Shadow Budgets: How mass incarceration steals from the poor to give to the prison

Revenues from communication fees, commissary purchases, disciplinary fines, and more flow into “Inmate Welfare Funds” meant to benefit incarcerated populations. However, our analysis of prison systems across the U.S. reveals that they are used more like slush funds that, in many cases, make society’s most vulnerable people pay for prison operations, staff salaries, benefits, and more.

By Brian Nam-Sonenstein

May 6, 2024

Press release

Reporter guide

- Table of Contents

- Are welfare funds helpful or exploitative?

- How welfare funds subsidize mass incarceration

- Shifting state responsibilities onto incarcerated communities

- Flagrant abuses of welfare funds

- Sitting on cash while needs go unmet

- Should welfare funds exist at all?

- Recommendations

- Appendices

Prisons and jails generate billions of dollars each year by charging incarcerated people and their communities steep prices for phone calls, video calls, e-messaging, money transfers, and commissary purchases.1 A lot of that money goes back to corrections agencies in the form of kickbacks. But what happens to it from there? As it turns out, much of this money flows into special accounts called “Inmate Welfare Funds.”2 These welfare funds are supposed to be used for non-essential purchases that collectively benefit the incarcerated population. In reality, poorly written policies and lax oversight make welfare funds an irresistible target for corruption in jails and prisons: in many cases, corrections officials have wide discretion to use welfare funds as shadow budgets for subsidizing essential facility operations, staff salaries, vehicles, weapons, and more, instead of paying for such things out of their department’s more transparent and accountable general budget.3

How do welfare funds get funded? How is the money used, and who gets to decide? We analyzed laws and policies governing welfare funds in all 50 state prison systems and the federal Bureau of Prisons to find out.5 We identified at least 49 prison systems that have some form of welfare fund, though it’s likely that every system has one.6 In most cases, they are funded through communications fees and store purchases, as we mentioned, as well as interest accrued on individual trust accounts.7 Some prison systems also fund them with sums of money confiscated from people who escape custody, contraband, or disciplinary fines.

Although welfare funds are generally meant to be used for recreation equipment, entertainment, social and educational opportunities, and other non-essential benefits for the incarcerated population as a whole, prison policies frequently allow them to pay for facility construction and maintenance, hygiene products for indigent people, release-related costs8 and other goods and services that are supposed to come out of a department’s general budget. Our analysis reveals that most policies are so vague that prison officials enjoy wide discretion to spend incarcerated peoples’ money as they please — sometimes spending it on luxury perks for staff.

How prisons build up welfare funds — and get away with spending other people’s money as they please

| Revenue policies | Expenditure policies |

|---|---|

| 39 prison systems draw revenue from commissary purchases | 9 prison systems can spend the money on capital projects, such as construction, improvement, and maintenance of facilities |

| 19 prison systems draw revenue from communications kickbacks, like telephone, email, and video calling user fees | 16 prison systems can spend the money on educational programming and related supplies |

| 3 prison systems draw revenues from disciplinary fines | 6 prison systems can spend the money on various needs for indigent incarcerated people |

| 14 prison systems draw revenue from confiscated funds, including contraband or the accounts of people who escape prison | 2 prison systems allow the money to be used for loans for incarcerated people9 |

| 16 prison systems have vague language that permit wide discretion for identifying revenue sources | 25 prison systems allow wide discretion for the use of funds by using language like “primarily” or “including but not limited to” in expenditure policies |

| 16 prison systems draw revenue from interest earned on deposits into individual trust accounts for incarcerated people | 12 prison systems ban specific uses of funds, such as purchasing goods and services the department is obligated to provide |

| 10 prison systems allow the money to be spent on release-related costs, like pre-release programming, transportation, gate money, or housing | |

| 9 prison systems allow the money to be spent on self-help programs like Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous, or on expenses related to treatment programs | |

| 17 of the 49 prison systems with welfare funds we could identify did not have language specific to fiscal reporting or audits of their funds | |

Only 12 prison systems (24%) explicitly prohibit certain kinds of spending, while roughly one-third do not specify any transparency or oversight measures for these accounts. Some prison systems earmark a portion of the money to be transferred to other funds: in Florida, revenues in excess of $32 million must be sent to the state’s general revenue fund, while Arizona requires $500,000 be transferred from their welfare fund to the corrections building renewal fund.10 In states like Iowa, North Carolina, and West Virginia, funds can be used on expenses relating to victims’ compensation or reimbursing victims’ travel expenses. Meanwhile, journalists have uncovered multiple instances in which millions of dollars were extracted from incarcerated populations and not spent at all despite the extraordinary needs of people on the inside: prisons will sometimes sit on heaps of money while jails treat themselves to shopping sprees for bullets, break room supplies, and gift cards for honey-baked hams. These corrupt practices11 shift essential costs—historically the responsibility of governments—to incarcerated people and their support networks and, in the process, often force women, low-income families, and communities of color to subsidize mass incarceration.

Are welfare funds helpful or exploitative?

The rationale behind these welfare funds is complicated, controversial, and contested among advocates and incarcerated people.12 Some believe it’s useful for incarcerated people to have a pool of money that can be used for their collective benefit13 and argue that, if these funds are going to exist, incarcerated people should have greater decision-making power over how their money is spent, and officials should be more accountable in terms of their use. Others argue welfare funds should be abolished on the principle that fees and fines should not be extracted from incarcerated people and their communities, and state and local governments should bear the full financial burden of incarceration. Notably, in some places, incarcerated people seem unaware these funds even exist because their balances and expenditures are not shared with the population.

The widespread lack of oversight and accountability plays a role in all three of these positions. Roughly one-third (17 out of 49) of prison policies do not mention any form of oversight or transparency measures for their welfare funds.14 Among the 32 other prison systems with welfare funds, policies mandate a range of annual or biannual audits and reports that summarize revenues and expenditures. These audits and reports are variously required to be submitted internally — to wardens, department fiscal offices, or deputy directors, for example — or externally to controllers, comptrollers, governors, legislators, or other bodies. In some cases, there is no clearly defined schedule for reporting: Indiana, for example, specifies that “periodic audits” be conducted by the State Board of Accounts. In Georgia, reporting is necessary only upon suspicion of fraud, changes in personnel managing the fund, or extensive funding shortages. Meanwhile, just five states — California, Kentucky, Maryland, Nevada, and Washington state — require that prisons post audits publicly within view of the incarcerated population.

Who exactly administers these funds, and how they go about doing that, is also unclear in many of the policies we reviewed. Typically, welfare funds are run by higher-ranking corrections officials, such as a warden, deputy warden, chief administrative officer, superintendent, director, commissioner, or one of their designees. Fourteen prison systems have some form of board or committee that governs the welfare fund, but only three — California, Minnesota, and Vermont — explicitly permit incarcerated representatives to participate. Mississippi, meanwhile, permits a relative of an incarcerated person to serve as a representative. Generally, the fund administrator is in charge of approving or denying expenditures and keeping track of the funds entering and leaving the account.15 Few policies explain how often these committees are supposed to meet, nor do they go into very much detail about their specific responsibilities — and whether a committee exists in policy is a separate matter from whether it operates in practice.

Given this context, incarcerated people and their support networks should not be forced to subsidize government responsibilities through welfare funds. Given the general state of (un)accountability in U.S. corrections,16 it will be a tall order to secure meaningful oversight and decision-making power over these funds. These piles of money seem irresistible to corrections agencies, and the potential for abuse and corruption is high. But in recognition of the lack of consensus about their place in corrections — including among incarcerated people — as well as the wide variation in welfare fund policy, practice, and political context, we offer several policy recommendations to help advocates and lawmakers mitigate their harms. Explained in greater detail in the Recommendations section below, these include:

- ending exploitative pricing schemes in communications and commissaries;

- revising policies on permitted uses and prohibitions to be more explicit;

- implementing independent oversight and granting incarcerated people greater decision-making power; and

- reducing the need to supplement corrections budgets through decarceration.

How welfare funds subsidize mass incarceration

It’s important that we get a sense of where welfare funds came from and how they fit into the broader economy of jails and prisons. There are unfortunately few histories available, but tracking the evolution of these funds in California provides a glimpse at the forces that have made them what they are today. California’s welfare fund was established in 1949. The idea was to permit sheriffs to sell tobacco, candy, and other items to the incarcerated population so long as the profits went into a fund intended for their general welfare. Originally, California’s welfare fund policy stipulated that they were “solely” to be used for the “benefit, education, and welfare” of incarcerated people and that normal expenses (like medical services and clothing) had to be paid for out of the sheriff’s general budget. That changed in 1993 when policy reforms permitted their use “to augment those required county expenses as determined by the sheriff to be in the best interests of inmates.” Those “best interests” were not specified, granting sheriffs wide latitude to spend the money as they wished. This shift coincided with a wave of privatization that gave us for-profit prisons and the outsourcing of communications and commissary services to corporate vendors. As privatization spread, welfare fund balances ballooned, and, in the process, became irresistible cash cows for corrections agencies.

Attorney and researcher Stephen Raher, who has fought the financial exploitation of incarcerated people and their communities for many years, coined the term “prison retailing” to distill how vendors like phone companies and commissary contractors transform state responsibilities into sources of revenue for themselves and their correctional agency partners. For example, when a prison system takes one of its responsibilities — like providing incarcerated people with phone services — and sells it off to a telecommunications company, it creates a new market. That market operates by charging fees to service users (incarcerated people and their communities), which enriches both the telecom company (in the form of profit) and the prison system (in the form of kickbacks). Prison systems deposit their kickbacks into opaque, unaccountable, and ill-defined funds allegedly intended for the “general welfare” of the imprisoned population, but which prison administrators can use on practically whatever they want. This carceral sleight of hand displaces the financial responsibilities of jails and prisons onto impacted communities and rebrands it as the selfless goodwill of corrections agencies. And though it may not seem like corrections staff directly pocket revenues from prison retailing, the reality is that subsidizing jail and prison operations contributes to their job security, if not directly funding their actual salaries and benefits.17

Herein lies a vicious cycle of exploitation in the form of an arms race for higher commissions: contractors make their money through commissions, and they ensure their future profits by rewarding corrections agencies with kickbacks that will entice them to renew their contracts. But bigger kickbacks require vendors to continuously raise prices to keep their profits growing. At the same time, corrections agencies come to rely on kickbacks to supplement costs that should be paid for out of their legislatively appropriated budgets.

Though welfare funds represent a comparatively small proportion of corrections budgets, the millions of dollars sapped from incarcerated people are nonetheless significant sums of money that jails and prisons do not need to secure from lawmakers. Without a transparent public budgeting process, corrections agencies can grow this shadow budget free from scrutiny and oversight. In the end, mass incarceration is to some degree supported by an inversion of welfare for the poor: as scholars Mary Fainsod Katzenstein and Maureen R. Waller explain, “Instead of serving as a source of support and protection for poor families, the state saps resources from indigent families of loved ones in the criminal justice system in order to fund the state’s project of poverty governance.”

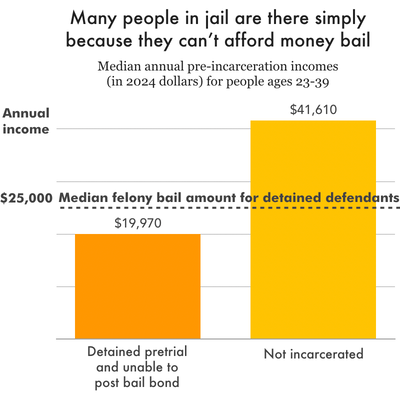

Median annual incomes are based on our 2016 analysis in Detaining The Poor, adjusted to 2024 dollars and rounded to the nearest ten dollars. The median felony bail amount was reported by Bureau of Justice Statistics in Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2009, Table 16.

In local jails, the incentives behind this practice are particularly egregious. Many people are detained in jails pretrial essentially because they are too poor to afford bail. For people who are unable to post a bail bond, the median annual income prior to incarceration in the United States is just shy of $20,000 per year.18 Considering roughly a quarter of all cases are eventually dismissed, this means a significant number of people who are arrested but never convicted of a crime nonetheless subsidize the punishment infrastructure. Put another way, welfare funds help jails supplement their budgets by levying fines and fees against large numbers of detained people who are only there because they cannot afford to leave. While we focused only on prison policies in our analysis, additional research is urgently needed for the thousands of jail systems nationwide that also have some version of these accounts.19 We were, however, able to explore some of the ways jails have used welfare funds thanks to the work of investigative journalists from around the country.

Bodycams, bullets, and new jails: Shifting state responsibilities onto incarcerated communities

How do prisons and jails use these funds if not for the “general welfare” of incarcerated people? And how do they get away with spending the money in these ways? Our analysis shows that, while some policies permit welfare fund dollars to be spent on things that should clearly be funded through a department’s general budget, others are written with language so broad that essentially nothing is off limits. For example, some policies will declare that the funds must be “overall” or “primarily” used for the general welfare of the population, or can be spent on goods and services “including but not limited to” specific uses.20 These few words provide significant wiggle room that corrections agencies readily exploit in the absence of meaningful oversight.

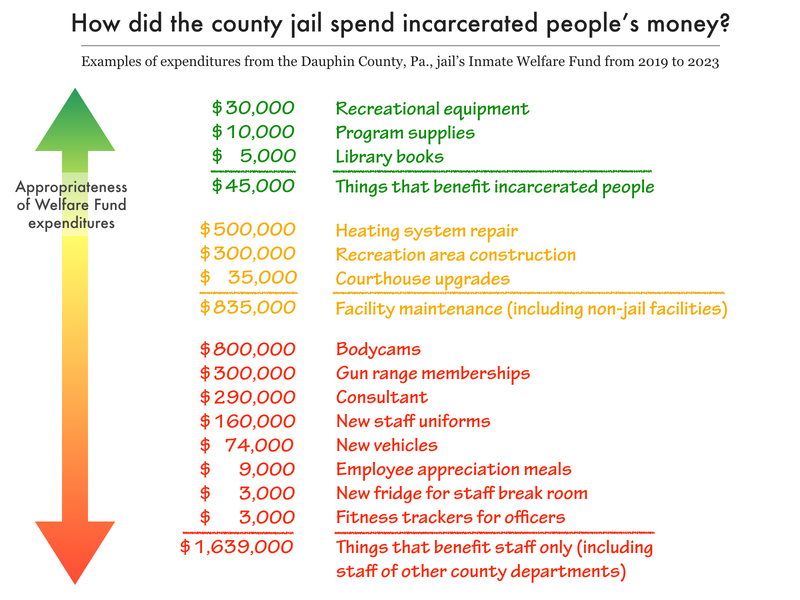

In some cases, money collected in the name of the “general welfare” of jailed populations is actually spent on staff. The Dauphin County (Harrisburg) jail in Pennsylvania, for example, collected $3.4 million between 2019 and 2023. A review of spending records by journalist Joshua Vaughn for PennLive found that the vast majority of welfare fund expenditures directly benefitted staff, not incarcerated people:

The PennLive article goes on to mention that a county spokesperson defended spending welfare funds on these staff perks, arguing that “the current job market makes it difficult to retain employees.”

Dauphin County also used substantial amounts of money from the welfare fund to pay for facility renovations — essential expenditures that inarguably should have been paid for from the county’s coffers. Half a million dollars was allocated to fix the aging HVAC system after an incarcerated person died having twice developed hypothermia, $300,000 went to building a fenced-in recreation area, and $35,000 was used to upgrade holding cells and benches at the courthouse.21 These are far from non-essential expenses that promote the welfare of the incarcerated population; they are basic costs associated with the daily operations of a jail — costs that should be exclusively borne by the department.

California provides further examples of corrections agencies using welfare funds to subsidize carceral infrastructure and personnel. The Butte County (Chico) Board of Supervisors attempted to use $650,000 from their jail’s welfare fund to build a new jail before the ACLU sued to stop them in 2016.22 Meanwhile, a 2021 investigation revealed that Sacramento’s sheriff spent more than $15 million in welfare fund dollars on staff salaries; $1.45 million to purchase a camera system; $1 million for parking lot improvements; $900,000 for radio leases, surveillance cameras, and software to track incarcerated people; and $150,000 for perimeter fences.

News reports and audits have uncovered other questionable uses of welfare funds. In Montana, an audit found that the Department of Correction had used thousands of welfare fund dollars to cover things that traditionally would be paid for by a department’s general budget: $5,200 for ice and water dispensers in the infirmary and $9,000 for hygiene and legal supplies for indigent people. An additional $12,000 was used to purchase computers for legal research — something auditors found particularly troubling “since it is well-established that adequate access to the courts […] is a state responsibility.” Arizona’s Pinal County (Florence) Sheriff spent over $4 million of welfare fund money between 2018 and 2023 — at least $217,000 (or 5.5%) of which was spent on guns, bullets, and vests for law enforcement while less than $900 (or 0.02%) was spent on books for people detained at the jail. In Colorado, the El Paso (Colorado Springs) County jail’s largest expenditure from their fund in 2021 was $664,000 to “MH Medical Services” (the sheriff declined to elaborate to reporters what exactly that was). And in Los Angeles, California, a 2021 audit of the jail’s welfare fund (which had a balance of nearly $26 million) noted that the “historical practice is to annually allocate and spend at least 51% [of welfare fund revenue] on inmate programs and up to 49% on jail maintenance.” The LA Auditor-Controller added that the department “may not be identifying additional inmate programs and other goods/services that provide direct benefits to inmates housed in the County’s jail facilities.” According to journalist Nika Soon-Shiong, “The sheriff cited ‘staff shortages and other priorities’ as reasons for its lackluster commitment to creating performance evaluation processes or delivering detailed IWF expenditure reports.”23

The San Diego Sheriff’s Department in California used welfare funds to “pay employee salaries, maintain department vehicles, buy gasoline, pay office expenses and even buy toilets at one jail’s recreational yard.” People jailed there faced sharp increases in commissary prices and obstacles to participation in enrichment programs at the very same time that the department was spending their money on staff cars and paychecks. When local reporters started asking questions, the San Diego sheriff “defended the spending as appropriate and noted that state law gives the department broad authority over how the fund is administered.”

Gift cards, flowers, and theft: Flagrant abuses of welfare funds

Using welfare funds to pay corrections agency bills is bad enough. But it’s arguably much worse to take money from the poorest people in society and spend it on ridiculous staff luxuries. Take the deeply troubled Fulton County jail in Atlanta, Georgia, for example. Last year, it was reported that officials had misused tens of thousands of dollars from the jail’s welfare fund:

- $40,000 purchased gift cards from The Honey Baked Ham Company for a staff holiday party.

- $5,000 was set aside for a Thanksgiving giveaway.

- $2,600 was paid to florists.

Additionally, reporters found a range of expenses that included a face painting booth, DJ services, a tropical bounce house, and more “linked to employee appreciation and community diversion.” When pressed on these outrageous expenditures, Fulton County Sheriff Pat LaBat responded that “There was no criminal intent” and that “everything that has come out of the inmate welfare fund has been spent on the betterment of the sheriff’s office” (our emphasis). Ultimately, it was the incarcerated population that suffered the consequences of this obvious corruption: the county abolished the fund altogether, and as a result, money that was supposed to be spent on blankets and mattresses for indigent people suddenly dried up. The future of all of the money that had accrued in that account—incarcerated people’s money—remains uncertain as it was sent to the county’s general fund.

In Minnesota, facility officials24 refused to purchase cable television for the incarcerated population using funds collected from people convicted of sexual offenses. Curiously, however, officials saw no problem with using thousands of dollars of welfare fund money to buy Netflix subscriptions that incarcerated people could not access. Officials claimed they couldn’t afford the cable subscription but resisted calls for transparency.

In other cases, welfare fund oversight is so lax or nonexistent that officials aren’t even sure where the money goes or how it’s spent. In Oregon, an investigation into stolen welfare funds ended because so little bookkeeping took place that they could not figure out which staff member ran off with the money. Back in Fulton County, Ga., Sheriff LaBat told reporters that “some things were paid out of the wrong account” and that people in the sheriff’s office had “made some bad calls about what to buy with the fund.” LaBat seemed not to know that there was supposed to be an oversight committee, of which he was supposed to be a member. When asked if the committee ever met, he said “not once have they met in my entire time being sheriff.” Robb Pitts, the chairman of the Fulton County Board of Commissioners, said he had “never heard of the [oversight] committee,” but added that it “sounds like a great idea.”

Sitting on cash while needs go unmet

While in many cases welfare fund dollars are misspent, other times they are not spent at all. This raises two important questions at once: first, are welfare funds even necessary? And second, why are jail and prison conditions so terribly austere with all this money lying around? Corrections agencies frequently push back on efforts to abolish phone and video calling fees or to severely limit kickbacks, warning that doing so would negatively impact people inside — but then we see evidence of those same corrections departments leaving money on the table while incarcerated people are left to languish, their most basic needs unmet.

Arizona’s Department of Corrections made this argument in 2015 as the Federal Communications Commission moved to limit kickbacks from phone calls. They argued it would lead to “reduced educational and job training opportunities…[which would]…have potentially life-altering negative impacts on inmates and their families, not to mention public safety in the community.” But what was actually going on with these funds at the time? Arizona reduced spending on education and programming by nearly 48% in four years — from $3.2 million in 2010 to $1.7 million in 2014 — while the department’s phone revenues steadily increased by 12% — from nearly $3.7 million in 2010 to $4.1 million in 2014.25 The overall welfare fund balance actually ballooned over this period, growing to $8.9 million by the end of 2014. So while Arizona complained that limiting kickbacks would negatively impact incarcerated people, the department was sitting on funds that could have covered education and other programs for at least five years before needing to earn a penny more.

Big unused welfare fund balances exist in other jails and prisons across the country: in Marin County (San Rafael), California, a third of the jail’s welfare fund balance went “to the benefit of incarcerated people,” a third went to the “inmate program coordinator” that manages the fund, and a third stayed in the fund, leaving behind a balance of $1.3 million. In Sacramento County, the balance stood at $7 million at the end of 2019. And in Maine, the Department of Corrections had a balance of $1.5 million across five prisons in 2021, while the York County (Biddeford) jail left nearly half a million dollars sitting in its account. Certainly, good governance necessitates leaving some money behind for unexpected expenses, but sitting on this much money while surrounded by such high levels of need is unconscionable.

Should welfare funds exist at all?

As we’ve examined throughout this report, welfare funds are as exploitative as they are unaccountable. They are frequently used to shift the financial responsibilities of jails and prisons onto communities impacted by incarceration, subsidizing their own occupational livelihoods in the process. Though in-name, welfare funds are designed to benefit incarcerated populations, as we have seen, they are more often used for the general welfare of corrections agencies.

Let us return to the question of whether these funds should exist at all. On the one hand, they theoretically could be used to accumulate resources that could be used for non-essential goods and services that could make life in jail or prison a bit more bearable. On the other, they are unaccountable and opaque, making them ripe targets for corruption, whether that be misuse or no use at all. Our research has left us with serious doubts as to whether the promise of welfare funds can ever be fully realized. The immense power imbalance between corrections officials and incarcerated people and the general lack of oversight in correctional spaces make it doubtful that incarcerated people could collectively and reliably be given meaningful control over the use of these funds. And given the disproportionate levels of poverty facing criminalized people, it’s even more difficult to justify the financial extraction that supplies welfare funds with money in the first place.

While we think state and local governments should, on principle, be forced to accept full financial responsibility for the costly policy choice of incarceration, we also realize that these funds may continue to exist in one form or another for some time. Given this reality, we have collected some policy recommendations for dealing with welfare fund corruption and for empowering incarcerated people and their communities in their use.

Recommendations

Place financial responsibility where it belongs

Incarceration is already experienced as one big financial sanction from arrest forward. So long as they choose to incarcerate, states and local governments must take all necessary steps to avoid offloading the costs of incarceration onto people and their families. Here, we must be explicit: we are not advocating for expanding corrections budgets; instead, we are calling for a change in revenue streams away from the shadowy system of prison retailing and toward existing department budgets that are publicly appropriated by legislatures. This shift alone should somewhat increase transparency and accountability, though it is not enough on its own.

In particular, state and local governments should cover the costs of life’s necessities for all incarcerated people — including indigent people — such as sufficient hygiene products, healthcare, nutritious food, and access to regular communication through postage, phone calls, and other technologies. These should not be placed out of reach (or require personal sacrifice) for anyone who is in jail or prison or supports someone who is. This also goes for education, medical care, treatment, and job training. Furthermore, there should be a categorical ban on using these funds for anything related to staff or operations, including staff salaries, benefits, and extracurricular activities, as well as any costs related to facility maintenance or construction.

Money generated from incarcerated labor (excluding wages),26 interest accrued on trust accounts that is not returned to the account holder,27 and revenues generated from the sale of hobbycrafts are examples of revenues that we imagine are less problematic to be deposited into welfare funds. Such revenues should not be diverted to departmental, municipal, county, or state general budgets, as sometimes happens, but should be maintained for the actual benefit of the incarcerated population. It is their money, and they should be able to use it.

Give decision-making power to the people who pay into welfare funds

As we have discussed, some prison systems have created committees to look after welfare funds and approve expenditures.28 However, these committees are most often entirely made up of wardens and other corrections staff. Though some committees do have incarcerated or family representatives, this is far from the norm, but it should be the bare minimum if incarcerated people are not given full decision-making power over how their own money is spent.

Impose independent oversight, transparency, and accountability

Jails and prisons are in desperate need of independent, external oversight in general. Until we get there, we can advocate for basic oversight of welfare funds wherever they exist. In some places where giving control to incarcerated communities is not an option, advocates may want to consider removing welfare fund responsibilities from corrections departments entirely, as Mississippi did when it handed control of the fund over to the state treasurer. Regardless of who administers the fund, there must be transparency on revenue sources and expenditures: the incarcerated population should know how much money is coming and going, as should the non-incarcerated public. There should be a public accounting of how much money is leftover in the account from year to year as well.

Policies, in writing and in implementation, should be strengthened with regard to the efficient and effective expenditure of these funds. They should be clearly written, precise, and detail-oriented, rather than vague and completely open to the discretion of corrections officials. Among other considerations, they should not, for example, allow welfare fund dollars to be squandered on projects just for the sake of spending it, or used to make expensive purchases when something less expensive at a similar quality is available. In other words, these funds need and deserve stewardship that works in the best interest of incarcerated people.

Short of this, journalists and members of the public should know that this information is a public record and can be accessed through a public records request. State and local auditors and comptrollers should take a close look at these funds in their jurisdiction — particularly in places that administer funds on the facility level and leave decision-making power to facility leadership.

Decarcerate

Last but most importantly, if jails and prisons are struggling so badly that they feel the need to draw money from welfare funds to fix their HVAC systems, pay staff salaries, or cover tens of thousands of dollars in ham gift cards, the problem is surely not one of resources but of incarceration as a policy choice. If the more than $81 billion spent annually on corrections agencies is still not enough to fund the obligations of incarceration — which has at this point little if any discernable effect on crime rates but glaring negative consequences for society — then perhaps this carceral welfare scheme is a sign that it’s long past time to change course. It would be far wiser to embrace the many other approaches to harm and health that we at least know make people safer. Reducing arrests and correctional populations, as well as downsizing the punishment infrastructure, should reduce expenses for corrections agencies while also serving as a stimulus for just about every level of government. At least then there will be money that can be invested into the communities that need it most: the same communities forced to pay into jail and prison welfare funds today.

Get our latest data & analysis in your inbox!

About the author

Brian Nam-Sonenstein is a Senior Editor and Researcher at the Prison Policy Initiative. He is the author of several publications, including briefings on the suppression of prison journalism, the importance of housing in disrupting cycles of incarceration, and the misrepresentation of “failure to appear” as a public safety issue. In addition to his work as a researcher, Brian plays a pivotal role in supporting other members of the Research Department in shaping the framing and messaging of their publications in a way that maximizes their impact and reach.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. The organization is most well-known for its big-picture publication Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie that helps the public more fully engage in criminal justice reform. This report builds upon the organization’s work advocating for fairness in industries that exploit the needs of incarcerated people and their families, including those that control prison and jail telephone calls, video calls, and money transfers.

Acknowledgments

All Prison Policy Initiative reports are collaborative endeavors, and this report is no different. The author would particularly like to thank current staff members for their insights and guidance, as well as Stephen Raher for the framing and research he contributed. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Andrew Mulhearn for the artwork for this report, as well as Claude Lacombe, Stevie Wilson, Lawrence Jenkins, and others who shared their insights as we conducted our research. Lastly, we would like to thank our donors who make this work possible.

Appendices

Appendix A — Prison system “Inmate Welfare Fund” policies

Prison system “Inmate Welfare Fund” policies for all 50 states and the federal Bureau of Prisons as of May 2024

Appendix B — Sample of specific welfare fund revenue sources, expenditures, prohibitions, and vague terminology

The following table provides a small sampling of the revenues, expenditures, prohibitions, and vague terminology found in various welfare fund policies. This is provided to give examples and is not a comprehensive list, but features components pulled from several prison systems’ policies.

For a full accounting of prison “Inmate Welfare Fund” policies, see Appendix A above.

Revenue sources

- Commissary purchases and refund surcharges

- Phone system, kiosk, tablet, and vending machine revenue

- Hobbycraft sales

- Donations and gifts to institutions

- Interest earned on trust accounts

- Event income

- Contraband money

- Abandoned property

- Postage

- Photo ticket sales to visitors

- Recycling

- Performances of the “penitentiary band”

- Coin-operated lockers

Expenditures

- Recreation and sports equipment

- Literacy, hobby, vocational training, and educational programs

- Substance abuse treatment and self-help programs (e.g., Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous)

- Awards for academic, vocational, and sporting achievements

- Library books, movies, magazines, and other subscriptions

- Annual film licensing fees

- Stipends for referees and guest speakers

- Equipment to enhance the law library that is not otherwise required for legal access.

- Assistance with obtaining photo identification from the Department of Motor Vehicles.

- Nonprofit programming focused on individual responsibility and restorative justice principles

- Charitable donations

- Chapels and faith-based programs

- Purchase, rental, maintenance, or repair of bicycles for traveling to and from work-release program employment

- Environmental health upgrades to facilities

- Musical instruments

- Furniture

- Contract staff

- Contraband detection equipment

- Commissary operations

- Victims’ travel expenses

- Barber services

- Paralegal services

- Personal care items, postage, and phone call minutes for indigent people

- Commercial transportation and gate money for eligible people upon release

- Photocopier and other equipment rental

- Ice for housing units

- Compensation for property losses where the incarcerated person was not negligent

- Escort costs for funeral or sick bed visits for incarcerated people

- Special maintenance and capital outlay projects

- Loans to incarcerated people for notary services

Explicit prohibitions

- Revenue generated from vending machines not accessible to incarcerated individuals

- Candy/food

- Lobbying

- Refrigerators

- Banquets

- Alcohol

- Microwave ovens

- Catering

- Decorations

- Parties

- Coffee

- Congratulatory telegrams

- Gifts and flowers

- Promotional items

- Speakers fees

- Plaques

- Employee salaries

- Security equipment

- Automobiles

Vague terms and language

- Such as…

- Consist of but not limited to…

- Including but not limited to…

- Other nontax receipts

- Other miscellaneous incomes/revenues

- Other purposes

- Similar sources

- Other sources

- Money otherwise not allocated

- “Other goods and services for inmate benefits and needs”

- Uses “exclusively for the benefit of the inmates of the department”

- “[F]or the benefit of all inmates”

- “Or be for any goods or services determined by the Commissioner to be necessary to maintain and/or enhance the delivery of services to inmates.”

- Goods or services “that exceed those required for basic care and custody”

- “Any other purposes not covered by regular appropriations”

Appendix C — State statutes governing jail and prison “Inmate Welfare Funds”

State statutes governing jail and prison “Inmate Welfare Funds” [.pdf]

Footnotes

Estimates of total annual revenues for telecommunications, money transfers, and commissary purchases are hard to come by, but we estimate a low-end range of at least $2.7 billion to $3 billion per year. This figure notably does not include revenues from video calling and e-messaging, which are typically bundled with phone contracts and are thus difficult to disaggregate. To calculate our rough estimate, we added together $99 million in revenue from money transfers, $1 billion in phone revenues, $1.6 billion in commissary revenues, and $17.8 million in video revenues that we could ascertain from GTL and Pay Tel’s 2019 financial statements. Unfortunately, other vendors like Aventiv (which owns JPay and Securus) do not disaggregate video revenues from phone revenues. This gave us the $2.7 billion figure. The $3 billion figure comes from Worth Rises’ 2020 report The Prison Industry, which found annual revenues of around $1.4 billion for phones (excluding video calls and e-messaging) and $1.6 billion from commissaries. We opted not to include their figures for money transfers, which reflected market value rather than revenues. ↩

“Inmate Welfare Funds” go by many different names, such as Prisoner Benefit Funds, Institution Contingency Funds, The Trust Fund, Client Benefit Welfare Accounts, Resident Welfare Funds, Department Assistance Funds, Canteen Funds, and others. In some systems, they are not named at all but are described in laws and policies. While we do not condone the use of the term “inmate,” we are using it sparingly since “Inmate Welfare Fund” is the most common title in policies and available research. We use the term “welfare funds” elsewhere in the piece. Please note that in all cases we are specifically referring to funds for incarcerated people, not employees, as some prison systems have employee welfare funds as well. For more information on these funds in your state — including the name, revenue source, approved uses, and more — see Appendix A. ↩

Appendix B contains a sample list of specific revenue sources, expenditures, prohibitions, and vague terminology found in welfare fund policies. This list is not comprehensive and draws from policies used in several prison systems. For information on policies specific to each prison system, please see Appendix A. ↩

Oklahoma appears to have a combined welfare fund (or funds) for employees and incarcerated people, which are called the “Employee and Inmate Welfare Fund” and/or “Inmate and Employee Welfare and Canteen System Support Revolving Fund.” See Appendix A for more information. ↩

Please see Appendix A for a full accounting of prison system welfare fund policies. ↩

We could not locate welfare fund policies in two prison systems: Rhode Island and South Dakota. ↩

Individual trust accounts are essentially bank accounts for incarcerated people. When a person earns money from a job or receives deposits from loved ones, that money goes into their trust account. These accounts can accrue interest, though whether an incarcerated person can keep the interest depends on the laws and jurisprudence where they are incarcerated. ↩

Mississippi, for example, uses welfare funds to contribute to their “Discharged Offenders Revolving Fund,” which provides money to people leaving prison. See Appendix A for more information. ↩

Some prisons have policies regarding the provision of loans from welfare funds to incarcerated people. Michigan, for example, allows welfare funds to facilitate loans to help incarcerated people pay for notary services, while Vermont prison policy allows for the establishment of a lending fund that uses welfare fund proceeds to help people obtain housing after release. Washington State, on the other hand, explicitly bans the lending of welfare fund dollars. See Appendix A for more details. ↩

In their excellent 2015 article Taxing the Poor: Incarceration, Poverty Governance, and the Seizure of Family Resources, Mary Fainsod Katzenstein and Maureen R. Waller describe this practice as “an invisible system of revenue and taxation that exploits the ties of family dependency.” The article goes on to quote a parent of an incarcerated person in Washington, who notes that they pay taxes on the funds they deposit into their son’s trust account, which are then subject to a 35% deduction. John Koster, a Washington State representative who introduced a bill to end these garnishments (which died in committee), astutely described this practice as “double taxation.” Katzenstein and Waller end the article by asking whether this constitutes “a system of welfare socialism for the better-off that is dependent on the predation by the state of the poor.” ↩

In some cases, policies specifically authorize the use of welfare funds for certain essential expenses, such as building construction or maintenance. Whether authorized by law or policy or simply through omission, we argue that the use of funds meant for the general welfare of incarcerated people in this manner is unethical and exploitative. Departments have general budgets that are appropriated by a public legislative process to fund their operations. They should under no circumstances be extracting dollars from people impacted by incarceration to run their facilities. ↩

In addition to reading prison policies, financial audits, legislative testimony, and news reports, our research for this report included gathering perspectives from a small group of incarcerated people and advocates via informal conversations. While this was by no means a robust survey, our conversations did yield some insight into awareness of and opinions on welfare funds. ↩

In 2021, for example, Olland Reese testified to the Maine state legislature about the value of welfare funds in promoting mental health, pointing to their use in paying program facilitators and purchasing stress relief items like equipment for fitness and organized sports, board and card games, items for the music program, and more. This testimony was accompanied by the signatures of “over half the prison population” at Maine State Prison. ↩

Somewhat alarmingly, when we requested access to fiscal policies governing North Carolina’s “Correction Inmate Welfare Fund” (also known as the “Central Welfare Fund”), we were told by the department that there were “currently no fiscal policies in place for the North Carolina prison system.” An official said that “the prison system’s [fiscal policy section on the website] has some old policies from more than a decade ago, when the agency was known as the Department of Correction,” that they are “working on updating them for consideration/approval by leadership,” and that “those old policies have not been in place for several years.” For these reasons, we were unable to obtain accurate up-to-date welfare fund policies for North Carolina’s prison system. ↩

In Pennsylvania, for example, the committee that oversees the fund must give approval to the following requests:

- Concrete pads or similar over $5,000

- Maintenance or upgrades over $5,000

- Buildings/sheds for incarcerated peoples’ activities/equipment

- Education software

- Computers, printers, WIFI

- Permanent fixtures

- Staff overtime for all staff

See Appendix A for more information. ↩

Read our blog post and visit PrisonOversight.org for detailed information on the state of oversight and accountability in U.S. corrections, including prison oversight profiles for each state, information on reform efforts, news, and legislative updates. ↩

As scholars Mary Fainsod Katzenstein, Nolan Bennet, and Jacob Swanson write, “Few sheriff and prison administrators may be buying beach houses, but corporate commissions/kickbacks are financing their occupational livelihoods. Jails, prisons, and even general county operations are subsidized with monies levied on services provided to the incarcerated population and paid for by incarcerated men, women, and their families.” ↩

To be more precise, we calculate that $19,971.35 is approximately the median annual income prior to incarceration for people in 2024. This is an adjusted figure from our report Detaining the Poor using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI Inflation Calculator. That report found that people in jail had a median annual income of $15,109 in 2015 dollars prior to their incarceration — less than half (48%) of the median for non-incarcerated people of similar ages. ↩

Appendix C may be useful to those wishing to investigate welfare funds in local jails because it contains legal language that, in some states, pertains to sheriffs and county facilities. The document also has notes on revenues for certain states in the “Notes” column. ↩

Scholars Mary Fainsod Katzenstein, Nolan Bennett, and Jacob Swanson describe this use of vague language as a “legal heist” that conceals many of the unaccountable uses of these funds. ↩

In this case, welfare fund money from people detained at the jail was actually used to purchase items for an entirely separate county department. ↩

In this case, the county was trying to use welfare funds generated from incarcerated people’s families toward the 10% cash-match required to receive $40 million in state financing for a new jail. ↩

The KnockLA article continues with more context for the sheriff’s arguments: “This is a common pattern. LASD recently decried staff shortages in spite of the fact that it hired or promoted 1,900 new employees under the county’s “hiring freeze.” The sheriff’s 2022-23 allocation from the county exceeds that of Public Health and the Fire Department by over a billion dollars each. LASD expressed that an increase in appropriations from $3.4 to $3.6 billion is evidence of ‘defunding.’” ↩

Though this report focuses on prison systems, this example from Minnesota pertains to a civil commitment facility operated by the Department of Human Services. ↩

Welfare fund revenues peaked at $4.4 million in 2013. ↩

For example, if incarcerated workers build furniture that the department sells to the public for a profit, all (or at least some) of those profits should return to the welfare fund for collective use while also providing a fair wage to incarcerated workers. ↩

Interest earned on individual trust accounts sometimes goes into these funds, but who owns this money is a hotly contested issue. At the most basic level, that money should belong to the account holder and could be used to aid in reentry — especially given the meager wages of incarcerated labor. ↩

See Appendix A for more information. ↩

Events

- April 15-17, 2025:

Sarah Staudt, our Director of Policy and Advocacy, will be attending the MacArthur Safety and Justice Challenge Network Meeting from April 15-17 in Chicago. Drop her a line if you’d like to meet up!

Not near you?

Invite us to your city, college or organization.