Unhoused and under arrest: How Atlanta polices poverty

New research from the Atlanta Community Support Project finds 1 in 8 city jail bookings involve a person experiencing homelessness

by Luci Harrell and Brian Nam-Sonenstein, June 8, 2023

Poor people in the United States are a primary target for policing, especially those forced to live on the streets. But just how many people who are unhoused are caught up in the thousands of arrests made in cities each year? How many are criminalized for behaviors that stem directly from their extreme poverty? We combed through years of data from a variety of sources to answer these questions for the city of Atlanta.

Atlantans have long criticized their local governments’ reliance on policing over constructive community investments such as safe and affordable housing, medical and mental health care, food, employment, access to quality education, and accessible transportation. People who lack housing in Atlanta are punished for minor offenses that criminalize their survival. Missed court dates generate warrants for rearrest, and criminal records built through aggressive policing erect barriers to housing and employment, which in turn produce barriers to obtaining health care. The ensuing dynamic destabilizes access to what few community services are available. In the end, people who are unhoused are sucked into a gyre of poverty, arrest, and incarceration.

With the goal of informing interventions that will make such policing obsolete through support-oriented responses, the Atlanta Community Support Project (ACSP) set out to explore the scale and nature of policing for those battling homelessness at the city level. The following research represents the first stage of this project, in which we examined two years’ worth of Atlanta Department of Corrections’ daily jail logs to estimate just how disproportionately Atlanta’s unhoused residents are policed, especially for the “low-level,” quality-of-life violations that the Atlanta City Detention Center (ACDC) processes. Then, we matched local court records to a dataset of about 3,000 of these residents to better understand their interactions with the criminal legal system and the kind of access to support resources afforded to them. Using this dataset, we see that Atlanta’s unhoused population is among the most arrested in the city. For details about this study’s data sources, see the Methodology.

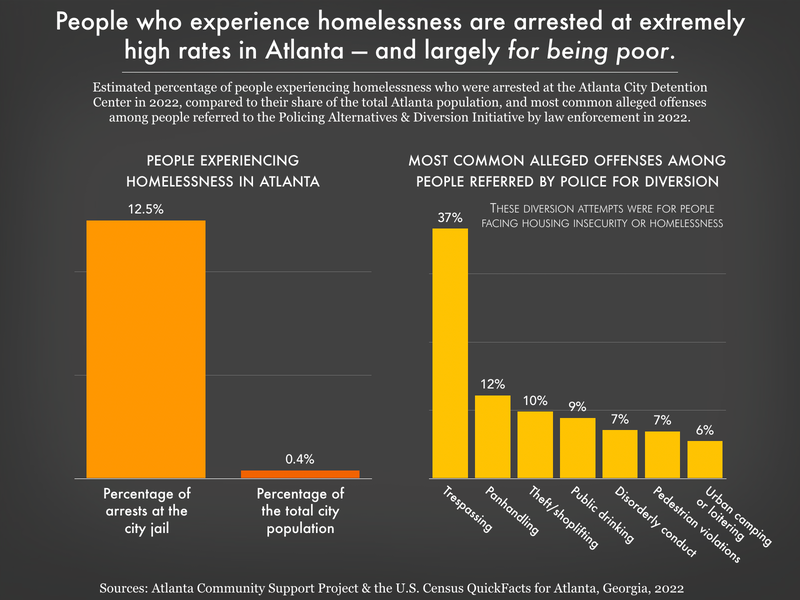

Most strikingly, we find that 1 in 8 Atlanta city jail bookings in 2022 — or 12.5% — were of people who were experiencing homelessness.1 That’s more than 30 times greater than the proportion of the city’s full population that is experiencing homelessness. The Atlanta Community Support Project’s analysis of our dataset of people who had recently faced homelessness also found that:

- Policing further indebts the unhoused: 41% had outstanding fines and fees in Fulton County and/or Atlanta Municipal Court averaging $536.

- Most people who are unhoused struggle to attend court hearings, often because they don’t even know about them: 86% of those who had been incarcerated at the city jail also had bench warrants for failure to appear in court.

- People living unhoused and known to law enforcement were disproportionately Black, women, and/or transgender:

- 78% were Black

- 30% of those who had been recently incarcerated were women

- Of those in the dataset who were able to self-report race and gender identity, 5.7% self-identified as trans, and 89% of trans individuals also identified as Black.2

- Service providers don’t have the funding to reach enough people: Only 28% had received wraparound assistance as an alternative to incarceration through a local organization known as the Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative (PAD).

Who is most impacted by poverty policing?

As is the case with most other cities, the vast majority of arrests in Atlanta are for minor offenses committed by people with the fewest resources. The Atlanta Police Department (APD) reported arresting nearly 19,000 people in 2021, with approximately 3,000 people detained in the overcrowded Fulton County Jail on any given day. More than half of APD arrests between 2013 and 2021 were for “low-level offenses” most often classified as misdemeanors and exemplifying quality-of-life issues such as mental illness, substance use, homelessness, and/or sex work.

Meanwhile, nearly 1 in 5 Atlantans live in poverty. Last year, 18.5% of Atlanta residents were living in poverty and 2.2% of those living in poverty were experiencing homelessness.3 While gentrification created a steady rise in the city’s median household income, the poverty rate rose steadily alongside it, as did the housing crisis.

While we are considering the extent of the poverty crisis in Atlanta, it’s important to note that available data on homelessness does not capture the extent to which people are dealing with the broader issue of housing insecurity. These data do not account for people living in temporary housing, on the verge of losing their housing, or those living in inadequate conditions.4 That means the real level of precarity is far worse than reflected in available data on homelessness.

Nonetheless, the data show that Atlanta’s policing of homelessness is extensive and deeply concerning. As we mentioned, nearly 13% of all city jail bookings in 2022 were of people who reported or presented as experiencing homelessness even though the homeless population accounts for less than half of a percent (0.4%) of the total citywide population.

We also found that homelessness in Atlanta intersects with age, race, and gender in such a way that concentrates the impact of poverty policing among people who are already experiencing severe neglect and marginalization.

Older people are targeted as their homelessness rate rises

People over the age of 50 composed the largest age group in the Atlanta Community Support Project (ACSP) dataset of people who had recently faced homelessness. Ten percent of this group are or will be 62 years old or older in 2023. This is noteworthy because older adults are the fastest growing group of people experiencing homelessness nationwide.

Criminalizing the homeless elderly population produces significant collateral consequences, compounding health issues for people who are already at higher risk of illness, injury, and disease. Policing the elderly is also deeply disruptive to their receipt of services that can have the biggest impact on their survival, such as Social Security and Medicare benefits.

Black people are overrepresented among those living unhoused, arrested, and jailed in Atlanta

Black people are impoverished and policed at the highest rates throughout America, and that reality was apparent in our research on the city of Atlanta. Among those represented in the ACSP dataset, 78% were Black, compared to 48% of the total city population. The racial disparities are even more extreme among people arrested and jailed: Black people account for 90% of all arrests made by the Atlanta Police Department and more than 90% of the Fulton County Jail population.

Even when taking into account systemic failures to accurately record the ethnicity or race of those who are policed — especially individuals who report two or more races — Black people are disproportionately represented at every step of the criminal legal system.

On the streets, women and trans people are targeted for arrest

Women compose roughly 15% of jail populations nationwide,5 but in Atlanta, they account for nearly a third of those who are both criminalized and homeless: 30% of people in the ACSP dataset who had experienced both homelessness and local incarceration in the past two years identified as women.

As is true with data collection on race and ethnicity, gender identification in the ACSP dataset is imprecise because law enforcement routinely misgenders people. However, 512 people in the dataset self-reported their demographic information with the Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative; of these, 29 (5.7%) identified as transgender. These self-reported data also give us a partial view of the intersections of race and gender among people targeted for poverty policing in Atlanta: Of the 29 people in the dataset who self-identified as trans, 89% also self-identified as Black.

Punishing survival: Policing quality-of-life issues

Although a complete analysis of charge data for people who were unhoused when arrested and processed at the Atlanta City Detention Center (ACDC) was out of scope for this study, 2022 data from the Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative (PAD) give us a sense of how this population is routinely criminalized for minor offenses, many of which amount to basic survival, having nowhere to go, and asking others for help.8 In fact, 99.6% of all law enforcement assisted diversions to PAD involved offenses that would have been considered misdemeanors if charged. In 2022, referrals made by law enforcement to PAD for diversion9 were most frequently related to allegations of:

- Trespassing (37%)

- Panhandling or soliciting (12%)

- Theft or shoplifting (10%)

- Public drinking (9%)

- Disorderly conduct (7%)

- Pedestrian violations (7%)

- Urban camping or loitering (6%)

- Indecency (5%)

Despite the high level of need, the frequency of police contact in response to these minor violations, and the efforts of the city to divert more people away from arrest, our analysis of ACDC bookings shows that poverty arrests are still all too common. Only 28% of people in the ACSP dataset — all of whom have likely been eligible for diversion — have actually received assistance from PAD. Greater interventions are needed to meet the level of need. PAD’s monthly report for April 2023 shows immense gaps between the number of diversion-eligible arrests and pre-arrest diversions. For example, APD Zone 2 — which includes some of the city’s wealthiest and whitest neighborhoods — saw 105 arrests that were eligible for diversion that month, but only one pre-arrest diversion took place. Trespassing and panhandling made up the majority of charges at the time of diversion, and housing and food were the services most often provided.

It’s worth noting that, nationally, public order offenses account for over half of all rearrests, which is to say that people are repeatedly arrested for a broad category of offenses that includes driving while intoxicated and disorderly conduct. Relatedly, misdemeanors were the most serious charge for nearly 40% of all bookings at Fulton County Jail in 2022.

The Superior Court of Fulton County has a “Familiar Faces” initiative aimed at identifying people who “frequently cycle through jails, homeless shelters, emergency departments and other crisis services.” According to PAD, people in the initiative are defined as those who have been “booked three or more times within 24 months for non-violent offenses, who do not have violent offenses in their booking history in Fulton County, and who have a mental health screen score of 5 or greater.” PAD notes that the jail had designated nearly 4,000 people as “Familiar Faces,” amounting to just over 9,000 bookings between 2020 and 2022. The average length of incarceration was 20 weeks.

It’s easy to see how a rise in stigmatizing campaigns led by city and county officials that center “repeat offenders” almost exclusively targets Black Atlantans living in poverty.10 In its 2022 Annual Report, the Atlanta Police Foundation’s “Repeat Offender Commission” disclosed that, of the 1,500+ people it profiled and targeted in 2022, 93% were African American.

Reproducing poverty through criminalization

Making it harder to house people

Arrest and incarceration present significant barriers to housing. Even a recent White House plan to reduce homelessness 25% by 2025 recognized the criminalization of homelessness as a key contributor to the 3% rise in people experiencing unsheltered homelessness across the country.

Nationally, people who have been to prison one time experience homelessness at a rate nearly 7 times higher than the general public, as the Prison Policy Initiative found in a previous study. People incarcerated more than once have rates that are 13 times higher.

Part of the problem is that federal guidelines give public housing agencies — which have the potential to be a much more substantial bulwark against housing insecurity — the discretion to discriminate against people with criminal convictions. While most renters find a place to live in less than a month, the process can take years for those relying on the Housing Choice Voucher program.

Even in Atlanta, where an anti-discrimination ordinance passed last year to protect people directly impacted by the criminal legal system, background checks are still a routine part of the public housing application process. And if someone is arrested during the lengthy and complicated application process, they may have to start all over again so that the new arrest can be scrutinized.

For those living on the brink of homelessness, pandemic-related housing protections like eviction bans and rental assistance have all expired as of July 2022. Though most states require a waiting period before a landlord can move forward with an eviction, Georgia law allows landlords to proceed “immediately” after a tenant has been given notice to vacate. That’s a sharp blow in a state where the minimum wage is one-third of the roughly $21 an hour wage necessary to afford a 2-bedroom apartment.

Struggling to attend court

Poverty makes it exceedingly difficult to make court appointments, but homelessness makes it even harder. Of those in our ACSP dataset who had ever been incarcerated at the Atlanta City Detention Center, 86% also had at least one warrant on record for failing to appear in court.

If someone accused of a crime misses court, a judge can issue a “bench warrant” for their arrest. In Atlanta Municipal Court, a “failure to appear” entry is automatically accompanied by a bench warrant and a $50 fine (which may be waived at a later time at a judge’s discretion). While there is currently no firm national estimate of the number of active bench warrants, it is widely understood that they make up a significant portion of overall warrant activity.

Bench warrants are a blunt tool that are often unnecessary. Most people who miss court are charged with minor crimes and are not trying to avoid the law; more often, they forget, are confused by the court process, cannot read the handwritten citation, or have a schedule conflict. To complicate matters further, people who are unhoused cannot afford to miss work and often cannot obtain reliable transportation, childcare, and keep consistent cell phone service which would allow them basic communication and access to online resources.

Atlanta, like most cities, chooses to notify people of their court dates via snail mail, which makes it virtually impossible for an unhoused person to reliably comply. Once a warrant is issued for failure to appear, those accused frequently end up living as “low-level fugitives,” quitting their jobs, becoming transient, and/or avoiding public life (including hospitals) due to the risk of police interactions that could further upend their lives.

Existing oppressive practices do not seem to be enough for local lawmakers. A new law in Georgia (SB44, Section 3), passed in 2023, requires cash bail for anyone who has had a failure to appear bench warrant in the past five years. The year before, an in-depth review of case files for 250 people found that 30% were at Fulton County Jail because they couldn’t pay a bond of $15,000 or less. One individual spent nearly 500 days in jail because he couldn’t afford his freedom. As poverty obstructs a person’s ability to make court appointments, unaffordable cash bail essentially ensures that those who are unhoused will be jailed.

Nickeled and dimed

It’s expensive to be poor. Poverty policing assigns fines and fees to the people who can least afford them. Our Atlanta dataset bears this out, as we found 41% of people have outstanding criminal legal debts in Fulton County and/or Atlanta Municipal Court, averaging $536 each.11 This does not include cash bail amounts levied against just the individuals in our dataset by Fulton County State and Superior Courts, which amount to roughly $20 million in total.12

Conclusion

Policing homelessness in Atlanta is essential to maintaining a precarious and patently unjust status quo. Not only is it required to manage the displacement wrought by the city’s rapid gentrification by real estate developers and local leaders’ refusal to enact rent control legislation, but it justifies ever-greater investments in law enforcement and carceral control.

Similar dynamics are at play in cities across the U.S., which makes undertakings like ours in Atlanta a crucial example. Unearthing just how much policing focuses on homelessness, and what that policing looks like, can inform budgetary reorganizations and community interventions that will make poverty policing obsolete.

Atlanta’s residents are currently engaged in a pitched battle against Cop City, which entails the deforestation of the city’s oldest Native lands to build the nation’s largest militarized police training facility, because it is an aggressive escalation in this harmful model — but importantly, one that is not preordained.

Though successful campaigns to close and repurpose the Atlanta City Detention Center (ACDC) have backslid into plans to lease space to the Fulton County Jail, Atlantans remain fighting on all fronts for a different future. The city recently made people with criminal records a protected class, meaning that they cannot be denied housing and employment based on their records. Meanwhile, community interventions like PAD, for example, have drastically reduced rearrest rates among people in this population who are participating in their programs for 6 months or more.

Following through on task force recommendations for closing ACDC could generate an estimated 77% drop in bookings at ACDC by reducing the scope of the city’s “quasi-criminal” code, converting many offenses to civil infractions, and prioritizing diversion and other alternatives to arrest.

As for the ACSP, our next step is to use these findings to mobilize those of us most harshly affected by the criminalization of poverty, to create tools that bolster participatory defense and empower people to advocate for themselves in court, before discriminatory landlords and employers, and to voice concerns to elected representatives. We aim to demystify the legitimate fear associated with showing up to court and being involved in one’s own criminal legal process, so that people can have debilitating fines and fees waived and stale cases closed.

At the most basic level, the strongest pathways to ending homelessness in Atlanta run headlong into police encounters, which must be reduced.