What is civil commitment? Recent report raises visibility of this shadowy form of incarceration

Shadowy “civil commitment” facilities actually foster the traumatic and violent conditions that they are supposed to prevent.

by Emma Ruth, May 18, 2023

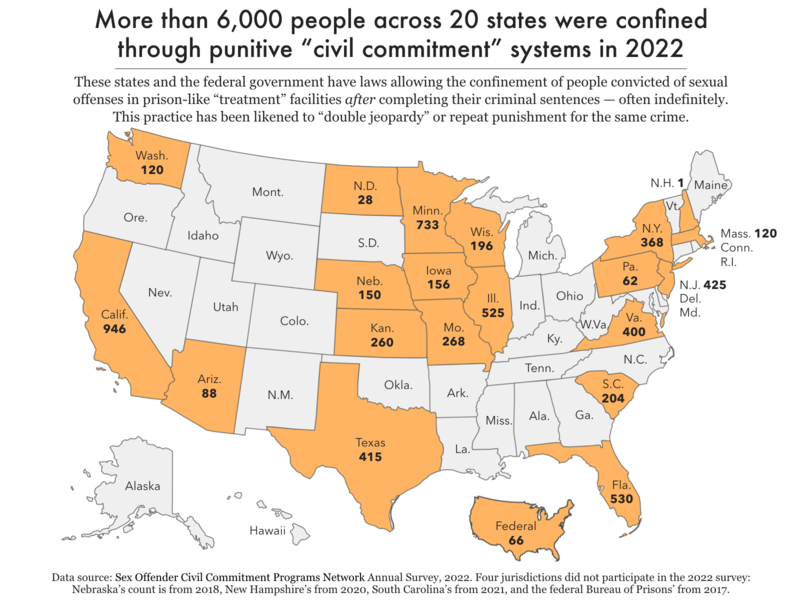

As if serving a prison sentence wasn’t punishment enough, 20 states and the federal Bureau of Prisons detain over 6,000 people, mostly men,1 who have been convicted of sex offenses in prison-like “civil commitment”2 facilities beyond the terms of their criminal sentence. Around the turn of the millennium, 20 states,3 Washington D.C., and the federal government passed “Sexually Violent Persons”4 legislation that created a new way for these jurisdictions to keep people locked up — even indefinitely — who have already served a criminal sentence for a “sex offense.” In some states, people are transferred directly from prison to a civil commitment facility at the end of their sentence. In Texas, formerly incarcerated people who had already come home from prison were rounded up in the middle of the night and relocated to civil commitment facilities without prior notice. This practice, though seldom reported on, made some news in 2017 when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a case from Minnesota after a federal judge deemed the practice unconstitutional. The Prison Policy Initiative has included civil commitment in our Whole Pie reports on U.S. systems of confinement, but here we offer a deeper dive, including recently-published data from a survey of individuals confined in an Illinois facility under these laws.

Two critiques of “civil commitment”

Some advocates call civil commitment facilities “shadow prisons,”5 in part because of how little news coverage they receive and how murky their practices are. In Illinois, for example, the Department of Corrections (DOC) facilities are overseen by the John Howard Association, an independent prison watchdog organization. But Rushville Treatment and Detention Facility, a civil commitment center that opened after Illinois enacted its own Sexually Violent Persons Commitment Act in 1998, is not subject to the same kind of oversight because it is housed under the Department of Human Services and is not technically classified as a prison.6 This is true in many states that have “Sexually Violent Persons” laws on their books, and consequently, horrific medical neglect and abuse proliferate in these shadowy facilities. For instance, a New Jersey civil commitment facility was one of the deadliest facilities at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similarly, Rushville is not held to the same reporting requirements as DOC facilities, so gathering data about people’s movement in and out of the facility is only possible by filing an open records request. Reportedly, the Bureau of Justice Statistics will take steps to begin collecting data about indefinite post-sentence ‘civil’ confinements in June of 2023. Until that happens, it’s only possible to get aggregated counts of how many people are civilly committed — nothing like the individual-level information prison systems are expected to provide in the service of transparency and accountability. This is true across the U.S., as civil commitment facilities are housed under different agencies from state to state, which makes it exceedingly difficult to measure the full scope of these systems on a national level. As a result, estimates about how many people are currently civilly committed vary from 5,000 to over 10,000 people.7 Increased accountability and oversight must be chief among efforts to address this broken turn-of-the-millennium policy trend.

A second critique of this system is reflected in another term advocates use to describe it: “pre-crime preventative detention.” Civil commitment (unlike other involuntary commitment practices, such as for the treatment of serious mental illness) can be seen as “double jeopardy” repeat punishment for an initial crime,8 or preventative detention for a theoretical future crime that has not occurred. Advocates rightly critique the fact that one of the primary justifications for civil commitment is the predicted risk that detained individuals will “re-offend,” even though people who have been convicted of sex offenses are less likely to be re-arrested than other people reentering society after incarceration.

Regardless, in many states, people who have been convicted of sex offenses are transferred from DOC facilities to civil commitment facilities at the end of their sentence and held pretrial, then re-sentenced by the civil courts. The length of these sentences is often indeterminate, as release depends on progress through mandated “treatment.” But neither “risk assessment” nor “progress through treatment” are objective measures. In fact, advocates and people who have experienced these systems argue that risk assessment tools are used to rationalize the indefinite confinement of identity-specific groups, and that assessing progress through treatment is a highly subjective process determined by a rotating cast of “therapeutic” staff.

New data: A survey of individuals held in a “civil commitment” facility

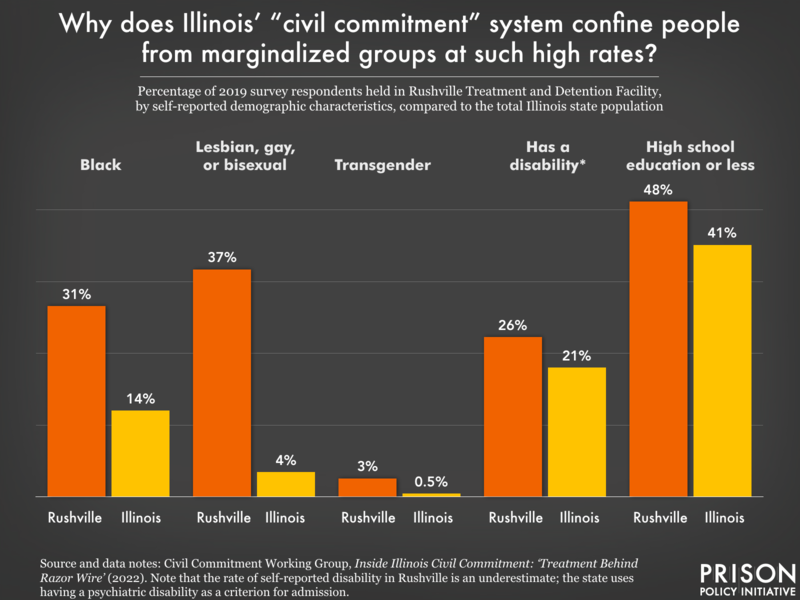

A recent report from Illinois (which I co-authored) goes beyond the numbers and reports that for many, civil commitment seems like a life sentence. This 2022 report, based on a 2019 study of residents at Rushville Treatment and Detention Facility (one of Illinois’ two civil commitment facilities), exposed demographic disparities, discrimination and abuses inside, and flaws with the broader framework of civil commitment. Like the broader carceral system, civil commitment disproportionately impacts Black and Brown people. In particular, the Illinois report noted an overrepresentation of Black, Indigenous, and multiracial people at Rushville. This is in line with the findings of the Williams Institute’s 2020 report, which found that, on average, Black people were detained in civil commitment facilities at twice the rate of white people in the states studied.

Biased admission criteria lead to disproportionate consequences for select groups

Further, the overrepresentation of LGBTQ+ and disabled people in these facilities reflects obvious biases that are “baked into” the civil commitment decision-making process. Many states use risk assessment evaluations to assess whether or not one should be civilly committed. These actuarial tools use outcome data from previously incarcerated people and conclude that, because past studies found groups with specific characteristics more likely to re-offend, individuals that match those criteria must be continually confined. Risk assessment tools are generally problematic and frequently make incorrect predictions. Chicago attorney Daniel Coyne says that in sex offense cases, risk assessment tools are 58% accurate, or “not much better than a coin toss.”

Illinois and many other states use the Static-99/99R, which predicts individuals’ risk using data about groups that come from overwhelmingly unpublished studies. This risk assessment tool is notably homophobic, as it assigns a point (and thus, a higher risk value) to those who have a “same-sex victim.”9 The Williams Institute writes:

In addition to normalizing violence against women, this a priori assigns gay, bisexual, and MSM [men who have sex with men], who are more likely to have a male victim, a higher score, marking them as more dangerous than men who have female victims regardless of any other characteristics of the offense.

The evaluation also considers those who have never lived with a romantic partner to be at higher risk of reoffending, which means that LGBTQ+ people who may not be able to safely live with a partner in a homophobic area and young people who may not have had the opportunity to live with a partner yet would receive higher scores. Accordingly, representation of LGBTQ+ people in Rushville was drastically higher than in the general public:

Criteria for detention usually include diagnosis with a “mental abnormality,” in particular, a personality disorder or a “paraphilic” disorder that indicates “atypical sexual interests.” “Paraphilic” is a problematic category that relies heavily on scrutinizing and pathologizing human sexuality.10 Further, the act of civilly committing people to a “treatment” facility implies that there is a mental health issue or “nonnormative” sexual behavior to be treated and/or cured. This is especially alarming given that the American Psychiatric Association completely disavows the practice, saying, “Sexual predator commitment laws represent a serious assault on the integrity of psychiatry.”11

Since having a “mental abnormality” is a criterion for admission, measuring the overrepresentation of disabled people in these facilities is challenging. By the logic of civil commitment, 100% of people inside have a psychiatric disability. In the Illinois report, 26% of Rushville respondents self-identified as having a disability, compared with 21% of the Illinois population. Low levels of educational attainment (i.e., having a high school degree or less) were also very high, at 48%. Anecdotally, survey respondents reported that many of their peers inside could not complete the survey because they were illiterate or had cognitive impairments that prevented them from reading and filling out a paper questionnaire, so disabled respondents’ voices are likely underrepresented.

Indefinite and punitive detention with no evidence of efficacy

Agencies that control civil commitment often insist that civil commitment is treatment, not prison. Texas Civil Commitment Center staff even went so far as to instruct detainees “to call their living quarters ‘rooms,’ not prison cells.” But advocates question whether or not civil commitment can be considered therapeutic. Can forced confinement inside facilities with high rates of violence, controlled by staff who use the same punitive measures that are common inside prisons, ever be healing?

Two-thirds of respondents inside Rushville in Illinois report that they have been sent to solitary confinement, a (potentially permanently) psychologically damaging practice. Rushville, like other civil commitment facilities across the U.S., also uses archaic treatment and evaluation technologies, including the penile plethysmograph, a “device [that] is attached to the individual’s penis while they are shown sexually suggestive content. The device measures blood flow to the area, which is considered an indicator of arousal.” Rushville detainees are subjected to chemical castration, or hormone injections that inhibit erection and have been linked to long-term health impacts. Further, their progress through treatment is measured using a variety of highly questionable evaluation tools, including polygraph lie detector test results which have been inadmissible in Illinois courts since 1981. The technologies that these facilities rely on look a lot more like medieval torture devices than the supposed “therapeutic tools” that they claim to utilize.

Even if we buy into the myth that civil commitment facilities provide the treatment they claim to offer, there is minimal evidence that this supposed treatment works, and moving through treatment tiers is difficult, if not impossible. Even staff inside report that they receive pushback when trying to advance people toward release. One review from a past employee of Rushville’s contracted mental health care service, Liberty Healthcare Corporation, reported, “The hardest part of the job is fighting for residents who should be on conditional release and dealing with the outcome when refusing to act in unethical ways.” Progress through treatment is dependent on a regularly fluctuating staff, often made up of graduate students who are finishing their residencies and then moving on to another facility. Residents inside report being demoted to earlier tiers of treatment by new residents who disagreed with previous staff members’ assertions.

With little transparency about or consistent standards regarding how to progress through treatment, many people inside say that civil commitment feels like a de facto life sentence. At Rushville, the average length of detention was 9.5 years and counting. According to a 2020 FOIA response from the Illinois Department of Human Services, more than twice as many people had died inside than had ever been released. Similar circumstances have been reported from Texas, where only five men were released in the facility’s first two and a half years of operation, four of whom were sent to medical facilities where they died shortly thereafter. A 2020 article about Rushville included the following findings:

Slightly more than half of the total population [has] been held for 10 years or more. Fifty-one people in Rushville have been held in civil commitment for 20 years or more, and 12 have been in civil commitment for 22 or more years, meaning they’ve been in civil commitment since the statute was implemented in 1998.

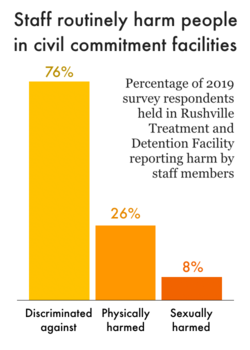

People inside reinforce these findings. One Illinois survey respondent reported, “This is a life sentence after the completion of a criminal sentence. We are treated worse [than] prisoners. This is a sentence of death by incarceration. Not a revolving door program.” Indefinite sentences that are contingent on progress through treatment that feels unhelpful and opaque contribute to distress inside. This distress can result in violence and a hateful culture, between detainees and from staff to detainees. Three-quarters of detainees report being discriminated against by staff, and one-quarter report being physically harmed by staff. 8% of detainees said they were sexually harmed by staff. Anecdotally, respondents shared a number of stories about experiencing physical or sexual harm from other residents. Though civil commitment facilities are tasked with “treating” sexual violence, they actually create physical environments that foster sexual, physical, and emotional violence.

Conclusions

Civil commitment facilities are not only legally and ethically dubious, they also fail to deliver on the very objectives that justified their creation. Even still, the trend toward preventative and “therapeutic” forms of detention that are fueled by biased and error-filled algorithms and risk assessment tools is growing. As one reporter from Texas notes:

Critics of private prisons see in the Texas Civil Commitment Center the disturbing new evolution of an industry. As state and federal inmate populations have leveled off, private prison spinoffs and acquisitions in recent years have led to what watchdogs call a growing “treatment industrial complex,” a move by for-profit prison contractors to take over publicly funded facilities that lie somewhere at the intersection of incarceration and therapy.

In an era where lawmakers frequently champion “evidence-based” punishment, the public must remain vigilant in questioning whether these practices actually accomplish their supposed goals. Do they reduce the mass incarceration of hyper-policed communities? Do they minimize the ongoing harms of the criminal legal system? Do they reduce the number of people entering prisons or increase the number of people exiting them? In the case of civil commitment, the answer to all of these questions is no.

Though under-resourced, the movement to address harmful civil commitment policies is longstanding. A variety of advocates12 are leading campaigns to address ineffective sex offense policies across the U.S. (including the sex offender registry system). Other organizations support ongoing litigation campaigns like the one that was considered by the U.S. Supreme Court in Minnesota. Advocates inside and outside agree that civil commitment facilities fail to deliver meaningful safety and healing.

It’s time for policymakers to close these facilities that leverage pseudoscience to keep people under state control. Instead, we must invest in initiatives that actually prevent child abuse and sexual violence, including measures advancing economic justice, accessible non-carceral mental healthcare, comprehensive sex education, and consensual, community-based restorative and transformative justice initiatives.

Footnotes

-

This data was provided by the Sex Offender Civil Commitment Program Network. ↩

-

We use the term “civil commitment” throughout because it has widespread name recognition, and because it accurately characterizes the civil legal system’s commitment of individuals to various facilities, but as we will discuss further, advocates often use more descriptive terms such as “shadow prisons” and “pre-crime preventative detention.” ↩

-

These states include Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. ↩

-

We reference these laws by name so that they are easier for readers who want to look up the statute to find, but do not endorse using this language to refer to people. ↩

-

For more information about the movement to change vocabulary around civil commitment, please see: https://ajustfuture.org/communications/ and https://ajustfuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/promoting-language.pdf ↩

-

Illinois also has a second civil commitment center within Big Muddy River Correctional Center. This program was created by the Sexually Dangerous Persons Act and it is run by the Illinois Department of Corrections. ↩

-

The Sex Offender Civil Commitment Program Network requests aggregate numbers from each state regularly — and these annual survey counts are what we use in our Whole Pie reports — but some advocates believe this is an underestimation because how one defines who is civilly committed varies between reporting agencies. For example, should those on “conditional release,” who are not confined but still subjected to stipulations of their state’s Sexually Violent Persons Act, be considered free? ↩

-

Defenders of civil commitment practices argue that civil commitment does not violate the Double Jeopardy Clause because the civil commitment proceedings are not re-litigating the initial criminal case, but using the criminal case as evidence in a subsequent civil case. ↩

-

For further critiques of risk assessment, the logic behind it, the inherent racism to its process, and its inaccuracies, see: https://www.aclu.org/news/privacy-technology/eight-problems-police-threat-scores; https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/prison-reform-risk-assessment/; https://jaapl.org/content/38/3/400.long ↩

-

From the Williams Institute report: “Critics have also noted the potential misuse of paraphilic disorders, a group of psychiatric diagnoses related to ‘atypical sexual interest.’ This category is extremely broad and includes pedophilic disorder as well as consensual sexual ‘kinky’ behaviors such as sexual masochism and sadism. The critique is that such diagnoses can be used [as] justification for civil commitment for a wide range of offenders. Paraphilic disorders diagnoses are so broad that they could be used to characterize as mentally ill many practitioners of kink, bondage, sadomasochism, or any sexual practice perceived to be deviant. This may have important implications for gay and bisexual men and [men who have sex with men], whose sexual cultures may be viewed as kinky or otherwise nonnormative due to stigma and prejudice” (pages 2-3). ↩

-

American Psychiatric Association, Dangerous Sex Offenders: a Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association (1999) ↩

-

These groups include (but aren’t limited to) the Inside Illinois Civil Commitment project, Just Future Project, the National Association for Rational Sexual Offense Laws, Illinois Voices, The Chicago 400 Alliance, Women Against the Registry, and CURE-SORT. ↩