Not an alternative: The myths, harms, and expansion of pretrial electronic monitoring

The expansion of pretrial electronic monitoring across 70 counties threatens to undermine Illinois’ groundbreaking Pretrial Fairness Act, despite both the lack of evidence of EM's efficacy and its well-documented flaws and harms.

by Emmett Sanders, October 30, 2023

Illinois recently made history by becoming the first state in the nation to end money-based pretrial detention with the implementation of the Pretrial Fairness Act. In response, the Illinois Office of Statewide Pretrial Services announced the expansion of pretrial electronic monitoring (EM) to 70 of Illinois’ 102 counties, many of which did not have it before. While Pretrial Services touts this as something to be celebrated, the advocates who originally fought for the Pretrial Fairness Act and other scholars have pointed out that this massive expansion of state control undermines the spirit of bail reform.

The Pretrial Services agency’s statement reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of what research and evidence shows about electronic monitoring. As Michelle Alexander, legal scholar and author of The New Jim Crow, recently explained in an impassioned video, electronic monitoring is faulty technology that further embeds systemic injustices in communities of color, creates new avenues of harm, and does remarkably little to increase court compliance or public safety.

Electronic monitoring is not evidence-based

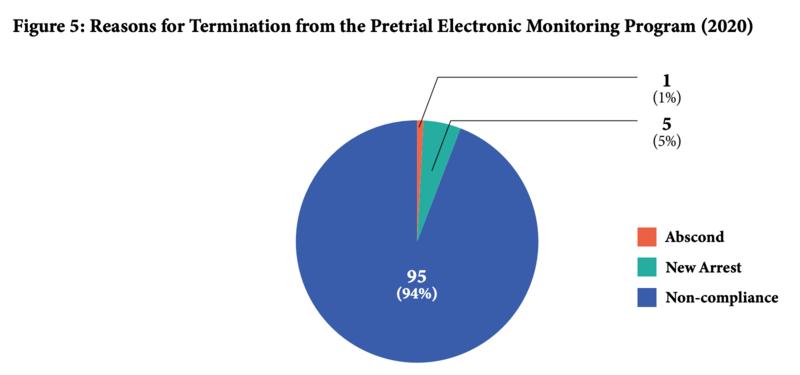

Stakeholders looking to innovate in pretrial policy often look for evidence-based practices—strategies with a documented ability to increase court compliance and positively impact public safety. While electronic monitoring proponents present the technology’s ability to do these things as a forgone conclusion, the reality is that few rigorous studies have been done to examine these claims. However, those that have, such as this new study conducted by nonprofit research group MDRC, find EM neither increased court appearances nor reduced new arrests. As this study notes, people on EM may have more new arrests than those not monitored, as the intense scrutiny of people on EM spotlights even minor infractions that might otherwise go unremarked. Researchers also note pretrial EM creates an entirely new path to incarceration via “technical violations,” which have nothing to do with criminality or public safety, but rather with the impacted person’s ability to navigate a multitude of ambiguous and often draconian conditions. In Los Angeles County between 2015 and 2021, 94% of people on EM who did not successfully complete EM were sent back to jail for technical violations rather than for a new arrest:

People may even be charged with felony escape for violating conditions or tampering with the device, and serve years in prison even after being found innocent of the charges that garnered them pretrial EM to begin with.

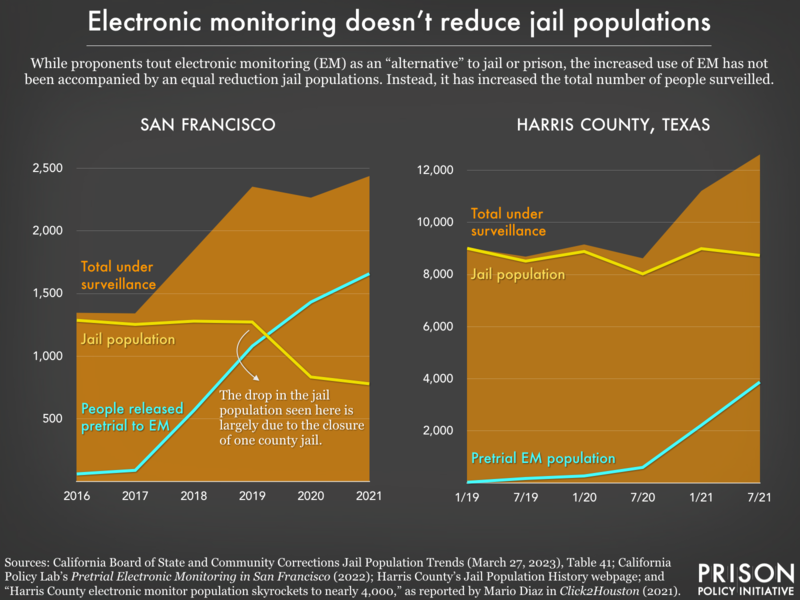

Electronic monitoring does not reduce jail populations

While EM programs are often depicted as replacing traditional brick-and-mortar incarceration, the reality is these programs are often used to augment and expand the reach of incarceration and may have little effect on the population of the jail itself. EM programs around the country have massively expanded, often in the wake of successful pretrial reform efforts. This has prompted advocates such as the No New SF Jails Coalition to include halting the expansion of EM in their decarceration demands, as they did when they finally closed the 402-bed jail at 850 Bryant in 2020. Nevertheless, San Francisco’s jail population was back up to 1,061 at last count, even though the number of people released on EM grew from 60 in 2016 to 1,659 by 2021. Similarly, the Harris County, Texas jail population of 9,533 reported for October 2023 is even higher than it was before the county’s EM usage exploded from 27 in 2019 to nearly 4,000 in 2021. Ultimately, jail populations in many jurisdictions have remained essentially the same or have even increased while EM usage has skyrocketed, significantly increasing the total number of people under surveillance:

Electronic monitoring uses faulty technology

Proponents of EM also downplay the reality that the technology itself is unreliable. Signal drift (the propensity of GPS to place people where they are not), interference from architecture, and data issues are widespread and persistent:1

- In May of 2017, Wisconsin’s Department of Corrections lost GPS signals for the 864 people electronically monitored roughly 57,000 times, translating to more than 2 false alarms per person per day.

- In 2021 researchers in Chicago discovered that of the tens of thousands of alarms received each month, roughly 80% are non-actionable.

- A 2021 article revealed a massive security breach with EM company Protocol which resulted in the private data of thousands under Chicago’s EM program being exposed online.

None of this prevents monitored people from being woken up in the middle of the night to be harassed, handcuffed, and even arrested in their own home after being falsely accused of absconding. Ultimately, faith in EM is as misplaced as Milwaukee advocate Amari Jones’ GPS signal when it identified him as being in the middle of Lake Michigan.

Harms of electronic monitoring

While little evidence exists to justify the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on electronic monitoring contracts around the country each year, firsthand accounts of the harms inflicted by EM are well-documented and plentiful, with folks such as long-time researcher and activist James Kilgore leading the charge.

Electronic monitoring creates huge financial burdens for many in already economically precarious positions

Electronic monitoring is often paired with conditions that restrict people’s ability leave their homes, thus severely limiting their ability to secure and/or maintain employment. People on EM may have to go through extremely complicated and lengthy processes just trying to gain approval to go to a job interview, and they may be able to work only on a fixed schedule or in a fixed location, precluding the flexibility required to work in industries like food service, waste management, or construction. Of course, these are some of the main industries in which many people impacted by the criminal legal system are able to find employment—when they can find employment at all.

Though some jurisdictions, including Illinois, have eliminated user fees for electronic monitoring, many programs charge anywhere from $1.50 to $47 per day, with a potential initial enrollment fee of up to $300 for the “privilege” of being imprisoned in one’s own home instead of in a jail or prison cell. Some have challenged these rates as extortion, particularly as agreeing to pay these fees they can ill afford may be the only way some can get out of jail to take care of their children or receive medical care.

Electronic monitoring limits access to healthcare while exacerbating or creating physical and mental health issues

Electronic monitoring doesn’t just jail people in their homes and strain their finances, it can also negatively impact their health—both physical and mental. People on EM often report being denied permission to simply go to the doctor or to the pharmacy to have life-saving prescriptions filled.

Moreover, the devices themselves can be a source of acute physical and mental trauma. A survey of individuals subjected to EM by ICE found that an astonishing 90% experienced harm to their physical health due to their time on EM. Those monitored may experience physical harms such as open sores and even electrical shocks. Likewise, the negative impact on mental health created by the stigmatization and isolation imposed by the devices has often been noted by those subjected to EM, with some reporting depressive and even suicidal thoughts. Others have reported that EM can be a trigger for those combatting addiction issues, which could potentially lead not only to new offenses, but relapse, overdose, and even death.

Electronic monitoring reinforces racial disparities and undermines families and communities of color

While the focus here has been primarily on the individual monitored, many harms are also inflicted upon the family and the overwhelmingly Black and Brown communities from which they come. Electronic monitoring impedes a person’s ability to take their kids to school or to doctor appointments, to engage in key family events such as the birth of the child or a funeral, and, as some have noted, has been used in an attempt to turn those who seek justice for their communities into “cautionary tales” for others in order to undermine social justice movements.

Conclusion

While this litany of the harms of electronic monitoring is expansive, it is far from exhaustive. As those directly impacted have told us time and again, there is no part of life that EM does not make more difficult, and as studies have shown there is little evidence to support EM as a viable alternative to incarceration. These are facts the Office of Statewide Pretrial Services should have taken into consideration as Illinois began its move into the realm of Pretrial Fairness.

Footnotes

-

In their reference guide on the use of Electronic Monitoring, the Federal Courts note: “GPS drift points can be the result of the following: thickness of the ionosphere, satellite orbit, humidity, or multi-path distortion (GPS bouncing off buildings).” ↩