulletin boards, kiosks, or wherever general information is shared.

- Work with election officials to make jails polling stations (as noted above: ideally voting machines/ballot boxes will be available at the jail on Election Day—rather than on a date beforehand—to minimize the chance that someone arrested after ballot boxes have been removed but prior to Election Day would be disenfranchised).

- Work with election offices to coordinate registration and voting via absentee ballots from the jail; jails can also give election-related mail expedited treatment to ensure compliance with election deadlines.

- In places where anyone registering voters must be trained, sheriffs can ensure that their staff members are so trained.

Conclusion

The barriers facing incarcerated voters are numerous, and legislative and executive leaders have often been slow to address them. In addition, the difficulties of voting from jail are compounded by the fact that jail voting falls within the purview of two distinct authorities: local sheriffs (who oversee and operate jails) and election officials (who bear responsibility for implementing voting procedures). A lack of cooperation (or downright obstruction) on the part of either of those actors can—and often does—make voting impossible for many jailed people who retain the right to cast a ballot.

Righting the wrong of jail-based voter disenfranchisement will not be a simple task, and the nature of the challenge will vary from state to state. However, advocates, policymakers, election officials, and sheriffs can all play a role in protecting the rights of eligible voters by combatting confusion about voting rules, eliminating unnecessary voting restrictions, and addressing the myriad logistical difficulties that prevent people in jail from casting ballots. Successful reforms will enable thousands of eligible voters to make their voices heard and will affirm that the voice of every voter matters.

Acknowledgements

Ginger and the Prison Policy Initiative thank the numerous experts who provided their insights during the preparation of this report, including Alec Ewald at the University of Vermont, Brenda Wright and Naila Awan at Demos, Leah Aden at NAACP LDF, Dana Paikowsky at the Campaign Legal Center, Dr. Brenda Williams at Family Unit, Inc, and Jen Dean at Chicago Votes. The author also thanks Peter Wagner, Emily Widra, Wanda Bertram, and Wendy Sawyer for their editorial guidance and technical support.

Rev. Dr. Yeary and the Rainbow PUSH Coalition thank the members of its boards of directors and the network of staff professionals, faith leaders, and community partners who stand in solidarity in the fight for the franchise. We especially thank Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, Sr. for the clarity of moral voice, conscience, and vision in advancing the cause of equal access to the ballot box.

About the authors

Ginger Jackson-Gleich is Policy Counsel at the Prison Policy Initiative, where she is primarily focused on advancing the Initiative’s campaign to end prison gerrymandering. Ginger has been involved in criminal justice reform for over 15 years and joins us in the interim period between clerkships. As a Harvard Law School student, Ginger interned at the Criminal Law Reform Project of the ACLU, the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, and the Alameda County Public Defender’s Office. She also represented low-income clients with the Harvard Defenders and the Criminal Justice Institute and served as an editor of the Harvard Law Review.

The Reverend S. Todd Yeary, J.D., Ph.D. is the Senior Vice-President and Chief of Global Policy of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, Inc., and serves as Senior Pastor of the Douglas Memorial Community Church in Baltimore. Dr. Yeary is also an adjunct professor in the College of Public Affairs at the University of Baltimore, teaching courses on Race, American Government, American Politics, and Community Building Strategies. Dr. Yeary holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Management from National-Louis University, a Master of Divinity Degree from Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, the Graduate Certificate in African Studies from Northwestern University, the Doctor of Philosophy Degree (Ph.D.) in the area of Religion in Society and Personality from Northwestern, and the Doctor of Law (JD) from the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit, non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. Alongside reports like this that help the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform, the organization leads the nation’s fight to keep the prison system from exerting undue influence on the political process (known as prison gerrymandering) and plays a leading role in protecting the families of incarcerated people from the predatory prison and jail telephone industry and the video visitation industry.

About the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, Inc.

The Rainbow PUSH Coalition (RPC) is a multi-racial, multi-issue, progressive, international membership organization fighting for social change. RPC was formed in December 1996 by Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, Sr. through the merging of two organizations he founded earlier, People United to Serve Humanity (PUSH, 1971) and the Rainbow Coalition (1984). The organization works to protect, defend, and gain civil rights by leveling the economic and educational playing fields, and to promote peace and justice around the world.

Footnotes

The majority of people in jail can vote, but we do not provide a more precise national estimate because the way jail data is reported at the national level makes it impossible to determine precisely how many people are eligible under each state’s different laws. It may be possible to calculate the number of eligible voters at an individual jail and/or at all jails in a particular state, but — at the time this piece was published — it was not possible to collect such information on a national basis. ↩

Although the precise number of people in jail may fluctuate from day to day, there is no reason to think that the number on Election Day would be meaningfully different from the daily average or that the composition of eligible/ineligible voters that are in jail on that day would be anomalous. Additionally, some people in jail cannot vote because of age or citizenship, but these individuals represent a small portion of the U.S. jail population; in 2018, there were approximately 3,400 juveniles held in adult jails, and in 2013, there were approximately 35,000 non-citizens held in jails (these are the last years for which data are available). ↩

However, if someone was either sentenced for a felony under the First Offender Act and their sentence has not been revoked, or they pled "nolo contendere" to a felony offense, they are eligible to vote. ↩

However, if someone is either on probation pursuant to the First Offender Act and their sentence has not been revoked, or they are on probation following a plea of "nolo contendere," they are eligible to vote. ↩

In August 2020, Governor Kim Reynolds restored voting rights for people with felony convictions (excluding homicides) via executive order, so people with past non-homicide felony convictions are no longer permanently disenfranchised. Presumably, until the law changes, people with new convictions may be permanently disenfranchised. ↩

Oregon does not disenfranchise all people serving sentences for misdemeanor convictions; it only disenfranchises people “serving a term of imprisonment in any federal correctional institution.” See Or. Rev. Stat. 137.281(5). ↩

In July 2020, the D.C. Council enacted legislation authorizing voting by people incarcerated on felony convictions. ↩

The most incisive discussion of the impact of sheriffs and election officials misunderstanding the law is the ACLU and Brennan Center’s 2008 report, De Facto Disenfranchisement. Readers should note, however, that one of the key examples discussed in that report — Kentucky — appears to be outdated, as our research indicates that Kentucky disenfranchises people incarcerated for misdemeanor convictions. ↩

For example, in California “new voters may have to show a form of identification or proof of residency the first time they vote, if a driver license or SSN was not provided when registering.” (See step 2 of this online voter registration tool.) ↩

Those states are: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia. For more info, see this report from the National Conference of State Legislatures. ↩

The National Voting Registration Act (1993) requires states covered by the Act to offer voter registration opportunities at motor vehicle agencies and also permits states to designate additional government agencies as places that offer voter registration services. ↩

In addition to the 19 states (and D.C.) that currently permit same-day registration on Election Day, New Mexico will begin to allow Election Day registration in 2021, and North Carolina currently permits same-day registration during early voting but not on Election Day. ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.