Rolling back solitary confinement reforms won’t make prisons safer

Thousands of New York prison guards went on strike to demand changes to the HALT Solitary Confinement Act. They claim limitations on solitary confinement have worsened working conditions. Here’s why the decision to return long-term isolation to New York’s prisons won’t fix things.

by Emmett Sanders, April 11, 2025

While the international community has long recognized solitary confinement as a form of torture, in the United States, the practice is as ubiquitous as the prison system itself. A 2023 report from Solitary Watch noted that on any given day more than 80,000 people in U.S. prisons are held in solitary confinement. People may spend months or even years in isolation, with devastating results. The HALT Solitary Confinement Act (HALT), passed in 2022 and advanced by the New York Campaign for Alternatives to Isolated Confinement (many of whom are themselves survivors of solitary confinement), was intended to change this for people in New York’s prisons. While this legislation did not eliminate the use of solitary confinement altogether, it made important changes like limiting stays to 15 days at a time, initiating review practices, and providing protections for vulnerable populations like the elderly, pregnant people, and those with mental or physical disabilities. However, as in many places that have attempted solitary confinement reform, these efforts have been met with resistance.

In February, correctional officers across the state of New York began a “wildcat” strike, an unsanctioned work stoppage in violation of New York law. For 22 days, around 15,000 correctional staff across 42 prisons refused to work, forcing Governor Kathy Hochul to call in the National Guard as a stopgap measure. As might be expected, incarcerated people bore the brunt of harm of the strike; at least seven incarcerated people died during the strike. There were also reports of insufficient medical care, dangerously filthy living conditions, and the interruption of programming and visitation. Striking corrections officers’ representatives claim the strike was a desperate response to deteriorating working conditions and understaffing, much of which they blame on HALT.

Ultimately, Hochul gave in to strikers’ demands to rescind HALT protections, first temporarily suspending them, then later agreeing to extend this suspension pending further evaluation,1 a move that illegally sidesteps the legislative process.2 The rollback of HALT protections leaves people in prison once more subject to extended isolation in solitary confinement. It will also do little to improve working conditions or to fix staffing concerns and stands to make prisons even less safe.

Unpacking the claim that solitary reforms have compromised safety

Strikers’ claims that the HALT Act’s restrictions have hamstrung correctional officers’ ability to maintain order is dubious at best. This is largely because many prisons have simply ignored HALT provisions, routinely violated the law, and have continued to use solitary confinement in much the same manner as before. New York’s Office of the Inspector General, as well as a June 2024 court ruling found that:

- 40% of people were held in solitary confinement longer than the law allowed;

- 24% of the time, people were held without sufficient evidence of a segregable offense;

- People were routinely held hundreds of days past the 15-day time limit without sufficient review;

- People with disabilities have also continued to be thrown in solitary; and

- The head of the prison system even issued a blanket order to use restraints for all out-of-cell activities, in direct violation of the law.

Correctional officers’ claim that a tool has been taken out of their toolbox is disingenuous when that tool is still being used every day, and in much the same way it was before the law changed. Simply put, you cannot attribute a rise in violence to a change in policy when you have refused to implement that policy.

Dubious statistics around rising staff assaults

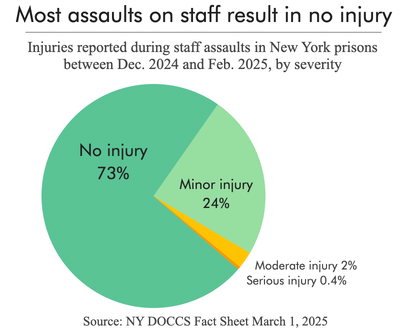

Reports do show rising numbers of assaults on staff as well as on incarcerated people. However, this rise predates the implementation of the HALT Act by several years. Between 2012 and 2014 the number of assaults on staff nearly doubled. In fact, both the number of staff assaults and the rate of staff assaults per incarcerated person have risen every single year since 2016. Thankfully, the vast majority of incidents result in “no injury” at all to correctional staff staff and most others result in “minor injuries” that “require no or minimal treatment.”3 It is also worth noting, like the department of corrections itself does, the distinction between assaults as defined by penal law, “which require physical harm,” and assaults as defined by department policy; according to its policy, “events where no physical injury occurs and events where any object, including a small object, is thrown at and hits another person” can result in assault reports. While this current spike is concerning and should be investigated, formerly incarcerated advocates also point to a history of correctional staff falsifying reports and weaponizing the disciplinary process to cover up a culture of abuse. One formerly incarcerated survivor of abuse at the hands of correctional officers noted, “They control the statistics.“

Skepticism also surrounds the timing of the strike, which comes just as the department faces public outcry after correctional staff accidentally videotaped themselves beating an incarcerated man, 43 year-old Robert Brooks, to death in December. More than a dozen correctional staff were indicted in the case on February 20th, which drew national attention. Critics point to previous work stoppages which coincided with allegations of abuse and increased scrutiny.

Claims that changes in the use of solitary confinement are responsible for a massive staffing shortage in New York Prisons also bear closer scrutiny. Most jails and prisons across the country have not implemented reforms to solitary confinement, but have seen similar recent reductions in staffing levels. While physically and mentally hazardous working conditions are certainly a contributing factor, they are far from the only reason. In fact, in a recent survey by Corrections Today, the top three reasons people reported leaving corrections were work-life balance, pay, and a lack of flexibility in schedule. Safety concerns ranked 8th on the list of 15.

Prisons are not understaffed, people are over-incarcerated

Moreover, prisons are not understaffed, but rather people are over-incarcerated. In New York, much of the problem lies in the fact that despite massive reductions in the prison population that have far outpaced reductions in staff, correctional officers and politicians alike have actively opposed efforts to decarcerate. While New York has managed to close a number of prisons since 2011, saving taxpayers more than $492 million, these efforts have been met with resistance and, at times, resignations from correctional staff. They persist in fighting to keep prisons open, even when they are two-thirds empty, when these facilities could be closed and their resources reallocated. Their argument is that closing prisons will bring economic collapse to small towns. These claims underscore that incarceration is indeed an industry in which the primary end-product is human misery. They are also patently untrue; prisons actually weaken rural economies.

A closer look at the numbers shows how problematic this insistence on keeping unnecessary prisons open actually is. Since 2003, the number of prison staff has fallen by just over 32%. However, New York’s prison population has fallen by more than 49% over that same period of time. Indeed, while prison staff dropped around 6% between 2020 and 2021, the incarcerated population dropped nearly 11% that same year and had fallen 22% the year before.

Perhaps most interestingly, the ratio of correctional staff to incarcerated persons stood at 1:2.4, or around one staff member for every 2 to 3 people incarcerated in New York prisons. This ratio is actually better than in 2018. In fact, the most recent national data show that New York prisons have the best staff-to-incarcerated person ratio in the nation. However, this is undercut by maintaining prisons that are far below capacity, largely because of, as the Department of Corrections notes, “the security needs that exist in the facilities regardless of the incarcerated individual population.”

Solitary confinement doesn’t prevent harm, it creates it

Counter to strikers’ claims that the use of solitary confinement is necessary to maintain safety, isolating people who often already have mental health support needs in prison conditions that impair emotional, social, and cognitive function does not make anyone safer. Solitary confinement doesn’t reduce prison violence, nor does it make people rush to fill out applications for prison jobs and make prisons better staffed. What is does do is create lasting harm that shortens people’s lives, devastates their mental and physical health, has been associated with heightened risk of suicide and self-mutilation, and further entrenches racial and gender disparities in the prison system. Even worse, perhaps, solitary confinement has actually been shown to diminish public safety by increasing the chances of a return to prison after people come home. Research has repeatedly shown that reducing the use of solitary confinement significantly reduces prison violence.

Ultimately, the crisis in New York prisons is one of an ongoing commitment to brutality rather than a crisis of capacity, and it is not one that will be resolved by doubling down on state-sanctioned torture and abuse. If New York wants to resolve the capacity issues that strikers claimed were at the heart of their protest, the state needs to address the real issues, rather than attack a humane reform that has never fully been implemented. HALT’s provisions should be fully reinstated, and, as incarcerated journalist Eric Williams rightfully points out, the state should implement legislation, and common-sense policies that can safely and cost-effectively further reduce New York’s prison population. Most importantly, the state should continue to close unnecessary prisons and fund new forms of economic development in these rural communities that don’t rely upon the narrative that incarcerated people are, as one New York legislator has claimed, “the animals of society.“ They are not. They are family members and loved ones. They are human beings, and they should not be subjected to torture.

Footnotes

-

The state also agreed to make significant changes to overtime, and to rescind a recent memo from the DOCCS Commissioner which instructed prisons at 70% of staffing levels to consider themselves fully staffed. ↩

-

Many staff refused to return to work even after the deal had been reached, resulting in more than 2,000 firings. ↩

-

Per New York DOCCS: “Minor injuries are those that require either no treatment, minimal treatment (scratch, bruise, aches/pain) or precautionary treatment. Moderate injuries are those such as lacerations, concussions, 2nd degree burns, serious sprains, dislocation, and muscle or ligament damage. Serious injuries are those that require transport to an outside hospital but are not considered life-threatening at the preliminary report. Severe injuries are those that cause obvious disfigurement, protracted impairment of health, loss or impairment of organ function, amputation, and injuries that risk cause of death.” ↩