Heat, floods, pests, disease, and death: What climate change means for people in prison

Without consistent access to relief or safer environments, incarcerated people are punished with deadly heat, increased biological threats, and flimsy emergency protocols. We explain new epidemiological evidence confirming that heat and death are linked in prisons nationwide, and explain why the climate-change-induced plight of people in prisons deserves swift action.

by Leah Wang, July 19, 2023

Heatwaves and extreme weather events are now commonplace. States across the South and Southwest are experiencing record high temperatures (during the day and at night, which is a big deal). Meanwhile, the Northeast has been drenched in more frequent, torrential rainfall and flash flooding. Prisons and jails nationwide aren’t insulated from these events, yet we rarely see how bad the conditions are for the millions of people locked within them.

Hopefully, readers have seen our prior work — or any of several other powerful essays — explaining the ways in which extreme heat, combined with a lack of air-conditioned spaces and cooling measures, is especially harmful to people behind bars. Some have described the experience as being trapped in heat-retaining “convection ovens.”1 We’ve also highlighted some of the environmentally disastrous ways prisons are sited and operated.

In this briefing, we present new findings from a nationwide, epidemiological study showing a strong relationship between extreme heat and deaths in prisons — especially in the Northeast. We also explain why extreme heat isn’t an isolated danger — it’s wrapped up in other hazards like pests and diseases guaranteed to make prison life miserable, if not fatal.

New research confirms what we already know: Extreme heat and deaths are linked in prisons nationwide

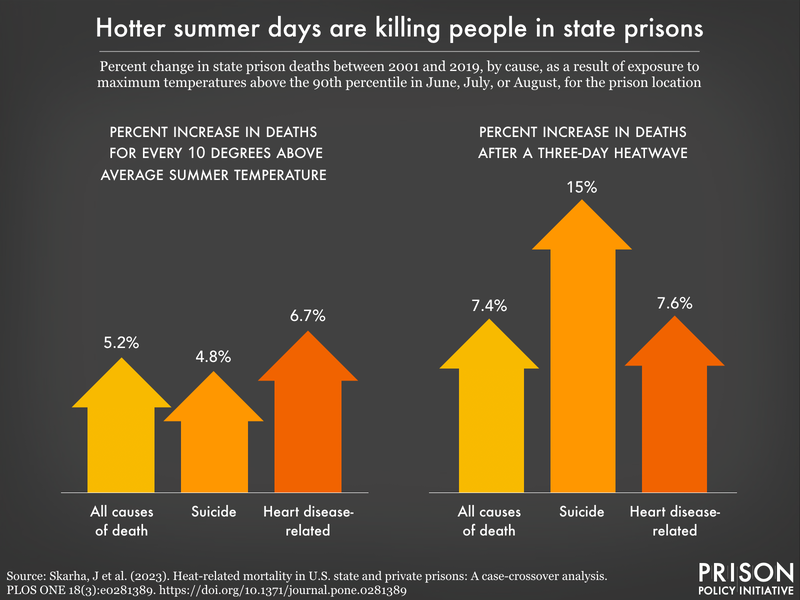

A group of researchers, led by epidemiologist Julianne Skarha, offer new evidence that the heat we’ve been experiencing is particularly deadly for incarcerated people across the U.S.2 Using two datasets — annual deaths in state prisons from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and hourly temperature data from the North American Land Data Assimilation System — the researchers looked at unusually high temperatures occurring in the summer months at the geographic location of prisons.3

Using established public health research methods, the study’s authors were able to look at exposure to a “risk” or an event — in this case, hotter-than-average days or multi-day heatwaves,4 and observe an acute outcome — deaths in state prisons (categorized as suicide, heart disease, or death from any cause). They examined deaths that occurred up to three days after each heat event.

As expected, unusual heat was associated with higher overall mortality. The researchers found for every 10 degree increase above the prison location’s mean summer temperature, nearly 5% of deaths (from all causes) occurring there could be attributed to the heat. Even the days following a hotter-than-average day were associated with deaths, although the risk of heat-related death declined, suggesting that mitigating heat right away is crucial.

Further, an extreme heat day (one that falls within the hottest 10% of days for a particular location) was associated with a 3.5% increase in deaths. These extremely hot days had a delayed effect on suicides, which increased by 23% over the three days that followed. As if prison environments weren’t already damaging enough to mental health, the oppressive heat and a prison’s failure to provide relief from it can drive someone into unbearable distress.

Two- and three-day heatwaves (defined as consecutive days of extreme heat) were even more dangerous, increasing deaths by 5.5% and 7.4%, respectively. There were similar trends with deaths from suicide and heart disease, but they were not statistically significant.

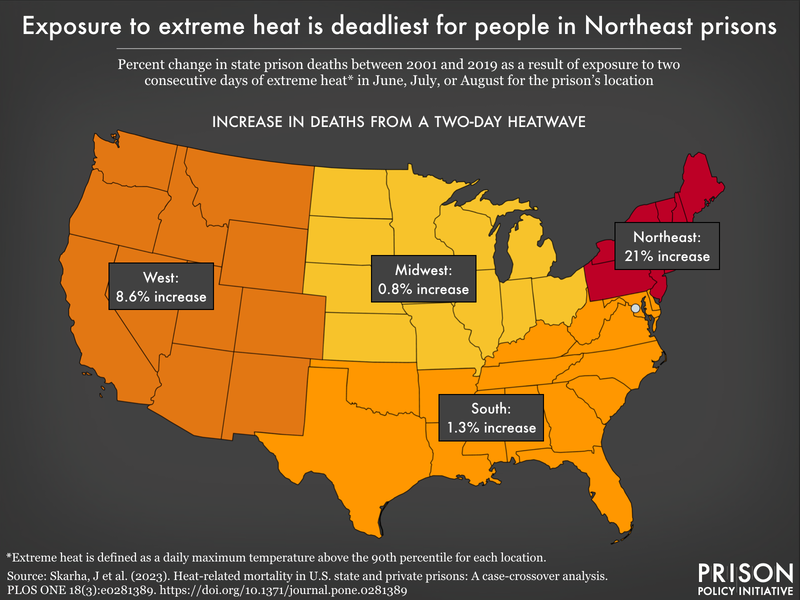

The study’s authors also found that the impact of heat on mortality was highest in the Northeast region, 5 which tracks with evidence suggesting heat-acclimated populations might fare better in a hotter world. So even though states like Texas are rightfully scorned for failing to provide livable environments for people in prisons,6 more temperate states (like those in New England) aren’t off the hook either.

The results, as terrible as they are, likely underestimate the deadly effect of heat in prisons without A/C, as air conditioning data were not available for this analysis. The researchers also noted that they didn’t have data on the type of housing individuals were held in before they died, such as a solitary confinement cell.7 Despite these limitations, Skarha et al. offer the first nationwide, peer-reviewed publication showing that prisons, which are deadly places already, are heating people to death.

Prisons fail to provide desperately needed relief from heat and other emergencies

As we mentioned in our 2019 investigation, air conditioning is not a universal feature of prison buildings in famously hot states, even though it is nearly ubiquitous in homes across the South.8 Short of prison A/C — which states will spend more money fighting through lawsuits than they would installing — incarcerated people are seldom provided other forms of temporary relief. A survey conducted in California prisons by the Ella Baker Center found that most respondents didn’t have access to more water or showers on particularly hot days. Meanwhile, 62% of respondents reported experiencing heat exhaustion and 41% reported heat cramps due to extreme heat and/or nearby wildfires. Two-thirds (67%) of respondents said they were worried or extremely worried about their physical safety in the case of extreme heat at their prison.

And even though judges in multiple states have ruled that subjecting incarcerated people to extreme temperatures is unconstitutional, they haven’t mandated any relief measures. Public opposition to providing “comfortable” carceral spaces has further compelled prison officials to do nothing about this life-or-death issue.

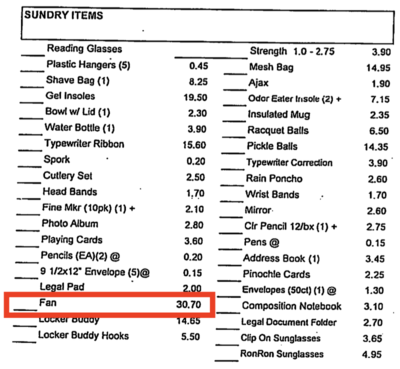

It would take more than a week’s worth of earnings at a federal prison in Texas for most people to afford this electric fan.

Even the mild relief of a fan or a towel can be hard to come by in prisons. These items might be available, though unaffordable, through a commissary: In one federal prison, where most people make less than $0.50 per hour, a fan costs $30.70. And in Oregon, where a heat wave brought 100-plus degree days in 2021, one prison offered special “cooling” towels for $18 — a nearly 100% markup.

Aside from placing the burden on incarcerated people to gather these threadbare comforts, prisons are largely unprepared to respond to facility-wide emergencies and disasters. There is no national mandate for correctional facilities to form emergency preparedness plans, to have evacuation drills, or to train staff on emergency protocols.9 The same Ella Baker Center survey found that the vast majority of incarcerated respondents did not know of any plan describing their prison’s emergency procedures for extreme heat (72% were not aware), extreme cold (88%), wildfires (88%), or flooding (92%).

Extreme weather is intertwined with other biological and social threats, leaving people in prisons highly vulnerable

As we and others have been saying for years, increasing heat is especially dangerous for people in prisons. But the heat itself is not the only issue. What other aspects of the prison environment will worsen as the climate changes?

Mosquito infestation

Mounting heat and humidity will lead to changes in pest populations nationwide, and incarcerated people will only fare as well as state mitigation strategies will allow. In Utah, for example, where a brand new prison recently opened near the wetlands of the Great Salt Lake, mosquito populations are thriving in ideal conditions. Despite great concern about this decidedly bad location, the mosquito problem at Utah State Prison has gotten so bad that prison officials have been scrambling for solutions.10

Utah prison officials’ ill-conceived responses include selling insect repellent in the prison commissary (instead of providing it for free) and training staff to use pesticides to kill mosquitoes, leading to unintended consequences for other parts of the sensitive ecosystem. Such consequences are also borne by the thousands of people who live and work in the area.11 Seeing as biological diversity is our best defense against climate change, it’s devastating to see how the new Utah prison is proceeding to destroy such an important, fragile place, while putting its incarcerated population at risk of mosquito-borne illness, flooding, and contaminated water.

Infectious diseases

As we detailed in our comprehensive report about the health of incarcerated people, and over three years of COVID-19 reporting, infectious diseases disproportionately impact those in prisons, where modern medicine and public health directives go ignored.

The number of infectious disease outbreaks (by growing populations of mosquitoes and ticks, for example) has risen along with average global temperatures. There is some emerging evidence, for example, that climate change is contributing to a rise in Valley Fever, a deadly fungal infection that has plagued people imprisoned in the Southwest for years. Based on decades of evidence, prisons and jails aren’t likely to be prepared for the increasing threats of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

Violence

As the weather warms, prisons will demonstrate the well-documented relationship between heat and violence. A July 2021 study found that unmitigated exposure to heat — even after accounting for dozens of other factors — increased violent events in Mississippi prisons. Aside from the physical harm of violence and the mental health damage caused by living in a violent place, the study’s authors predict that violence under “thermal stress” may perpetuate mass incarceration: People pushed to act violently in prison are more likely to have disciplinary infractions that delay their release, and the overall harsher prison conditions caused by heat may increase the odds of recidivism once released.12 Clearly, lawmakers should consider the immense social and financial benefits that a universal necessity like air conditioning could have in their state prisons.

Environmental emergencies are the norm in a climate-changed world. While we focused on heat-related dangers in this briefing, the kinds of failures we described are present in how prisons deal with other weather events as well: Floods, fires, hurricanes, cold snaps, and blizzards are all particularly threatening to the lives of incarcerated people. Deteriorating infrastructure and harmful policies around charging fees for medical care, privatizing care and commissary items, and failed emergency protocols are intensified by an increasingly volatile environment.

Even though incarcerated people regularly organize for their own survival needs, they face an especially daunting challenge building climate resilience. The deck that is stacked against them grows as our surroundings become more inhospitable. And the impacts of climate change on incarcerated populations will ripple out to surrounding communities, making this an issue we should all care about. Places of confinement and the people inside them must be part of any effort to reduce the harms of climate change. The status quo is nothing short of an overlooked crisis.

Footnotes

-

Many people in prison are especially susceptible to heat-related illness, as they’re more likely than the general population to have certain health conditions or take medications that make them especially vulnerable to the heat. ↩

-

This study follows one published in late 2022 (for which Skarha is also the lead author) focused on Texas prisons, which are notorious for sweltering conditions. The 2022 study leverages the fact that air conditioning is provided in some Texas prisons, but not all. Those researchers found that some deaths could be attributed to heat in those prisons without A/C, whereas no deaths could be attributed to heat in climate-controlled prisons. ↩

-

The researchers note they were not able to complete their analysis for Alaska and Hawaii due to a lack of temperature data. ↩

-

The study’s authors used the mean summer temperature at each location for their analysis, and determined extreme heat events using a maximum temperature greater than the 90th percentile for the respective location over 1, 2, or 3 consecutive days. Under this definition of extreme heat, the cutoff point for some prison locations was quite mild, so the authors chose to exclude prisons in locations where the

90th percentile was less than or equal to 77*F.

↩ -

The researchers defined the Northeast region as Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. ↩

-

On the other hand, since 1994, county jails in Texas are required to maintain internal temperatures between 65 and 85 degrees. ↩

-

However, the researchers did exclude deaths that occurred in 12 prison facilities across the U.S. that are specifically designated for medical treatment and operate similar to a hospital. ↩

-

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2020 Residential Energy Consumption Survey, 94% of homes in the South (referring to Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma plus Washington, D.C.) used air conditioning. ↩

-

According to Melissa Savilonis, who wrote a 2013 doctoral thesis on emergency planning in correctional facilities, prisons are entirely left out of emergency preparedness activities, even though the federal government “places emergency management at the forefront of government priorities.” The Stafford Act, which is the major federal law authorizing federal dollars for emergency disaster relief to state and local governments, and the Post Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act, which was intended to address the failure to adequately respond to communities impacted by Hurricane Katrina, are both silent on incarcerated populations and/or correctional facilities. The Stafford Act does mention pets as a vulnerable population, however. ↩

-

Overall, climate change is predicted to have a negative impact on biological diversity — in other words, many insects and other species will die off. But this doesn’t mean living blissfully free from bug bites: We’ll be losing insects that are critical to healthy, functioning ecosystems, as well as our global food supply. Yet some insect populations, like mosquitoes and ticks, are predicted to grow alongside changing conditions and decreasing populations of natural predators. ↩

-

Unfortunately, harmful chemical agents are overused and weaponized in the confined spaces of prisons and jails. Earlier this year, several people sued an ICE detention facility in Adelanto, Calif., claiming staff indiscriminately sprayed HDQ Neutral, a corrosive cleaning chemical, throughout the building. Ingesting the chemical led to rashes, respiratory issues, and headaches. And correctional officers regularly use chemicals like tear gas and pepper spray to incapacitate people, instead of using de-escalation techniques or trained mental health professionals.

At the same time, corrections officials are quick to divert attention away from these harmful activities and claim that incarcerated people are the ones misusing chemicals. In one case, a Florida sheriff claimed the people in his jail were using roach spray to get high. Claims like this are often overblown and weaponized to restrict services, programs, and privileges, given the reality that actual drugs are fairly easy to obtain while behind bars (through staff, often).

↩ -

Of course, violence in prisons during hot weather would only mirror increases in violence (and other behaviors considered crimes) outside of prisons. These increases will also fuel mass incarceration through more arrests, more jail admissions, and more people sentenced to prison. ↩

Prisons in the USA, as in many other countries, are run on the principle of less eligibility, modelled in the British workhouses of the 19th century.

“The government’s intention was to make the experience of being in a workhouse worse than the experiences of the poorest labourers outside of the workhouse. This policy was to become known as the principle of ‘less eligibility’. This was a punitive approach, borne out of a desire to deter idleness and curb spending relief on ‘able-bodied’ people.”*

One consequence is that prisons must be made to be more damaging to their inhabitants than the worst housing available to the poorest people in the society in which the prison is situated. The USA has appalling levels of deliberately-imposed poverty when compared to similar so-called developed societies, and one consequence of this situation is the chronic vulnerability of impoverished Americans to climate change and disease. Federal and state governments are committed to ensuring that all prisoners live worse lives than the poorest free person in the nation; if this were not the case, where is the punishment?

The corporate media (as here in the UK) reacts with venom and malice towards any suggestion that the lives of prisoners are too miserable. Their response is always the same: it’s no better for a lot of Americans (although why this is the case cannot be explained, it’s just the way of things), so why should the “vile scum” who have committed crimes have their conditions improved? Briefings such as this one by Leah Wang are unlikely to result in substantial enhancements to prison conditions. For that… you need socialism and a united working class.

https://navigator.health.org.uk/theme/workhouses-and-poor-law-amendment-act-1834