Jailing the homeless: New data shed light on unhoused people in local jails

Our analysis of Jail Data Initiative data confirms the troubling practice of shuffling unhoused people into jails, at enormous moral and fiscal cost.

by Leah Wang, February 11, 2025

Local jails, which hold one out of every three people behind bars, have become America’s misguided answer to problems faced by the most vulnerable people, like poverty and homelessness. Despite jails’ central role in mass incarceration, comprehensive national data about the 5.6 million people who cycle through them each year is collected infrequently, leaving even basic questions about jails unanswerable.1 Fortunately for researchers, advocates, journalists and many others, the Jail Data Initiative is collecting present-day data from roughly 900 jails to provide a better understanding of those who are criminalized and locked up, including the approximately 205,000 unhoused people who are booked into jails each year.

In this briefing, we present what we know about unhoused people who are booked into jails, using the best available dataset, collected from jail rosters2 by the Jail Data Initiative (JDI). (Last year we published our first analysis of JDI data, focused on repeat bookings; we intend to publish additional analyses this year.) We find that people booked into jail who were marked as unhoused at intake are held for longer than average, while being handed some of the lowest-level charges like trespassing or petty theft.

As we’ll explain, the data have limitations, and some jails are simply not collecting important demographic data such as housing status. But we know that jurisdictions have grown increasingly hostile toward people with nowhere to call home: Instead of extending a helping hand to people simply trying to rest, eat, or otherwise survive, local law enforcement is handing them a criminal record and further destabilizing their lives.

Key findings

Only 20% of the jail rosters in the full dataset (175 of 889) contained one or more entries indicating an unhoused person, but the data from those jails suggest that cities and counties are turning to their jails to address behaviors that unhoused people often engage in because they are unhoused and/or poor.

Note: When referring to “unhoused people,” we mean those who are known to us to be unhoused, based on the jail roster data; everyone else may or may not have housing, but it’s unknown. As such, we also don’t know about people entering jails who are facing housing insecurity. For more information on our process, see our methodology section.

- About 4.5% of jail bookings in our sample are of unhoused people: Across the 175 jail rosters in our dataset, there were 22,839 bookings of people known to be unhoused, out of 503,571 total bookings over the course of one year. These bookings represent over 15,000 unique unhoused individuals (and about 406,000 people whose housing status was unknown, or who were housed, before their admission to jail.) This translates to about 205,000 different unhoused people going to jails each year nationwide — nearly one-third of the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night in 2023.3

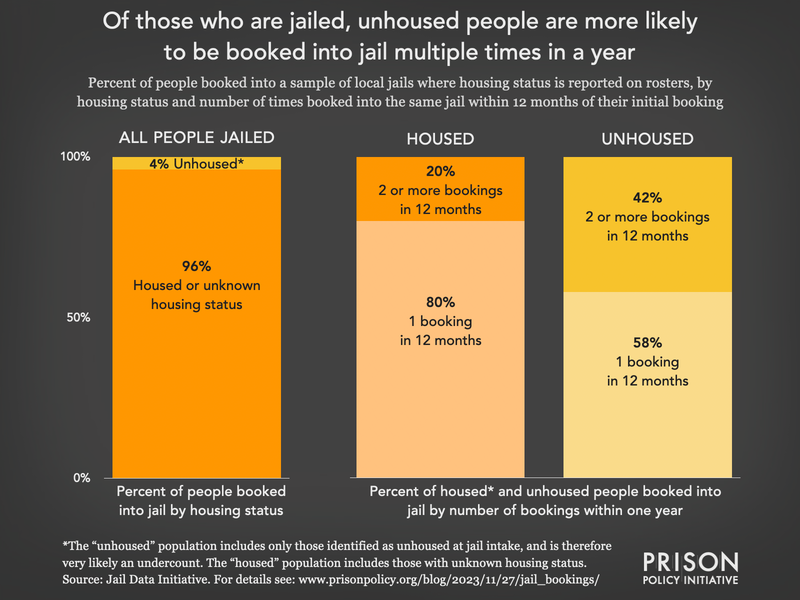

- Unhoused people are more likely to be booked multiple times: More than one out of every five jailed people are booked again within a year. Unhoused people made up a disproportionate share of those rebooked, representing 4% of all unique jail bookings but 8% of those rebooked. Said another way, over 40% of unhoused people booked into jail were booked multiple times, while only 20% of people who were housed or had an unknown housing status were booked multiple times. This finding affirms many observations of ineffective targeting and sweeps of homeless populations.

- Unhoused people are held in jails for longer than average: The overall average stay in jails whose rosters included at least one unhoused person was 21 days, but for unhoused individuals was 32 days — almost 50% longer. We also looked at median length of stay, because the average could be skewed by very long or very short jail stays. The median length of stay for all bookings in this sample was 4 days, but for unhoused individuals was 14 days — which is 2.5 times longer. Our analysis didn’t include bond (bail) amounts, but it’s safe to assume that unaffordable cash bail is keeping many unhoused people in jails longer than those who can afford it.

- People aged 55 and older make up a disproportionate share of bookings of unhoused people: About 10% of all jail bookings in our sample were older people (those age 55 or older), but 15% of bookings of unhoused people were older people. It’s important to note that older adults are more likely to spend 50% or more of their income on rent compared to people in other age groups, making them severely housing-cost-burdened and closer to housing insecurity or homelessness.

- The mass jailing of unhoused people overburdens Black people: While Black people accounted for 31% of all bookings, they accounted for 40% of all bookings of unhoused people. Meanwhile, white people made up 62% of all bookings but only 55% of all bookings of unhoused people. Similarly, people of color are overrepresented in the unhoused and severely housing-cost-burdened populations.

- Unhoused people face a litany of unfair criminal charges simply because they’re unhoused: In general, most people are jailed on public order, property, or drug charges, but bookings of unhoused people made up a disproportionately large share (8%) of bookings where the most serious charge was a property charge, and a slightly greater-than-expected portion (4.8%) of bookings for which the most serious charge was a drug charge. Unhoused people were most commonly booked for a top charge of trespassing — a charge frequently used to criminalize people for having nowhere else to go. They were also more commonly booked for possession of amphetamines, disorderly conduct/drunkenness, and petty theft (of less than $500) compared to all jail bookings in our sample. In contrast, bookings of unhoused people made up disproportionately small shares of bookings where the top charge was “violent” (3%), or related to DUI (<1%) or criminal traffic (2.1%) offenses.

Inconsistent data collection in jails leaves gaps in understanding

Although the data suggest that U.S. cities and counties are unnecessarily and excessively jailing unhoused people, 4% of jail bookings is a significant underestimate of unhoused people in local jails. Our methodology relies on positively identifying people as unhoused, but many more unhoused people may have chosen to list a shelter address, a family member’s address, or another location as their address when they were booked into jail.

And clearly, housing and other demographic data are not consistently collected by jail jurisdictions. While jail rosters are by no means a traditional source of data, it’s telling that only 20% of the nearly 900 rosters in the Jail Data Initiative’s sample recorded even a single person as unhoused during the yearlong study period. Smaller jails, in particular, were underrepresented in our dataset and may be less likely to record housing status information: Jails with an average daily population of less than 100 people made up 26% of our dataset, but make up 54% of jails across the U.S.

Criminalization will never solve homelessness

While not the complete picture of jails that we all wish for, the Jail Data Initiative data provide the best and most recent look at our national reliance on jails for addressing the ongoing crisis of homelessness. Our analysis reveals that unhoused people in jails are kept there for longer, are more likely to be booked multiple times, and are disproportionately Black. In total, over 200,000 unhoused people are coming in contact each year with law enforcement agents who are supposed to be keeping them safe, but the thinly veiled case for bringing them to jail only exacerbates their homelessness4 and despair.

There may be reports of unhoused people “choosing” to go to jail over sleeping in the streets, suggesting that jail is an acceptable solution. But it’s been shown time and time again that providing housing, services, and treatment instead of jail incarceration is more sustainable, a huge relief for taxpayers, and much less harmful to individuals. This is where diversion programs and permanent supportive housing can be utilized, before someone is arrested — better yet, before any police encounter.

Methodology

The Jail Data Initiative (JDI) collects, standardizes, and aggregates individual-level jail records from more than 1,000 jails in the U.S. every day. These records are publicly available online in jail rosters — the online logs of people detained in jail facilities that often include some personal information like name, date of birth, county, charge type, bail bond amounts, and more. JDI uses web scraping — the process of automating data collection from webpages — to update their database of jail records daily. The more than 1,000 jails included in the JDI database represent more than one-third of the 2,850 jails identified by the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Census of Jails, 2019 and are nationally representative.

For the purposes of our analysis of unhoused populations, we limited the JDI sample to bookings with admission dates between July 1, 2023 and June 30, 2024 from 175 jail rosters for which at least one person was categorized as “unhoused” upon intake (except when looking at rebookings; see below). To do so, our partners at JDI searched parts of the “Address” field in jail rosters for words like “homeless,” “unhoused,” “transient,” and similar keywords, then dropped rosters and/or bookings that did not meet our standards for robustness.

In all, there were 503,571 jail bookings captured across these 175 rosters, representing over 420,000 unique individuals booked into jail. Because our sample of jails for this analysis is so much smaller than the full JDI sample, ours may not be nationally representative.

Of course, not all of the jails included in the Jail Data Initiative database provide the same information. For the more detailed analyses of jail bookings by demographic and other characteristics, we used subsets of this sample due to inconsistencies in data collection:

- Length of stay: This sample included 440,120 bookings from 175 jail rosters.

- From the original sample described above, bookings were removed due to potential issues with date range overlap or missingness. Next, any active bookings as of the end of the date range (2024-06-30) were excluded.

- Rebookings: This sample included 599,423 bookings from 140 jail rosters. To look at unhoused people booked into jail multiple times, we began with data from 648 jail rosters for which there was available data for a two-year window (July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2023), plus an additional 365 days for a look-forward review of rebookings (to June 30, 2024). We looked at people who were both booked into jail and released within the two-year study period, and counted people as “rebooked” or “booked two or more times” if they were booked into the same jail system within 365 days of their first jail admission in the study time period. We elected to use a two-year time frame to capture a larger sample of bookings than we could in a single calendar year. From this sample of 648 jail rosters, there were 140 rosters that included at least one individual categorized as unhoused upon admission for any of their bookings.

- Gender: While we did look at the gender distribution of unhoused bookings, we did not find a notable difference between bookings of unhoused people and those whose housing status was unknown. The sample here included 477,363 bookings from 167 jail rosters, where at least one person was categorized as unhoused and where sex and/or gender was also reported.

- Race and ethnicity: This sample included 401,544 bookings from 138 jail rosters, where at least one person was categorized as unhoused and where race and/or ethnicity was also reported.

- Age: This sample included 448,273 bookings from 155 jail rosters, where at least one person was categorized as unhoused and where age was also reported.

- Charge type: This sample included 437,241 bookings from 173 jail rosters where at least one person was categorized as unhoused and where the charge type was also reported. Charges were standardized by JDI into both broad categories (Violent, Public Order, Property, Drug, DUI Offense, and Criminal Traffic) and more specific offense types, as described by the Uniform Crime Classification Standard (UCCS) schema. An overall “top charge” category per person was determined by selecting the most severe charge from among all bookings for an individual.

For more information on how JDI standardizes the terms in their data, please see their documentation page at https://jaildatainitiative.org/documentation/glossary.

Footnotes

-

Unbelievably, the 2002 Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (SILJ) is the most recent, nationally representative data available on people held in local jails (whereas an annual Survey of Jails and occasional Census of Jails capture some demographic information, but only from administrative records). The SILJ collects information like who is held pretrial due to inability to afford bail; the racial distribution of people detained pretrial; and what offenses people are locked up for before trial. The next edition of the SILJ was sent out to respondents in late 2024, a full 17 years off-schedule. ↩

-

A jail roster is a publicly available, online log of all individuals detained in a jail facility (or in some cases, multiple facilities or counties) on a given date. Jail rosters are typically updated daily, hourly or even in real-time, and contain information obtained at booking, like someone’s basic identifying information, where they were arrested, and the dollar amount of their bond.

↩ -

To estimate the number of different (unique) unhoused people booked into jail in a year, we started with the share of unique individuals in our sample, 3.63% (or 15,297) who were known to be unhoused. We applied this percentage to the number of unique individuals booked over the year from July 1, 2022 to June 30, 2023, which was 5,658,992, yielding our estimate of 205,268.

↩ -

There isn’t a plethora of research showing that jail time sustains homelessness — though studies out of Colorado and New York City suggest this is the case — but prison incarceration increases one’s likelihood of homelessness upon release by ten times. ↩