New data: State prisons are increasingly deadly places

New data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that state prisons are seeing alarming rises in suicide, homicide, and drug and alcohol-related deaths.

by Leah Wang and Wendy Sawyer, June 8, 2021

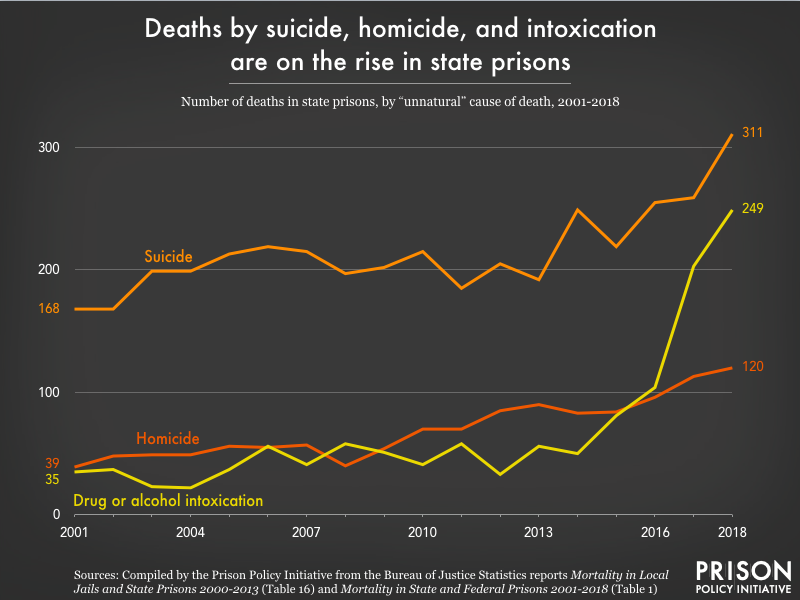

The latest data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) on mortality in state and federal prisons is a reminder that prisons are in fact “death-making institutions,” in the words of activist Mariame Kaba. The new data is from 2018, not 2020, thanks to ongoing delays in publication, and while it would be nice to see how COVID-19 may have impacted deaths (beyond the obvious), the report indicates that prisons are becoming increasingly dangerous – a finding that should not be ignored. The new numbers show some of the same trends we’ve seen before – that thousands die in custody, largely from a major or unnamed illness – but also reveal that an increasing share of deaths are from discrete unnatural causes, like suicide, homicide, and drug and alcohol intoxication.

State prisons, intended for people sentenced to at least one year, are supposed to be set up for long-term custody, with ongoing programming, treatment and education. According to one formerly incarcerated person, “if you have the choice between jail and prison, prison is usually a much better place to be.”

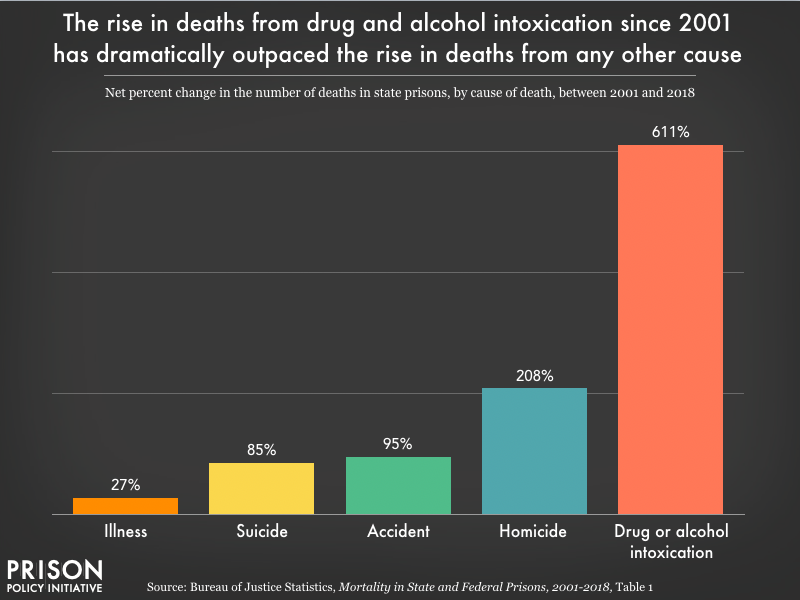

Deaths in jail receive considerable attention in popular news, and here on our website – which they should, given the deplorable conditions that lead to tragedy among primarily unconvicted people. State prisons, on the other hand, are regarded as more stable places, where life is slightly more predictable for already-sentenced people. Why, then, are suicides up 22 percent from the previous mortality report, just two years prior? Why are deaths by drug and alcohol intoxication up a staggering 139 percent from the previous mortality report, just two years prior?

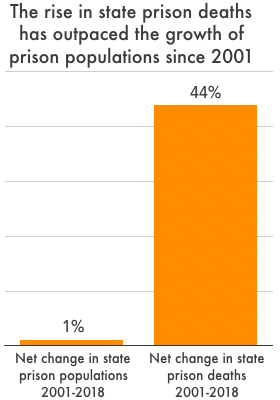

The answer isn’t just because there are more incarcerated people. The very slight net change in the state prison population since 2001 pales in comparison to the increase in overall deaths occurring in these facilities. (Prison populations have actually decreased since peaking in 2009, but they’re still larger in 2018 compared to 2001.) Prisons have been, and continue to be, dangerous places, exposing incarcerated people to unbearable physical and mental conditions. State prison systems must greatly improve medical and mental healthcare, address the relationship between correctional officers and the health of their populations, and work with parole boards to accelerate release processes. Then, maybe, a state prison sentence would not become a death sentence for so many.

Record-setting deaths in almost all categories

In 2018, state prisons reported 4,135 deaths (not including the 25 people executed in state prisons); this is the highest number on record since BJS began collecting mortality data in 2001. Between 2016 and 2018, the prison mortality rate jumped from 303 to a record 344 per 100,000 people, a shameful superlative. It may seem like a foregone conclusion that more people, serving decades or lifetimes, will die in prison. But for at least 935 people, a sentence for a nonviolent property, drug, or public order offense became a death sentence in 2018.1

BJS slices mortality data in many ways, one of which is “natural” versus “unnatural” death; “natural” deaths are those attributed to illness, while “unnatural” deaths are those caused by suicide, homicide, accident, and drug or alcohol intoxication. Any death pending investigation or otherwise missing a distinct cause gets filed away as “other,” or “missing/unknown.” Other than accident deaths, every cause of death had its worst year yet in 2018.

Taking BJS’ definitions of “natural” and “unnatural” deaths at face value2, the data shows that, like in past years, most (77%) of all prison deaths in 2018 were “natural.” However, “unnatural” or preventable deaths make up an increasing share of overall mortality: In 2018, more than 1 in 6 state prison deaths (17%) were “unnatural,” compared to less than 1 in 10 (9%) in 2001.3 Clearly, prisons are doing poorly at keeping people in their care safe. We must remember that being locked up is the punishment itself; inhumane conditions are not supposed to be part of a prison sentence.

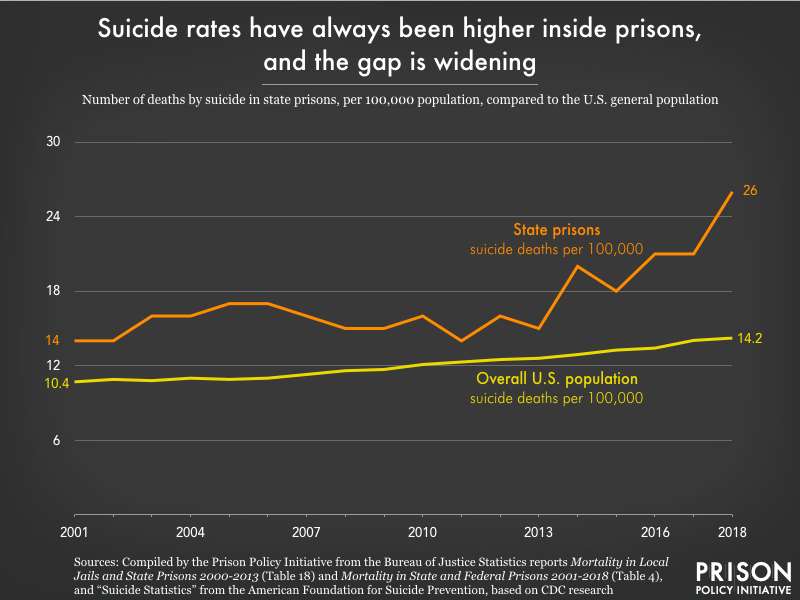

Suicide rates in prison are higher than ever

Incarceration is not only difficult for someone who comes in with mental health needs, but it creates and exacerbates disconnection, despair, and overall psychological distress. Prison is basically a mental health crisis in and of itself, and too many incarcerated people contemplate and/or complete suicide.

In 2018, state prisons saw the highest number of suicides (340) since BJS began collecting this data 20 years ago. Compared to the 1% net growth of state prison populations since 2001, suicides have increased by a shocking 85 percent. Suicide is an affliction for the general U.S. population, but the mortality rate from suicide in state prisons has always been higher.

The BJS data does not allow us to compare death rates by sentence length, but it’s hard to ignore the possibility that longer sentences are contributing to a sense of hopelessness and forcing incarcerated people into harmful situations. Other data collected by BJS shows that between 2001 and 2015, the number of people admitted annually to state prison with a sentence of 5 years or longer grew by nearly 12,000 people, accounting for almost all of the growth in new prison admissions over that time period.4

At the end of 2015, 1 in 6 people in state prisons had already served over 10 years. To add insult to injury, between 2016 and 2018, the average state prison sentence grew by about four months.

Not only does a longer incarceration increase the sheer probability of having a mental health crisis inside, but it also creates the conditions for this to happen. With longer periods of separation from loved ones, and a rapidly changing outside world, people serving long sentences are isolated and deprived of purpose.

When someone in prison is clearly in crisis, correctional officers are supposed to act swiftly to prevent suicide and self-harm. Not only do officers routinely fail to recognize mental health warning signs, but they’ve been found allowing and even encouraging self-harm, a disturbing reality. And on an institutional level, prison systems avoid making the necessary changes to protect people in dangerous conditions: In response to a Department of Justice investigation finding that the Massachusetts Department of Correction “exposes [people experiencing a mental health crisis] to conditions that harm them,” the DOC is piloting Fitbit-like bracelets for its population to track changes in vital signs related to mental health distress. Instead of rolling back harsh solitary confinement practices and improving how correctional officers respond to crises, the DOC is increasing surveillance and allowing another private company to profit off of prisons.

Who is committing homicide in prison?

The number of homicides in state prisons reached a record high of 120 deaths in 2018, a reminder that while prisons are secure, they are largely unsafe. Violence in prison is commonplace, tied to trauma prior to incarceration as well as mental health stressors inside. The rate of homicide in state prison is 2.5 times greater than in the U.S. population when adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

The age of those who died in prison seems most relevant when talking about illness, but older people were actually more at risk of homicide and all other causes of death, except for accidents. By absolute numbers, more homicide deaths affected people in their 20s, 30s and 40s, but the homicide rate was highest for incarcerated people aged 55 and older. They were twice as likely to die by homicide as anyone aged 25 to 44.

What about who is actually behind the deaths that are ruled homicides? The BJS data does not separate homicide committed by incarcerated people from death “incidental to the use of force by staff,” or even “resulting from injuries sustained prior to incarceration.” While correctional officials might go right to “prison gangs” or otherwise blame incarcerated people for these deaths, it’s a bit more complicated than that. In this terrible instance, a correctional officer heeded a request to close a cell door remotely, allowing someone to fatally wound a 72-year-old man in total privacy. The nuance of who is responsible for prison homicides points to huge gaps in security and staffing, but also a clear indifference to people’s lives and unaddressed anger and trauma.

How can drug and alcohol intoxication deaths be so high, when prison security is so strict?

As we look back to the beginning of mortality data collection in 2001, no manner of death has spiked more than drug overdoses and alcohol intoxications. (Unfortunately, the BJS data does not distinguish between the two.)

With such coarse data, it’s difficult to pinpoint an explanation for this trend with certainty. However, no conversation about illicit substances inside prisons would be complete without mention of contraband, particularly drugs brought in by correctional staff.

In the name of preventing contraband from entering prisons, many state prison systems have cracked down on incoming mail and visitation, two major lifelines for incarcerated people. However, there’s evidence to suggest that the majority of drugs, as well as sought-after items like cell phones and cigarettes, are brought in directly by prison staff. In 2018, we conducted a survey of local news coverage that revealed a dozen instances in that year alone where staff were fired, arrested, or sentenced with smuggling drugs and other items into correctional facilities.

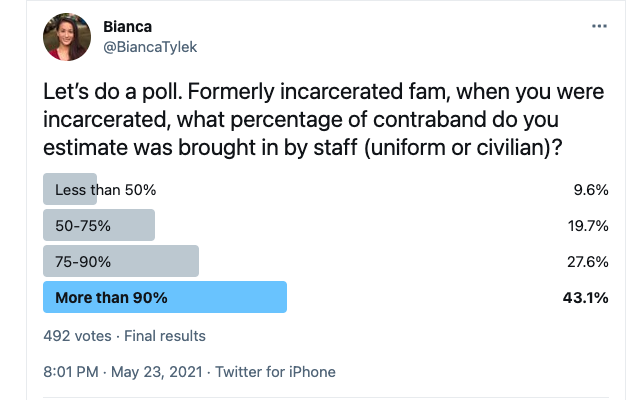

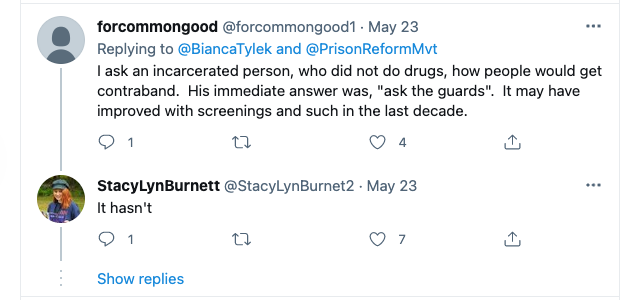

A recent Twitter poll doubles down on the premise that prison security staff are the major players in contraband movement. Initiated by Worth Rises director Bianca Tylek, the poll and resulting thread brought formerly incarcerated voices into what could be the most revealing look to date at how correctional officers in particular are wound up in contraband dealings.

With so many people in state prisons lacking proper treatment for substance use disorders, it’s no wonder corrections staff will use their access to the outside and charge exorbitantly for drugs like Suboxone or potent synthetic cannabinoids. Instead of improving the quality of healthcare and treatment for drug addiction, prisons are imposing costly restrictions on mail and visitation and incentivizing their own staff to carry out illegal activity.

Mortality data for 2020 won’t be released for another two years or so, but we don’t have to wait to see whether drug contraband was drastically reduced when state prisons banned in-person visitation due to the pandemic: it wasn’t. In Virginia, for example, the Department of Corrections found that drugs did not become more scarce; positive drug tests actually increased after pandemic restrictions went into effect. Texas prisons also saw an uptick in drug contraband and related disciplinary reports in 2020, even as prison populations declined and visits were limited or cut off entirely.

Can we relate the thriving drug market in prisons to increasing drug-related deaths? Not directly. Clearly, though, the people working in prisons, who already turn a blind eye to violence and suffering, are responsible for introducing some of the dangerous substances that killed 249 people in 2018.

Illness is still the most common cause of death, but how natural is illness in prison?

Even though most prison deaths each year are attributed to illness, and are therefore “natural,” being sick or old in prison is not quite what it is on the outside. Incarceration can add 10 or 15 years to someone’s physiology, and take two years off of their life expectancy per year served, alarming statistics when considered alongside longer sentences and high costs of healthcare for older people.

The systemic neglect of illness and aging in prison populations isn’t natural at all. Every summer, we hear about prisons in hot climates that lack air conditioning, exposing incarcerated people to consistent temperatures of over 100 degrees. We’ve previously reported on these extreme heat conditions that exacerbate chronic diseases, counteract medications, and increase the risk of dehydration and heat stroke among even the healthiest people. In Texas, for example, when summer incarceration is described as unconstitutional, deadly, and a practice in reckless indifference, how natural are some deaths due to “illness”?

Again, consider the mortality data that will eventually come out for 2020, when prisons and jails played host to the COVID-19 pandemic and over 2,600 incarcerated people (and over 200 staff) died as a result. We know how badly every state handled this situation; it will be important not to brush these deaths aside as simply succumbing to illness – nor the deaths caused by other illnesses that went untreated in understaffed, overwhelmed prison health systems. These thousands of people were failed by state criminal justice systems, and deserved care and precaution while in custody.

State criminal justice systems can improve prison healthcare and loosen their grip on parole processes

We are supposed to trust prison systems to keep people alive and safe, so they can serve their sentences and be released back to their communities. The significant increase in overall “unnatural” deaths, like suicide, homicide, and drug intoxication tells us that state prisons are failing to provide humane conditions for incarcerated people, and it’s killing them. There are many ways that state prisons and related agencies can reduce the risk of death.

- A surefire way to reduce risk is to reduce prison populations, and parole boards are a natural bottleneck to this end. Parole hearings and approval rates must increase in order to move large numbers of incarcerated people back into their communities, despite many states failing to do this in 2020 when it was clearly a matter of life and death. Compassionate release should be ramped up, and no one should be ordered to return to prison after recovering from illness. Burdensome in-person check-ins should also be eliminated to reduce the incidence of low-level technical violations of parole and probation.

- States can also consider major sentencing policy changes to address the scourge of long prison sentences that only worsen physical health, mental health, and preparation for reentry. Dozens of state legislatures are considering “second-look” policies to review cases for those currently serving excessive, costly sentences.

- As one of the most basic services guaranteed to people in custody, healthcare must be improved. And if it feels like prison healthcare spending is already outrageous, releasing people – especially older, sicker people – would certainly mitigate those costs. Medical care aside, correctional officers must respond swiftly to sick calls and emergencies.

- Providing high-quality treatment for substance use disorders would prevent incarcerated people from turning to desperate and dangerous solutions. State correctional agencies must acknowledge the scale of drug smuggling facilitated by correctional staff. Instead of banning in-person visitation and meaningful resources like books, prison staff should be subject to stricter security measures and enduring consequences.

- Improving prison conditions can also prevent many “natural” deaths in prison; for example, there should be universal standards for indoor temperatures where extreme heat can be deadly. In a decently climate-controlled space, medications will work as intended, and people can remain focused on education, employment, and connection with loved ones, and deadly viruses might not spread so easily. And as we have learned through the pandemic, improving ventilation, access to healthcare, coordination with public health departments, and reducing population density by releasing more people from prison can prevent countless deaths when infectious diseases enter prisons.

Under pressure, change does happen, and we have been tracking state-level changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Some changes were only temporary or did not go far enough to slow the spread of the deadly virus. Had states taken these actions years ago to reduce other dangers in prisons, we might not have seen record mortality in 2018 – or for that matter, in 2020.

Footnotes

-

This calculation, based on Table 4 in Time Served in State Prisons, 2018, excludes state prison deaths among people convicted of any violent offense, many of whom may also have been serving relatively short sentences. Also, this data set is not perfectly consistent with the Mortality data set; data in the Time Served report was not available from 8 states and D.C. ↩

-

It’s reasonable to be skeptical of the natural/unnatural distinction put forth by BJS: Missing/unknown deaths happen to be up almost 700% from 2016, but are conveniently left out of this binary. ↩

-

Federal prison deaths (including private facilities) were only reported as an aggregate count until 2015, with limited details about cause of death. In 2015, “unnatural” deaths made up 11% of federal prison deaths. In 2018, they accounted for just over 14% of all federal prison deaths. ↩

-

According to data from the National Corrections Reporting Program, 127,060 people (36% of all new court commitments) were admitted to state prisons in 2001 with a new sentence of 5 years or longer. In 2015, that number had grown to 138,975 (38% of all new court commitments), an increase of 11,915 admissions. Over the same time period, the total number of new court commitments to state prisons – of any sentence length – grew by 12,029. ↩